Different Truths from the Same Battle

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Different Truths from the Same Battle

As dawn broke on the morning of 6 May 1915, the men of the 1/6th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers became the first British Territorial Army unit into action at Gallipoli. Although the number wounded was high, the fatalities from the first encounter were low. What is striking is the very different tone of the first-hand accounts recorded within just days of the fight…

The historian Edward H Carr wrote:

“History is not unlike a mountain in that it can appear very different depending on which angle it is viewed from.”

Carr’s statement was to prove more than prophetic during research I undertook into this battalion of the 42nd (East Lancashire) Territorial Army Division. Different men had different ‘truths’, and it soon became clear that a wide variety of factors would come into play.

When the 1/6th LFs scrambled from their front-line trenches at Gully Ravine that morning to take part in the Second Battle of Krithia, most of them had barely had any sleep - they had only arrived on the peninsula the afternoon before and then endured a night march, under fire, to their present position.

Above: Gully Ravine, Gallipoli. This photo shows soldiers of a Gurkha battalion of 29th (Indian) Brigade moving through Gully Ravine on 8 June 1915 (IWM: HU 105665)

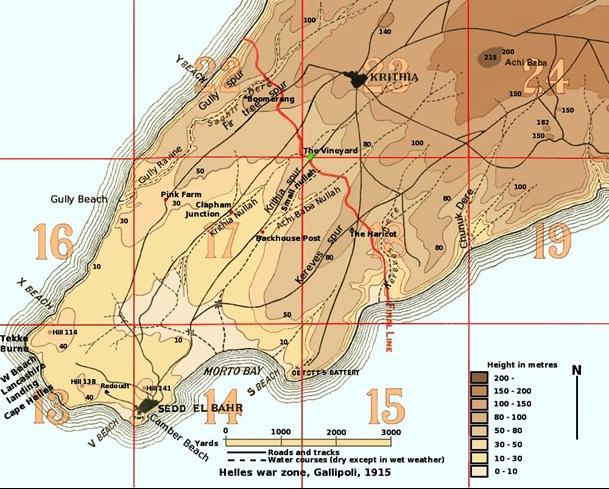

Above: Gully Ravine (in squares 17 and 22) was a natural feature on the west side of the peninsula

There had been no time to reconnoitre their own position, let alone the enemy’s, and their supplies (from food to cables for field telephones) had yet to reach them.

By early evening, after intense fighting, the CO, Lord Rochdale, pulled the 1/6th out of the line. He said that there were few men of the battalion left and these were now ‘done’, whilst most of the wounded were still out of reach in no-man’s land.

Above: Lord Rochdale, the commanding officer of the battalion.

Above: Officers of the battalion taking some time out – one reading a copy of Punch magazine.

Soon after accounts were being written in letters home and in diaries. Here are the accounts of a number of those present:

Captain Arthur Spafford was the adjutant and only professional soldier in the battalion. A veteran of the Boer War, he was described as everything you would expect of a British Army officer – a fan of hunting, shooting and polo who was feared, liked and respected in equal measure. Spafford wrote of the May 6 attack: “Well, now for our news. I cannot say very much as news is always so exaggerated... we have had a show or two and really did very well in our little sector of the fight. We lost a few casualties but one is bound to do that in a fight. Everyone behaved well and pluckily.”

Above: Captain Arthur Spafford is seen reclining in the desert in Egypt prior to embarkation for Gallipoli.

2/Lt Eric Duckworth, a teenager who had only joined the battalion after war broke out, penned the following of the same attack: “I was fortunate to come out unhurt but my platoon suffered. I cannot go into detail as regards numbers of casualties but 12 per cent are killed. We have had our fill of war and I shall not mind when it is over.”

Above: Teenager Eric Duckworth is pictured larking in civilian outfit and boater astride a donkey in Egypt.

Duckworth’s friend 2/Lt Norman Holden, a history teacher, recorded the following: “I was constantly thinking how I should behave under fire. I was almost more afraid of making a show of myself than getting killed, for make no mistake about it, I was afraid, horribly afraid, as every officer and man was.”

Above: History teacher 2nd Lieutenant Norman Holden in formal pose prior to leaving for the East.

It is worth noting that Spafford was writing to his new wife who had crossed the Mediterranean to Cairo just weeks before for a wedding attended by her husband’s fellow officers (many of whom were now seriously wounded). Spafford was maintaining the expected stiff-upper-lip, and not worrying his new bride in the process. He would be killed two months later at the Krithia Vineyard.

Duckworth was writing to his father: his extensive correspondence with different family members is most insightful – he generally paints a far more fraught and desperate picture in letters to his father than he does in letters to his mother and younger siblings. Less than a week earlier he had written in fear that the war would be over before they had had the chance to take part, and here he is after the horror of their first attack saying that they have now had their ‘fill’. Duckworth would also be killed at the Krithia Vineyard. His belief that 12 per cent of the battalion had been killed is probably a sign of his inexperience – this is more likely to be the number of wounded, as only a handful of men from the 1/6th died on the battlefield on that first day.[1] Most of these have no known grave and are commemorated on the Helles Memorial, however one - Frank Barker of Todmorden has a 'special memorial' within Twelve Tree Copse Cemetery.[2]

Above: Twelve Tree Copse Cemetery.

Norman Holden’s account is part of a private memoir/diary that he maintained from the outbreak of war until his death a few week’s after this first attack. The diary was clearly never meant to be read by others and is, as such, a very personal account that he would not have wanted his peers to see. Much of the content, particularly in relation to his fellow officers, could have seen him court-martialled.

Three very different accounts from three men from the same officers’ mess, all writing to very different audiences. Below are yet more accounts from the battalion that provide an even more nuanced picture, and vital insight into the dangers of accepting one version of history and failing to take into account the context of who is writing and to whom.

Major Heywood: “In the first day’s fighting all the officers were splendid. The CO, Lees and Spafford bored charmed lives and walked about as if on parade.” Heywood was writing an open letter to the local newspaper back home.

Lance-Corporal Ward: “Our battalion made a brilliant show. The men were laughing when they were going to their death.” Ward was writing to a friend back at home.

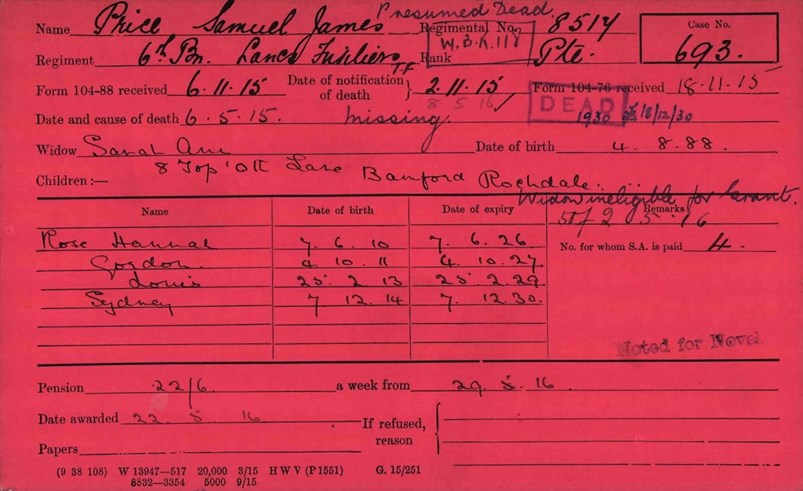

Above: A Pension Record Card for Samuel Price - he was one of those killed (the card details 'missing') as a result of the day's actions

Corporal Gerrard: “'Forward' was our motto. Though mates kept dropping we kept pushing on and inside a few hours we had them out of their positions. It was a great accomplishment and one which has earned a name for our battalion.” Gerrard was writing an open letter to workmates in the mill where he had previously been employed.

Private Charles Watkins: “There was no let up. To advance further was manifestly impossible. By unspoken mutual consent we dodged back... me inside a tiny cave. In the gloom were two soldiers of my own gang. One was sat up, his rifle pointed towards his own foot. In a tense voice, the bloke with the rifle pointed towards his foot said: ‘I’m going to get on that bloody hospital ship if it’s the last thing I do.’” Watkins was writing years later, as an old man, for a private memoir.

The official history of the 42nd Division: “The 6th Lancashire Fusiliers gained more than 400 yards before being held up by heavy fire... this was the greatest advance made by any unit that day, and the ground won was held.” This is all true.

Above: The Divisional history was not accurate in its depiction of the day’s events.

The official history of the Lancashire Fusiliers: “... the 1/6th had been leading the attack. It had to move over open ground where it met heavy shrapnel, machine gun and rifle fire. Although this was its first experience under fire, there was no wavering and it took its main objective.” The battalion did not get anywhere near its main objective and the claim that there was no wavering seems implausible – Charles Watkins’ account (above) certainly contests this.

Article submitted by Dr Martin Purdy

[1] The CWGC records five men of the battalion killed on 6 May, with another on 7 May

[2] It is of note that of the five men of the battalion killed, three were from the town of Todmorden, which is on the Lancashire/Yorkshire border.