From Bradford to Boulogne via Suvla Bay: The Great War Journey of Private 10915 Harold Wood, Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment

- Home

- World War I Articles

- From Bradford to Boulogne via Suvla Bay: The Great War Journey of Private 10915 Harold Wood, Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment

The city of Bradford in West Yorkshire has a rich history, from its origins as a settlement that dates as far back to at least the Anglo-Saxon era, to the Industrial Revolution which saw it become an important centre of the wool trade and textile manufacture. So much so that during the 19th century it became known as the ‘Wool Capital of the World’. Bradford specialised in the manufacture of worsted cloth, and consequently was nicknamed ‘Worstedopolis’ or, less frequently as ‘Woolopolis’, to rival Manchester’s ‘Cottonopolis’. The rapid growth of the industry attracted workers from near and far to toil in the mills that proliferated in the city and surrounding area. The sheer number of mills caused a dreadful public health problem, the factory chimneys belching out black smoke which contributed to the high infant mortality rate, particularly affecting the children of textile workers. The conditions that the workers themselves laboured under were grim, the work itself monotonous and arduous. It’s no surprise then that so many millworkers jumped at the chance to escape the drudgery, the dust and noise, upon the commencement of the Great War in 1914 and enlist.

Above: One of Bradford’s ‘dark satanic mills’ (Image – undercliffecemetery.co.uk)

One such millworker was Harold Wood, aged 20 and Bradford born and bred. Harold was a Woolcomber, a role that involved combing scoured wool to separate and straighten the fibres preparatory to spinning into worsted yarns. This was a mechanised process using a wool-combing machine.

Above: Wool combing machine (image – ecoworldonline.com)

Harold was born on 21 October 1893 in Bradford, Yorkshire, to Watson Wood and his wife Ann Jane Wood (née Bakewell). By the time of the 1901 census, Harold aged 8 was living at 19 Ashley Street, with his father Watson aged 43, his mother Ann aged 42, brothers Albert 23, Samuel 18, Ernest 15, Walter 12, Percy 5, and sisters Florence 23 and Lily 3. Ten years later, the 1911 census shows he was living with his older sister Florence and her husband George Pickup at 20 Surrey Street, Bradford, and employed at that time as a pit lad at a coal mine.

Harold enlisted shortly after the outbreak of war, attesting at Bradford on 21 August 1914, and joining the Duke of Wellington’s (DOW) West Riding Regiment at the Regimental Depot, Halifax, on 23 August 1914, being posted to the 8th Battalion. His personal details were listed as follows: Trade or occupation: Woolcomber; Complexion: Fresh; Eyes: Grey; Hair: Lt. Brown; Height 5’ 6 Weight 107lbs: Chest measurement when fully expanded: 34½ inches.

Above: Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding) Regiment’s Depot, Halifax (Image – dwr.org.uk)

The 8th Battalion were raised as part of Kitchener’s New Army, initially of the 34 Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division, before being transferred to 32 Brigade (also in the 11th Division) on the 18 January 1915. They completed training at Witley in April 1915 before sailing from Liverpool on the SS Aquitania for Gallipoli, on 3 July 1915.

Above: SS Aquitania (Image – ssmaritime.com)

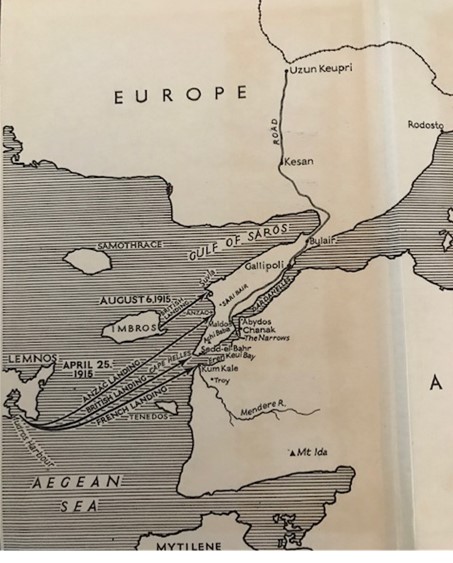

The campaign in Gallipoli had begun on 19 February 1915 but little progress had been made by the time Harold embarked from England nearly five months later. The voyage through the Mediterranean and Aegean was fraught with danger. Infested with enemy submarines, these underwater predators had to be avoided, and two protracted stays en route were taken, bivouacking on the Greek island of Lemnos and then the Turkish island of Imbros. Harold’s 8th battalion, along with the rest of the 11th Division, formed part of a substantial force tasked with a night attack on Suvla Bay, in an effort to drive the Turks off of the heights of the Sari Bair Ridge inland, neutralise the Turkish guns on Chocolate Hill, and establish a foothold for further offensives. It was decided that ‘The most suitable date, with darkness for the approach to the shore and moonlight for movement forward from the beaches, was the night of 6/7 August.’[1]

Above: Map of Gallipoli campaign, showing both the April and August landings (Image – from Alan Moorehead’s Gallipoli, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1956, endpaper)

At 4:30pm on the 6 August, Harold embarked from the island of Imbros for the last, short leg of the journey to Suvla Bay. The weather was glorious as they boarded the destroyers: ‘August 6 was a day of calm, hard, glaring sunshine, and in the afternoon when the soldiers were embarking at Imbros, they could clearly hear the roar of the guns at Anzac and Cape Helles where the battle had already begun. Bright little stabbing flashes sparkled in the sky. As night fell a few minutes after seven a brilliant crimson sunset expanded along the horizon. Then it was black darkness, with no light showing in the Fleet. The island with its thousands of empty tents and its silence took on an air of terrible desolation. ‘The day before the start is the worst day for a commander,’ Hamilton [General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander in Chief, Gallipoli Expedition]wrote. ‘The operation overhangs him as the thought of another sort of operation troubles the mind of a sick man in hospital.’ He was restless, and walked down to the beach to see the 11th Division go off. The men, packed like herrings in the beetles and on the decks of the destroyers, were silent and listless: ‘These new men seem subdued when I recall the blaze of enthusiasm in which the old lot started out of Mudros harbour on that April afternoon[referring to the 25 April Landings].’ For a moment he debated whether or not he should have cruised round the invasion fleet in a motor launch, saying a few encouraging words to each unit as he went along, but he dismissed the idea when he remembered that the men did not know him by sight; and in any case several hours were to go by before they arrived on the beaches, and that was too long an interval for his words to survive.’ [2]

Above: British troops landing at Suvla by X Lighters, 7 August 1915 (Image – xlighter.org)

Hamilton clearly felt powerless and resigned himself to waiting for news, for however long it took. Presently he ‘strolled down to the beach again and saw the ships moving, ghostlike and silent, to the boom across the mouth of the harbour. ‘This empty harbour frightens me,’ he wrote later. ‘Nothing in legend is stranger or more terrible than the silent departure of this silent army.’ Then he went back to his tent to keep a vigil with his telephones through the night.’ [3] Hamilton’s apprehension and sense of melancholy would prove to be prescient. Over the ensuing days, the offensive stalled. Chaos and confusion reigned, and golden opportunities to swiftly take all of their objectives with minimal casualties were missed, caused by indecisiveness and procrastination, and, it must be said, inept leadership. The dithering and delay, the failure to advance and capture the high ground and beyond, when it was eminently achievable, would cost them dearly.

Above: Troops landing on C Beach, Suvla Bay, later in the day, 7 August 1915 (Image – iwm.org.uk)

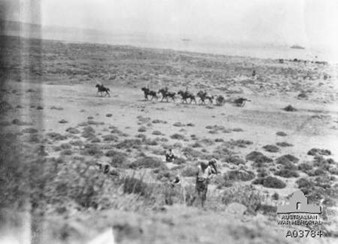

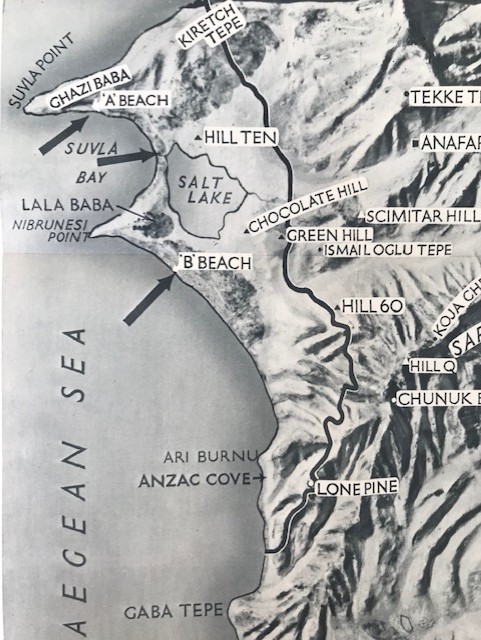

The 8th DOW, crammed onto the decks of a destroyer since 16:30, finally weighed anchor at 20:00, landing at Suvla Bay under fire around midnight, although the battalion’s war diary described the disembarkation as ‘landing unhindered at Suvla Bay’. Harold’s battalion moved off in support of the 6th Battalion Alexandra Princess of Wales Own Yorkshire Regiment towards Lala Baba. About 02:00 on 7 August they were ordered to cross the Salt Lake and assist in occupying Hill 10. The following day they moved up to support the 9th Battalion The Prince of Wales’s Own West Yorkshire Regiment on the line Sulajik-Kuchuk-Anafarta-Ova, and by nightfall were dug in alongside the West Yorkshires.

Image: A British field gun going into action behind Lala Baba after landing at Suvla Bay (Image – awm.gov.au)

Around 04:00 on 9 August, the 8th DOW, accompanied by the 67th Field Company Royal Engineers, were ordered to attack the heights of Tekke Tepe. At approximately 06:00 they were about 800 yards short of the objective, when the troops in the vanguard ‘appeared to be returning, so the order was at once given to advance to a small donga (a ditch or dry gully) and hold on there. By this time a lot of men from the leading regiment had rushed past saying that the Turks were advancing in force. The fire now became very hot and heavy casualties were rapidly being sustained.’ These casualties included both the CO and his second-in-command, and Captain Vivian Norval Kidd assumed command of the battalion. He wrote ‘The Turks were now beginning to turn my flanks and as I had only about 350 men left and practically no officers and ammunition was running short, I decided to withdraw to a more suitable position. At about 11:30 we took up a position near a farmhouse about 600 yards due west of the donga and took steps to hold on until reinforcements arrived and more ammunition. The enemy (about 500 strong) came on but were held for about an hour, until it was again reported to me that we were being turned on our left flank. At that moment, a runner came up from Headquarters 34 Brigade (a sister brigade to the 32 within the 11th Division)with an order saying that if compelled to withdraw I was to fall back on the left of the Manchester Regiment. This movement was completed by about 15:30 and we at once dug ourselves in on the left of the 34 Brigade.’ [4]

Above: Soldiers dug in at Chocolate Hill, Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, 1915 (Image – collection.nam.ac.uk)

The delay in attacking and taking the heights had proved catastrophic; ‘as the men in the leading company [of the 32 Brigade] went forward the Turks burst over the rise above them. It was a tumultuous charge, and it annihilated the British. Within a few minutes all their officers were killed, battalion and brigade headquarters were over-run, and men were scattering everywhere in wild disorder. In the intense heat of the machine-gun fire the scrub burst into flames, and the soldiers who had secreted themselves there came bolting into the open like rabbits, with the smoke and flames billowing out behind them. At sunrise Hamilton, watching from the deck of the Triad, was presented with an awful sight. His men were streaming back across the plain in thousands, and at 6am, only an hour and a half after the battle had begun, there seemed to be a general collapse. Not only were the hills lost, but some of the soldiers in their headlong retreat did not stop until they reached the salt lake and the sea. ‘My heart has grown tough amidst the struggles of the peninsula,’ he wrote in his diary that night, ‘but the misery of this scene wellnigh broke it…words are no use.’ [5].

Above: Suvla Bay Landings, showing the British Front Line at the end of August 1915 (Image – from Alan Moorehead’s Gallipoli, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1956, map facing p.352)

Undoubtedly it was during this action on 9 August 1915 that Harold was wounded, suffering a GSW to his left leg. The 8th DOW war diary details the day’s events as: ‘In action, heavy losses. Lt. Col. H.J. Johnston wounded and missing’[6]. Harold entered the medical chain of evacuation and was conveyed to the British army base at Mudros on the Island of Lemnos, where he received medical attention before sailing on the 10th for home, returning on the SS Aquitania bound for Southampton. Harold’s Army Form B178: Medical History (Table II, pages 2 and 3), details his admission to Alexandra Military Hospital, Cosham, Portsmouth, with a ‘GSW left leg’, before being transferred on 27 August 1915 to the Red Cross Hospital, Winchester for further treatment, to be finally discharged on 9 September 1915. The Remarks section of the report describes his wounds and the subsequent course of action: ‘Bullet through main part of popliteal space. No injury to bone, tendon, or nerve. Clean. To come home.’ This reveals how extremely lucky Harold was, the popliteal fossa is the space behind the knee between the thigh and calf muscles, with blood vessels and nerves passing through it, and he’d been fortunate enough to suffer a straightforward flesh wound: a highly prized Blighty one.

Above: Queen Alexandra Hospital, Cosham, Hampshire (Image – bygone.co.uk)

Following his discharge from hospital, he was granted leave to convalesce in Bradford. He made a complete recovery and was posted to the 11th Battalion DOW on 15 October 1915. By this time, the 11th had become a Reserve Battalion, and soon after Harold’s arrival they were transferred to Brocton Camp, Cannock Chase, Staffordshire in November 1915, eventually being absorbed into the Training Reserve of 3rd Reserve Brigade.

Above: Terrain Model - Brocton Camp. At the start of the Great War two large camps each housing 20,000 men were built on the open heathland of Cannock Chase. The camps had their own power station, roads and standard gauge railway. Training was carried out on a series of rifle ranges and practice trenches. The model in one of the original wooden huts gives an idea of the scale of construction carried out through the winter of 1914 with the first battalions arriving in April 1915 (Image – geography.org.uk ©John M)

The bleak uplands of Cannock Chase were owned by the Earl of Lichfield, and upon the outbreak of war he had granted the use of the land to the army. The landscape was now covered by ‘a vast, unbeautiful military complex [which] had been grafted on to the face of the heath where the Sher Brook ran off it northwards. On the shallow banks of the stream the army had established Rugeley Camp and its neighbour Brocton Camp, together big enough to process 40,000 men at a time. Grim barrack huts were arranged in straight parallel lines around a complex of parade grounds, above which loomed a square water-tower and a power station whose four chimneys pumped smoke into the sky […] the battalions of the 3rd Reserve Brigade trained here in musketry, scouting, physical training, gas warfare, and other disciplines, including signalling. Concerts and gatherings in cramped YMCA huts provided some social life for the rank-and-file soldiers, but escape was sought as often as possible in the pubs of villages around the Chase; boredom and drink, however, proved an inevitably fractious brew, and discipline was enforced with extra drills and fatigues, or confinement to the guardroom. The winter barracks were bitter with coke fumes and tobacco smoke, mingling oppressively with the smell of boot polish, sweat, beer, rifle-oil, and wet floors.’ [7].

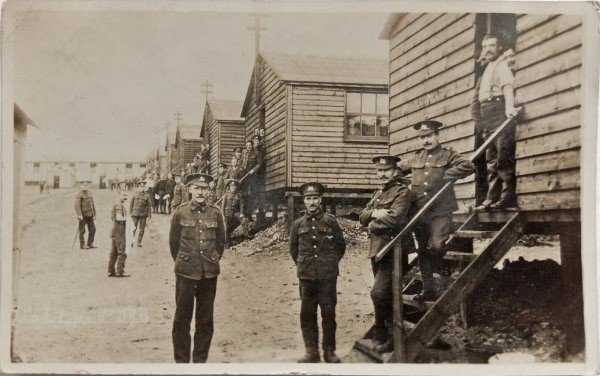

Above: Men of Brocton Camp, First World War (Image – WordPress.com)

The suffocating mixture of boredom and harsh discipline proved too much for Harold, and on the 1 December 1915 at around 9am he broke out of Brocton Camp and went on the run. His break for freedom didn’t last long, he was apprehended by the civil police at Crewe later that day, possibly intent on boarding a train. On 4 December 1915 he was sentenced to 10 days Confinement to Barracks and lost a day’s pay. Upon the expiration of his punishment, Harold was posted to the 10th Battalion DOW on 13 December 1915.

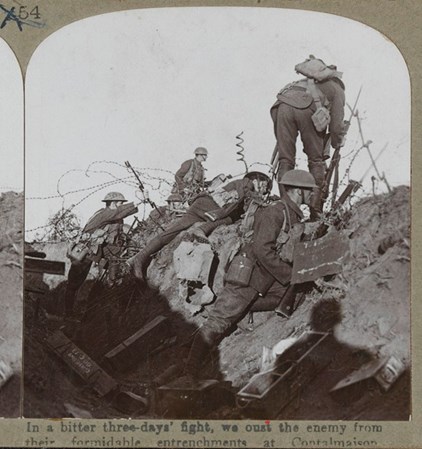

Harold joined his new battalion in France, and over the course of 1916 he would see much action. The 10th DOW would go on to distinguish themselves during the Battle of the Somme on 10 July when they took part in the capture of Contalmaison as a constituent of the 69 Brigade. A report of the day’s events composed by the battalion’s CO refers to the part that the battalion played in neutralising the German threat to the Brigade’s advance; ‘owing to the excellent work done by our snipers and Lewis Gun, the enemy were unable to cause serious losses to our advancing troops, and eventually were compelled to abandon this gun. This gun was later captured by the attacking battalion. The excellent work done by our snipers and Lewis Gun may be judged by the fact that when we advanced, we found 15 dead Germans shot through the head […] the magnificent behaviour of all ranks during the attack when under intense artillery barrage and machine gun fire was beyond all praise.’[8]

Above: Photograph captioned ‘In a bitter three-days fight, we oust the enemy from their formidable entrenchments at Contalmaison’ (Image – collection.nam.ac.uk)

By mid-August the battalion were in Ploegsteert to the south of the Ypres Salient for a spell, before returning to the Somme in September. By the end of the month, they were deployed in the Martinpuich sector at Peake Wood; a copse on the south-east side of the road to Contalmaison. October saw a quickening in the battalion’s activity, the 10th DOW’s war diary proper briefly refers to the events of the first few days of the month:

1 October 1916

The Battalion left Peake Wood for Gourlay Trench in the morning. During the afternoon a heavy bombardment was carried out by our guns in preparation for an attack by the 70th Brigade. Word was received later that they had gained their objectives. Day fine.

2 [to 4] October 1916

Orders received from Brigade that Battalion would proceed to front line on 2nd Inst., the 69 Infantry Brigade relieving the 70 Infantry Brigade and our battalion relieving the 8th KOYLI. Orders were issued to companies as per attached copy marked “A”. the relief was very much delayed owing to congestion in the trenches and was not complete until just before daybreak[9].

Above: A sentry at the junction of Gourlay Trench and Gordon Alley, Martinpuich, 28 August 1916 (Image – warhistoryonline.com)

These entries barely reflect the action that took place over this period. A report by Lieut. H W Lester, Adjutant of the 10th DOW, headed “A”, appended to the war diary, goes into greater detail describing the events of the morning of 4 October 1916:

This morning at dawn two strong bombing parties proceeded up the sap leading from M.22, b.2.9¾ and up sap from point 93; at the same time a platoon went over the top from the left of point 93. The bombing parties were allowed to proceed up these saps, which are not more than about 3 ft. deep, until quite close to O.G.2. when heavy machine gun fire was opened on both parties and hostile bombing attacks were at the same time made from arrow heads at O.G.2. The remnants of both bombing parties were forced to retreat to O.G.1.; the platoon which went over the top only advanced about 10 yards when all except three privates were rendered casualties. From a very careful inspection of O.G.2. with the aid of periscope and glasses it is apparent that it is very strongly held. The trench has been considerably deepened and sentries in ‘niches’ in the parapet may be seen every eight or ten yards. There is still a good deal of uncut wire in front close to the road and I am of opinion that the trench and wire should be dealt with by the artillery; owing to the depth of the trench 18 pounders would be of very little use unless a direct enfilade can be obtained. There is undoubtedly a machine gun at or about M.15., d.7.0. Considerable sniping goes on from the houses in Le Sars two snipers are thought to occupy the chimney which is still standing at about M.15.d.Timed and dated 12 noon 04.10.16 [10].

A further report by Major R H Gill, 10th DOW, details the action later on that day:

In the afternoon I received verbal orders to attack O.G.2. with two companies’ 10th W. Rid. Regt. From M.21.b.5.8. to M.15.d.25.30. I at once proceeded to O.G.1. and issued Operation Order No.1. At 6.3pm both companies went over the top and crept up under our barrage until it lifted at 6.8pm. They then advanced under intense rifle fire and traversing fire from at least three machine guns. The ground was so heavy that it took them ten minutes to cover 50 yards. Some got to the German wire (which was practically intact) others as far as the enemy’s parapet which was fully manned and where the enemy had no difficulty in dealing with them in their exhausted condition. 2nd Lieut. H. Kelly, CSM O’ Shea and two men alone succeeded in entering the German trench remaining there bombing and fighting down it until enemy reinforcements arrived overland, killed one man and wounded the CSM. 2nd Lieut. Kelly then retired carrying the CSM back to our own lines. Here with the assistance of part of “C” Coy he repelled a German counterattack. These two companies behaved with the utmost gallantry but their task being an impossible one they failed to take the trench and were decimated[11].

It was this day, the 4th, that Harold’s war came to an end. At some point during the day, possibly whilst going over the top, he was shot in the right eye. He again entered the medical chain of evacuation, eventually to be admitted to hospital in Boulogne, where his eye was removed. Arriving back in England on 15 October1916, he was admitted to Tooting Military Hospital on 16 October 1916. He spent 66 days in hospital and his wound was categorised GSW II3; the first element of the category, ‘GSW’, clearly refers to a gunshot wound, the second, ‘II’ subcategorised as Gunshot wounds of the face and the third element ‘3’ as a fracture and lesion – in this case, of the eye. His fitness to serve in the army was reclassified as Bii; Able to walk 5 miles (as opposed to march) see and hear for ordinary purposes (his left eye was unaffected).

Above: Tooting Military Hospital (Image – Uxbridge remembers WW1)

Harold’s wound would continue to trouble him, on 8 March 1917 he was admitted to the War Hospital Bradford with inflammation of socket of eye. After treatment, he was discharged from their care on 14 March 1917.

The army decided he would not continue to serve in a military role, the adjutant for the DOW West Riding Regiment’s depot at Halifax wrote to the OIC Infantry Records at York as follows:

The attached documents of No. 10915 Pte. H. Wood are forwarded for favour of obtaining the authority of the G.O.C.-in-C. N. C. for the transfer of this man to Army Reserve Class P. Med Cat’y B.ii, Trade: Wool Combing. This man is to be employed in the Textile trade with the firm of F. Illingworth & Co Bradford. Home address 20 Surrey Street, West Bowling, Bradford. I have not issued A.F’s W.3455 & 3456 please. From Capt. & Adj. for O.C. Depot West Riding Regt, Halifax, 17/03/1917[12].

Harold was transferred to Class P army reserve on 2 May 1917. Class Prefers to men who were otherwise fit to serve in the military (albeit not in a front line role, rather in an auxiliary or administration capacity) in a medical category no lower than Ciii (or C3) but whose contribution to the war effort would be “deemed to be temporarily of greater value to the country in civil life than in the army but who, as a result of having served in the army or Territorial Force, have contracted disabilities which would, if they were discharged, have rendered them eligible for consideration for a disability pension, or who are qualified by length of service to receive a pension.”

Harold’s return to civilian life would eventually see him settle down. At the age of 24, he met and married Lily Tordoff, aged 20, a spinster, of Coal Street, Caddy Field, Halifax, on 27 May 1918, at St John the Baptist Parish Church, Halifax. On the marriage certificate his occupation is shown as labourer and his home address as Ellerburne Street, Thornaby on Tees, North Yorkshire. After the trauma of the war, Harold was looking forward to a more peaceful life and domesticity beckoned. On 9 November 1918, Lily presented Harold with a baby daughter, Sarah Jane Wood.

Above: St John the Baptist Church, Halifax, where Harold and Lily married (Image – familysearch.org)

But tragedy was just around the corner, on the 17 November 1918, Harold died from influenza just 8 days after his daughter’s birth, and 6 days after the Armistice. The death certificate states that he died at 2 Coal Street, Halifax, in the presence of his mother-in-law Mrs Elizabeth Kendall, who was also the informant. The army were unaware of Harold’s death, and on 15 September 1921 sent a postcard to the last known address held for him of 20 Surrey Street, requesting his current address for dispatch of the 1914-15 Star. It found its way to Harold’s sister Florence at 7 Surrey Street, who responded. The army wrote back to her on 19 September 1921 for further information:

Madam, On 15/09/21, a postcard was dispatched to Mr H Wood, 20 Surrey Street, West Bowling, Bradford, requesting him to forward his correct address to enable me to dispose of the 1914/15 Star, awarded to him in respect of his services as No.10915, West Riding Regiment. It is observed that the above-mentioned p.c.(postcard) has been returned signed by you. I have therefore to request that you will be good enough to inform me under what circumstances you signed same, and what relation you are to the above-mentioned soldier. If Mr H Wood is now deceased, will you please inform me date of death, as this information will be required for record purposes. A stamped addressed envelope is enclosed for your reply[13].

Florence replied as follows:

Dear Sir

In answer to your letter date 19/09/21. Mr H Wood is my brother and he died with the flu 3 years ago on the 25/11/1918 (sic)

Yours, Mrs G Pickup [14].

By the time of the 1921 census, Harold’s widow Lily was living at 20 Mount Street, Halifax, with their daughter Sarah Jane aged 2 years 7 months, and her stepfather Charles Kendall aged 59, listed as the Head of the House, and her mother Elizabeth, aged 46. Lily was employed by John Holdsworth & Co Ltd, Worsted Spinners & Manufacturers, Shaw Lodge Mills, Halifax, as a Twister of Worsted. Lily went on to remarry on 8 October 1921, to Joseph McGuinness, again at the Parish Church, Halifax.

Image: Aerial photo of Shaw Lodge Mills, Halifax, where Harold’s widow Lily worked as a Twister of Worsted in 1921 (Image – story.theholdsworths.org.uk)

The army, with the assistance of the Ministry of Pensions at Victoria Tower Gardens, SW1, finally tracked Lily down. They corresponded with her at the address supplied by the Ministry, received a response in her new married name of McGuinness, and wrote further on 13 December1921 as follows; ‘Madam, A verification of address card forward to Mrs L Wood at 5 Coal Street, Caddy Fields, Halifax, has been received in this office, it is noted has been completed by you. To enable me to correctly dispose of the medals awarded to the above mentioned would you kindly inform me under what circumstances you completed the card. If you and Mrs Lily Wood are one and the same […] please state. An immediate reply is required please, an addressed envelope being enclosed for the purpose [15].

She replied in a letter to the Infantry Record Office at York, date-stamped 21 December 1921, where Lily explained her new marital circumstances: ‘…Mrs H Wood and Mrs Joe McGuinness is one and the same as I was married the eighth of October 1921. If you wish for proof I was married at the Parish Church, Halifax’, signed Mrs McGuinness [16]. The 1914-15 Star was sent to her at 7 Prescott Place, Halifax; her stated address, and she sent a receipt on 15 May 1922.

For Harold to have survived the war, suffered two wounds, one of them life-changing, only to die in the Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918-20, having just married and started a family, was a cruel twist of fate; a family’s tragedy that serves as a microcosm of the greater universal tragedy of the War to end all Wars. It was reflected across the land, many serving and former soldiers died in similar circumstances during the pandemic. The posthumous campaign medals awarded to these families were, to some at least, a consolation, the state’s recognition that their loved one’s life meant something. Harold’s 1914-15 Star, along with the British War Medal and the Victory Medal, must have been received in this spirit by Lily, she clearly treasured these awards enough to apply for them, and in time, they could be passed on to Sarah Jane as a tangible memento of the father she never knew.

Article by Paul Blumsom

References:

- Carver, Field Marshal Lord, The National Army Museum Book of The Turkish Front 1914-1918: The Campaigns at Gallipoli, in Mesopotamia and in Palestine, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 2003, p.59.

- Moorehead, Alan, Gallipoli, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1956, p.256.

- Ibid, p.257.

- Report by Captain Vivian Norval Kidd dated 17/08/1915 appended to WO/95/4299 War Diary 8th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment30/06/1915 to 31/12/1915Ancestry.co.uk.

- Moorehead, pp.291-2.

- WO/95/4299 War Diary 8th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment30/06/1915 to 31/12/1915Ancestry.co.uk.

- Garth, John, Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-Earth, Harper Collins, London, 2003, pp.103-4.

- Appendix ‘B’ to WO/95/2184/1 War Diary 10th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment 01/08/1915 to 31/10/1917 The National Archives.

- WO/95/2184/1 War Diary 10th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment 01/08/1915 to 31/10/1917 The National Archives.

- Report by Lieut. H W Lester, Adjutant of the 10th DOW, headed “A”, appended to WO/95/2184/1 War Diary 10th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment 01/08/1915 to 31/10/1917 The National Archives.

- Report by Major R H Gill, 10th DOW, appended to WO/95/2184/1 War Diary 10th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment 01/08/1915 to 31/10/1917 The National Archives.

- WO363, Service Record of Private 10915 Harold Wood, The National Archives.

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

Other sources:

Miles, Captain Wilfrid, Official History of the War Military Operations France and Belgium 1916, Vol.II, Reprint by Battery Press, Nashville, Tennessee, originally published 1938, p.432.

Medal Card of 10915 Harold Wood, ref: WO372/22/43302, The National Archives

WO364 Pension Record of Private 10915 Harold Wood