G Battalion 1st Tank Brigade at St. Julien on 19 August 1917 by Peter Arscott

- Home

- World War I Articles

- G Battalion 1st Tank Brigade at St. Julien on 19 August 1917 by Peter Arscott

Peter Arscott relates the exploits of G Battalion 1st Tank Brigade at St. Julien on 19 August 1917.

[This article first appeared in Stand To! No.37. Members received three issues of Stand To! - the Journal of The Western Front Association, and Bulletin, or in-house member-magazine a year and access to the full Stand To! Archive online].

The development in 1915 of 'Landships', as the original tanks were called, was not welcomed by the War Office and it was left to the Navy, led by Winston Churchill, to be the 'midwife' of this conception. Although eventually they became part of the Army's Order of Battle, there was great reluctance to accept them. The earlier failure of the tanks, through no fault of their own, did little to change that opinion, and disbandment of the Tank Corps was expected in the summer of 1917. However, their astonishing success at the Battle of Cambrai in November of that year, was sufficient to ensure its future. But that battle in which 400 machines were used might never have occurred were it not for the small but important success of about half a dozen tanks a few weeks earlier, against strong German fortifications. This is the story of that almost unknown but significant fight.

1st Tank Brigade - La Lovie

Two miles to the north of Poperinghe lies La Lovie Chateau, a magnificent XVIII century mansion, set in a park, its lake and lawns giving an air of tranquillity befitting its present use as a refuge providing home and employment for the mentally handicapped. Yet everything about 'La Lovie' seemingly belies its past some seventy odd years ago when, in 1917, it was the headquarters of General Gough's Fifth Army. Then it would have been alive with feverish activity and a continuous stream of staff cars, motorcyclists, saluting sentries and all that one would expect of a busy wartime headquarters near the battle front.

Behind the chateau lay the headquarters of General Ivor Maxse's XVIII Corps and about 500 yards to the north there was, in a tented encampment, the headquarters of the 1st Tank Brigade commanded by a comparatively young Colonel, who rejoiced in the name of Christopher d'Arcy Bloomfield Saltern Baker-Carr. He had been an instructor at the Small Arms School at Hythe before the war but had taken early retirement only to rejoin the Colours at the outbreak of war. Since the announcement of such a name was sufficient to open most doors, it was not long before he was wearing a makeshift uniform and acting as chauffeur with well known motoring celebrities 'doing their bit' transporting high-ranking and influential officers around France.

His knowledge of small arms made him a suitable choice to head an embryonic machine gunners school which later became the Machine Gun Corps. Since the first tanks were originally part of this Corps it was a natural step for such a personage to participate in the development and use of this new machine which eventually led to his command of the 1st Brigade Tank Corps comprising D and G Battalions.

The Corps Commander in the field was his friend Brigadier General Hugh Elles who, with Baker-Carr and other pioneers of mechanical warfare, made an effective team in their fight against—not the Germans—- but the War Office staff and politicians who wished to see the tank idea scrapped. So many of them were wedded to romantic memories of cavalry charges in previous wars and had a profound dislike of machinery of which they had little understanding and could easily lose control. Col Baker-Carr's original and independent frame of mind gave him a contempt for the 'military mind' and its mental rigidity. He had no fear of proclaiming his views to more senior officers which did not endear him to conventional staff officers at GHQ. General Maxse, with whose corps Baker-Carr served at La Lovie, was, however, an exception who had some understanding of the potential of this new weapon despite its previous misfortunes in the field.

Baker-Carr had seen the disastrous events that befell the tanks from their first day in battle on the Somme in September 1916 to their sojourn in the Salient nearly a year later. They had gone into action prematurely, their crews having had little more than three months training. Instead of the 150 machines originally proposed only forty-nine were available and thirty-two reached their starting points of which a mere eighteen were able to take effective action. Most of the Tank Corps people thought their secret had been given away for little gain and had wished to wait until the number of machines was overwhelming. In any event the nation was denied the great victory on 15 September that would have cleansed the memory of the carnage of 1 July.

Baker-Carr remembered Messines, Arras and Bullecourt where the tanks made little difference to the outcome of those battles and he had personally seen them off into the Salient on 31 July 1917 where so few were to emerge despite the use of a new unditching beam. The wet glutinous mud that sucked in flesh and bone was just as eager to consume these 30-ton steel boxes. After these battles the verdict of General Gough's Staff on the performance of tanks in action was quite succinct—they decreed: 'Tanks are unable to negotiate bad ground. The ground on the battlefield will always be bad. Therefore tanks are no good on the battlefield.'

They came to this conclusion after it had previously been agreed that tanks would not be used where weather or ground conditions were bad. On 23 July 1917 the Director of Mechanical Warfare, Col Stern, wrote to the Prime Minister complaining that because of their misuse and consequent failure . . . it now seemed likely that the Army would cancel all orders for mechanical warfare'.

Three months later Winston Churchill, the Minister of Munitions, told Col Stern that the War Office thought 'there had been a total failure of design and the money spent on tanks wasted . . . their belief in mechanical warfare was so low that they proposed to give it up entirely'.

It was little wonder that the Tank Corps saw that its days were numbered. There were many in London and GHQ who, from the beginning, regarded the tank as a very 'ugly duckling' which should never have been born and more than ever now, wished to be rid of it.

Inside a tank

An infantryman, knee deep in mud and being shelled night and day, may be forgiven the sin of envy at the lot of the tankmen who went into battle for a few hours only and were protected by bullet-proof armour. Had he the opportunity to change places he might though, have regretted it. On climbing into a tank he would be surprised by the small size of the compartment into which was crammed the crew of eight, an enormous 105 hp tractor engine with a large gearbox together with, in the case of a 'male' tank, two Hotchkiss six pounder QF guns, four Lewis guns, several thousand rounds of ammunition and everything from measuring tapes to tarpaulins. Once the engine was cranked into starting by three or four men, the noise was ear-splitting. Speech was impossible; all communication being affected by the hitting of a spanner on the casing to attract attention, followed by hand signals. Only the noise of the six-pounder gun firing could penetrate that deafening roar.

When an armour piercing bullet hit the casing, red hot flakes of steel flew off the inside causing injury to the crew; lead bullets melted on impact spraying hot lead through any aperture or joint in the plating. Masks of steel mesh were provided to prevent injury but they were inconvenient and could not be used during the frequent gas attacks. In battle vision flaps had to be tightly closed against concentration of fire, direction being maintained by peering through minute holes about 2-3mm. in diameter drilled in the plating.

The heat from the engine was so intense - often reaching as much as 125°F—that a driver could burn his hands on the hot steering wheel and, in the case of the Mark V tank, it even caused ammunition to explode. There was no suspension and the gunners sat on bicycle saddles. There was little to hold on to except a red hot exhaust pipe when the machine lurched into a shellhole and out again.

Ventilation was, at the best of times, very poor, being little more than a radiator fan sucking in air but even this failed to remove carbon monoxide fumes and, in the case of tanks armed with Lewis guns, it drew in acrid, choking, cordite fumes, mixing with the nauseous smell of oil and petrol, across the faces of the gunners. The machine would be in almost total darkness, the only light available to map read being from three or four festoon lamps.

Towards the end of the war a troop carrying tank was designed but proved to be a failure because the infantry, incarcerated inside, were rendered non-combatant by acute nausea after only a short journey.

Our infantryman would almost certainly prefer his own lot had he seen a tank hit in the petrol tanks, which, in the Mk I, were located inside the cab, within a few inches of the heads of the commander and the driver. There could be no escape in the ensuing instantaneous inferno.

The Battle of Langemarck and the Pillboxes

After the inconclusive results at the beginning of the Third Battle of Ypres another attempt to advance out of the Salient was made on 16 August 1917 by the 11th and 48th Divisions of XVIII Corps. Langemark was taken early in the day but little progress was made farther south owing to the presence of a network of German concrete blockhouses, or pillboxes as they were generally known, and gun pits. This area came within the domain of G Battalion, of the 1st Tank Brigade and was where they had been 'blooded' on 31 July. No. 20 Company, which had been in Corps Reserve at their advanced park near Fantasia Farm on that day, was now ordered into action in support of the two divisions. The brigade's machines were normally kept at Oosthoek Wood about two and a half miles to the north east of Poperinghe where they were served by a railway line and military road. During the battle, however, forward parks situated about halfway to the canal and close to the Brielen Road were used, to avoid long journeys to the Front. The ground conditions had not improved and, since the machines were not allowed to use the hard roads, eight of them became irretrievably ditched. The remaining four were so late arriving that they did not see any action, much to the dismay, if not the expectation, of Colonel Baker-Carr.

The blockhouses and gun pits which had curtailed the advance lay mainly alongside the St Julien-Poelcapelle Road in the vicinity of Keerselare, where the Canadian monument now stands. The largest however, called the Cockcroft, was about 500 yards up the Langemarck Road, had walls about eight feet thick and housed up to 100 men. The others were slightly smaller but, like the Cockcroft, had been built in the ruins of farmhouses protected by outlying machine gun nests and were considered to be impregnable. The Cockcroft, Maison du Hibou, Triangle Farm, and Hillock Farm were indeed a formidable part of the German second line. General Maxse's staff had already estimated that casualties of about 1000 men would have to be expected if a direct infantry attack was made against them. Even then, they could not be certain of success.

Baker-Carr saw this as an opportunity to prove what his Tank Brigade could do. It was a situation the Corps had long been waiting for, so he offered to capture the strongholds with his tanks incurring less than half the expected casualties, provided he could plan the attack. It must have been a supreme act of faith, since he could not have foreseen the events which were to follow. General Maxse had nothing to lose and since he had confidence in Baker-Carr from his Machine Gun Corps days he readily agreed, accepting with equanimity all the preconditions demanded. Having some faith in the potential of tank warfare, Maxse was prepared to give him the opportunity to adopt, for the first time, some of the tactical principles laid down more than a year earlier by Col Swinton. Small as it was, this would be the first battle spearheaded by tanks with the infantry following up in support.

It was decided to form a company of twelve machines out of G Battalion; at dawn they would attack the fortress farms which would be obscured from the German third line by a dense smoke screen. They would have to use the existing paved roads to avoid ditching, although being narrow they could only take machines in single file.

Like Nelson at the Battle of Copenhagen they were to 'sail' past the enemy forts firing broadsides in true nautical fashion—perhaps in recognition of their naval origin! They had not been called 'landships' for nothing.

17 August Preparations

Col Baker-Carr was keenly aware that surprise was essential to avoid immediate German artillery saturation of the Poelcappelle Road so he insisted that there should be no warning bombardment before the attack as was customary. An RE8 from No 7 Squadron RFC stationed at E. Proven would patrol the line during the tanks' approach march to mask their sound, assisted by some light artillery and machine gun fire. In view of the protection to the blockhouses given by the machine gun nests, it was decided that the Infantry should follow in file not less than 250 yards behind the tanks and occupy the forts only after they had been captured and been given the signal to 'come on' by the tanks—thereby minimising casualties. That was the general plan but there was a lot of staff work to be completed in the next twenty-four hours involving the commanders of the 1st Tank Brigade, G Battalion, 11th and 48th Infantry Divisions, artillery batteries and No 7 RFC Squadron. Nevertheless, it was lunchtime at La Lovie on 17 August when twelve selected subalterns and their crews were warned to stand by and prepare to move off that night for the front line.

It was soon found that twelve good machines were not available. One of the crews had been unable to retrieve its tank as it lay still on the other side of the canal with a broken shaft. So they were down to eleven, two of which would have to remain in reserve at their last overnight stopping place before going into action. Meanwhile there was much to be done. Lorries would leave the tented encampment at La Lovie at 1.30pm for the battalion forward parks at Halfway House and Ghent Cottages where the machines had been brought out of the Salient. Portable equipment, maps, compasses, clocks and other paraphernalia were hastily gathered together as the crews departed. The remainder of the afternoon was spent filling the tanks with petrol, oiling and greasing, checking guns and ammunition, and getting everything ready for the forthcoming journey and battle.

At 6pm all machines and crews were ready and moved off. Their rendezvous for YZ night was to be at Bellevue Farm not far from Wieltje behind the old British front line. However, they dared not cross the Yser Canal until after dark, so the first stopping point was at Murat Farm close to Essex Farm Casualty Clearing Station where John McCrae wrote his poem 'In Flanders Fields'. Most troops avoided the place if possible because of the dreadful smell of human remains that permeated the air. Nevertheless, they lay-to for a while, topped up fuel tanks from the petrol dump nearby and waited for nightfall to make the crossing over the canal at Marengo Causeway, about 500 yards to the north. This was a sandbagged earth crossing point specifically built for heavy traffic. It was, of course, shelled but with such regularity that by careful timing the worst of the barrage could be avoided. Gas was another matter though. The acrid fumes lingered, particularly over the water, and three weeks earlier Col Hankey, CO of G Battalion and several of the crews had suffered minor injury through inhalation when they came this way. Now there was little and so it was that with just enough light to see by, all eleven machines crossed over without incident.

The whole operation had thus far gone very smoothly as they turned south to join Boundary Road near La Brique which would take them to Bellevue. The night had suddenly become very dark and as the column turned into the road it met, head on, a tank returning to the canal having just been retrieved from the line, followed by dozens of mules, limbers and supply columns sometimes filling the whole width of the road. Eleven clattering tanks approaching caused even more havoc and the drivers could do no more than wait for the handlers to disentangle the animals from their own and others harnesses and the chaos to subside until the road became clear. From Boundary Road where the tanks joined it to the farm where they would lay-up for the next day, is about one and a half miles. Their journey took five and a half hours. It was 2 o'clock in the morning of 18 August when they finally turned off the road to a field called, inappropriately, 'Bellevue'.

18 August The Plan

Bellevue Farm differed little from any other part of the front. All vestiges of the farm that once stood there had long since gone although there remained a piece of hedge to afford cover for the tanks! The field was surrounded by 18-pounders which fired most of the night so sleep for the weary crews was out of the question. They would not depart this site until the early hours of the 19th, nearly twenty-four hours away and, meanwhile, there was a divisional conference during the day for the officers to attend for a final briefing. Battalion Orders had been quite explicit but now it was very necessary to meet the infantry commanders who would support the tanks. One of the objectives was in the 11th Division's area, the remainder being in the 48th's and close liaison with both units was vital for the success of the operation.

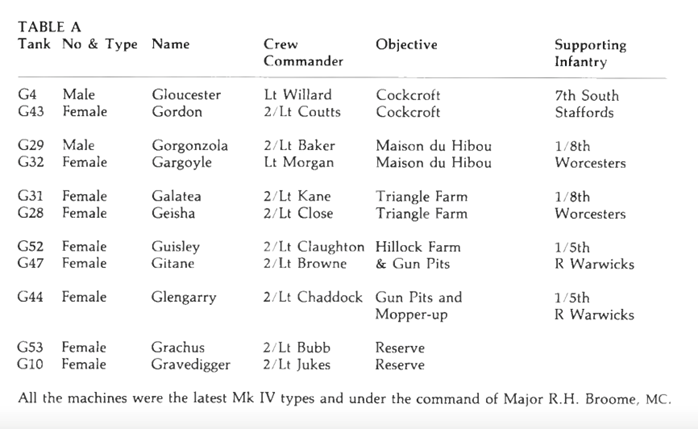

The original orders had required twelve tanks to be employed, four of which would remain in battalion reserve at Bellevue. Subsequently this was changed to nine in action and two in reserve, the 12th still being completely immobile by the canal. For the line-up in order of procedure see Table A.

|

|

Table A |

Battalion Headquarters for the occasion was at '14 Gordon Terrace' the Divisional Headquarters being close by. Hardly desirable Victorian artisan residences, these 'dwellings' were in fact no more than corrugated iron dugouts in the west side of the canal bank, infested with flies from the rotting corpses which floated on the canal. Here the officers could rest and wash prior to the midday conference. Those who were to be supported by the 48th Division (144 Brigade for Maison du Hibou and Triangle Farm; and 143 Brigade for Hillock Farm and Gun Pits) became acquainted with their infantry opposite numbers and details of the operation agreed. However, the two officers, Coutts and Willard, who were to be with the 11th Division (33rd Brigade) were less than happy with their infantry and had considerable misgivings that support would be forthcoming as planned. In the event their fears were not unjustified.

It was evening when the commanders returned to their crews at Bellevue. During the day the tanks had once again been prepared for the coming battle—guns rechecked, and spuds—large steel plates clamped onto the tracks to improve grip— bolted on, and engines checked over. The padre had even conducted a service during the day for the men. There was little to do but rest and wait for lam next morning when the nine machines would line up in the road to commence their approach march to the Steenbeek crossing at St Julien. G4 was to lead the column with G44 bringing up the rear and G53 and G10 remaining behind in reserve.

19 August The Magnificent Seven

The column had about three-and-a-quarter hours to travel to St Julien about one-anda-half miles away before zero hour at 4.45am. This part of the journey would have to be accomplished very slowly in bottom gear to reduce the noise of the machines as most of it would be on the eastern slope of a ridge and the sound travelling directly to the German lines might warn the enemy. Although the ridge constituted little more than a slight gradient, the slope could be identified by the debris remaining on the eastern side, uncleared because of the persistent shelling. Whereas on the western slope, obscured from the guns, the road was kept free.

They had not been long on their way before there was a hold up. G4, the leading tank commanded by Lt Willard, was having trouble with the exhaust system which was slowly asphyxiating the crew. The leak was temporarily repaired but within the hour it recurred and, since they were now on the eastern slope, they could not stop the column to carry out further adjustments. Willard had no choice but to proceed to the Steenbeek with all doors and hatches open. As he could not go into battle in his present condition he pulled over to allow 2/Lt Coutts in G43 to take the lead.

The actual crossing of the Steenbeek had been made possible by the 184th Tunnelling Company attached to G Battalion. Originally the stream had been about ten feet wide with five feet high banks but continuous shelling had totally destroyed its formation so that it was now a forty feet wide swamp. The tunnelling company had dropped fascines into the bed which compressed into a submerged causeway.

Unfortunately 2/Lt Kane in G31 misjudged his position and ended up irretrievably ditched in the bed of the stream and could take no further part in the action—fortunately there was still room for the others to pass. Meanwhile, Coutts in G43 arriving at the starting point in St Julien well before zero hour, waited for the others to catch up. The column was now down to effectively seven machines and for Major Broome monitoring events at the temporary Company HQ at Cheddar Villa, this must have been a time of deepest despair. He was well aware of the political and tactical importance of this attack but through misfortune his force had lost a fifth of its strength and the loss of Willard's male tank was crucial since its shell armament was essential for use against the Cockcroft. Coutts, on his own with light machine guns, could do nothing and he was not even sure of his infantry support. Major Broome had only one other male machine with six pounders, which was Baker's, already committed to Maison du Hibou and there was now no time to bring up the reserve machines. The whole operation was beginning to disintegrate but they had no choice but to go on.

At zero hour—4.45am—the smoke shells and the shrapnel barrage came down and the remainder of the column set off up the Poelcappelle Road, each machine attacking its selected target in succession as approached.

The Gunpits were engaged in turn by Browne (G47) together with Claughton (G52) and Chaddock (G44). When to their astonishment the enemy fled, they moved on to Hillock Farm about fifty yards farther along the road. After a short engagement its occupants fled too. Even Willard, in his defective machine, managed the short journey from St Julien and made an attack on Hillock Farm but had to return because of the engine trouble. He was, in fact, wounded by shellfire when he got out of the tank because of the fumes. An infantryman of the Worcestershire Regiment gave him assistance in restarting his engine which enabled him to return.1

The smoke screen and light artillery barrage coupled with the total surprise demoralised the Germans. It also reduced the tanks' visibility to a few hundred yards. Whilst this battle was continuing, Close in G28 was committed to taking on The Triangle alone, since his companion machine G31 had not been able to move out of the bed of the Steenbeek.

Accounts of Close's activities against his objective vary considerably. They report that he had ditched nearby; that his guns were out of action; that he and his crew were trapped inside; that he was captured and managed to escape. Other sources state that the German occupants of the fort reputedly 'put up a good fight' and 'were made of stronger stuff' being 'taken at the point of a bayonet'.

However, it seems unlikely that the crew of G28 could have been trapped in their machine outside Triangle Farm since the British line had been advanced beyond it by the capture of Hillock Farm and Maison du Hibou, and Morgan in G32 at least, would have passed by him as will be seen.

Close's Operational Report, like all of them, is brief and surprisingly does not even mention Triangle Farm where such dramatic events are believed to have occurred, but it does tell of the misfortunes that befell him some 500 yards north of it. One can only speculate what really happened. It may be significant that Col Baker-Carr, in his preliminary Operational Report, prepared fairly early in the day and possibly based on reports by pigeon carrier, states: 'Triangle Farm was not occupied by the enemy'. This is supported by Lt Baker's Battle History Sheet of G29 in the manuscript on which he has inserted 'Triangle Farm was of no importance'. However, Baker-Carr's autobiography written some two years later remarks on the resistance put up by the Germans here and the War Diary of l/8th Worcesters notes that after the surrender of Maison du Hibou B Coy carried Triangle Farm.

It is likely, therefore, that Lt Close on approaching the strongpoint and finding it in ruins (as later reported by the infantry) concluded that it had already been evacuated and sent off a pigeon with a message to that effect signalling the infantry to 'come on'. He then drove farther up Poelcappelle Road, as did Morgan in G32, presumably to look for other targets. He was probably unaware that Triangle Farm was, in fact, occupied, the enemy awaiting the approach of the Worcesters when they would rise to their loopholes fiercely defending the stronghold until overcome at the point of a bayonet. Five hundred yards north of Triangle Farm Close was attacked by machine gun fire from strongpoints at Vieilles Maisons where he was wounded in the hand preventing him from using the brakes, causing the tank to ditch in the mud. The machine gun fire knocked out five of his Lewis guns—they were always very vulnerable—and the remaining one was kept inside for emergencies.

Close and his crew were trapped here for sixteen hours before they were able to get out of the tank after dark by removing a sponson and then disabling the machine by blowing up the clutch with a grenade. The battalion war diary records that he returned to camp on the evening of 20 August in an exhausted condition—some thirty-six hours after zero hour. It is possible that he had been captured for a while as suggested by Browne particularly as he and two crewmen had been wounded.2

Baker and Morgan fared much better. Baker in G29 missed his turn off to Maison du Hibou because the road was obliterated by mud. Instead he drove up the Poelcappelle Road and succeeded in getting behind the fortifications. His left hand 6-pounders were pointing directly at the rear doors of the largest building and, after some forty rounds had entered the fort and Morgan in G32 had arrived behind to add his weight to the melee, about sixty Germans fled, half of them being captured by the 1/8 Worcesters who took occupation. By about 6.30am it was all over.

In attempting to swing round to return home, a sudden burst of machine gun fire on Baker's front visors caused the tank to lurch against a tree and slide into a large shell hole by the side of the road where it stuck fast.3 Heavy fire prevented evacuation so he used his right-hand gun against the German line to the east, until the sinking of the machine prevented further elevation of the gun. The barrage continued to fall close by so he got out with his crew and offering support to the infantry, gave them his three remaining Lewis guns and ammunition. Not being needed, he returned on foot with his crew to the rallying point, but on the way back a German shell fell on his party, killing one and wounding another.

With the stronghold secured, Morgan proceeded farther up the Poelcappelle Road and engaged some machine gun nests at Vieilles Maisons before turning round and heading for home, no doubt unaware of Close's predicament nearby.

Meanwhile, Coutts in G43 was plodding alone up the Langemark Road to the Cockcroft. At about 6am he was heavily engaged from three sides by the fortress and its outlying machine gun nests. There was a fierce gun battle for about three-quarters of an hour but early on one of the Lewis guns jammed. The gunner had to pull it out to clear the blockage or replace the gun and immediately received the full concentration of fire from the enemy machine gunners who were aware of the tank's sudden vulnerability. A hail of bullets hit the empty gun mounting and shattering into splinters hit the gunner full in the face, badly wounding and blinding him. One of the gearsmen immediately took his place with a fresh gun. The other put a field dressing on the wounded man and propped him up out of the way.4 During the course of the engagement Coutts, like Baker, slipped off the road and became firmly ditched just south of the fortress.

The Germans, however, were unaware that the machine had stopped involuntarily and that it had, indeed, only machine guns. At a distance and in smoke, the cooling jacket around the Lewis gun did not look unlike the muzzle of the Mk IV's sixpounder. They were still being attacked by the stationary tank and, fearing the hail of shell shot, about fifty of them fled from the buildings. Coutts then decided it would be safer to get out of the tank and, carrying his wounded gunner to a shell hole and leaving a revolver in his hand, he set about forming Lewis gun positions with the remainder of his crew. His support, the 7th South Staffords, had not responded to his signal to 'come on' performed by waving a shovel through the roof hatch and two men were sent back to them. On their return, they reported that the infantry would not move so Coutts himself went back, spoke to the CO and returned with about thirty infantrymen to consolidate his Lewis gun line. He then camouflaged his tank and left three men inside with rifle grenades to hold it as a strongpoint. It was nearly twelve hours later before they were able to arrange for their wounded comrade to be taken to a field dressing station and returned to camp.

The South Staffords war diary records observation of '3 tanks moving up to Poelcapelle'—[Baker, Morgan and Close] 'and only 1 machine (not 2) towards the Cockcroft'—[Coutts]. They then put up a smoke barrage on Maison du Hibou but were dismayed to see Coutts ditch one hundred yards (sic) short of the Cockcroft. The diary's author explains that since the battalion had orders not to attack without tanks they decided to wait for the Worcesters on their right to commence their attack on Maison du Hibou. The Staffords 'then decided to attack the Cockcroft without the cooperation of tanks'. However, there is an unexplained discrepancy here, since the diary times the commencement of their attack as about 9.30am and it being over by 10am, whereas the XVIII Corps Report of Operations records all objectives having been taken by about 6.30am. It would seem that Coutts' personal exhortation was probably coincidental with the infantry attack It is surprising that the defenders of the Cockcroft gave in when confronted by the solitary tank. There is rarely time for contemplation in battle but had they done so they might have realised that it was armed only with Lewis guns—little better than an automatic rifle—and was stuck in the mud so it could do them little harm behind their concrete walls. It is perhaps understandable that the occupants of Maison du Hibou should flee when confronted by two tanks, one of which was pumping six-pounder shells in their back door and the other covering gun apertures with automatic fire. Undoubtedly they heard the sound of Baker's and Morgan's battle nearby, particularly the former's sixpounders, but the smoke screen probably hid the reality from their view. Perhaps some of the fleeing Germans from Maison du Hibou who managed to escape shouted terrified warnings to the Cockcroft defenders as they fled to the German third line.

By the end of the day four machines returned to the canal bank under their own power—G32 (Morgan), G44 (Chaddock), G47 (Brown) and G52 (Claughton). G4's engine (Willard) finally failed in the bed of the Steenbeek where the machine remained to take the place of G31 (Kane) which, no doubt, was eventually hauled out. Baker's G29 became a post-war landmark on the road to Poelcappelle. Of the ultimate fate of G29 (Close) nothing is known but no doubt it ended up as scrap. Coutts' G43 appears to have been salvaged shortly after the battle but he was never to command it again—• receiving 'Gordon II' a month later.

During the course of the battle Col BakerCarr was awaiting news of the action at General Maxse's HQ near La Lovie. At about 7am the first pigeon arrived announcing the capture of the Gunpits, followed shortly after with good news about Hillock Farm. Then, Maison du Hibou — many prisoners captured—and Triangle Farm, where the enemy had put up such a good fight; but there was no news of Close and his crew yet. There was a lull until eventually Coutts' pigeon telling of his astonishing success, came home to roost. As Lt Browne put it 'Coutts was the star turn of the day.'

General Maxse, friend of the Tank Corps, was as delighted as Baker-Carr on hearing the news—but what of the casualties? Had his promise been fulfilled? The figures came swiftly. Not a thousand or even the 500, but just fifteen infantrymen and fourteen tankmen killed or wounded.

Immediately Maxse sent a telegram to GHQ stating that his XVIII Corps had advanced on a front of 1000 yards to a depth of 500 yards—a lot in those days—including the capture of five strongpoints. Total casualties twenty-nine! Quickly GHQ replied asking how it was done. Maxse answered simply 'tanks'.

The news was not long in reaching Tank HQ at Bermicourt a few miles to the west of Arras. It was here that the famous Daily Mail war correspondent W. Beach Thomas was ensconced and he immediately set off to La Lovie for his story. He arrived on the day after the battle but unfortunately all those who took part were enjoying a long, well earned sleep. Rather than let him return empty-handed without a story, several of 19 Company, who had not participated, gave him the information for his article but suitably embellished and exaggerated, almost beyond recognition. The account was printed in the Daily Mail on Tuesday 21 August 1917—much to the delight of the battalion. But Beach Thomas was not the only one impressed. General Gough himself felt it necessary to make an inspection of the crews involved in Oosthoek Wood. To each commander he addressed a few congratulatory words and enquired about infantry support; but on reaching Coutts, his staff ushered him past and he was not given an opportunity to hear of the difficulties encountered with the 33rd Brigade. Nevertheless, Coutts together with Baker and Morgan were given immediate awards of the MC.

|

Views of the battlefield after the third Battle of Ypres, 1917. A soldier looks across devastated country near Ypres showing a derelict Mark IV Tank, shell-splintered trees and general battle detritus, 15 February 1918.© IWM Q 10711 Author’s note: Probably 'Gloucester' (incorrectly thought to be 'Galatea') ditched by the Steenbeek. Taken in 1918. (Tank Museum)

|

The effect of this little action aroused considerable interest in the Army since it was the first time that tanks had been totally successful in action themselves and had, at the same time, saved hundreds of lives, an asset recorded with delight by Haig. It silenced many critics and, whilst the gunfight at St Julien may not have been of great strategic significance, it undoubtedly delayed the day of the Corps' impending disbandment and was a 'straw in the wind' of a hurricane that would blow three months later at the famous Battle of Cambrai.

The attack was, of course, essentially 'one off' and, given the ground conditions, succeeded only because of the element of surprise which accompanied it. That, however, did not prevent GHQ in its sudden but misguided enthusiasm ordering a repeat performance three days later on the remaining pillboxes the other side of the Triangle at Springfield and Winnipeg and at Glencorse Wood on the right. Whilst some success attended the former, the Germans were not caught again and our losses in infantry and tanks were high—twenty-four out of thirty-four machines being ditched or disabled.

Clearly further lessons would be necessary to achieve the success of 1918.

Footnotes

1 In his book The Tank in Action, undoubtedly the best book on the subject, the author D. J. Browne avers that Willard did not get into action because of the failure of his exhaust system. However, Lt Willard's Commander's Report states that he managed to get as far as Hillock Farm. Col Hankey CO of G Battalion comments that Willard followed on at the end of the column. Clearly Browne was unaware at the time that the tank had moved off and returned when he saw it still standing by the crossing.

2 The significance of the day's events were not lost on the Tank Corps General Staff, and one cannot escape the conclusion that the Report of Operations took pains not to diminish the role of the tank in the case of Triangle Farm where, in fact, the infantry took the initiative. It was after the war when there was a small publication boom that there were suggestions that Triangle Farm was not captured by a tank.

3 'Gorgonzola' stuck so fast that it was not removed until long after the war. In Capt Baker's papers (now in the Tank Museum) there is a photograph taken in 1920 exactly as it was left. With those papers is a photograph taken at the same time of another machine ditched by the bed of the Steenbeek evidently at the improvised crossing. This is annotated as being Kane's machine 'Galatea'. However, this was female and the one depicted is clearly male. The probability is that it is a photograph of Willard's 'Gloucester' which is known to have ditched on the way home. This machine also appears in an earlier photograph taken in 1918.

4 This gunner was the author's father Robert Owen Arscott who was taken to 61 FDS and then to the 1st Canadian Hospital at Etaples. He soon recovered the sight of one eye but lost the other and was discharged from the Army in May 1918. He died in January 1974 aged eighty-three.

Acknowledgements

The Tank in Action by D. G. Browne.

From Chauffeur to Brigadier by C. D'A.B.S. Baker-Carr.

The Tank Corps by C. Williams-Ellis.

Tanks 1914-18. Log book of a Pioneer by Sir Albert Stern.

History of G Battalion, Tank Corps.

Imperial War Museum

Fletcher—Librarian Bovington Tank Museum.

Regimental HQ Worcestershire and Sherwood Foresters.

Royal Regiment of Fusiliers (Warwickshire).

Diary of R. O. Arscott.

Peter Arscott was born in Bexhill-on-Sea in 1932. Now an architect living in Hampshire and practising in the Portsmouth area. His father was badly wounded in the Tank Corps in the Great War, and his brother was killed in RAF in 1940. Interests include Tangmere Military Aviation Museum, tanks in the Great War and local cask conditioned ales. He regrets never having asked his father “What did you do in the Great War?”

Further Reading: The Camera Returns No.26 by Bob Grundy and Steve Wall