Away from the Front Line – Poperinge, La Poupée and Talbot House

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Away from the Front Line – Poperinge, La Poupée and Talbot House

The 50th anniversary of the death of Tubby Clayton

In his memoir, ‘Tales of Talbot House’ (see references below) Tubby Clayton* described Poperinge, at the beginning of the war, as a town of 11,000 inhabitants ‘with no features of interest to the visitor’ (page 8). It was 12 km directly to the west of Ypres and relatively, but not entirely, safe because of its distance from German artillery.

From the second half of 1915 Poperinge served as a kind of garrison town for British troops. Thousands of troops poured into and through Poperinge to head for Ypres and the front line. At times ‘the population of the town rose to a quarter of a million’ (TTH p8). British soldiers were only paid 1 shilling (5p) per day – but they had nothing to spend their money on in the trenches. When they got their accumulated pay they spent it freely in Poperinge.

Local shops did a roaring trade and clubs and ‘estaminets’ (cafés) of ‘good, bad and of all intermediate complexions’. (TTH p12) mushroomed all over the town. To many soldiers seeking relief from the squalor, boredom and occasional terror of the front line Poperinge was ‘the Eighth Wonder of the World’.

There were clubs, cafés and hotels for ‘Officers Only’ such as Cyrille’s, Skindles and A la Poupée. And many more, smaller, establishments that catered for the ‘Other Ranks’. The soldiers’ favourite food was ‘oofs et freets’ (oeufs et frites) – egg and chips. Better still: ‘dooble oofs et freets’! There were several theatres in town and even cinemas, the then state-of-the-art entertainment, which featured silent B&W films including those starring Charlie Chaplin (British, born in London but an immigrant to the USA).

There were also abundant supplies of alcohol in various forms – though drunkenness was severely punished. The British soldiers did not like Belgian beer which they swore was diluted with water drawn from the many ditches and small rivers that surrounded Poperinge. This was untrue. Belgian beer was brewed in a different way to the beer the soldiers were used to at home – it was a lager-type beer seldom drunk in the UK at that time. (TTH p10)

There were houses in the Poperinge where some of the soldiers’ other needs were catered for. The night-working ‘professional ladies’ they patronised had to be free of VD. (In the 'In Flanders Fields’ Museum in Ypres there is an example of a medical certificate issued by a doctor that his female patient was 'clean’). While prostitution was allowed (red light at the front door for other ranks; blue light for officers) gambling was not and often the Military Police, would raid places where they suspected gambling took place. Punishments were severe.

There were more clubs encouraged by the army that might keep soldiers away from the temptations of the town: the YMCA, the Church Army club and, of course, Tubby Clayton's famous Talbot House (Toc H) (the so-called 'Every Man's Club').

There was strictly enforced segregation of ranks in Poperinge – except at Toc H. Some of the clubs were 'Officers Only' and so were out of bounds for most soldiers - the ‘Other Ranks’.

La Poupée

One such famous ‘Officers Only’ café was 'La Poupée' (The Doll) in Market Square where the Cossey family lived. What was to become a prime attraction for off-duty officers had started as a simple shop. Father, Elie Cossey was a shoemaker by trade while his wife kept a lingerie and haberdashery shop at the same address. (As a sideline, it is claimed, she made dolls. A large doll, a mannequin dressed in Mde. Cossey’s finest, may have stood in the shop window – hence the name of the café.) M. Cossey was a quick-witted and resourceful businessman and he quickly saw great opportunities in the arrival of thousands of troops. He turned the shop into a café and bought an automated piano, a ‘Pianola’, to entertain his customers. The café was strictly ‘Officers Only’. Officers were much better paid than the men they commanded – for example infantry Captains got 12s 6d (62.5p) per day (more than twelve times the pay of a private soldier) - and bottles of champagne and good wine were readily available to them at La Poupée.

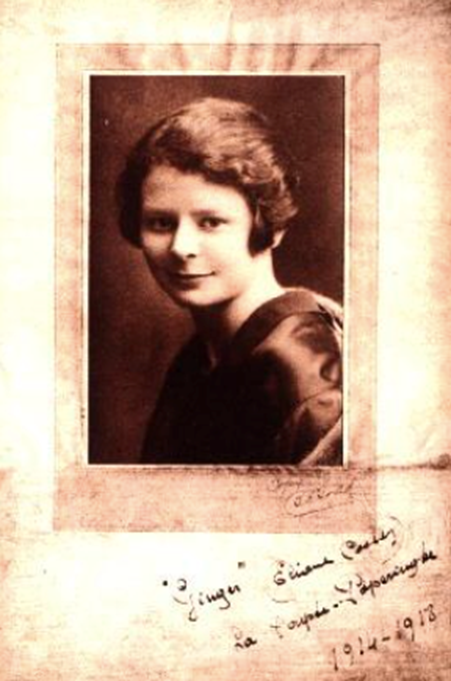

‘Ginger’

Perhaps the Cosseys’ greatest assets were their three daughters, Martha, Marie-Louise and Eliane. At the outbreak of the war the girls were respectively 19, 16 and 12 years of age. The youngest, Eliane, was a slender and very attractive red-haired girl, nicknamed 'Ginger' by the café’s officer-clientele. Such was her fame that her parents’ establishment soon became known as 'Ginger's', instead of its previous French name. This young girl seems to have had an amazing, almost hypnotic, influence on her officer customers. She was simply adored. ‘Any defects in the cuisine or in the quality of the champagne were more than compensated for by the honour of being chosen as her partner in the exhibition dance which she gave with the utmost decorum as the evening drew on’. (TTH p14)

Edwin Campion Vaughan, a British officer, wrote in his diary in 1918: ‘The two rooms were full of diners but we found a table in the glass-roofed garden. A sweet little sixteen-year-old girl came to serve us. I fell a victim at once to her long red hair and flashing smile. When I asked her name, she replied "Gingair" in such a glib way that we both gave a burst of laughter. We had a splendid dinner with several bottles of bubbly, and Ginger hovered delightfully about us.’ (‘Some Desperate Glory. The Diary of A Young Officer, 1917’, pub. Frederick Warne 1981) Favoured guests might be given an autographed picture. These were highly sought-after.

After the war new kinds of British visitors appeared – sober and often sadly searching for their lost relatives - and so ‘La Poupée’ was re-styled as a ‘tea shop’ – the first to be so-called in Poperinge.

Very little is known about Eliane/’Ginger’ after 1918. Accounts on websites and in guidebooks seem to rely on the same unnamed source or sources. They all say the same things: she married a businessman from Bruges; she emigrated to the UK and lived in London; she attended a celebration of the founding of Toc H in 1928 at the Albert Hall; she died in 1942, aged only 40 as a result of injuries suffered in the Blitz. (So, this year is the 80th anniversary of her death.) An unidentified contributor to the Great War Forum website wrote on 28 March 2017: ‘Eliane Cossey was my grandmother her son is my father although she died when he was only 16 she also had three daughters.’ Eliane’s older sister, Marie-Louise, married a British officer whom she had met at her father's café. Later, after having lived in Ostend for a while, the couple moved to England where Marie-Louise died in 1966.

‘La Poupée’ was sold and renamed as the ‘Café de Ranke’ (The Hop Bine Cafe) which for many years flourished also as a bakery/confectioner’s shop. Some years ago, I met the owner in the town square and he told me that the story that ‘more champagne corks popped in la Poupée than shells exploded on the Western Front’ may well have some substance. After he had bought the café he could open the door into the cellar only with great difficulty because it was jammed by a heap of champagne corks! Recently, it became solely a café again and renamed as it was during the war – La Poupée. A diamond shaped text panel nest to the door reminds us of the role the café played in the Great War.

Talbot House (Toc H) and Tubby Clayton

A senior army chaplain, Neville Talbot, had instructed his subordinate, Chaplain Philip (Tubby) Clayton to create a rest and recreation centre for soldiers in Poperinge. The ‘Top Brass’ were well aware of the notoriety of Poperinge and the numerous temptations it offered soldiers beyond generous helpings of ‘oofs et freets’.

Tubby Clayton chose to base the centre at the Coevoet Camerlynck house – whose owner, a wealthy hop merchant, was leaving for the south of France. On the condition that the British repaired the damage done by German shellfire, he set the rent at 150 Belgian Francs (the equivalent of £2 at 1915 value) per month. Clayton styled the house as ‘Every Man’s Club’ – ie every soldier’s club, regardless of rank. It was opened in December 1915 and named ‘Talbot House’ in memory of Lieut. Gilbert Talbot (Neville Talbot’s younger brother who had been killed earlier that year).

Talbot House soon became known by its initials TH and then in the radio signallers’ phonetic language of the day – Toc Aitch (Toc H – today it would be ‘Tango Hotel’)

No rank and no orders!

Toc H was a remarkable place. One of Tubby Clayton’s mottos was ‘All rank abandon ye who enter here’. This was significant in a garrison town where officers and ‘Other Ranks’ were completely segregated (‘Other Ranks’ were strictly forbidden to enter the town square where the officers frequented clubs and cafes). Very senior officers (including General Plumer and the Earl of Cavan) were recorded as visiting Toc H. Indeed, the Earl of Cavan wrote the foreword to Tubby Clayton’s memoir ‘Tales of Talbot House’ published in 1919

Tubby was very skilled in raising money for looking after ordinary soldiers. For example, if an officer stayed at Toc H and asked for a sheet and pillow case for his camp bed Tubby would request 1 shilling (5p). The sheet and pillowcase would never appear and the officers never complained – they knew what Tubby was up to and where their money went, initially, and before he spent it, into what he called the ‘officers’ box’.

Tubby ruled that no orders were to be given in Toc H but Tubby’s soldier guests always responded to Tubby’s requests as if they were orders. So, when he suggested one day that Toc H could do with a piano to entertain the troops, very quickly three pianos were discovered and Tubby was invited to ‘scrounge’ one of them which he did within a couple of days. In fact, he got two and gave one away to another Padre. The one he kept is still at Toc H and perfectly playable (as of 20 October 2022). (TTH p23)

Tubby created a well-patronised library. Tubby requested that the borrower leave his cap as security, knowing that the if the soldier lost his cap his army pay would be docked. Tubby never seems to have lost a book.

Supplies of tea and coffee were unlimited – but no alcohol in any form. There were no complaints about this – it was freely available, anyway, within a couple of hundred metres or so from Talbot House, outside the ‘officers only’ area, and many soldiers wanted to avoid the fights that often broke out in the estaminets.

As the number of soldiers coming to Toc H increased the neighbouring hop store was taken over and used for services and activities such as lectures, film shows, and concerts. The performers were soldiers – some of whom, when they returned to civilian life, became professionals. It is believed that the comedians Flanagan and Allen may have first met and performed at Toc H. (They began to work together professionally in 1926.) Flanagan was a Sergeant and Allen a Captain. (Many years later Flanagan wrote and performed the Dad’s Army theme tune ‘Who do you think you are kiddin’ Mr Hitler’)

The Chapel – the ‘Upper Room’

Tubby created a chapel in the loft of Toc H – originally used as a linen store and drying room. Tubby called this the ‘Upper Room’. This name has biblical significance. In an upper room, (mentioned specifically in Mark 14: 15 and Luke 22: 12) in a house in Jerusalem, the night before his death, Jesus reassured his disciples at the ‘Last Supper’: ‘I will not leave you comfortless: I will come to you’ and ‘…. because I live, ye shall live also.’ (John 14: 18-19). The altar is a carpenter’s bench salvaged from close to the house. Tubby thought this was very appropriate – Jesus’ father (‘father on Earth’, to Christians) was a carpenter and Jesus may very well have learned carpenters’ skills. Tubby, himself, was a keen amateur carpenter. Services were always well attended and by Tubby’s own estimate 10,000 soldiers attended Holy Communion at Toc H. (TTH p82) Again, by Tubby’s own estimate, in 1919 2,000 ex-soldiers were candidates for ordination in the Anglican Ministry. Tubby noted approvingly that class divisions had ‘softened’ during the war and that these men were of ‘every type and social standing’. ‘…. in Talbot House the men were first enrolled.’ (TTH p91)

The Upper Room was deemed ‘wholly unsafe’ by the military authorities and with 150 men attending a Service it ‘rocked like a huge cradle’. (TTH p68) Tubby and the men were entirely unperturbed. Tubby lists the ‘ornaments’ of the Upper Room including the ‘splendid crucifix made and presented by 120th Railway Construction Company’ and the ‘great standard candlesticks made out of old carved bedposts’ – the gift of a Canadian gunner. ‘This inventory of ornaments is, perhaps, a tale of little worth in the judgement of those who are accustomed to the lavish elegancies of a home parish. Yet such will bear with me, when they remember how far a little beauty went amid such surroundings as ours.’ (TTH p72)

The oil lamp used by Tubby Clayton in the Upper Room at Talbot House is known as the Lamp of Maintenance. It is lit for 24 hours every year on Tubby Clayton’s birthday from 11-12 December.

In the Upper Room is the original wooden cross which marked the grave of Lieutenant Gilbert Talbot. There is a story: One night in the mid-1990s the doorbell rang at Talbot House. When the door was opened there was no-one to be seen in the street, but there was a large black plastic bag left on the doorstep which was found to contain a wooden cross. The metal strips attached to the cross showed the following:

LIEUT. G. W. K. TALBOT

7/ RIFLE BDE

30-7-15

The whereabouts of this cross up to that moment still remain unknown, but someone had been keeping it safe for all those years. Most of the original crosses were burned when they were replaced after the Great War with gravestones. (From greatwar.co.uk website.)

1917 & 1918

Tubby Clayton wrote of the soldiers’ mood at the closing of 1917. The time was ‘…. supremely wretched’ following 3rd Ypres. ‘The defeat of our Summer hopes and the full extent of our autumn losses were common, though whispered, knowledge.’ (TTH p95) For the first time ‘Rancour and ill-feeling between officers and men forced themselves on my attention …’ Fully aware of the crisis in morale, since deserters were also now turning up at Talbot House seeking sanctuary, Tubby started up ‘groaning circles’ where grievances could be aired. These were passed on to the Army Staff who seemed to have listened and made some attempts at amelioration. (TTH p96)

German shells did not fall on Poperinge in large numbers for most of the war. Tubby reckoned that Poperinge was shelled on average once a week – and not intensely. However, in the Spring of 1918, during the last attack by the German army the shelling intensified. ‘On March 23, just before midnight, a great crash woke me.’ (TTH p62) ‘Then I went out and found the street twenty yards away blocked with debris.’ The ‘Hotel Cyrille’ (an ‘officers only’ establishment) had been hit and Tubby tried to find survivors. Cyrille, his wife and their four maids had all been killed. Cyrille’s ‘head could nowhere be found until the following day, when it was discovered in the house opposite – blown by a grim jest of death through a broken window.’ (TTH p64)

Talbot House had to close between 21 May and 30 September 1918. Poperinge had become too dangerous for it to remain open. It then stayed open until January 1919.

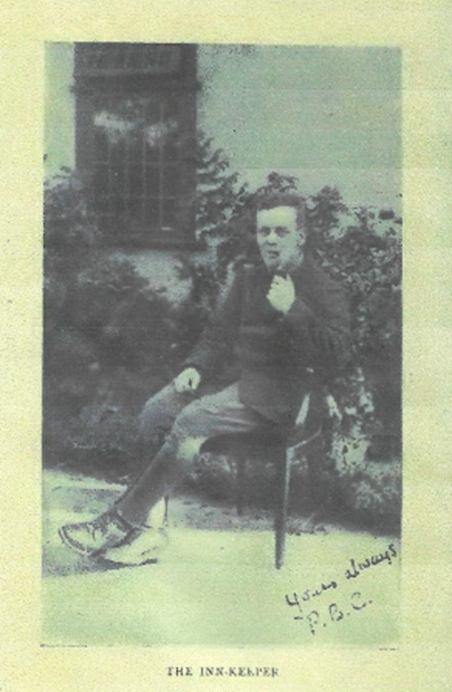

Funding Talbot House

Captain L F Browne RAMC contributed a chapter to Tubby’s memoir, ‘Tales of Talbot House’ entitled ‘The Innkeeper’ (ie Tubby). In a kind of humorous aside Captain Browne wrote about Tubby’s financial record keeping which he had been ordered to enquire into by Army Headquarters. Tubby’s accounting turned out to be ‘creative’ (to use a modern term). A more accurate description would be that it was simply non-existent. There certainly was an ‘account book’ – with meaningless entries. There were receipts – a cupboard full ‘with inscriptions in French, Flemish and English … but there was no order or system ….’ Army Headquarters were fobbed off with the assurance that ‘the accounts were being audited’. Audited accounts were never produced. ‘But, strangely enough, further probing after several months revealed the fact that the House had been the gainer to a large extent by the “defalcations” of the innkeeper.’ (TTH p116) Measuring accumulated assets against liabilities, Talbot House was, in fact, firmly ‘in the black’.

(defalcation = a fraudulent deficiency in money matters. Oxford English Dictionary.)

After the war the owner of the house returned and sold it to Lord Wakefield of Hythe (Wakefield Oils – ‘Castrol’ etc.) in 1929 for £9,200. Lord Wakefield donated it to the Talbot House Association.

During the Second World War Poperinge was occupied by the German Army from May 1940 to 6th September 1944. A team of local people secretly emptied the house of its contents, splitting them throughout the town and finding a hiding place for each individual item.

Toc H was used by the Germans as billets. Unknown to them a tunnel under the garden was being used as a shelter for Allied aircrew as they were passed along the escape route through Belgium. With the liberation of Poperinge in 1944 every single item was brought back to Talbot House.

From 1922 to 1962, Tubby Clayton was Vicar of All Hallows-by-the-Tower in the City of London. He had much to do with helping impoverished East Enders in the difficult times of the 1930’s and the Blitz of 1940-41 when his church was badly damaged.

Tubby took great pride in describing himself as a scrounger – a skill which he developed to perfection during his time at Talbot House. Perhaps his most remarkable act of scrounging was when, as a protestant Church of England vicar, he persuaded the local Roman Catholic Diocese to give him money - on the grounds that he knew better how to spend it on the poor and deserving!

Other names/buildings in Poperinge:

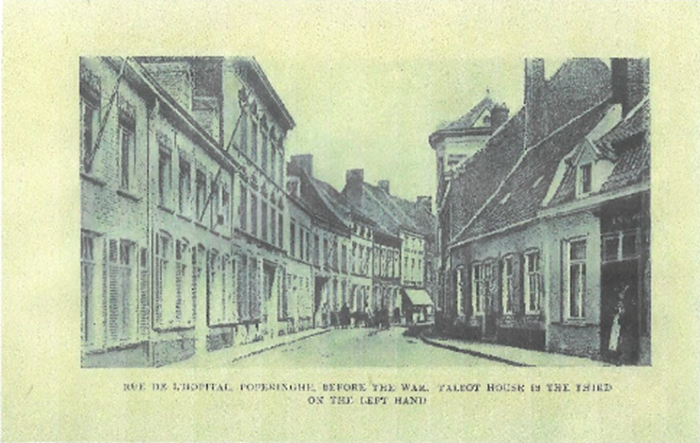

On Gasthuis Straat (formerly Rue de l’Hopital):

No. 12, ‘Skindles’ – Named after a hotel and restaurant at Maidenhead known to young officers. The name was certainly easier (and quicker) to say than its original name: ‘Café a la Bourse du Houblon’ (Hop Market Café). It was run by Madame Beutin and her daughters, Maria, Zoe and Lea. Subsequently a pharmacy, it is now a shop named ‘it’s Bling Bling’. A new, larger, Skindles was created at No. 57 and is still open. The original hotel at Maidenhead has now been demolished. There is still a restaurant on the site.

No. 26, Hotel Cyrille – ‘Cyril’s’ (now ‘Music – Shop’) – run by Cyrille Vermeulen and his wife. 1918 – direct hit by a German shell, Cyrille, his wife and their four maids were killed. (See above.)

No. 43, Talbot House – the famous exception to the above which were strictly ‘Officers Only’. This was ‘Every Man’s Club’. ‘All rank abandon ye that enter here’ was Tubby Clayton’s order – the only order, since giving other orders was forbidden at Toc H.

In the Square: the Town Hall (Stadhuis/Hotel de Ville). Looks old but built in 1911. Used as a Divisional HQ. ‘Death Cells’ – where soldiers condemned to be ‘shot at dawn’ were kept before their execution. In the courtyard – the post the condemned men (27 in total) were tied to. 17 are buried in Poperinge New Cemetery.

* The Reverend Philip Thomas Byard Clayton CH MC FSA (12 December 1885 – 16 December 1972), known as ‘Tubby’ Clayton.

Philip Clayton was born in Australia, to English parents who brought him back to England when he was two years old. Educated: St Paul’s School, London and Exeter College Oxford (graduated in Theology). Ordained as a priest of in the Church of England. Served as curate at Portsea, Hampshire, from 1910 to 1915. Became an army chaplain. Nicknamed ‘Tubby’ because he was not the slimmest man in uniform!

References:

T B Clayton ‘Tales of Talbot House 1915-1918’ T B Clayton, Chatto & Windus, 1919. See TTH and page numbers in text above.

Bertin Deneire, Poperinge – ‘The Story of Gorgeous Ginger’ No longer accessible as a website.

Conversations over the years in Ypres and Poperinge with, among many others, Jacques Ryckebosche, formerly Warden of Talbot House, Poperinge. He has a fund of stories about Tubby Clayton, the House and the antics old soldiers got up to in the cafés of Poperinge right up until the 1980’s. In 1982 there were actually over 80 ‘Old Contemptibles’ still alive and many more who served later. Some still made visits to Ypres and Poperinge, staying at Toc H.

Article by Peter Crook October 2022