Aubers Ridge 9 May 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Aubers Ridge 9 May 1915

At the end of April 1915 the Sussex Express carried a cheering report from one of its former reporters, Private W G Horton of the 5th Royal Sussex. Seated on a straw bale in “glorious sunshine” at a rest billet 10 miles from the Front, he expressed the optimism of Lewes’s territorials on a beautiful spring day, that the war would soon be over and they could return home to their families and loved ones.

Sent to guard the Tower of London on the outbreak of war and to undertake further training there, 60 volunteers of D (Lewes) Company 5th (Cinque Ports) Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, led by their company commander, Captain Thorold Stewart-Jones aof Southover Grange, had left Lewes for the Front after a 48 hours home leave and a rousing send-off by the Mayor and townspeople on 14th February 1915. Up to then, the war had claimed relatively few Lewes men’s lives, which totalled 21 to the end of 1914 and a further seven by the end of April 1915.

The worst day had been 14th September 1914 when five Lewes men had been killed on the River Aisne, during the ferocious fighting to halt the seemingly inexorable German advance on Paris. These men were professional soldiers, so some losses might well have been expected. But the men of the 5th Royal Sussex were territorials, weekend soldiers with everyday civilian jobs, involved in the everyday life of the town, who, apart from a fortnight’s annual summer camp, went home to their families each night – until the war changed all that.

Formed in 1908, the whole battalion was made up of local volunteers, divided into eight companies, each one based in an East Sussex town. Originally formed as local defence forces, territorial battalions drew upon local loyalties and a sense of local patriotism to protect the country in the face of any attack. Overseas service, for which these men willingly volunteered, was not the aim when these units were formed. But in August 1914, everything had changed.

On 18th February the 5th Battalion left the Tower of London, entrained for Southampton and sailed overnight on the SS Pancras for Le Havre, where they embarked the following afternoon. By the end of March they were in position on the front line at Richebourg l’Avoué, 10km west of Lille, where they remained until they found themselves in support trenches on the evening of 8th May 1915, with orders to attack at dawn.

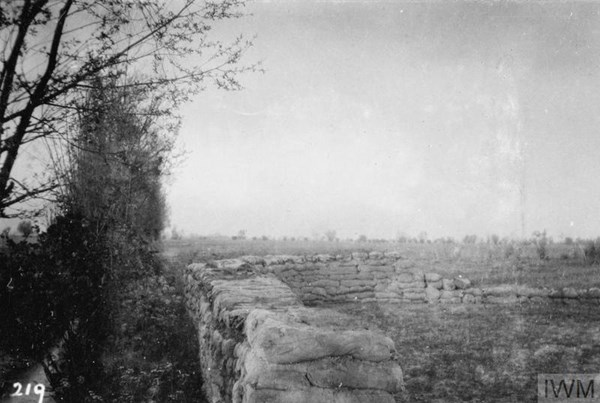

Planned as part of a joint Anglo-French assault on German lines, the attack on Aubers Ridge was an unmitigated disaster – across several hundred yards of flat, poorly drained, open ground, criss-crossed by numerous drainage ditches in front of recently reinforced German trenches on higher ground, protected by barbed wire and flanking machine gun fire.

The British plan was for a heavy artillery barrage to destroy or at least severely weaken German defences immediately before the infantry attack, but inadequate supplies of ammunition and too few guns meant that the damage caused to the German lines was minimal while alerting German forces to the imminent attack.

The bombardment began at 5.00am and intensified at 5.30am with orders to begin the attack at 5.40am. In the first wave was the 2nd Royal Sussex, flanked by the Royal Munster Fusiliers on their left and the 1st Northamptonshires on their right. The 5th Royal Sussex was to follow on immediately behind, with the Lewes men now part of C Company, in the front.

In the initial advance towards the British advanced trench, C Company met intense rifle and machine gun fire and lost at least 30 men killed or wounded. Worse was to follow as wave after wave of men were cut down as they advanced across the open ground or were shot as they came up against the barbed wire. By 7am the position was recognised as hopeless and the order to retire was given. From an initial strength of 850 fighting men, Lt Col Langham, their commanding officer, estimated only 360 effective rifles were left and two of the surviving captains were sent to hospital with nervous breakdowns.

As news of the disaster began to reach home in the days that followed, the Sussex Express carried a series of graphic letters from survivors, describing their experiences. An officer of the 2nd Battalion wrote:

'After a bombardment of our own guns on the German trenches, the good old Sussex went forward like one man, only to be met by a fire … which simply mowed us down like rabbits… The barbed wire in front of the German trenches was not cut by our shrapnel as planned, and we were caught like rats in a trap.'

Another officer wrote:

'Stewart-Jones devoted all his efforts, sparing himself neither time nor trouble to make his company efficient and he succeeded beyond all expectations… It was a fine thing to have nursed that company as he did, and leading them into action, fall at their head right against the German trenches… When he reached the front trench… seeing gaps in the assaulting line… he dashed on with great gallantry and overtook the 2nd Sussex line, and with them advanced in short rushes. Stewart-Jones and a few others got to the German wire – no-one at all got any further.'

Private George Maslen, just 17, of Westgate Street, described what he saw:

'It was about twenty minutes to five in the morning when our guns started to play havoc with the German lines. Our shells knocked their trenches to blazes, sending sandbags, dirt and wreckage sky high… All along the lines was a yellow and greenish haze, and it seemed as if nothing could live… When we got the order to charge, the 2nd, whom we were supporting, went over the top like we do on bonfire day. We followed, and got three parts over ‘no man’s ground’, when they opened a terrible fire with machine guns, and we lost heavily.

More men kept coming out to assist us, but it was no use and we had to lay there. It seemed terrible… not being able to raise your head, and your mates being knocked over and needing your help, and you could not move. One chap got hit and I handed him my water bottle, and a bullet whizzed by my ear, hitting my haversack. There were shells dropping behind us, and deadly machine gun fire in front of us… I laid out there for two hours, and then…by short crawls on my belly I managed to get to our barbed wire, and I laid there a few minutes.

I then crept through the wire, until I came to the parapet and then I thought ‘neck or nothing’ so I bolted over, and just as I got to the top a bullet hit my putty, going right through putty, sock and pants, and just left a mark on my legs. But I got in safely… After I got over it and got my breath, I helped get the wounded in and bandage them up… Not another band of fellows could have trod it better than the Sussex Regiment did. We were relieved the same night, and when roll call came it seemed awful.'

Of the 60 Lewes men who had been cheered on to the evening train to London on 14th February, 14 were killed outright and two more died of their wounds within a few days. Many more were wounded, a poignant reminder being an inscription on a grave in St John sub Castro churchyard recording the death of Private William Charles Reynolds 5th Royal Sussex Regiment who died on 8th October 1918, of wounds received on 9th May 1915. The disastrous attack at Richebourg saw the largest loss of life in any military action which Lewes has ever suffered.

The shock felt in Lewes as news of the circumstances and scale of losses on 9th May 1915 gradually filtered back to the town was such that the events were still remembered and talked about in Lewes when I was growing up in the 1950s and 60s. The town was completely unprepared – as the Sussex Express commented on 14th May:

'Up until Sunday last the men from Lewes district had been distinctly fortunate and, although having hairsbreadth escapes, their casualties were very light…'

What undoubtedly made it worse for many anxious families was the initial lack of firm news about their particular loved ones.

When that edition went to press little was known except that the Lewes men of the Royal Sussex had taken part in an advance against German trenches and that there were heavy casualties. A handful of postcards and telegrams from the wounded and survivors sought to reassure their families that they were, at least, alive. Amongst these, Private W G Horton, a former Sussex Express reporter sent a telegram, just after landing in England two days after the attack, stating: “Just landed Dover. Lost left thumb. Got smack in forehead and two black eyes. Don’t worry. Quite cheerful. Going up to Manchester soon.”

But apart from confirmation from his brother Stewart, who was wounded, that Clifford Andrew of Ringmer, an ex-Grammar School boy and prominent Lewes Methodist, had been killed, and that Captain Thorold Stewart-Jones had been wounded and was missing, there was little concrete to report.

The following Friday, 21st May 1915 the Lewes page of the Sussex Express carried the headline 'Covered with Glory. Memorable Charge of the 5th Sussex. Territorials killed and wounded' while the back page carried photographs of 11 of the wounded and two dead, as well as an annotated group photograph of the officers of the 5th Battalion, noting those wounded, missing or dead, but reported that many Lewes families were still waiting for news. The article itself contained graphic descriptions from the letters of survivors while conveying the news of six Lewes men confirmed dead and five others listed among the wounded, all of whom were subsequently confirmed to have lost their lives.

Altogether 16 Lewes men of the 5th Royal Sussex and one man from the 2nd battalion died on 9th May 1915 or subsequently, of their wounds.

At least as many again of the Lewes contingent were also wounded but not fatally. Of the 60 men who left Lewes for the Front on 14th February, more than half either died or were seriously wounded at Aubers Ridge.

These men came from a variety of backgrounds and occupations. Captain Stewart-Jones aged 41 was a barrister of the Inner Temple, who had come to Lewes in 1908 when his mother bought Southover Grange. A former head boy of Haileybury College before going on to Trinity College, Cambridge, he was a churchwarden at Southover and a governor of Lewes Exhibition Fund and had been commanding officer of the Lewes Company 5th Royal Sussex since 1912. He was also active in the Scout movement, the local Red Cross and Lewes Swimming Club. He left a wife, two girls and three boys, the youngest, Michael, born posthumously in July 1915.

Private Lee Haydon aged 28 and Corporal Alfred (Tubby) Langridge 34, were both Lewes Grammar School boys. Haydon worked as a clerk at the Old Bank, Lewes and was secretary of the Lewes and District Cricket League. His father was a chartered accountant in London. Like Tubby Langridge, he was a member of the recently formed Lewes Operatic Society, as well as playing football for Lewes Football Club. Langridge, of Prince Edwards Road, was a land surveyor, a keen member of Lewes Cyclists Club, a member of St Anne’s church choir and St Michael’s Social Club.

Also a former member of St Anne’s choir was Lance-Corporal George Ernest Peel aged 24, whose father was a sidesman at Southover Church and ran W H Smith’s bookstall at Lewes Station until his promotion as manager of the shop at London Bridge in 1910. Peel was employed as a clerk in the County Education office, was an active Oddfellow and Druid, a member of Southover Church Social Club and the local Red Cross. A keen sportsman, he played for Wellington Rovers, a local team, and topped the batting averages for the 1914 season at Lewes Priory Cricket Club, where he had been due to receive the prize winner’s bat, which, because of his death, was subsequently inscribed and presented to his father.

Another keen footballer was Private Herbert George Funnell aged 19, of Wellington Street, who played for Lewes Wednesday Football Club and had only recently joined the Lewes Company 5th Royal Sussex as a bugler/drummer when war broke out while he was on his first summer camp. Also 19 was Private Harold H Bleach, a bottler at the Southdown and East Grinstead Brewery in Malling Street. He lived with his mother in Daveys Lane and had gone to South Malling School. Private Henry William Lancaster aged 20, of Sun Street, was another bugler. He worked for the Pearl Assurance Company and went to the Wesleyan Chapel. His father was a Lewes Police Constable.

Another insurance agent, in this case for the Royal London Insurance Office in Lewes was Private Edgar Rigelsford aged 23, who grew up in Hailsham, where his parents lived. He enlisted in the Lewes Company in September 1914, having previously served five years as a territorial at Hailsham. It was not until July 1915 that his death was confirmed. According to QMS H Roberts, his former teacher at Hailsham School and an eye witness: “he sacrificed himself for his comrades, going over the breastworks three times under howitzer, shrapnel, maxim gun and rifle fire, to fetch in the wounded. Had he returned, he would have been recommended by Captain (now Major) Courthope for honours … I can assure you no efforts of mine will be spared in trying to obtain them…”

Private Arthur Blagrove aged 24, a tailor’s cutter and former Southover choirboy, was the son of Edwin Blagrove a local jeweller and watchmaker of 72 High Street.

Private Herbert V Mann aged 20 who lived with his grandmother in Thomas Street was employed as a gentleman’s servant having previously been a messenger boy at the County Club. His father, the proprietor of Messrs W Mann & Co, Lansdown Place dyers and cleaners of carpets, curtains etc had died in 1907. He was a former Central School boy like Private Arthur Moore aged 19, of Wellingham Cottages, commemorated on the memorial window in South Malling Church. It was Moore’s friend, 17 year old Private Arthur Maslen of Westgate Street, quoted last week, who first reported him missing, fearing for the worst. All these men are commemorated on the memorial to the missing at Le Touret.

Private John Thorpe junior aged 19, also a bugler/drummer, was similarly commemorated at South Malling. He lived with his parents at 101 South Street. Shot through the shoulder with a leg missing and his head swathed in bandages, he had been visited by his parents in hospital at Chatham, the day before he died on 17th May, eight days after he was wounded. He worked at the Lewes Gas Works and was a keen member of Cliffe Bonfire Society whose members laid a wreath on his grave on the day he was buried. Amongst the other floral tributes was one “from his ever-loving sweetheart Mabel.”

Two other men of the Lewes Company died at Casualty Clearing Stations in the aftermath of the battle. Private George Edward Johnson aged 19 of Castle Banks, a former Post Office telegraph boy and later employee of Messrs Wightman and Palmer, died at the 33rd CCS at Bethune, where he is buried. His father was a former regular soldier of the 1st Royal Sussex, present at the relief of Khartoum. Private William G Arnold aged 28 of 33 North Street, 2nd Royal Sussex was a reservist called up at the outbreak of war. He had been in France since 12th August 1914 and had previously received a bullet in the arm in January. He died of his wounds on 12th May at Lillers, a major hospital centre, and was buried there.

Finally William Charles Reynolds of 7 Phoenix Cottages, an iron moulder at Everys works, had enlisted in the Lewes Company in May 1913 when he was 17 years and 9 months old. Wounded on 9th May by a shrapnel bullet in the spine, he developed acute tuberculosis, aggravated by a weak heart and was discharged home in November 1915, dying from the effects of his wounds on 8th October 1918. Other men returned home to live with their disabilities, carrying the awful memories of 9th May 1915 with them for the rest of their lives.

Article by Dr Graham Mayhew

Sources: The Sussex (Agricultural) Express