German submarine UC-71: a brief history

- Home

- World War I Articles

- German submarine UC-71: a brief history

The wreck of a German mine laying submarine has recently been located and a 3D recreation of the vessel has been made which shows how it is currently sitting on the sea floor.

Below is a video created by Prof Chris Rowland and his team at the University of Dundee.

Nobody died during the sinking of this submarine in 1919. The 50m-long vessel is on the seabed, 22m below the surface off Helgoland, and was popular with divers before it was given legal protection.

What we know about the submarine

UC-71 was built in 1916 and during its active service between 30 March 1917 and 5 August 1917 was responsible for the sinking of 53 Merchant ships (16 others were damaged), the sinking of 10 auxiliary warships (plus one damaged) and the damage to another warship.

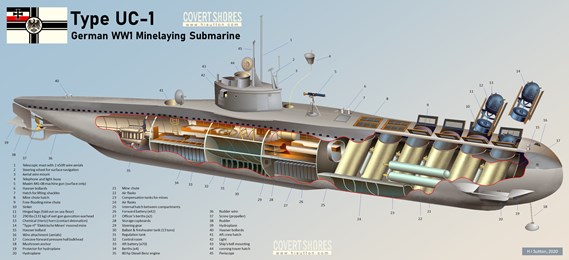

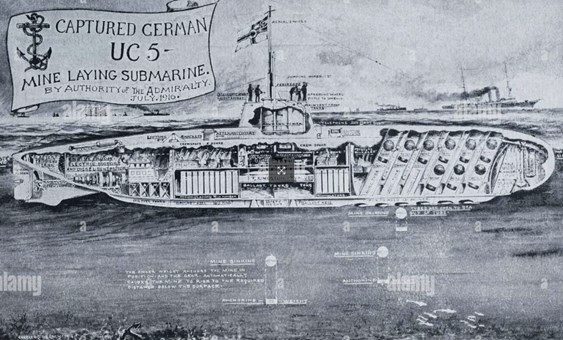

The submarine was one of 64 Type UC II submarines commissioned into the Imperial German Navy. They displaced 417 tons, carried guns, 7 torpedoes and up to 18 mines. The ships were double-hulled with improved range compared to the UC I type.

Above: Two German Type UC II submarines alongside Austro-Hungarian depot and accommodation ship AMPHITRITE at Gjenovic, Bocche di Cattaro, the southern Austrian base in the Adriatic Sea. One of the submarines is possibly UC 35.

Above and below: Images of German Mine-laying submarines

If judged only by the numbers of enemy vessels destroyed, the UC II is the most successful submarine design in history: According to modern estimates, they sank more than 1800 enemy vessels.

UC-71 had a maximum surface speed of 12 knots (14 mph) and a submerged speed of 7.4 knots (8.5 mph). When submerged, she could operate for 52 nautical miles at 4 knots; when surfaced, she could travel over 10,000 nautical miles.

The submarine was fitted with six 100cm (39 inch) mine tubes which can be seen on the wreck in the ‘open’ position, and carried eighteen UC 200 mines, seven torpedoes, and one 8.8 cm (3.5 inch) Uk L/30 deck gun. She would typically have 26 crew on board.

Whilst most of the vessels sunk by UC-71 were merchantmen, HMS Myosotis, an Arabis Class sweeping sloop was the only British warship to fall victim to the UC-71 (Myosotis was damaged on 9 September 1917).

Above: HMS Wisteria was the same class of ship as the Myosotis.

Because of the escalating losses to merchant ships, the British started using so called ‘Q-ships’ which were intended to lure the German submarines in before revealing themselves to be fully armed. One of the actions that UC-71 was involved in was the action against a Q ship which took place in the Bay of Biscay on 8 August 1917.

Q-ship action

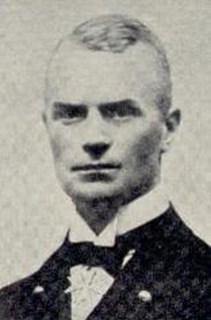

Commanded by Gordon Campbell (who had been awarded a VC for an action in 1916), and disguised as a collier (SS Boverton) HMS Dunraven spotted UC-71, commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Reinhold Saltzwedel.

Above left: Vice admiral Gordon Campbell, VC, DSO** (6 January 1886 – 3 October 1953)

Above right: Oberleutnant zur See Reinhold Saltzwedel (23 November 1889 – 2 December 1917)

Taken in by the disguise, Saltzwedel believed the ship was a merchant vessel and he submerged the German sub and approached HMS Dunraven before surfacing astern at 11:43 am and opening fire at long range.

A full account of the action between Dunraven and UC71 can be found in the London Gazette:

On the 8th August, 1917, H.M.S. "Dunraven," under the command of Captain Gordon Campbell, V.C., D.S.O., R.N., sighted an enemy submarine [UC-71] on the horizon. In her role of armed British merchant ship, the "Dunraven" continued her zig-zag course, whereupon the submarine closed, remaining submerged to within 5,000 yards, and then, rising to the surface, opened fire. The "Dunraven" returned the fire with her merchant ship gun, at the same time reducing speed to enable the enemy to overtake her. Wireless signals were also sent out for the benefit of the submarine: "Help! come quickly – submarine chasing and shelling me." Finally, when the shells began falling close, the "Dunraven" stopped and abandoned ship by the "panic party." The ship was then being heavily shelled, and on fire aft.

This painting of HMS Dunraven is by Charles Pears photograph Art.IWM ART 5130

In the meantime the submarine closed to 400 yards distant, partly obscured from view by the dense clouds of smoke issuing from the "Dunraven's" stern. Despite the knowledge that the after magazine must inevitably explode if he waited, and further, that a gun and gun's crew lay concealed over the magazine, Captain Campbell decided to reserve his fire until the submarine had passed clear of the smoke. A moment later, however, a heavy explosion occurred aft, blowing the gun and gun's crew into the air, and accidentally starting the fire-gongs at the remaining gun positions; screens were immediately dropped, and the only gun that would bear opened fire, but the submarine, apparently frightened by the explosion, had already commenced to submerge.

Realising that a torpedo must inevitably follow, Captain Campbell ordered the surgeon to remove all wounded and conceal them in cabins; hoses were also turned on the poop, which was a mass of flames. A signal was sent out warning men-of-war to divert all traffic below the horizon in order that nothing should interrupt the final phase of the action. Twenty minutes later a torpedo again struck the ship abaft the engine-room. An additional party of men were again sent away as a "panic party," and left the ship to outward appearances completely abandoned, with the White Ensign flying and guns unmasked.

For the succeeding fifty minutes the submarine examined the ship through her periscope. During this period boxes of cordite and shells exploded every few minutes, and the fire on the poop still blazed furiously. Captain Campbell and the handful of officers and men who remained on board lay hidden during this ordeal. The submarine then rose to the surface astern, where no guns could bear and shelled the ship closely for twenty minutes. The enemy then submerged and steamed past the ship 150 yards off, examining her through the periscope. Captain Campbell decided then to fire one of his torpedoes, but missed by a few inches. The submarine crossed the bows and came slowly down the other side, whereupon a second torpedo was fired and missed again.

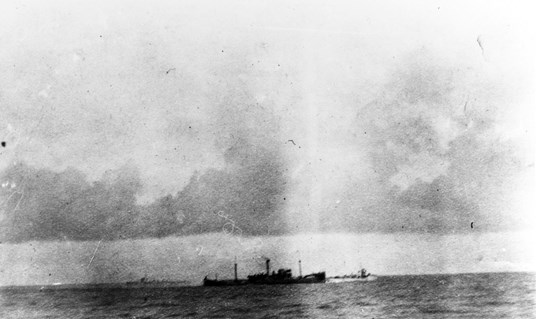

The enemy observed it and immediately submerged. Urgent signals for assistance were immediately sent out, but pending arrival of assistance Captain Campbell arranged for a third "panic party" to jump overboard if necessary and leave one gun's crew on board for a final attempt to destroy the enemy, should he again attack. Almost immediately afterwards, however, British and American destroyers arrived on the scene, the wounded were transferred, boats were recalled and the fire extinguished. The "Dunraven" although her stern was awash, was taken in tow, but the weather grew worse, and early the following morning she sank with colours flying.

The London Gazette (Supplement). 20 November 1918. p. 13694.

Above: The last photo of HMS Dunraven. Being assisted by H.M.S. destroyers ATTACK (right) and CHRISTOPHER following her action with the German submarine UC-71, off Ushant on 8 August 1917. despite efforts to tow her to port, the badly damaged DUNRAVEN sank on 10 August. Courtesy of Captain L.R. Leahy, USN, 1937. Catalog: NH 61073 Copyright Owner: Naval History and Heritage Command

Two VCs were awarded for this action. One to Petty Officer Ernest Pitcher and the other to Lieutenant Charles Bonner.

Petty Officer Pitcher was in charge of the 4-inch gun crew. When the magazine below them blew up the crew were blown into the air, but Pitcher and another man landed on mock railway trucks made of wood and canvas, which cushioned their falls and saved their lives. His VC was awarded by ballot of the gun crew

Above Pitcher (left) and Bonner

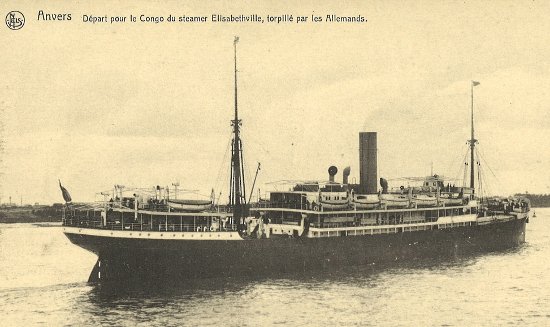

UC-71 went on to have an illustrious career. A month later the submarine was responsible for sinking the large Belgian passenger vessel Elisabethville.

In 2020, it was reported that a diary belonging to George Trinks, an engineer on the UC-71, had come to light. Trinks kept a record of daily life on board the submarine. His diary ends with the sentence: “No Englishman should step on the boat, that was the will of the crew and they achieved it.” This is important in the context of what likely happened to the submarine. To avoid the submarine being surrendered at the end of the war, it is almost certain the crew decided to scuttle her off Heligoland.

Above: An aerial view of Heligoland

The submarine attracted divers for many years until these wrecks were given heritage status and protection.

Above: The propeller of UC-71

Prof Chris Rowland, an expert in the 3D visualisation of underwater environments at Jordanstone College of Art and Design in Dundee, and Prof Kari Hyttinen, an expert in communication design, say they have evidence that the sub was deliberately scuttled.

During four hour-long dives, Prof Rowland and colleague Dr Florian Huber, an underwater archaeologist with Submaris, a scientific diving company, took thousands of photographs.

The above video labels 'hatches' - but these are the mine laying tubes. Both these videos courtesy of Prof Chris Rowland, University of Dundee and Submaris

Using state-of-the art cameras and high-intensity lighting to take stills and videos, the reconstructions were produced using a process called photogrammetry, with computers creating 3D renders using a sequence of overlapping images.

Article compiled by David Tattersfield

Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association.

Further Reading