Gott Strafe England

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Gott Strafe England

The 'withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line' of February 1917 enabled allied troops to occupy previously German-held towns and villages. The advance was not easy, the Germans left behind booby traps and other 'presents' that would today be termed 'IEDs' (Improvised Explosive Device). Following a 'scorched earth policy' they also reportedly cut down orchards and poisoned wells.

Less dangerously, but photographically more interesting they also left behind graffiti as described by Stanley Fisher who served in the 168th (Huddersfield) Battery RFA - part of 32nd Division. In this letter he describes the devastation caused by the Germans during their withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line:

“Most of the villages we have passed through have been gutted by the Germans and everything of value has been taken away. All the main roads have been mined, we have been held up at times until large craters were filled up and the guns could pass along. In one French town the civilians gave us a cordial welcome and gave us either tea or coffee to drink and they declined to take any payment. The Bosche cleared out on the Saturday and we were the first British soldiers to enter the town at 10am so I do not think we did badly. The place has been in the hands of Fritz since the commencement of the war. We were billeted in houses but the dirty blighter had broken every piece of furniture in the place we occupied. He had also written on the walls “Gott Strafe England”. They are a nation aren’t they? The town we are in is one from which Fritz had made a hurried exit, otherwise I have no doubt he would have gutted it as he has done the villages, where he has blown the churches up. In our journey through the villages we slept in holes or any sort of temporary shelter we could find. We are now in action on the outskirts of a ruined village so we set to work, cleaned up a cellar and put a top on it, and there we are living for the time being.”

Where was the town he describes? An internet search has revealed a number of possibilities

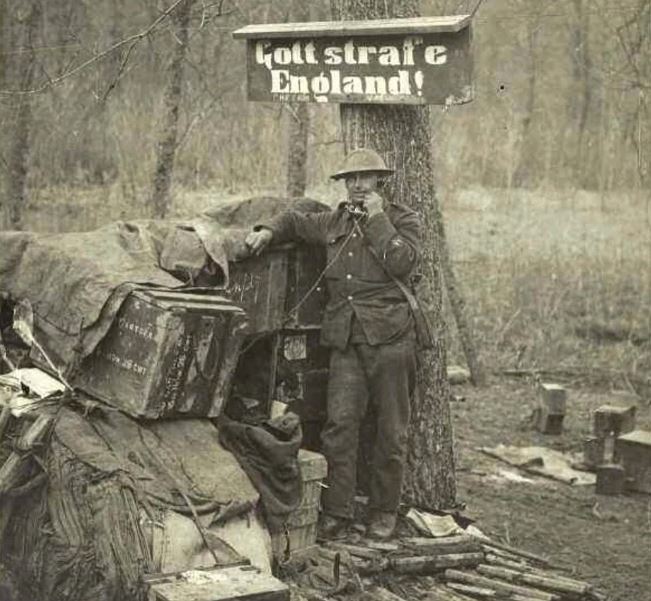

The above image (courtesy of www.andreruiter.nl) was taken in the village of Bucy-le-Long - this is near Soissons and miles away from Stanley's unnamed town.

Another view of the same building is shown here - this time as a 'Stereoscopic' image

Above image courtesy of Ian Ference (3D/stereoscopic images can be seen on the WFA's Sterescope pages)

But where did the phrase originate? It would seem that Gott Strafe England ("May God punish England") was a slogan used by the German army during the First World War. The slogan comes from the German poet Ernst Lissauer who was also the writer of the poem Hassgesang gegen England ("Hate song against England").

It was seemingly used 'officially' as seen in the postage stamp dating from 1915.

Source: www.onb.digital/result/BAG_15757675

The phrase was taken up by the British and used in cartoons against the Germans, as seen below

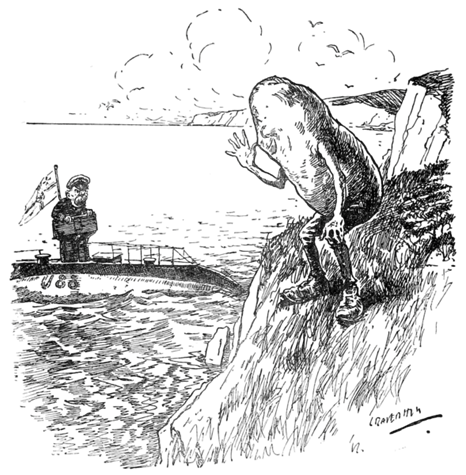

Punch Magazine, July 1917. Copyright© Punch Limited (Original Caption: The Tuber's Repartee. German Pirate. "Gott strafe England!" British Potato. "Tuber uber alles!" a British potato makes fun of a German u-boat commander at the cliffs of Dover during WW1)

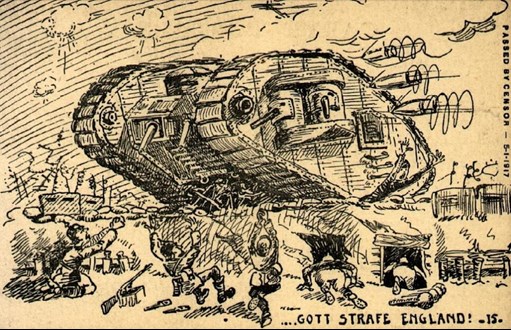

The French cartoonist M. Creté used it in this illustration (passed by censor 5 Jan 1917)

Source: www.bibliotheque-numerique.bibliotheque-agglo-stomer.fr

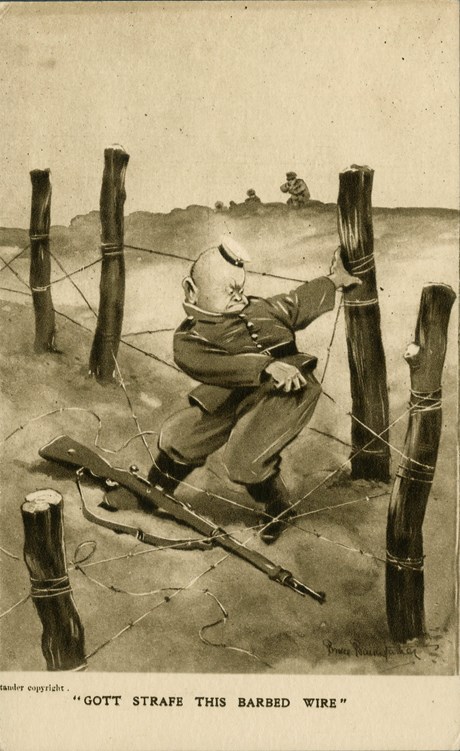

Even Bruce Bairnsfather took up the theme:

George Metcalf Archival Collection / CWM 19940078-032

Another image of the slogan used is this - courtesy of 'Drakegoodman' on Flickr

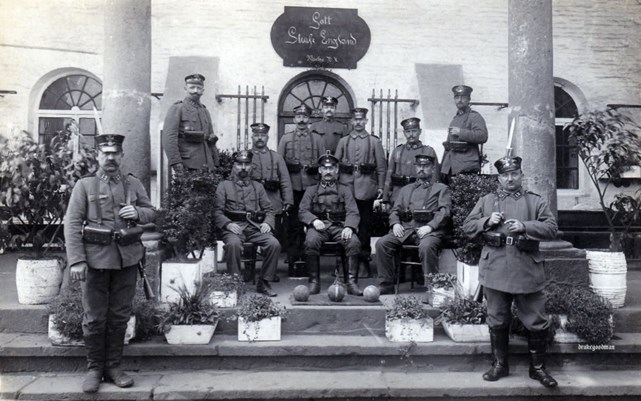

Bavarian infantrymen from the 12th Infanterie Brigade use their breadbag straps to support their large M.87 type ammunition pouches. "God punish England" being the sign in the top and centre of this posed photograph.

Other signs were used as a backdrop as shown below:

Image: www.reddit.com/r/TheGreatWarChannel

But what of the sign that Stanley talked about in his letter? Could the following be what Stanley Fisher observed?

The above is from the National Library of Scotland. The original caption reads 'A merry party in a newly captured village. The Huns [sic] bitterness does not upset the British Tommy.'

Finally there is the following image from the Imperial War Museum

The above - taken by John Brooke (ref Q 5022) - is captioned '"Gott Strafe England" and "Hier gehts fur Kaiser und Reich" inscriptions on the wall of a wrecked building in Nesle, March 1917.'

We know that the 32nd Division was at the southern end of the British line in February 1917 and advanced towards St Quentin. To quote from The Seventeenth Highland Light Infantry (Glasgow Chamber of Commerce Battalion): Record of War Service 1914-1918 by John W. Arthur and Ion S. Munro (Glasgow, David J. Clark, 1920) p.57

The road from Nesle to St. Quentin is a long and cruel one, but in these early days of 1917, it was to the 17th H.L.I. the pathway to glory. They were sweeping onwards in the track of the retreating enemy, with the glow of victory to strengthen their hearts and the blessings of a delivered people in their ears. The echoing trumpets of romance called to them from the Cathedral City, and their blood stirred to the call. These were the impressions that led them, in common with the rest of the Division, to surmount appalling obstacles, natural and devilish. They soaked in the snow, and froze in the keen blast; they starved and toiled on the way, but "stuck it," and their reward was the fall of Savy village. There was fighting all along the 50 mile front just then, and Savy did not loom very large in the chronicles of the time, but those who took part in its capture, and in the taking of the wood a mile beyond, knew that they had achieved the heroic.

It is therefore quite possible that the above image is what Stanley Fisher saw in February 1917.

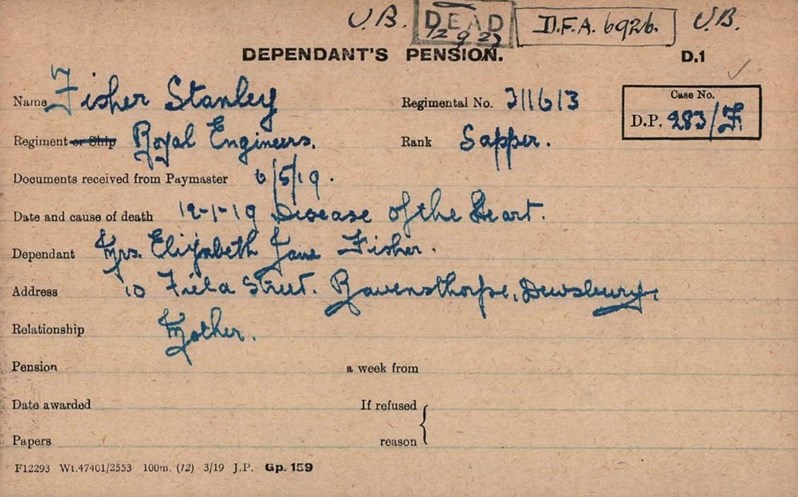

Stanley survived the war but in November or early December 1918 he fell ill and was sent to a military hospital at Rouen. After spending some time there he was brought back to England, being admitted to the Bermondsey Military Hospital in mid-December. It seems that Stanley’s condition deteriorated and a telegram was sent, resulting in his mother, who lived at 10 Field Street, Ravensthorpe, and his sister-in-law (the wife of his elder brother, Herbert) going down to London. They arrived on Thursday 8th January, but Stanley died four days later on Sunday 12th January from a heart attack. The newspapers, probably quoting a hospital report put his death down to over-exertion and exposure which together with influenza resulted in the ‘heart trouble’.

Above: Stanley Fisher was in the 168th Battery, RFA but subsequently transferred to the Royal Engineers as shown on the Pension Card below.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association