Football in the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Football in the First World War

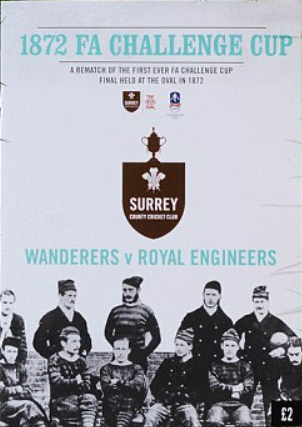

For the the 2021/2022 season, Saturday 14 May marks the playing of the FA Cup final, 150 years on from the first ever final between the Wanderers and the Royal Engineers.

Above: The Wanderers v Royal Engineers match programme - 1872

The result of the game will be important, not only to the supporters of Chelsea and Liverpool, but for millions of fans of English football around the world. The result of the 1915 FA Cup final was equally important as Gary Sheffield records ‘a soldier thought it essential to bring his officer news…during a tense moment in the second battle of Ypres’.[i]

Football has been embedded in British working class culture since the beginning of the early twentieth century. By 1915, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was essentially a citizen army, what John Bourne describes as the ‘British Working Man in Uniform.[ii] Football was, therefore, uniquely placed to maintain the morale of the British fighting man.

Above: British and French troops playing football behind the line at Ypres, February 1915. A row of soldiers can be seen in the foreground, sitting on the ground to watch the match. Photo – IWM Q 61558

The soldiers of the Great War found themselves having to live and work in surroundings that were, in very many ways, completely alien to them and induced a profound sense of dislocation. On the Western Front this would have included living in the trenches with their attendant mud, vermin and the nearness of death. To mitigate this almost overwhelming sense of dislocation and maintain morale, the soldiers sought to ‘evoke’ home, to create a bond of continuity with what they had left behind. Football played a key role in facilitating this continuity, was a breeding ground for primary groups and the vehicle for the inculcation of a sense of esprits de corps.

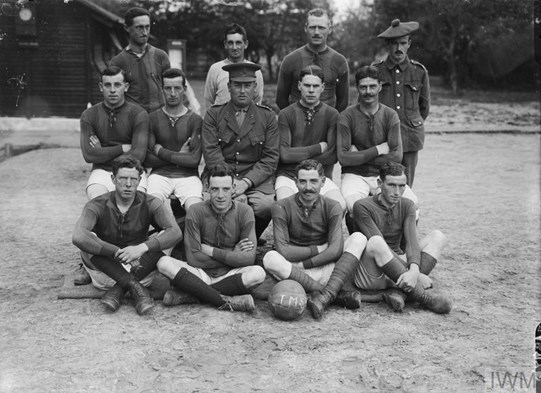

Above: the football team of the Third Army Trench Mortar School, St Pol (Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise), 20 May 1917. Photo – IWM Q 2481

Football also alleviated boredom. This was important as approximately 50 per cent of a soldier’s time on the Western Front was spent in billeting and rest areas.[iii] Playing football gave soldiers a sense of personal agency when much of what was supposed to be ‘rest’ was, in reality, work – transporting stores, mending roads, digging trenches.

The game was as ubiquitous at the front as it was at home.[iv] Both playing and spectating football allowed the transfer of common culture from a soldier’s local area. As in civilian life, sport provided an affirmation of community. It was played in Mesopotamia as well as France and Belgium; ‘platoon, company and battalion football matches were played, ten minutes each way at 110 degrees in the shade.’[v] Football was used to promote esprit de corps. Two thousand five hundred troops attended the inter-battalion final of the 48th Division’s Fanshawe Cup.[vi] The anticipation of a big match, talking about the match both before and after, could all help to maintain the morale of both the individual soldier and his primary group. Moreover, football was an area of autonomy away from rigid discipline, allowed for the displacement of real anxiety and provided excitement innocent of fear.[vii]

Above: Final of the 48th Divisional (Fanshawe) Cup. 1/7th Battalion, Worcestershire Regiment versus 1/7th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment played at Trissino, April 1918. Photo – IWM Q 26357

As previously stated, by 1915 the BEF was a citizen army increasingly dominated by the battalions of Kitchener’s New Army. Here, the omnipresent football was a fertile breeding ground for primary groups. Writing to the Bedfordshire Times & Independent, 12801 Sergeant Fred Blakeman of the 7th(Service) Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment, referred to as the ‘well known footballer’, states:

There are several well-known footballers in this Battalion and among those you will know best are Sergeant Joe Ginger of Leighton Town, Pte Ansell, Luton Clarence, Pte Wildman of Riseley, George Green, late of the Queen’s Park Rangers and Falcons and Sid Poole. They are not all in my company but we see each other very often and talk over old times and battles we have fought in different circumstances.[viii]

As noted in the above letter, Sergeant Blakeman was also known to 12790 Lance Corporal Sidney Poole. A letter written by Poole to a friend in Kempston was published in the Ampthill & District News and stated ‘Blakeman told me he had written you the other day. I don’t often see him (Blakeman) as he is serving with B Company but when we do meet it means a good hour’s ‘confab’.[ix]

In the Yarmouth Mercury, 3/10402 Sergeant Samuel Godfrey, of the 8th (Service) Battalion, Norfolk Regiment (8th Norfolks), writes regarding ‘his next-door neighbour’, Sergeant Mickey Thornton, who was formerly Hon. Secretary of Yarmouth Town Football Club.[x] In an earlier edition of the same newspaper, Sergeant Thornton himself writes:

I see plenty of the footer men of Norfolk here. Bullen and Little of the C.E.Y.M.S are sergeants, as also is Jefferies of Cromer and lots of others so we have plenty to talk about old times. Next to me at this moment is Sergt Packer of Clapton fame who never tires of telling me how they were summarily dealt with after beating Town at the Recker and also how we met our doom at Spotted Dog in the memorable cup tie.[xi]

Lance Corporal Ernest Ames, who joined the 8th Norfolks in July 1916 as part of a draft to rebuild the Battalion after the devastation of the first day of the Somme battle, also knew Sergeant Thornton. The headline captioning his letter to the Yarmouth Mercury describes Ames as ‘the well-known Town Football Club left-winger’[xii]

These letters demonstrate that football would have provided common currency amongst fellow NCOs and amongst NCOs and the men under their command. The transposition of those local sporting and community networks gave NCOs social capital that they could use to shape and direct the citizen soldiers in their care and buttress their morale. Moreover, this relationship was two-way; the men they commanded had common ground in which to engage with their superiors, the men who controlled their lives.

Football was not limited to the New Army battalions. For one of the first Territorial regiments deployed to France, 1/14th (County of London) Battalion, London Regiment (London Scottish), there is evidence that football was used as a tool for creating community in the years before war broke out. The Regimental Gazette records details of the Regimental Football Club and the tradition was carried to France; ‘soccer between officers and sergeants in the afternoon’ records 1840 Lance Sergeant Arthur Davidson.[xiii]

Above: Troops of the 1st Battalion, Wiltshire Regiment, football near Bouzincourt, Sept. 1916. Photo IWM Q 1109

However, not everyone was convinced of the benefits of football. In 1915, in response to an increase in the number of cases of men asleep on duty (a crime potentially punishable by death), General Haig, then commanding First Army, wrote in his diary ‘men should rest during the day when they know they will be on duty at night. Instead of resting they run about and play football’. By 1919, Haig appeared to have changed his mind. In his Rectorial address to the University of St. Andrews he eulogised team games ‘…promoting discipline and unselfishness among the lead and initiative and self-sacrifice among all’.[xiv]

The sheer tenacity of the soldiers of the BEF was a major contributor to ultimate victory on the Western Front. Football was influential in maintaining morale by reinforcing soldiers’ coping mechanisms, building and strengthening primary groups and instilling a sense of esprit de corps in a citizen army.

Article by Stephen Manning

Further reading:

The Manchester United v Liverpool match fixing scandal of 1915

[i] G. D. Sheffield, Leadership in the Trenches Officer-Man Relations, Morale and Discipline in the British Army in the Era of the First World War (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan) p. 45

[ii] J.M. Bourne, Britain and the Great War 1914-1918 (London: Edward Arnold) p. 214

[iii] J. G. Fuller, Troop Morale and Popular Culture in the British and Dominion Armies 1914-1918 (Oxford: Clarendon Press)p. 59. 7th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment spent 42% of their service in the front line, 38% in billeting areas and 20% in rest areas. This pattern held from 1915 to the latter part of 1918 when front line service rose to 50%.

[iv] Imperial War Museum (IWM) Box no P239, Private Papers of Lieutenant W. B. St Leger MC. Lieutenant St Leger’s diary contains multiple examples of football played at platoon, company and battalion level in the Coldstream Guards. Matches against other formations such as the Royal Engineers are also recorded.

[v] Fuller, Troop Morale, p. 92

[vi] Ibid, p. 93

[vii] Ibid, p. 93

[viii] Bedfordshire Times & Independent, 5 November 1915

[ix] Ampthill & District News, 11 December 1915

[x]Yarmouth Mercury, 9 January 1916

[xi] Ibid, 9 January 1916

[xii] Ibid,30 September 1916

[xiii] London Scottish Regimental Gazette, No. 221, Vol. XIX (May 1914); London Scottish Regimental Museum: Diary of Lance-Sergeant Arthur G Davidson

[xiv] J. Terraine, General Jack’s Diary War on the Western Front 1914-1918 (London: Cassell & Co 1964 [2001]) p. 91