General Sir Henry Wilson and the Disaster at Vimy - The German attack on IV Corps

- Home

- World War I Articles

- General Sir Henry Wilson and the Disaster at Vimy - The German attack on IV Corps

If anyone who has an interest in the Great War is asked name an event associated with Vimy Ridge, it is likely that 9 out of 10 will immediately think of the Canadian attack of April 1917. This brilliant feat of arms is something that will always be remembered, but there is far more to Vimy Ridge than this battle.

Throughout the First World War, the Germans were generally on the defensive and left it to the Allied armies to make attacks; there are of course a number of exceptions to this, but nevertheless this ‘tactical defensive’ was the position generally adopted. One of the exceptions took place in May 1916 when the Germans launched an assault on British positions at Vimy. The other noteworthy aspect of this attack is that it was one of the few occasions that Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Wilson was in command of troops in an operational capacity.

Henry Wilson

Lieutenant-General (later Field Marshal) Sir Henry Wilson is one of the most interesting Generals who served in the Great War. The BEF’s deployment to France in 1914 was largely planned by him. He was, however, disliked by many of his high ranking colleagues mainly due to his Machiavellian character: he was in regular contact with politicians and this led to him being distrusted within the Army.

Notwithstanding this, Wilson was to be appointed to be Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1918, which made him the professional head of the British Army. His promotion to this role in 1918 was very nearly de-railed during his brief assignment to an operational command on the Western Front in 1916.

Above: Lt-Gen Sir Henry Wilson

Despite their differences, General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the BEF in France and Belgium, accepted Wilson’s appointment to command IV Corps in December 1915. Wilson’s immediate superior was General Sir Charles Monro, who commanded the First Army. Wilson’s IV Corps was responsible for the section of front line between Loos and a point south of Givenchy. The southern part of this sector included Vimy Ridge. IV Corps held the southern sector of the First Army’s front.

In late March 1916, IV Corps was reduced in size and had under its control just the 47th (London) Division, the 2nd Division and the 23rd Division. One of the battalions in the 23rd Division was the 10/Duke of Wellington’s; a young corporal called J.B. Priestley - who was later to become a famous writer - was part of this battalion, he described the sector as ‘very sinister’.

Within a short time, Lieutenant-General Wilson learned he was to lose the 23rd Division which led him to remark “We shall be pretty thin if the Boch like to fight us”. The removal of these troops was part of the preparations for the Battle of the Somme, which would take place later in the year – this was to absorb many divisions of the BEF.

There was much mining activity in this sector, and on 3 May troops from the 47th Division exploded three mines using 42,000 pounds of explosive. Despite this, the sector remained relatively quiet. Later in May, Wilson was ordered to take over a further section of the line around Berthonval (near the site of the current Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery, making the frontage of his IV Corps about six miles long. This obviously put additional pressure on the two divisions under his command.

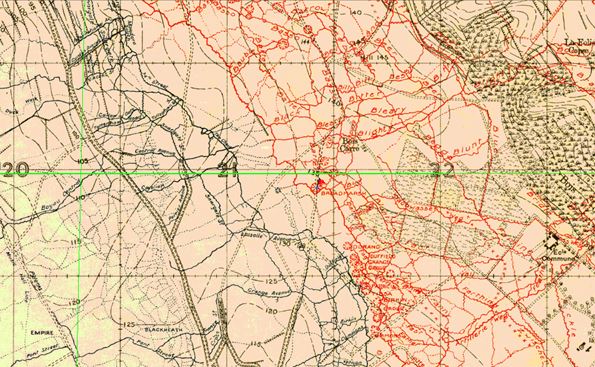

Above: Trench map of the Vimy sector.

The southern part of Wilson’s front was also the junction of the First Army (General Monro) and the Third Army (headed by General Allenby) – such junctions always needed careful coordination. Matters were further complicated for Wilson when, on 9 May, Monro went on a short leave, and so command of the First Army was temporarily in the hands of Wilson. The two divisions that IV Corps controlled also had their commanding officers absent at this period. Major-General WG Walker, VC of the 2nd Division was on sick leave and Major-General Barter (47th Division) was also on leave. The knock on effect was that two brigade commanders were acting as divisional commanders.

All this was of course unknown to the Germans who, troubled by the British mining, had decided to launch an attack to take the British mine shafts.

The German surprise attack

At 5 am on Sunday 21 May (Wilson was to note in his diary “another perfect summer’s day”) the Germans opened up with an exceptionally heavy barrage on the British lines which lasted six hours. Pausing at 11am (presumably to lull the British into thinking that no attack was forthcoming) the barrage recommenced at 3pm. Over the next four hours, an estimated 70,000 shells fell on less than one mile of the British front line. The barrage included tear gas which forced the troops enduring it (from the 1/7 and 1/8 and 1/20 Londons (47th Division) and 10/Cheshire) to don gas-masks.

The bombardment was not just on the front line, it reached as far back as artillery positions - some as far as eight miles from the trenches. It was possibly the heaviest German bombardment of the war so far; it destroyed trenches and cut off all communications. At 7.45pm the German attack began, which succeeded in capturing about 1,000 yards of trenches. Ordering forward units that were resting up to ten miles away, Wilson was otherwise powerless to act as not only had much of his infantry been taken away, but also a proportion of his artillery had also been removed.

Above: The Battle of Vimy Ridge, colour photomechanical print on light card after a painting by Richard Jack (1866 - 1952). The men are loading a 4.5 inch howitzer.

At a meeting the next day (22 May), Wilson decided to wait for reinforcement to his artillery, but any plans he had for an immediate counter attack were thwarted by the return of Monro from leave on that afternoon.

A counter attack was attempted on 23 May, but this failed, partly due to two battalions (1/Royal Berks and 22/Royal Fusiliers) from 99 Brigade (2nd Division) being unable to advance due to the German artillery barrage that was put down to stop the British attack. The Berkshires tried to inform the other attacking unit, 22/Royal Fusiliers, that they were unable to attack, but the message did not reach this battalion’s ‘B’ Company, which advanced on its own. Losses in these two battalions amounted to sixteen killed (Royal Berks) and thirteen killed (Royal Fus) plus numerous others who were injured. The majority of those killed from these two battalions are buried in plot II of Zouavre Valley Cemetery. (This cemetery can be fleetingly seen by those who pass this way on the A26 motorway. It lies in a valley opposite the Vimy Memorial.)

Above: Zouavre Valley Cemetery (CWGC)

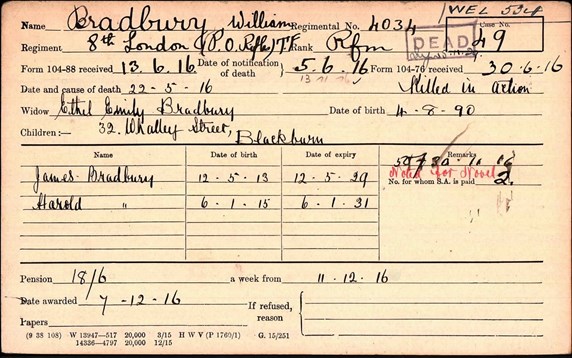

Total losses (killed, wounded and missing) between 21 and 24 May in this sector in British units came close to 2,500 with the 47th (London) Division being the worst affected. In the initial barrage and attack on 21 May, the1/5, 1/6, 1/7, 1/8 and 1/20 battalions London Regiment lost 169 men killed, with the 10/Cheshires and 8 Loyal North Lancs also losing a further 92 men killed. The hardest hit battalion was the 1/8 London (Post Office Rifles) which alone lost over 90 men killed in the initial bombardment. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of these fatalities have no known grave and are therefore commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the Missing.

Above: The Pension Record Card for William Bradbury of the Post Office Rifles. He is buried in Zouavre Valley Cemetery

Inevitably there were serious repercussions for the loss of a section of the front line. Not only did Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Wilson come close to getting sacked (or in the terms used at the time “degummed”) but Brigadier-General Kellett (who was temporarily in charge of 2nd Division) was never promoted. The failed counter attack also effectively ended the career of Major Rostron, who was commanding 22/Royal Fusiliers in the absence of its Colonel. Major Rostron (who had previously been affected by shell –shock) had a nervous breakdown during the action at Vimy and was sent home.

Aftermath

Immediately after the loss of the trenches, a debate took place amongst British High command, but it was decided that the effort needed to re-take the lost ground at Vimy (particularly in terms of artillery) would prejudice the build up to the Battle of the Somme, and it was decided to concentrate resources on the Somme. The front in this area became quiet again, and Wilson remained in command of the sector. It is possible that the disaster that had befallen IV Corps resulted in Wilson not being selected for Corps command for the Battle of the Somme. When Monro was transferred from First Army to be Commander-in-Chief in India in August, despite Monro recommending Wilson, he was not selected for this promotion. Wilson’s political manoeuvring paid off, however, as in November Lloyd George selected him to represent the Army on a high-powered mission to Moscow.

After the War

On 22 June 1922, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson (who had recently resigned from the army and who was now a Member of Parliament for North Down) unveiled the Great Eastern Railway war memorial at Liverpool Street station.

Above: The Great Eastern Railway war memorial at Liverpool Street railway station in London.

After completing the ceremony, he returned to his home at 36 Eaton Place. Having paid the taxi driver, and feeling for his keys, two men came up behind him, pulled out revolvers and shot at him. Injured by the first shots, rather than heading indoors, Wilson attempted to pull out his sword, but this gave his assailants time to fire further shots which proved fatal.

Bernard Spilsbury, a famous pathologist, arrived at the scene and carried out his examination of Wilson's body. His notes detail the injuries sustained:

Wilson was not shot after he had fallen. All nine wounds were inflicted when he was erect or slightly stooping, as he would be when tugging at his sword-hilt. The chest injuries were from shots fired at two different angles: one from the right to left and the other from left to right. Either would have proved fatal and produced death within ten minutes.

Above: The Memorial to Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson at Liverpool Street Station, London.

The two assassins were Reginald Dunne (also known as John O'Brien) and Joseph O'Sullivan (also known as James Connelly). Both were members of the IRA and aged 24 years old. O'Sullivan had lost a leg at Ypres in the First World War, and this had hampered his escape from the scene. Instead of fleeing on his own and making his own escape, Dunne stayed to try and aid O'Sullivan. Both men were captured at the scene.

Wilson's funeral was attended by Prime Minister David Lloyd George and members of the cabinet, plus many of his former army colleagues. Wilson was buried in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral.