Friendly Fire: The Life and Death of Frank Downes

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Friendly Fire: The Life and Death of Frank Downes

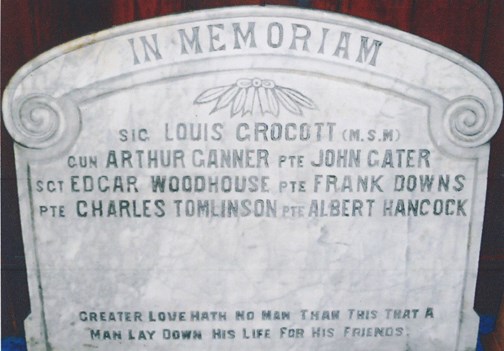

Paul Brant, who has done splendid work in recording and preserving memory of the Great War in North Staffordshire, recently sent me a photograph of the stained-glass windows war memorial of Longport Methodist Church in Stoke-on-Trent. While Paul was taking the photographs he spotted another memorial stone that had apparently been placed in the church for safe-keeping, but which had not originated there. No one at the time he took the photographs seemed to know where the memorial stone came from. He sent me a photograph of that, too.

Seven names are inscribed on the stone. Two of them immediately caught the attention of me and my collaborator Mick Rowson. The first was Charles Tomlinson. His was the only name on the memorial that had not been included on our Burslem roll of honour (Longport is a suburb of Burslem, the Mother Town of the Staffordshire Potteries). When we checked Tomlinson’s name in Soldiers Died in the Great War, it was immediately apparent why he had not flagged up as a ‘Burslem man’. His place of birth was stated as Flint (actually Moss, near Wrexham) and no place of residence at the time of enlistment was shown, but further research in the census records established that he was definitely living in Burslem before the war and we added him to the roll of honour. (More perhaps on Charles Tomlinson at a later date.)

Above: The industrial landscape of the potteries. This photo was taken in about 1940

The second name was that of Frank Downs [sic]. Historical research is about seeking out the past, but there are times when it feels as though the past is seeking out you. This is the way we feel about Frank Downes. This is his story.

Franklin Day Downes was born out of wedlock to Mary Elizabeth Downes, general servant, on 26 December 1896, at Swainby, a village in North Yorkshire.

Above: 'Entrance to Swainby'

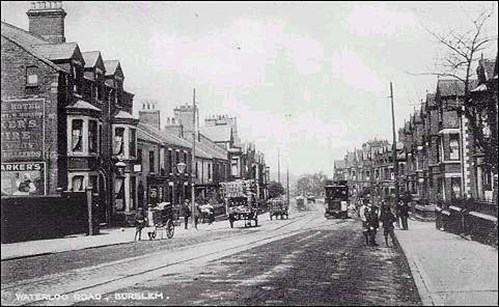

His grandfather, William Downes, was an ironworker, who migrated from the great iron town of Middlesbrough, first to Coseley, near Wolverhampton, and finally to Burslem. Although the area is most famous for ceramics, it was also important for coal and iron and steel. We first pick Frank up in the Census of 1901, living with his grandparents, William and Jane, at 11 Waterloo Road, Burslem, a property described as a ‘confectionery shop’.

Above and below: Waterloo Road then and now. Probably at the same spot.

The other household members were Mary Ellen (sic), daughter (29 and single), Arthur, son (19), Henry Levi, son(16), and Franklin, grandson (4).There is no indication in the official record that Frank knew who is mother was, even though he lived with her in 1901 at least. His Attestation Form gives his next of kin as his grand-parents. His grand-mother is shown as his legatee in the Registers of Soldiers’ Effects.

Mary Elizabeth Downes married in 1906 and went on to have two more children, Emma Jane and William. Emma was the name of one of her sisters and Jane the name of her mother. William was the name of her father. This suggests a strong sense of family that did not appear to extend to her first child.

Frank Downes volunteered for military service on 3 November 1915. His age was stated as 19 years 11 months, though he did not actually turn 19 until the end of December. His occupation was given as ‘potter’. He had evidently grown into a decent and rather serious young man. He was a member of several temperance clubs as well as of the Wilkinson PSE and PSA, an organization formed by Arthur Wilkinson, a successful potter and factory owner, that was intended to provide Pleasant Saturday Evenings [PSE] and Pleasant Sunday Afternoons [PSA] of uplifting and alcohol-free entertainment and instruction.

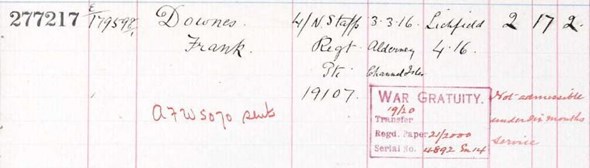

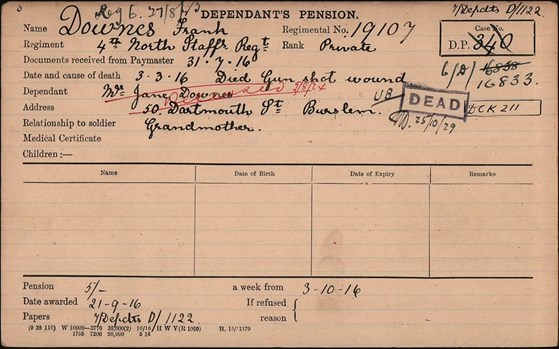

Frank was posted to the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, which had been based in the Channel Islands since August 1914. On 3 March 1916 he was shot and mortally wounded on the island of Alderney by another member of the battalion, Private Joseph Humphries.

Above: The Pension Record Card for Frank Downes giving his date of death of 3 March and that he 'died of a gunshot wound'.

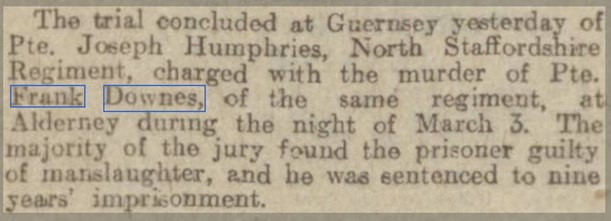

Humphries was tried for ‘wilful murder’ before the Bailiff of Guernsey and ten jurists, but found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to ten years’ penal servitude.

Sir Edward Chepmell Ozanne (1852-1929), KBE, Bailiff of Guernsey 1915-1922 by Mary Macleod (https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/sir-edward-chepmell-ozanne-18521929-kbe-bailiff-of-guernsey-19151922-136820)

Humphries’s case was helped by the absence of eye witnesses. Sergeant-Major Robert Beattie’s account of the incident was based on an exchange he had with Humphries after his arrest.

‘What have you being doing Humphries?’ the CSM demanded. Humphries replied that Downes had woken him, whereupon he said ‘Do you know what you are liable to get for leaving your post?’ [Downes had evidently been on night guard]. According to Humphries, Downes replied ‘I am liable to be shot, but you can’t shoot me’. Humphries then put a round in his rifle and fired!

Above: Several newspapers reported the case, in this instance the Aberdeen Press and Journal (dated 7 April 1916)

Humphries was only in place to kill Downes by mischance. The military authorities on Alderney had sent him to Guernsey some time before with a view to having him discharged from the army but had failed to supply the appropriate paperwork and he was returned to the battalion. You can understand why the army wanted to get rid of him. Humphries emerges from the trial evidence as something of a simpleton, a man who was ‘rather stupid’, ‘of low intellect’, who had not finished the musketry training course ‘and could not hit a miniature target at five yards’, in short ‘a fool’.

But there was a darker side to Joseph Humphries. He was a liar and a thief and no stranger to casual and irrational violence. It was the second time he had dodged the rope. In June 1913 he had been charged with ‘feloniously wounding’ Agnes Wilson, a woman with whom he had been living, ‘with intent to murder her’. He pleaded guilty to ‘wounding with attempt to do grievous bodily harm’ at Stafford Assizes the following month and the prosecution accepted the plea. The judge decided for reasons perceptible only to judges to take a lenient view of the case. Humphries was sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

Frank’s death was mourned back home and not just in his immediate family. On Sunday, 19 March, memorial services in his honour were held at the Wilkinson PSA and the Burslem Ragged School.

Above: The Ragged School. just off High Street, Burslem. The Ragged School was for destitute children

The services were attended by ‘a large number of friends’ and were of ‘an impressive character’. In 2002, with the Ragged School building facing imminent demolition, Roger Simmons, a friend of Mick’s, rescued Frank’s photograph and saved it for posterity.

I am not superstitious in normal life, but I am in my professional life. This was an omen. Frank wanted his story to be told.

Frank Downes is buried on the island of Alderney in St Anne’s Churchyard under a headstone erected by his comrades.

The wretch Humphries lived deep into old age.

Article by John Bourne and Mick Rowson

John Bourne taught History at Birmingham University for thirty years before his retirement in September 2009. He founded the Centre for First World War Studies, of which he was Director from 2002 to 2009, as well as the MA in British First World War Studies. He has written widely on the British experience of the Great War on the war front and the home front. He is currently completing a multi-biography of Britain’s Western Front Generals. He is a Vice President of The Western Front Association, a Member of the British Commission for Military History, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Hon. Professor of First World War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton.