Blessed be St Enodoc : The Great War Story of a Cornish Church and those buried there.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Blessed be St Enodoc : The Great War Story of a Cornish Church and those buried there.

There can be few churches that sit in so picturesque a setting as that which frames St Enodoc on the north Cornish coast. The poet John Betjeman wrote a paean to the church which is deeply felt, it is where he chose to be laid to rest when he died in 1984, having lived in a house in nearby Trebetherick, bought in 1960 as a nostalgic consequence of spending gloriously sunny days in the area as a boy on holiday with his childhood friends – named in the last line of the poem.

Blessed be St. Enodoc, blessed be the wave,

Blessed be the springy turf, we pray, pray to thee,

Ask for our children all the happy days you gave

To Ralph, Vasey, Alastair, Biddy, John and me.[1]

From Trebetherick by John Betjeman

Flanked by mighty Brea Hill and the well-manicured greens and fairways of the golf course, which is in turn fringed by the dunes that lead to the golden sands of Daymer Bay and the turquoise blue of the sea, the eye is drawn to the small crooked spire silhouetted against a rich azure sky.

Above: St. Enodoc Church (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

Legend has it that the church was founded on the site of a cave inhabited by a hermit named Enodoc. It dates back to at least the 12th century, with additions in the 13th and 15th centuries. From the 16th to the mid-19th century, the church was almost entirely buried by the wind-blown sands from the adjacent dunes, causing it to be named colloquially as Sinkininny Church, the only part of the structure still visible being the spire. The church lies within the parish of St Minver, and in order to earn his stipend, the local vicar was obliged to conduct at least one service a year there; he and his congregation would be lowered through an opening in the roof in order to do so [2]. It was excavated and renovated in 1863 and is now protected from the drifting sands by a rectangular thicket of bushes.

It is a stunning location and one can see why Betjeman chose to spend eternity there. Also buried here, in the southwest corner of the graveyard are two casualties from the Great War; a soldier and a sailor, unknown to each other in life, now, in perpetuity, neighbours in the afterlife. One a local man, the other from over the seas. Here lies Private 22128 Christopher ‘Kit’ Runnalls of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, and an unidentified crewmember of the SS Armenian, his headstone simply engraved A Seaman of the Great War: Known Unto God.

Private 22128 Christopher Runnalls, Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry

Christopher Runnalls was born in 1882 at Cardinham, Cornwall, four miles to the east of Bodmin, to a wood ranger named John Runnalls and his wife Mary (née Wherry). By 1891 Christopher, his father (now a gamekeeper), mother, and his elder siblings, Francis age 13 and Mary age 10, were living at 2 New Bridge Lodge on the Glynn estate adjacent to the River Fowey, which runs through the densely wooded Glynn valley. By 1901 they had moved to another cottage on the estate named Woodman’s Lodge, where Christopher, aged 19, was employed as a Wall Mason; now joined by a younger brother named Herbert age 7. On 27 March 1907, at the age of 25, Christopher married Susan (Susie) Jane Buse, aged 18 at St. Minver, around 15 miles northwest of Cardinham, and by the time of the 1911 census the young couple are shown as living at Polzeath, St Minver, nr Wadebridge, with Christopher still plying his trade as a Wall Mason.

Above: Cardinham, Cornwall (Image: Cardinham Parish.net)

War came, and as it progressed, Christopher enlisted with the 10th (Service) Battalion (Cornwall Pioneers), Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI) at Wadebridge, Cornwall. Unusually, the battalion was raised by the Mayor and citizens of Truro in March 1915 – rather than the War office – an arrangement reminiscent of the old-fashioned militia or volunteer force. The only two officers were a retired Colonel of the Royal Engineers, Dudley Acland Mills, and the noted poet, novelist, critic and editor of The Oxford Book of English Verse, Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller Couch (known as ‘Q’), who, upon the outbreak of war and although lacking in military experience, ‘had taken a leading part in the formation of the Territorials in Cornwall […] he was kept busy recruiting, organising meetings, aiding the national effort, bringing home the sense of danger in remote country places as yet hardly aware of it – both by speech and writing’ [3].

Quiller Couch had to juggle his commitments as Professor of English Literature at Cambridge with the demands of army life: ‘From March to October 1915, Q was on leave from the University on military duty at home. He was given a temporary commission to raise and train a pioneer battalion [the aforesaid 10th] of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. In the midst of all this he had to set examination papers for the Tripos, and was a bit late. “We are almost desperately busy here…on top of my share of recruiting the War Office made me a temporary lieutenant to work up one company.” Men were pouring in, “and I am left alone with the O.C. to wrestle with a thousand details of clothing contracts, army forms, billets, etc., besides taking parades and sitting on minor offences.” With the acute shortage of officers the Colonel and he had to make do as best they could.’ [4]

Above: ‘A’ Company 10th Battalion Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry Section 4 (Image: Pinterest)

Quiller Couch was working from 7:30 in the morning until 1:00 the following morning, drilling the fresh recruits, leading six mile route marches and dealing with sick parades before tackling his academic work at the end of the day when he would burn the midnight oil. Army standards of turn-out were alien to some of these Cornishmen, and Q would have to inspect the men’s chins every morning at 9:30 to ensure they were clean-shaven, and ‘Then there were toe-nails to be looked at. After taking his company for a bathe in the sea, he found that he needed to cut the toenails of a large number – “and they were toe-nails, too!” [5] It must have been an extraordinary sight to see this Knight of the Realm, this eminent man of letters, tending to the feet of lower-ranking soldiers such as Christopher.

On one occasion, after a demanding route march into Fowey, Q generously invited all of the men back to his house, The Haven, for tea. The Haven overlooked Polruan Ferry with a spectacular view over the Fowey estuary and out to sea. Trestle tables were erected that covered the lawn, and Q’s wife, Lady Louisa, served the men, ‘this was the kind of occasion Lady Q could rise to, though they ate the house bare.’ [6] Q and the Colonel had now raised two combat-ready companies, and the War Office urged them to continue until they’d formed a whole battalion. They worked manfully to this end and it was a remarkable achievement when they eventually succeeded; the War Office formally adopted the 10th Battalion on 24 August 1915. Q handed over the reins and was able to devote more time to the world of academe.

Above: Lady Quiller-Couch serving tea to the men of the tenth battalion of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. (Image: Pinterest)

Having received their orders for France, the 10th DCLI entrained at Plymouth on 16 of June 1916, arriving at Southampton around 8:00am the following day. After spending two days at the rest camp, the battalion embarked on the SS Princess Clementine, leaving Southampton docks at 6:15pm. Having sailed through the night, they made landfall at Le Havre the following morning, disembarking at 8:30. The battalion travelled via train to Bruay and then marched 13 miles to Villers au Bois, a commune around 9 miles northwest of Arras, where they joined the 2nd Infantry Division on 23 June. As the Division’s Pioneer battalion, their primary function was in construction and engineering, and men recruited for these units needed the qualities of strength and stamina; manual workers conditioned through hard, physical toil. The Cornishmen, coming from a background of agricultural labour and tin mining, were well suited to this role. But they were not just a labour force, they were fighting soldiers too; often their work was carried out under fire. Whilst supporting front line troops during an attack, they were required to strengthen and buttress newly won enemy trenches and earthworks and inevitably would become embroiled in the fighting during a counter attack.

They went into the trenches at Villers au Bois on the 24th, and the battalion’s war diary records the first day’s events:

A & B [companies] commenced work in the trenches under the supervision of the RE’s (East Anglian Field Coy RE). Work consisted chiefly of draining and improving communication trenches, extension, tunnelling under the road for joining of communication trenches and erecting dugouts in the reserve trenches. Most of the work was carried out in shifts. C and D Coys remained in billets resting [7].

They spent the best part of a month at Villers au Bois, before receiving orders to move. By the end of July they had joined the Battle of the Somme; the 10th DCLI became immersed in the titanic struggle for Delville Wood. On 27 July, the battalion were detailed to carry ammunition and rations up to the front line, arriving about 9.30pm where they ‘came under an extremely heavy shellfire. A Coy sustained 29 casualties including 8 killed, 4 missing and the rest wounded. Lieut. C.H. Reynolds was slightly wounded and Lieut. R.H. Davenport was sent to hospital suffering from shell shock’ [8].

Above: Trenches at Delville Wood 1916. (Image: blogspot.com)

The following day, the 28th, most of the battalion were working as a carrying party again, when they ‘were ordered to do a counter attack in Delville Wood. D Coy appears to have done very well and was highly praised by OC 2nd South Staffordshire Regiment [who was in overall command]. Casualties all told were about 12 wounded and 1 missing’ [9]. They continued serving on the Somme at Delville Wood, Longueval, Bernafay Wood and Trones Wood into August, and by September the battalion were deployed further north on the western front in the Hebuternes sector. At some point during this period, possibly whilst at Delville Wood, Christopher was seriously wounded and was transported back through the medical chain of evacuation to a hospital ship bound for England. Christopher was taken to the 2nd Northern General Hospital in Leeds, a former teacher training college now accommodating 60 officers and 2039 other ranks. Christopher never recovered from his wounds and died here on 10 September 1916 aged 34.

Above: 2nd Northern General Hospital, Leeds. (Image: Yorkshire Evening Post)

Christopher was brought home by Susie to rest in the Buse family plot at St Enodoc, his father-in-law William’s slate-grey headstone adjacent to the white Portland CWGC headstone marking Kit’s grave.

Above: William Buse’s headstone. Christopher’s can be seen in the background to the left of his father-in-law’s. (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

That Christopher was much loved and sorely missed is clear. His family, including his in-laws, published the following In Memoriam notices in the Cornish Guardian on the first anniversary of his death:

RUNNALLS. In ever-loving memory of our dear son who died from wounds received in France, Sept. 9th. 1916 aged 34. Sadly missed by father, mother, brothers and sister. Never shall his memory fade.

RUNNALLS. In loving memory of Kit, beloved husband of Susie, who died of wounds received in action, Sept. 10th, 1916, aged 34. A soldier’s grave—a touching thing, where loving hands some flowers can bring. But God in His great loving care, will guard my darling lying there.

RUNNALLS. In loving memory of Christopher Runnalls, died of wounds received in action on Sept. 10th, 1916. Sadly missed by his loving mother-in-law and sister-in-law, E and M. Buse. Though death divides fond memory clings.

RUNNALLS. In loving memory of Pte. C. Runnalls (Kit), who died of wounds received in action, Sept. 10th, 1916. Sadly missed by his brother-in-law and sister-in-law, also little niece. —Charlie, Beat and Elsie. One of the dearest, one of the best, May God grant him eternal rest.

In loving memory of Pte C. Runnalls, died of wounds, Sept. 10th. 1916, dearly-loved brother-in-law of M. and J. Richards and loving uncle of Dorothy; also of Pte F. Buse, killed in action, Sept. 14th, 1916, dearly-loved cousin of Meg, Jack and Dorothy: also of our dear friend. Albert Male, killed in action August 25th, 1916. Their duty nobly done [10].

Above: Headstone of Private Christopher ‘Kit’ Runnalls, 10th Battalion DCLI. (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

A Seaman of the Great War: Crewmember of the SS Armenian

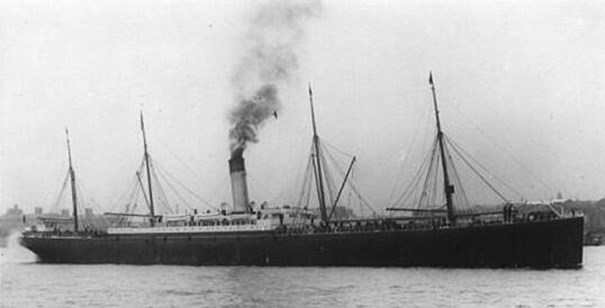

The SS Armenian was a cargo liner built in 1895 by Harland & Wolff in Belfast – the shipyard that built the Titanic – for the Leyland Line, a British transport shipping line. It was employed on the Liverpool to New York City cargo service before being requisitioned during the Boer War, initially as a transport ship carrying horses, subsequently as a prison ship at Cape Colony and further to convey Boer prisoners of war to Bermuda and India. The management of the ship was taken over by the White Star Line on 20 March 1903. Upon the commencement of the Great War, the Armenian underwent a refit with stables installed as a horse and mule transport ship.

Above: SS Armenian. (Image: Ship Index.org)

On 28 June 1915 the Armenian was bound for Bristol having set sail from the curiously named port of Newport News in Virginia, US, carrying a cargo of over 1400 mules for the allied war effort. At around 6.30pm, the vessel was proceeding north-eastwards off the north Cornish coast around twenty miles from Trevose Head en route to the Bristol Channel, when a watchman sighted a German U-boat and sounded the alarm. The captain, James Trickey, ordered full steam ahead in an attempt to shake off the pursuing submarine but to no avail. The U-24’s commander, Rudolf Schneider, signalled the Armenian to stop and surrender, firing two shots across her bow, but still Trickey tried to outrun the pursuer. The U-boat started shelling the Armenian, scoring direct hits on the engine room, the wireless operator’s cabin and shooting away the steering gear and causing at least a dozen fatalities.

Above: Submarine U24 (Image: Wikipedia)

Trickey realised the position was hopeless and surrendered. The Germans allowed the survivors to board the remaining, undamaged lifeboats before sinking the Armenian with two torpedoes fired into the stern of the vessel. A Belgian steam trawler, the President Stevens, picked up the survivors the following day. It was reported that twenty-nine souls were lost, the majority of them Americans: many of those on board were muleteers hired at Newport News prior to sailing, mostly African-Americans. It is said that twelve of these muleteers refused to abandon their animals, choosing to stay in the hold in an attempt to calm and comfort them.

The loss of so many American lives provoked an international outrage, compounding the crisis caused by the sinking of the Lusitania just 52 days earlier when a hundred American souls were lost. It was in the interest of the allies to foster this anti-German sentiment in an attempt to bring the US into the war, and the British and French press were intent on inflaming the situation accordingly. The US State Department commenced an investigation into the affair and officials initially believed that the U-boat Commander, Rudolf Schneider, had failed to comply with the rules of engagement regarding merchant ships, in that the vessel should have been subject to a ‘stop and search’ before facilitating the safe passage of the crew prior to the destruction of the craft. However, as the ship was engaged in assisting the allied war effort it was considered a legitimate target and it became clear that Schneider had signalled the Armenian to stop and had only commenced fire when Trickey had tried to outrun the U24, thus the rules had been complied with. The crisis abated and the US did not enter the war until April 1917.

Inevitably bodies began to wash up on the north Cornish coast. A local newspaper, under the headline The Torpedoed Armenian Bodies Washed Ashore, published the following report on the 16 July 1915:

On Saturday Mr. John Pethybridge (Coroner), of Bodmin, held an inquest on the bodies of four sailors which were picked up by the fishermen of Port Isaac and landed. As one of them had a lifebelt with S.S. Armenian upon him, it is believed they belonged to that ship which was torpedoed by a German submarine some ten days’ ago, a few miles off Trevose Head. Two of them were men of colour, on one of which was an insurance card bearing the name of George Smith, Portsmouth (This would appear to refer to Portsmouth in Virginia, US, which sits across the James River from Newport News). The jury returned a verdict of ‘'Found drowned”. In the afternoon their remains covered with flags and followed by Boy Scouts under Miss Hyde, their Scoutmaster, carrying bouquets, were taken to Saint Endellion for burial. Since the inquest three more bodies have been brought in at Port Quinn close by, and two at Port Isaac. Mr. A.C. Pomeroy, deputy coroner, has also held several inquests on bodies which have been washed ashore on other parts of the coast [11].

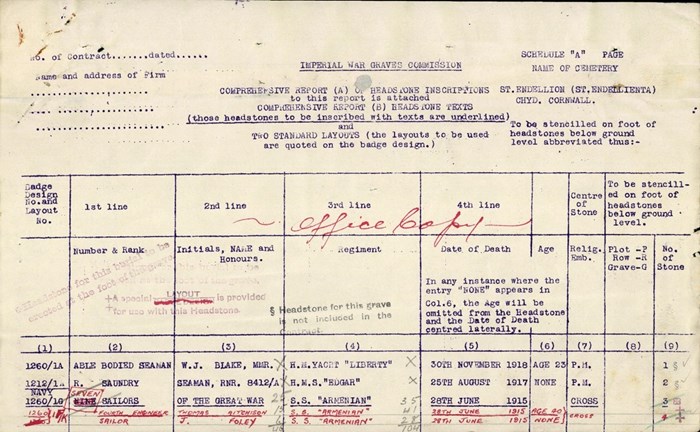

The graveyard at St Endellion Church, in the neighbouring parish to St Minver that covers Port Isaac and the surrounding area, contains nine graves of crewmembers from the Armenian that would account for those bodies featured in the report. Initially they were all listed as ‘unknown’ but two were subsequently identified; Fourth Engineer Officer Thomas Aitchison, 40 years old, and Able Seaman John Foley, 53 years old.

Above: CWGC schedule of layouts for headstones in St Endellion Cemetery with alterations showing subsequent identification of two crewmembers of the SS Armenian. (Image: Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

Above: CWGC headstone for the seven unidentified seamen at St Endellion (Image: thebignote.com)

Another body was washed up near St Teath. The Cornish Guardian published the following report under the headline Delabole Jury and a Coroner – Post Office Mistake:

On Sunday a body was washed ashore at St. Teath, about four miles from Delabole. It was first seen by Mr. E. Jenkin, of Delabole, while walking on the cliff, and it was taken to a building at Dinnabroad. The police constable at Delabole received telegraphed instructions from the coroner on Monday to arrange an inquest at 6 p.m. Being an extremely short notice, he was obliged to summon the majority of the jury from Delabole, as the immediate locality is thinly populated. The jury set out, some walking, others on bicycles, and after covering a distance of three miles found that the coroner had not arrived. Being an out of the way place, it was thought he might have missed his way, and as he had been holding inquests at Port Isaac, Polzeath, and Padstow, that same day, they were prepared to allow him a little grace. At 9.20 however, the jury's patience became exhausted, as no coroner had arrived or word given of the reason of his absence, and they returned home.

We are informed by Mr. A. C. Pomery, deputy coroner, of Bodmin, that the telegram he sent to the police constable on Monday asked him to fix the inquest for “to-morrow" at the time stated. The Post office in transmitting the message omitted the word "to-morrow," Hence the mistake.

An inquest was conducted on 'Tuesday last at Dinnabroad Farm, St. Teath, by Mr. A. Pomery (deputy coroner), on the body of Wm. Henry Perks, which was found in the sea at Dinnabroad Cliff, the previous Sunday morning.

Ernest Jenkin gave evidence as to finding the body. He said he saw it in the sea and with assistance got it out. It was the body of a man who was fully dressed and wore a lifebelt, which bore his name.

Jane Perks, said William Henry Perks was her husband. They lived at 7, Wedmore Road, Grangetown, Cardiff. He was a baker, 27 years of age, and had been to sea about eight years. Witness last saw him alive on 29th May last a Cardiff; he left to join the S.S. Armenian. They were bound for Newport News, Virginia, U.S.A. He wrote witness a letter from that place and she received same on 27th? June. Witness had not heard anything of him since. She received a message from the police the previous day, and at once proceeded to Cornwall. She had seen the body that was found and identified it and various articles of clothing.

PC Pomery, Delabole, stated his attention was called to the body, and he inspected it and the clothing. He found a telegram and two certificates both bearing the name of William Henry Perks, of 7. Wedmore Road.

The jury returned a verdict of "Found drowned."

The SS Armenian was homeward bound for Bristol, and belonged to the Leyland Line of Liverpool. She was torpedoed few weeks ago [12].

The fate of William Henry Perks was expanded on in an article in the Western Mail under the headline An Armenian Victim – Inquest Story of a Cardiff Man’s Fate, but contradicts the above article with regard to the lifebelt and whether it bore his name or not:

An enquiry was held at St. Teath relative to the death of William H. Perks of 7 Wedmore Road, Grangetown, Cardiff, whose body was picked up near Dinnabroad Cliff, St. Teath, the previous Sunday.

Jane Perks, the widow, said her husband was a baker on the Armenian. He was 27 years of age, and had been going to sea about eight years.

Police Constable William Pomeroy deposed that the body, which was decomposed, was fully dressed. Deceased also had on a lifebelt, but there was no name on it. On examining the body he found a small wound in the forehead and another in the neck. They had the appearance and felt like small shot wounds.

A friend of deceased stated that Perks was an excellent swimmer, and it had been stated by some who had been saved that deceased was shot and killed.

A Juryman stated that at the time of the sinking of the ship they heard firing off the coast for about an hour, but could not tell what it was.

“Found drowned” was the verdict, and the jurymen’s fees were given to the widow [13].

Three more unidentified crewmembers were buried at St Minver, the main parish church for the whole Camel Estuary sited in the actual village of the same name where, incidentally Christopher and Susie were married.

Above: Tower Hill Memorial to the Merchant Navy (Image: War Memorials Online.org)

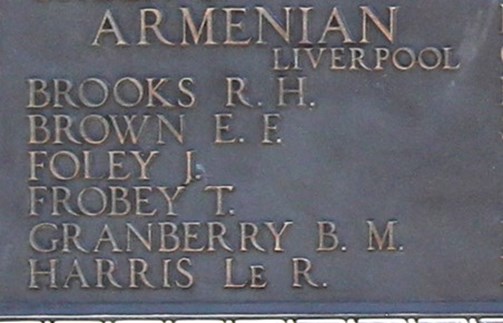

The names of the crewmembers of the SS Armenian who lost their lives on the 28/06/1915 and who have no known grave are listed on the Tower Hill Memorial to the Merchant Navy in the gardens of Trinity Square opposite the Tower of London:

Brooks, R.H. (43), Head Foreman, Mercantile Marine, b.1872, Bournemouth

Brown, E.F. (22), Carpenter, Mercantile Marine, b.1893

Frobey, Thomas (22), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1893

Granberry, B.M. (39), Assistant Foreman, Mercantile Marine, b.1876

Harris, Le Roy (22), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1893

Henry, Julius (21), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1894

Jackson, Robert (28), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1887

King, Thomas (28), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1887

Little, Andrew (22), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1893

McCarthy, James (28), Ordinary Seaman, Mercantile Marine, b.1887, London

Monroe, J.M. (48), Assistant Foreman, Mercantile Marine, b.1867

Oakes, Walter (22), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1893

Pauwells, F (47), Able Seaman, Mercantile Marine, b.1868, Belgium (Crew list transcription gives name as Panwells)

Perks, William Henry* (27), Chief Cook, Mercantile Marine, b.1888, Cardiff

Ryckcerd, Henry (23), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1892

Small, Howard (22), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1893

Smith, John (24), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1891

Stone, Harry (26), Assistant Foreman, Mercantile Marine, b.1889

Sutton, S.R. (48), Assistant Foreman, Mercantile Marine, b.1867

Vivo, Jorge. S (22), Surgeon, Mercantile Marine, b.1892 Utuado, Puerto Rico

Wall, Edgar (28), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1887

Williamson, E. (37), Assistant Foreman, Mercantile Marine, b.1878

Yansson, John. W. (51), Able Seaman, Mercantile Marine, b.1864, Sweden (Crew list transcription gives name as Jansson)

Young, William (29), Muleteer, Mercantile Marine, b.1886

* Despite the identification of his body by his wife (see articles above), William Perks’ name appears on the memorial.

Above: One of the panels on the Tower Hill Memorial (Image: Benjidog.co.uk)

The following two crewmembers are commemorated on the Bombay 1914-1918 Memorial, Mumbai:

Abdul Muhammad (23), Fireman & Trimmer, Indian Merchant Service, 1892 Zanzibar

Ahmad Bin Aslam (32), Quartermaster & Sailor, Indian Merchant Service, 1883 Sarawak (Crew list transcription gives name as Amat Bin Haslan)

In 2007, the nautical archaeologist, Innes McCartney, discovered the wreck of the Armenian, still intact and sitting upright in about 95 metres of water. The ship was easily identified by the huge amount of mule bones found in the vessel’s hold. It became known as ‘the mule ship’ and ‘the bones wreck’, the latter name used in the title of a documentary broadcast on the History Channel. One of the divers, Chris Lowe, was interviewed by BBC Radio Cornwall for a broadcast in 2008, the media interest demonstrating that the story of the Armenian haunts us still.

Above: Trevose Head – looking out to the Atlantic (Image: Cornwallcam.co.uk)

Above: The Camel Estuary where it flows into the Atlantic, looking west. Trevose Head is in the distance (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

Those of us that have an abiding interest in the Great War spend our time forensically poring over primary sources, comparing and contrasting secondary sources, immersing ourselves in the historiography, empirically gathering evidence to build a case, to argue a point, to take an objective view on any given theme or subject. But every now and again an event comes to notice, we come upon a story, which defies all our efforts to clinically dissect and reconstruct, which affects us on a very human, and a humane, level. The sinking of the SS Armenian is such an event. Those African-American muleteers, plucked from Virginia, had scarcely more agency than the poor, doomed, animals under their care. They both, man and beast, were innocents abroad, literally swept away by the tides of war.

Above: A Seaman of the Great War – St Enodoc (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

And so here at St Enodoc, side by side in this beautiful place of consolation and contemplation, lay a Cornish soldier surrounded by his extended family, and a lone seaman unvisited by his – for his kinsfolk know not where he rests. But not unmourned, to this day, kindly souls lay flowers at his grave. In death they are comrades, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s egalitarian approach manifested in the elegant headstones marking their graves, in accordance with their guiding principle that ‘all, from General to Private, of whatever race or creed, should receive equal honour under a memorial which should be the common symbol of their comradeship and of the cause for which they died’.

Above: Headstones of Private Christopher Runnalls and an unknown Seaman of the Great War. (Photo: Paul Blumsom)

Article by Paul Blumsom

References

- Betjeman, John, John Betjeman’s Collected Poems, John Murray, London, 1960, p.60.

- Wilson, A.N., Betjeman, Hutchinson, London, 2006, p.24.

- Rowse, A. L., Quiller Couch: A Portrait of ‘Q’, Methuen, London, 1988, pp.128.

- Rowse, p.130.

- Rowse, p.131.

- Rowse, p.131.

- WO/95/1335/1 War Diary 10th Battalion DCLI, The National Archives

- WO/95/1335/1 War Diary 10th Battalion DCLI, The National Archives

- WO/95/1335/1 War Diary 10th Battalion DCLI, The National Archives

- Cornish Guardian dated Friday 14th September 1917, p.1

- Cornish Guardian dated Friday 16th July 1915, p.6

- Cornish Guardian dated Friday 16th July 1915, p.4

- Western Mail dated Thursday 15th July 1915, p.7

Websites

https://www.portisaacheritage.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/’Known-unto-God’.pdf

https://1915crewlists.rmg.co.uk/document/108622