British Divisional Commanders During the Great War - First Thoughts

- Home

- World War I Articles

- British Divisional Commanders During the Great War - First Thoughts

[This article first appeared some years ago in Gun Fire Edition 29. Although these are not dated, it is likely Gun Fire Issue 29 was published around 1995. All of these magazines are now available to WFA members' via the Member Login. Joining the Western Front Association gives you access not only to the 59 editions of Gun Fire but also to all 110+ issues of the WFA's in house journal Stand To!].

The research project which spawned this article began with a question. It was asked by Peter Lawrence, French teacher, Rugby coach and member of The Western Front Association, at a Birmingham University adult education class, on 'British Commanders during the Great War', held in Wolverhampton during the winter of 1988-89. 'Who,' he asked, 'were these generals, anyway ?'

The question was apposite. In recent years discussion of British conduct of the Great War has happily moved away from the sterile debate about personalities which characterised it for so long.(1) Attention has increasingly switched to the British army as an institution. The resulting portrait has not always been flattering, often emphasising the army's structural weakness and intellectual rigidity.(2) This is in marked contrast to admiring accounts of the German army's innovative and dynamic operational methods.(3) But whatever its limitations, few can now doubt that the British army did undertake a 'learning process' during the war. The nature of this process, however, remains poorly understood.

The recent important study of Sir Henry Rawlinson is instructive.(4) Accounts of the Great War have commonly focused either on the high command or on the frontline infantryman. The Prior and Wilson book is a refreshing attempt to look beyond these boundaries. Two things are apparent from their analysis: the first is that the British army had emerged by 1918 as a sophisticated and potent instrument of war; the second is that this process owed little to General Rawlinson.

Above: Rawlinson

Who was responsible, however, is far from clear. This article and the project from which it has grown rests on the belief that a true understanding of the evolution of the British army's operational method during the Great War must be sought not only below the level of high command but also below that of army and corps, principally at the level of the division.

The division was the basic fighting unit of the army, a mini-army in its own right, with its own infantry, artillery, logistical support, medical and training facilities. During the First World War Great Britain raised 84 divisions; three cavalry (all Regular Army), five mounted (all Territorial Force) and 76 infantry. This was an enormous number, almost certainly too great.(5) The infantry divisions included 12 that were Regular Army,(6) 15 first-line Territorial,(7) 13 second-line Territorial,(8) 18 First New 22 Army(9) and 12 Second New Army.(10) There were also three Home Service Divisions,(11) two divisions raised in the field in Egypt,(12) and the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division. The men who were chosen to command these divisions are key figures in any understanding of the British army's performance during the war. They have received scant investigation.

The British army's 84 divisions were commanded by a total of 222 men.(16) One-hundred-and-sixty-four commanded only one British division.(17) Forty-four commanded two divisions. Eleven commanded three divisions. Two commanded four divisions.(18) One commanded five divisions.(19) These numbers are indicative of the substantial turnover of commanders. Older men who were 'dug out' of retirement in the early part of the war, when the rapid expansion of the army made it difficult to find officers of sufficient seniority to command divisions, were replaced by younger men from 1915 onwards.(20) The attrition rate of commanders was also quite high. Nine were killed in action or died of wounds.(21) A further six were wounded.(22) A larger number still fell ill, were incapacitated, injured or invalided.(23) There was also the inevitable winnowing effect of the war's professional challenge. This resulted in a number of promotions. Forty divisional commanders went on to command a corps. Six became Army commanders. (24) Five became commanders-in-chief.(25) Others were less successful and many were 'degummed'. This resulted in the rapid promotion of younger officers who had demonstrated on the field of battle, as battalion and brigade commanders, their ability to command.

At this early stage of the research three things stand out. First, the extensive experience of active service accumulated by pre-war regular officers. Second, the numerical dominance of infantry men as divisional commanders. Third, the significant drop in the ages of divisional commanders on first appointment during the course of the war.

The pre-war British army was essentially a colonial police force. This is 23 usually accounted a source of weakness, which made it difficult to deal with the challenge of fighting the German army on the Western Front. It produced an army that fought in 'penny packets' at the battalion level or even lower, lacking in operational doctrine, weak in staff officers and undergunned in heavy artillery.(26) This is undoubtedly true, but there is another factor about the pre-war army to consider. The wars of empire produced an officer corps with vast combat and active service experience. The impression which emerges from looking at them, is not one of professional somnolence, but of an energetic and experienced group of men. Here are three examples from many.

When the war broke out Major-General C.G. Blackader was the 45 year old Commanding Officer of the 2nd battalion of the Leicestershire Regiment, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. He had served with the West African Frontier Force, taken part in operations on the Niger and the expedition to Lapia. During the South African War he fought at Lombard's Kop, in the defence of Ladysmith, at Lalng's Nek and in the Transvaal.(27)

Above: Major-General C.G. Blackader

In August 1914 Major-General Neill Malcolm was a 45 year-old Major in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. He had served on the North West Frontier and in Uganda. During the South African War he was severely wounded at Paardeburg. Later, he saw special service with the Somaliland Field Force, accompanied the British Mission to Fez, acted as Secretary to the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence and became a Staff Officer at the Staff College, Camberley.(28)

Above: Malcolm pictured in 1930 (National Portrait Gallery)

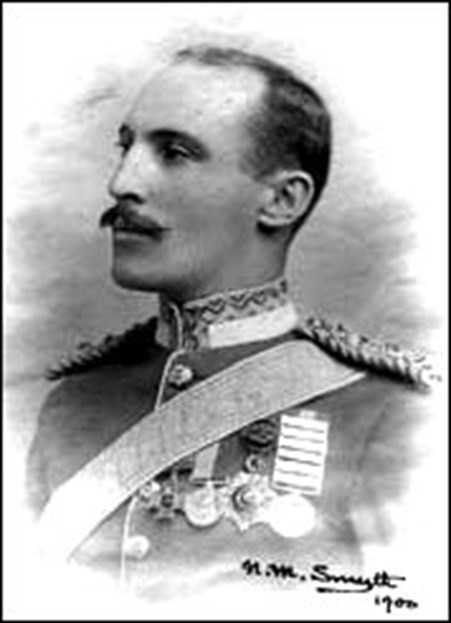

Major-General N.M. Smyth, who commanded the 2nd Australian and 29th (2/North Midland) divisions during the war, first saw active service in the Zhob valley in 1890, two years after he entered the army. He served in the Dongola expedition of 1896, including special service with the intelligence department. He was orderly officer to the OC Mounted Forces in the Battle of Firket. After the occupation of Dongola, he rode through the retreating Dervishes with a despatch to the Sirdar. He served in the Sudan in 1897, commanding both infantry and machine guns, and was severely wounded at the Battle of Khartoum, where he won the Victoria Cross. He later suppressed the Khalifa Sherif's rising on the Blue Nile, surveyed the Sudan and charted the Nile cataracts. He served in the South African War in Lawley's Column. In 1913 he found time to obtain his Aviator's Certificate.

Above: Major-General N.M. Smyth

This intensity and range of political-military activity ought to have been an asset to an army, providing it with men who were fit, adaptable and capable of command. However, it is usually dismissed as irrelevant to 24 the conditions which obtained on the Western Front. I find this difficult to understand. In the bureaucratic and lethargic French army it was precisely those officers who had seen colonial service who came to the fore during the war. The significance of the British army's colonial experience needs to be evaluated and related to the changes which took place among its divisional commanders between 1914 and 1919.

A commonplace explanation for the alleged inadequacies of British generalship during the Great War is that 'all the generals were cavalry men' imbued with something called a 'cavalry mentality'. Support for this accusation has been found in the fact that both commanders-in-chief on the Western Front and three army commanders were cavalrymen. There is no support for it at divisional level. One hundred and forty five (65.3 per cent) of the men who commanded divisions during the course of the war were infantrymen; only 29 (13.1 percent)were cavalrymen; 29 (12.6 per cent) artillerymen; and 12 (5.4 per cent) engineers. The rest were made up from the Indian Army, New Zealand forces and the Royal Marines. Ten of the cavalrymen commanded only cavalry divisions.(29)

These proportions were generally maintained during the war. Of the 72 men commanding divisions at the war's end, 47 (65.3 per cent) were infantrymen, nine (12.5 per cent) cavalrymen, ten (13.9 per cent) were artillerymen, and seven (9. 7 per cent) engineers. There were also two commanders from the Indian Army.(30)

If we look more closely at the regimental backgrounds of the infantrymen commanders, there are some surprises. In 1914 there were 69 infantry regiments of the line in the British Army. Fifty-six of these (81.2 per cent) produced at least one divisional commander. It is commonplace now for the British Army to be regarded as a 'Green Jackets' mafia'. The figures on the Great War provide some support for this. The infantry regiment of the line which produced most divisional commanders - nine (4.1 per cent)-was the King's Royal Rifle Corps (60th Rifles). This figure is more impressive if the numbers from the regiments which were amalgamated with the King's Royal Rifle Corps (in 1966) to produce the modern Royal Green Jackets (the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and the Rifle Brigade) are added. This gives another nine, making a total of 18 (8.1 per cent).

Other figures are less predictable. The Prince of Wales Own (West Yorkshire) Regiment produced five divisional commanders, only one fewer than the Coldstream Guards, the Grenadier Guards and the Royal Fusiliers. The Cameronians also produced five. Among the 72 men commanding a division at the war's end, 30 infantry regiments of the line (43.5 per cent) were represented, the West Yorkshire Regiment, the King's Royal Rifle Corps and the Cameronians coming 25 joint top with three each, a figure equalled by the Coldstream Guards.

'Looking round the faces opposite me,' Field-Marshal Haig confided to his diary on 20 July 1917, 'I felt what a fine hard-looking determined lot of men the war had brought to the front.' There is support for this view in an analysis of the age profile of divisional commanders. The age range of divisional commanders appointed during the war was enormous: from 69 to 35, with an average on first appointment of 51.5.(31) The age range of commanders appointed to Territorial divisions pre-war was 53 to 57, with a mean of 55.2. In 1914 the age range was 44 to 68 (mean of 52.8).(32) In 1915 43 to 69 (mean of 52.8). In 1916 41 to 59 (mean of 49. 7). In 1917 39 to 54 (mean of 58). In 1918 35 to 56 (mean of 45.9). Between 1914 and 1918the mean age of divisional commanders on first appointment thus dropped by a decade (from 55.2 to 45.9).

Of the divisional commanders appointed in 1918 23 (82.2 per cent) were under 50; ten (37 per cent) were under 45; and four (14.8 per cent) under 40. The ages of the 72 men commanding a division at the war's end ranged from 36 (Bethell) to 56 (Gorringe, GOC 4 7th (2/London) Division). 43 (59. 7 per cent) were under 50.

The extent of these changes is emphasised if we also look at rank. Of the 222 men who commanded a division during the Great War only 13 did so in the rank of Brigadier-General. A further five commanded divisions in the rank of Lieutenant-General. The rest were either substantive or temporary Major-Generals. The interesting word is 'temporary'. Of the 72 men who were commanding a division at the war's end, only one (Gorringe) was a substantive Major-General when the war broke out.(33)

Above: Maj-Gen George Gorringe

Of the rest, 20 (27 .8 per cent) were substantive Colonels, 19 (26.4 per cent) were substantive Lieutenant-Colonels, 22 were substantive Majors (five of whom were Brevet or Temporary Lieutenant-Colonels and one of whom had retired in 1911), nine were only substantive Captains (one of whom was a Brevet Major and another of whom was a Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel). By the end of the war a further 32 (44.4 per cent), mostly the pre-war substantive Colonels, had risen to the substantive rank of Major-General. Eleven (15.3 per cent) were substantive Colonels (Temporary Major-Generals). Thirteen (18.1 per cent) were substantive Lieutenant-Colonels (Temporary Major-Generals), eight of whom held the rank of Brevet Colonel). Thirteen were still only substantive Majors (Temporary Major-Generals) (nine of whom held the rank of Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel ,one of Brevet Colonel and one of Brevet Colonel, Reserve of Officers). One (Bethell) remained a substantive Captain (Temporary Major-General) (holding also the ranks of Brevet Major and Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel). Bethell did not become a 26 substantive Major-General until 14 June 1930.

Above: Hugh Keppel Bethell (National Portrait Gallery)

The most spectacular rise during the war, however, was not that of Keppel Bethell, but of the virtually forgotten Cyril Blacklock. Blacklock was born in 1880. He was commissioned into the 4th battalion of King's Royal Rifle Corps, from the 1st Warwickshire Militia, in 1901 and served in the Orange River Colony during the South African War. He made little impression on his regiment and in January 1904 he resigned his commission to settle in Canada. When the war broke out he returned to England. He was commissioned into the 10th (Service) battalion of his old regiment in November 1914 with the rank of Captain. Within a year he was its second-in-command. On 27 October 1915 he became CO. He fought in the Somme battles and was wounded at Guillemont in September 1916. On 18 January 1917 he assumed command of the 182nd (2/1st Warwick) Brigade in the 61st Division. He later commanded the 97th Brigade (32nd Division). In March 1918 he took command of the 9th (Scottish) Division. During the great battles of 1918 he commanded this division and then the 39th and the 63rd (Royal Naval) divisions in heavy fighting. He was then 37. He thus rose during the war from civilian (Lieutenant, retired) to Major-General.(34) His career fits uneasily into the traditional portrait of the British army's officer corps. This is a subject to which I shall return.

J.M. Bourne, University of Birmingham

The article has been lightly edited (and images of some of the individuals mentioned have been added) for the purposes of its (2019) republication

- The change was inaugurated by S. Bidwell and D. Graham, Fire Power. British Army Weapons and Theories of War 1904-1945 (1982), which remains an important book

- See, in particular, T. Travers, The Killing Ground. The British Army, the Western Front and the Emergence of Modern Warfare 1900-1918(1987) and How the War Was Won. Command and Technology in the British Army on the Western Front 1917-1918 (1992)

- See T. Lupfer, The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Changes in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: US Army Staff College 1981) and 8.1. Gudmundsson, Stormtroop Tactics: Innovation in the German Army, 1914-1918 (New York, 1989)

- R. Prior and T. Wilson, Command on the Western Front. The Military Career of Sir Henry Rawlinson 1914-1918 (Oxford, 1992)

- F.W. Berry has calculated the number of divisions which should prudently have been raised during the war on the basis of a 'divisional slice' of 60,000 men (15,000-20,000 fighting strength, plus a further 40,000 to keep the division in the field) divided into the number of men available aged 20-25 (this is the age group on which the burden of combat principally falls without doing too much damage to the civilian war economy). His figure comes out at a British Army of 28 divisions. On 11 November 1918 there were 54 British divisions on the Western Front alone. F.W. Perry The Commonwealth Armies. Manpower and Organisation in Two World Wars (Manchester, 1991) p 228

- The Guards Division, the 1st-8th Divisions and the 27th-29th Divisions

- The 42nd-56th Divisions

- The 57th-69th Divisions

- The 9th-26th Divisions

- The 30th-41st Divisions

- The 71st-73rd Divisions

- The 74th and 75th Divisions

- This number refers to those men who were in 'permanent' command of a Division. It does not include those who held 'acting' or 'temporary' command.

- Alderson (1st Canadian). Barrow (1st Indian Cavalry), Blomfield (1st Peshawar), H.D. Fanshawe (1st Indian Cavalry and 18th Indian), Gorringe (6th Poona and 12th Indian), Jacob (7th Meerut), Lipsett (3rd Canadian), Nugent(7th Meerut), Pilcher (Burma Division), Scott (8th Lucknow), Smyth (2nd Australian), H.B. Walker (1st Australian) and Wallace (11th Indian) commanded Dominion or Indian divisions as well as British.

- Major-General G.T. Forestier Walker, GOC 21st Division (11 April 1915-18 Nov 1915), 63rd Division (3 February 1916 - 21 July 1916), 65th Division (9 September 1916 - 11 December 1916), 27th Division (22 December 1916-end of war) and Major-General H.J.S. Landon, GOC 9th Division (21 January - 9 September 1915), 33rd Division (16 September 1915 - 23 September 1916), 35th Division (23 September 1916- 9 July 1917), 64th Division (14 August 1917 - 28 March 1918).

- Major-General C.J. Mackenzie, GOC 51st Division (3 March 1914 - 23 August 1914), 9th Division (27 August 1914 - 11 October 1914), 3rd Division (15 October 1914 - 29 October 1914), 15th Division (15 December 1914- 15 March 1915), 61st Division (4 February 1916 - 20 May 1918; 28 May 1918 - 31 May 1918).

- The fate of the 'dug outs' will be the subject of a subsequent article. That of one of them was tragic. Major-General R.G. Kekewich, who distinguished himself in the defence of Kimberley during the South African War, was called out of retirement to be the first commander of the 13th (Western) Division. On 26 October 1914 he was relieved of his command. Ten days later he shot himself in the head. The inquest recorded that he was depressed at being unable to serve his country. A verdict of 'suicide whilst temporarily insane' was recorded (Times, 7 November 1914).

- Broadwood (57th Division), J.E. Capper (7th), Feetham (39th), H.I.W. Hamilton (3rd), lngouville-Williams (34th), Lipsett (4th), Lomax (1st), Thesiger (9th) and Wing (12th)

- Baldock (49th Division), Bridges (19th), H.R. Davies (11th), Jacob (21st), Mackenzie (61st), Malcolm (66th), Paris (Royal Naval), Ritchie (11th). T. Capper (7th) was wounded then killed

- The Official History Order of Battle of Divisions is very careful in distinguishing the categories of 'sick', 'incapacitated', 'injured', 'invalided' and 'hospitalised'. Is there some subtle code at work here?

- Allenby, Byng, Gough, Horne, Monro and Rawlinson

- Allenby, in Egypt; Maude and W.R. Marshall, in Mesopotamia; Milne, in Salonika; and Monro, on Gallipoli and in India

- See, for example, D. Graham, 'Sans doctrine: British Army tactics in the First World War', in T.H.E. Travers and C. Archer,(eds), Men at War (1982), pp 69-92

- Blackader commanded the 38th (Welsh) Division from 12 July 1916 until 22 October 1917, and from 22 November 1917 - 20 May 1918, when he fell ill

- Malcolm commanded the 66th (2/East Lancashire) Division from 22 December 1917 until he was wounded on 29 March 1918. He later commanded the 39th Division from 10 September 1918 until 27 December 1918. He is better known as General Gough's acerbic Chief of Staff at Fifth Army, a role for which he has had a t.ad press. He is an interesting man, one of the few divisional commanders with a significant post-war career outside the army

- Of these, Alderson commanded a Canadian infantry division; Allenby and Byng went on to command a corps and then an army, Chetwode to command a corps

- Major-General G. De S. Barrow (Yeomanry Mounted Division) and Major-General P.C. Palin (75th Division)

- The oldest divisional commander appointed during the war was Brigadier-General H.B. MacCall (GOC 59th (2/North Midland) Division, 6 January 1915 - 14 November 1915). MacCall was 70 on 15 August 1915. The youngest was Major-General H.K. Bethell (GOC 66th (2/East Lancashires) Division, 31 March 1918- end ofthe war). Bethell commanded a brigade at 34 and a division at 35. There is a warts-and-all portrait of him in B. Bond and S. Robbins (eds) Staff Officer. The Diaries of Walter Guinness (First Lord Mayne), 1914-1918 (1987)

- The 44 year-old was Hubert Gough. Gough's youth has often been remarked upon. It stands out quite remarkably from this analysis, not only at the level of divisional command, but also at corps and army level

- Sir George Gorringe was the army's senior Major-General. All the corps commanders under whom he served were junior to him in service. His own advancement was said to have been held back by the hostility of Haig. See Nigel Hamilton, Monty. The Making of a General 1887-1942 (1981), p 135. Bernard Montgomery was Gorringe's Chief of Staff at the 47th (2/London) Division

- I am grateful to Major T.L. Craze (retd), Archivist of the Royal Green Jackets Museum, Winchester, for information on Blacklock's career.