Five into four does go

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Five into four does go

For his book, The Kaiser’s Battle, Martin Middlebrook did some analysis of the British Expeditionary Force’s (BEF) casualties on 21 March 1918, the opening day of the German Offensive. He estimated that about 21,000 men were reported missing that day, with more suffering a similar fate over the coming days as the offensive continued. Some downward adjustment of this figure needs to be made for those temporarily separated from their units and managed to rejoin in the following days, and also for those who were originally posted as missing but had either been killed or died of wounds. It is the stories of five men in the latter category that will be told in this article.

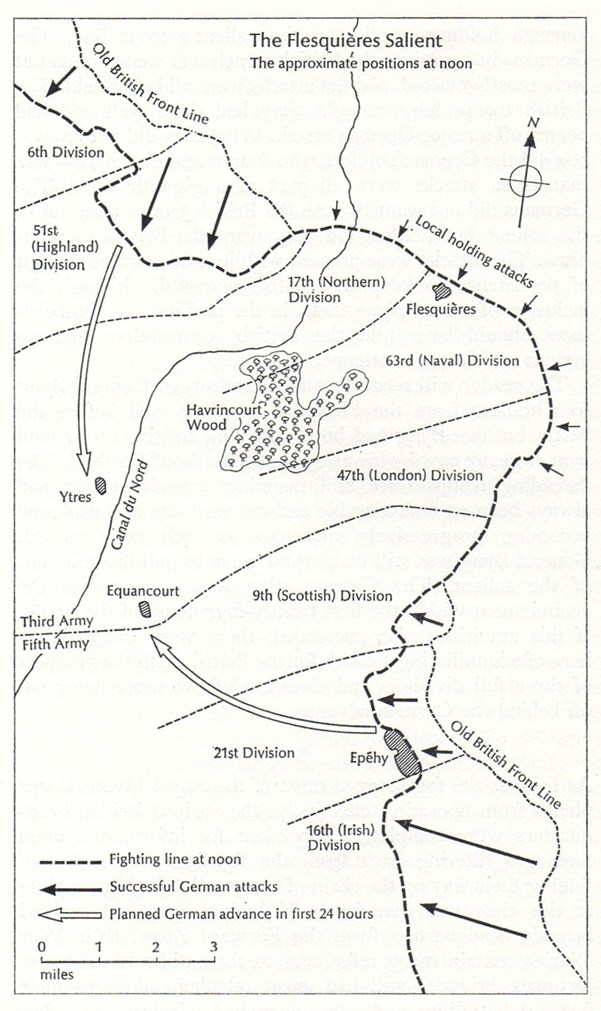

The 51st (Highland) Division was holding a sector of the front line on the northern flank of the Flesquières Salient. The salient was a legacy of the German counter-attack on 30 November 1917 that recaptured most of the ground gained by the BEF ten days earlier in the Battle of Cambrai. This salient, sticking out into German lines, was more difficult to defend and it is thought that Field Marshal Haig urged General Byng, commander of the Third Army, to withdraw his troops to a more defensible line, but he was reluctant to do so.

Above: The Flesquières Salient 21 March 1918. From The Kaiser’s Battle by Martin Middlebrook, 1978

At least to the north of the Flesquières Salient the BEF had been in possession of the ground for a year since the Germans retreated to the Hindenburg Line, and much effort had been put into the defences. The Highland Division had taken over the line astride the Bapaume – Cambrai Road at the beginning of December 1917 and, after initially occupying sections of the Hindenburg Line, they were withdrawn to a more defensible line in the old British Front Line on 5 December. This line was, however, soon found to be far from ideal for its new purpose and the Highlanders began a large programme of improvement.

By 21 March 1918 the line was strong and the Highlanders were in theory well-placed to fight off any attack. The story of the opening of the German Offensive is well known, particularly the thick fog which hampered both defenders and attackers, arguably the former more so. The opening artillery bombardment fell upon the Highlanders at 5 a.m., and after 7 a.m. concentrated on their left-hand brigade, the 153rd, and on the neighbouring 6th Division. This was due to the Germans not planning to attack the Flesquières Salient directly; instead they would try to drive in at the base on both flanks, ‘pinch it out’ and capture the trapped divisions. Only fifteen minutes into the bombardment almost all the Highlanders’ communications had been cut. The commanders’ first indication that the enemy infantry was advancing came at 9:53 a.m. when Second Lieutenants W.H. Crowder and J. Stuart, artillery observers in a forward position for the 256th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, reported to their HQ that men could be seen moving between the front and support lines. Two minutes later they confirmed that they were German infantry. At 10 a.m. their last message said that the enemy were all around them; both were taken prisoner and Crowder was later awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his exemplary conduct that morning.

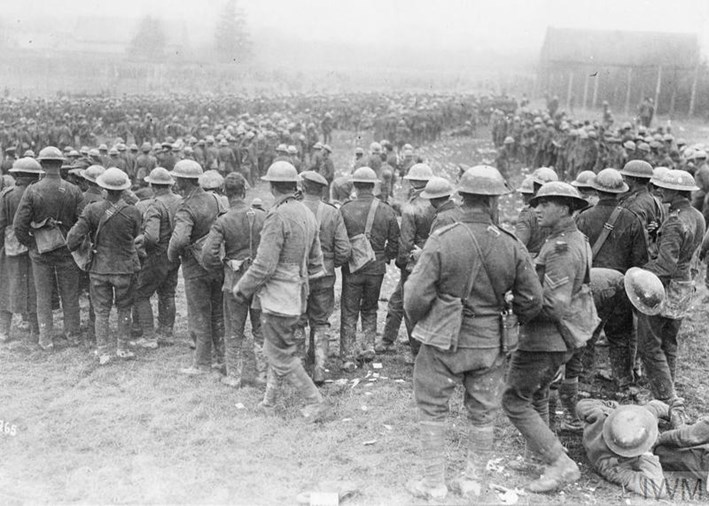

Above: Masses of British prisoners in a temporary PoW camp near Cambrai. IWM Q 24054

The battalions in the 6,000 yards of front line held by the Highland Division were,from right to left, the 4th Gordons; 7th Argylls; 6th Gordons; 5th Seaforth; 7th Black Watch and 6th Black Watch. With the recent reduction of divisional strength across the BEF from twelve to nine infantry battalions, this just left the 4th and 6th Seaforth and the 7th Gordons in reserve and available to man the Corps Line (the Beumetz – Morchies Line) if necessary.

For this article I will be looking particularly at the 7th Argylls, the 6th Black Watch and the 6th Seaforth, battalions from which five men were wounded and captured in the early stages of the German Offensive.

The 7th Argylls were south of the Cambrai Road near the village of Boursies and their War Diary records that the enemy entered the Highlanders’ trenches north of the road ‘in great force’ at about 9:00 a.m. and ‘proceeded to work to right and left, and down to the Cambrai Road. Boursies was entered at about 10:30 a.m. and Doignes shortly afterward. Enemy attacked our sector... bombing down the trench and using flammenwefer’. It records that the battalion’s mining platoon held up the enemy for some time but in the afternoon they, along with the rest of the battalion, were forced to withdraw to the reserve trench, where they remained until the following morning.

The 7th Argyll’sWar Diary records the officer casualties for 21 March as one missing, and one wounded. The missing officer was Lieutenant William Saville Johnston, who was captured by the Germans after being wounded in the right knee. He was taken to a ‘hauptverbandplatz’ (main dressing station)at Inchy-en-Artois, where he died on 23 March.William Johnston had only been in France seven weeks.

Above: A German field hospital at Inchy-en-Artois near the distillery - March 1918. Photo – Inchy-en-Artois en image Facebook page

Meanwhile, the 6th Black Watch had been fighting for their lives north of the Cambrai Road. Their plight can be gauged from a short report attached to their War Diary which says: ‘The last report from support line was that gas shelling was in progress. Nothing was known of what was happening in the front line’. Despite all posts being ordered to hold on, it soon became apparent that the brigade’s flanks were in danger and a withdrawal to the Beaumetz – Morchies Line took place.

The remnants of the 6th Black Watch continued defending the Beaumetz – Morchies Line on the 22nd, before withdrawing towards Bancourt in the early hours of the 23rd. An indication of the severity of the fighting can be found in the casualties reported for the month, almost all of them from the period 21 – 22 March: -

|

|

Killed |

Wounded |

Missing |

Totals |

|

Officers |

- |

5 |

15 |

20 |

|

Other Ranks |

17 |

78 |

494 |

589 |

|

|

17 |

83 |

509 |

609 |

Amongst these casualties were three wounded men who were captured and taken to Inchy-en-Artois: -

266699, Lance Corporal, William Hill McQuattie, who died on 25 March. Although his personnel file has not survived it can be deduced that he had joined some time before early 1917 (as he has four-figure and six-figure Territorial service numbers on his Medal Index Card) and had not arrived in France before the beginning of 1916 as he was not entitled to the 1914 - 15 Star.

266994, Private John Farquharson Duncan died on 25 March from a chest wound; his previous service appears to be similar to William McQuattie.

The following day saw S/21721, Private William Thomson, dying from a head wound. He also has two service numbers on his Medal Index Card having previously served with the Royal Scots. Like the other two men he was not entitled to the 1914 – 15 Star and therefore had not served overseas prior to 1916.

The 6th Seaforth were brought forward from reserve to man the Beaumetz – Morchies Line, but were not involved in any large-scale fighting on the 21st as the enemy were held about 600 yards short of the line and then had dug in for the night. The following morning, however, brought another artillery bombardment and further German infantry attacks. The 6th Seaforth, along with remnants of the other battalions forced to retire the previous day, fought off all attempts to dislodge them. They were ably supported by the guns of the 256th Brigade that were run out of their pits and fired over open sights at the advancing German infantry. However, by the end of the day, the Germans had worked their way past Beaumetz and Morchies and were threatening the Highlanders’ flanks, so they withdrew towards Velu and Lebucquière. On the morning of the 23rd the Germans advanced again, forcing another withdrawal towards Bancourt.

It is likely that it was on the 22nd or 23rd that Sergeant John Mackenzie was wounded and captured. He was also taken to Inchy-en-Artois, where he died on 25 March.

Above: Sergeant John Mackenzie MM and Bar, CdG, MiD, 6th Seaforth Highlanders

These five men were all buried by the Germans in a mass grave in the village cemetery, and at the time their identities were known. However, post-war when they were exhumed for reburial in Anneux British Cemetery, four of them were given named headstones but, for some reason, possibly a simple administrative error, one was buried as ‘unknown’.

Above: Anneux British Cemetery. Photo - CWGC

Ken Macdonald (great nephew of Sergeant Mackenzie) had known for some time that he was named on the Arras Memorial to the Missing, but had wondered why he was listed at the Scottish National War Memorial as ‘died’ rather than ‘killed in action’. He thought that he may have died of illness, but didn’t understand how if that was the case he did not have a marked grave.

In 2015 Ken and his wife Kath saw that some new records had been released on Ancestry and this included the Register of Soldiers Effects. She looked up John Mackenzie and his two brothers and in John’s case it was stated that he had died as a prisoner of war at Inchy-en-Artois, which she had never seen reference to before. The next stop was the archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross which produced an index card with three references to German records, one of which detailed that he had died in German field hospital at Inchy-en-Artois and was buried in a mass grave.

By sheer coincidence, the record above John’s was that of John Duncan who had been buried in the same mass grave. So Kath looked up John Duncan’s CWGC record and found the he had a grave at Anneux and, as she put it, “that got us really interested”. She wondered how could one have a named headstone and the other didn’t, when they’d both been buried in the same grave at Inchy-en-Artois. Further research revealed that the grave at Anneux was a collective one containing the remains of five men, four of whom were named and the fifth was ‘unknown’. Backtracking in the Red Cross records for the other three men revealed that they too had originally been buried in the same mass grave as John Mackenzie.

Ken and Kath Macdonald therefore thought that the fifth body at Anneux must be John Mackenzie, but to prove it required a massive effort to examine about 25,000 Red Cross records in case others had also been buried in the same mass grave. Having found no more they were now convinced that the fifth man must be John Mackenzie on the basis that five men, all named in German records, were buried together at Inchy-en-Artois and later exhumed and reburied together at Anneux in a collective grave, but somewhere in between the identity of one was lost.

Kath passed all the evidence to the CWGC, who forwarded it to the Ministry of Defence Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC),which subsequently agreed that the unmarked grave was that of John Mackenzie in the autumn of 2017. Through a lucky coincidence in the records, and thanks to Ken and Kath’s dogged determination, the grave of 21 year-old Sergeant John Mackenzie, MM and Bar, Croix de Guerre, MiD, had been found.

John Mackenzie came from Muir of Ord, Inverness-shire, but was living near Carrbridge in 1914 and when war was declared he travelled to Grantown-on-Spey and joined the Morayshire Seaforths. He went with the battalion to France on 1 May 1915 and fought with them on the Western Front for almost three years. He was twice awarded the Military Medal for bravery, the first at the Third Battle of Ypres in August 1917, and the second a few months later at the Battle of Cambrai. He was also awarded the French Croix de Guerre and Mentioned in Dispatches.

The CWGC engraved and erected a new headstone, and the JCCC arranged a rededication service for 27 March 2018, one hundred years and two days after John Mackenzie’s death.

When I learnt of the forthcoming rededication service, I contacted the family with a view to arranging a tour of the area fought over by the 6th Seaforth in March 1918, and I also contacted relatives of other 6th Seaforths killed in the battle. Consequently, my party were able to join John Mackenzie’s relatives in Anneux British Cemetery for the rededication service, with members of the Royal Regiment of Scotland also in attendance.

Above:27 March 2018, relatives of Sergeant Mackenzie, Major Johnston, Captain Stewart and Sergeant Edwards gather in Anneux British Cemetery after the rededication service. Photo courtesy of Danielle Roubroeks.

The relatives of Sergeant Mackenzie, MM and Bar, CdG, MiD; Major Charles Johnston, DSO, TD, commanding 6th Seaforth (killed, 23 March); Captain Weston Stewart (died of wounds in German hands, 27 March) and Sergeant Alexander Edwards, VC, (killed, 24 March) had been brought together, a most gratifying result.

Above: Captain Weston Stewart (courtesy of David Stewart); Sgt Alexander Edwards, VC, and Major Charles Johnston, DSO, TD.

Article by Derek Bird

Chairman North Scotland branch, The Western Front Association

Further reading:

The Kaiser's Battle by Martin Middlebrook - how accurate are the statistics?