'Grandad’s War' by Prof. John Bourne

- Home

- World War I Articles

- 'Grandad’s War' by Prof. John Bourne

Both my grandfathers were born in 1880, both were coal miners and both had large families. My paternal grandfather (and namesake) John Bourne was, according to my father, a very decent man, but I have rarely shown any curiosity about him. My maternal grandfather, Jesse Sheldon, has always been the most intriguing absence in my life. I think my interest in him is entirely down to his being a soldier. I asked about him from an early age. I was told about the waxed moustache, the drinking, the lost medals, the lack of any photograph, the survival of his swagger cane, the bitterness about the lack of a war widow’s pension. This merely deepened my curiosity. In recent years I have been able to put his war back together.

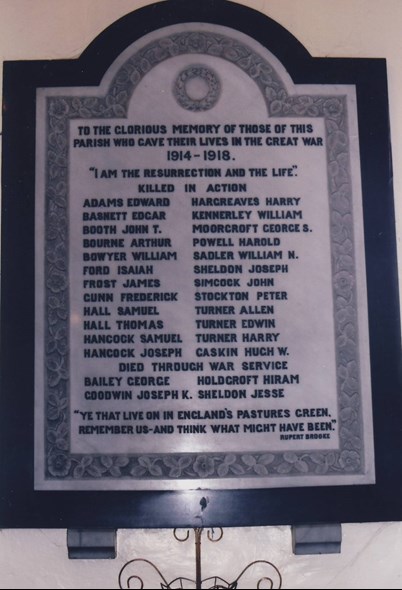

Above: The memorial in St Anne's Church, Brown Edge.

Jesse Sheldon was born in the village of Brown Edge, Staffordshire, on the road between Burslem and Leek, on 2 June 1880. He was the son of Josiah Sheldon, coal miner, and Caroline Sheldon (née Bowyer, later Sherratt). He was the third of six children. His siblings were Hannah, Richard, Annie, Eliza and John William Sheldon. The family were long-established in Brown Edge.

Caroline seems to have been a well-known character in the village. She was the daughter of Joseph and Sheba Bowyer. Her father was a boatman on the canals, delivering goods all over the country. He was a devout Primitive Methodist who attended the Hill Top Methodist chapel and preached there. There is a photograph of Caroline in Alan Pointon’s A Brown Edge History in which she is wearing a bonnet and shawl and holding a clay pipe. My mother and my Aunt Maud remembered her smoking a clay pipe. Jesse would almost certainly have gone to St Anne’s Church of England School, which opened in 1845. The school was closely associated with the Heath family, ironmasters, of Ford Green and Biddulph. William Jones was appointed Headmaster a couple of months before Jesse was born and remained in post for forty years. Jesse would have left school at the age of twelve, too young to go straight down the pit, but he seems to have become a collier as soon as he was legally able to do so. Mining was hard and dangerous, but also well paid by the working-class standards of the time, especially for men who dug out the coal (hewers), which Jesse was. My mother always believed that he worked at Chatterley Whitfield. He may well have done. This was the colliery at which most Brown Edge miners worked, but his army attestation form in 1914 shows him working at Sneyd Colliery, which was much closer to his home in Burslem.

Above: Sneyd colliery, Hanley (1887-1962). Image courtesy of www.staffspasttrack.org.uk

Above: Another view of Sneyd colliery. Image courtesy of www.stokesentinel.co.uk

Sneyd Colliery was opened in 1887 and remained in operation until July 1962. It was a very deep pit, some 1,800 feet. It mined household coal, manufacturing coal, steam coal and some ironstone. About 600 men were employed underground before the First World War.

Jesse married Louisa Davenport on 29 May 1904, Louisa’s 23rd birthday, at Burslem Parish Church (St John’s). They had six children in ten years. There is a big gap between the birth of my Uncle John (‘Jack’) (4 June 1904) and my Aunt Jennie (21 May 1908). This gap was filled by the birth and almost immediate death of another son, Joseph. My mother used to refer often to the ‘lost brother’ when she talked about her childhood. I never discussed this with my parents, but it now seems to me no accident that I bear the name of my mother’s brother and my sister bears the female version of the name of the brother who died. I found myself curiously moved by this belated recognition.

Louisa was heavily pregnant with Uncle Jack when she walked down the aisle. This rather shocked me when I discovered it, though not in the sense of moral outrage. It was quite common for working-class women to be pregnant before marriage during this period, a sort of trial run for their fertility, but on the understanding that the man would do the ‘decent thing’ if and when the need arose. Even so, giving birth six days after getting married is leaving it rather late, especially given the social stigma of births outside wedlock at this time. I remember my grandmother as being very old. I suppose all people look very old when you’re three, but she was a few days short of her 71st birthday when she died, younger than I am now. Six children in ten years and a life of poverty in the 1920s made for a hard life. It shows in the two photographs I have of her.

The connection between Jesse and Louisa was that he lodged with the Davenport family at 28 Navigation Road, Burslem.

Above: The junction of Navigation Road/Wycliffe Street in Burslem and was taken during the slum clearance. Image courtesy of www.stokesentinel.co.uk

It must have been rather crowded. In 1901, besides Jesse and Louisa, there was Louisa’s mother, Sarah Ann Davenport, a widow, described as a ‘charwoman’, and Louisa’s sisters, Georgina, Ann (‘Nancy’), Thirzaand Sarah (‘Sal’). There was also a child, William, described as a ‘grandson’. Louisa and Georgina were employed as ‘potter’s spongers’, Ann was a ‘mould runner’ and Thirza a ‘transferrer’. Sarah was still at school. Jesse and Louisa seem still to have lived at 28 Navigation Road after they were married, but my mother and Aunt Maud were born at No. 46.

By the time the First World War broke out Jesse was thirty-four and the father of five children, the youngest of whom, Maud (b. 8 July 1914), was less than a month old. Much ink has been spilled over the years by historians and others trying to explain why so many men (more than a million) volunteered for military service by Christmas 1914. It is not difficult to think of plausible explanations: unemployment, devilment, the desire to escape domestic boredom, peer pressure, patriotism, but I am not sure how convincing they are. I remember once saying to my old tutor, John McManners, that historians were ‘why’ people. We are expected to explain why things happen, but sometimes it may be necessary to accept defeat and say ‘I don’t know’. Why would a thirty-four year old, relatively well-paid man with a large family, working in an industry central to the war effort at home, decide to join the army when he was under no legal obligation to do so? (I doubt if Jesse would have been called up after the introduction of conscription, given his age and occupation. Grandfather Bourne’s age, occupation and family circumstances were identical to Jesse’s. He did not volunteer and he was not conscripted.)

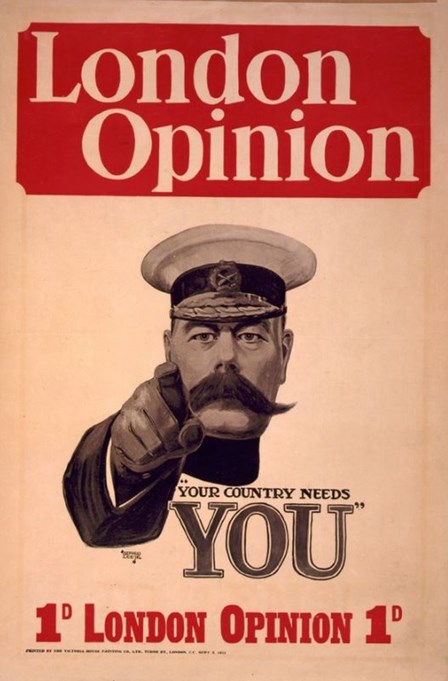

Lord Kitchener’s original Call-to-Arms, made on 7 August 1914, was restricted to men aged 19 to 30.

Above: A slightly later poster (from September 1914) so not the one that Jesse Sheldon would have responded to.

The maximum age limit was raised to 35 on 27 August and became publicly known the next day. Jesse volunteered at Burslem Town Hall on 29 August 1914, virtually his first opportunity to do so. Whatever his motives, they were clearly compelling. I know that Aunt Maud never forgave her father for abandoning his family and eventually leaving them in poverty. I suspect she felt that all men were basically ‘unreliable’. I only recently discovered that his younger brother (by eight years), John William, also volunteered and served in the same battalion before transferring to the Machine Gun Corps. A nephew, Herbert Sherratt, son of Jesse’s oldest sibling, Hannah, volunteered in February 1915 and was awarded the Military Medal in 1917 while serving with 189 Brigade RFA.

One of the mysteries about Jesse was not knowing what he looked like, except for the memory of his having a waxed moustache. But on his attestation form he was described as 5’ 7½” tall, weight 138 lbs, chest (when fully expanded) 37½”, complexion sallow, eyes brown, hair brown. He had a small blue scar on his left elbow, a long blue scar on the back of his neck and a big scar on the inside of his right leg. These are the characteristic scars of a coal miner. His religious denomination was stated as ‘Wesleyan’. (My mother was always insistent that she was a ‘Wesleyan’ and not a ‘Methodist’.)

Jesse was given the service number 14755 and posted to the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion of the North Staffordshire Regiment in Guernsey on 4 September 1914. This is a bit of a mystery. As an early volunteer he might have been expected to join the 7th or 8th Battalions, which had been specially raised for the war. The 4th Battalion existed before the war. Jesse was transferred to the 11th (Reserve) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, which was formed in Guernsey, on 28 November 1914. This unit was posted to Alderney in February 1915 and to Darlington in July 1915. The war began in earnest for Jesse when he was transferred to the 7th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment on 14 September 1915. (His brother John, although he had a higher service number, 14957, landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 13 July 1915with the 7th Battalion and took part in the attack on Sari Bair in August.) Jesse was part of a large draft of reinforcements made necessary by losses sustained in the August battles. He embarked for the eastern Mediterranean from Avonmouth Docks, Bristol. No matter why Jesse volunteered, he was clearly volunteering to fight Germans. On 29 August 1914 Britain was not at war with the Ottoman Empire. It is a moot point what early volunteers like Jesse made of being sent to fight the Turk, who – unlike the German – was clearly no threat to hearth and home.

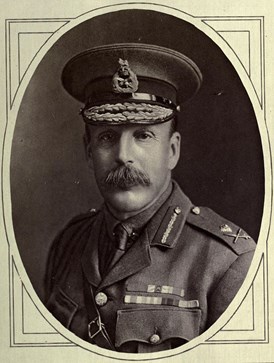

Jesse served at Gallipoli for four months. After the failure of the August offensives the war on the peninsula became moribund. No one seemed to know what to do: send out yet more troops and have another attempt at a decisive breakthrough; or pull out. Things drifted. The commander of Jesse’s division, the 13th, Major-General Stanley Maude, wrote in his diary that there was ‘nothing very special going on’.

Above: Major-General Stanley Maude

This does not mean that the troops had a cushy time. Quite the contrary. Conditions on Gallipoli were much worse than on the Western Front in France and Belgium. There was no proper trench system. The Turks held the high ground and had much better artillery. This meant that nowhere on the peninsula was safe. Clean water was in short supply for both drinking and washing. Thirst was a major problem. The dead were difficult to bury in the rocky ground and often had to be left to rot in gullies and ravines. This produced a plague of flies that spread disease. Intestinal diseases such as diarrhoea, typhoid and dysentery were a major problem in the summer. In the winter, exposure, hypothermia, trench foot and frostbite became major issues. Malaria was a problem throughout. Sickness rates were very high, far higher than in France, and medical evacuation was always difficult. The peninsula was described by one contemporary as resembling a ‘gigantic morgue and open latrine’.

If this was not bad enough, at the end of November the 7th Battalion’s trenches were flooded during an apocalyptical rainstorm, which was followed by a snowstorm and severe frost. Supplies of winter clothing were entirely inadequate. Sickness rates rocketed and there is evidence that morale began to plummet. It was obvious to the men that the campaign was not going to end well and that they were continuing to suffer for nothing. Fortunately, relief was at hand. General Hamilton, the Commander-in-Chief, was sent home in October. His replacement, Sir Charles Monro, was asked by Kitchener to recommend whether we should stay or go. There seems little doubt that the answer Kitchener received was not the one he wanted.

Above: General Sir Charles Monro

Monro was a leaver. He made an inspection of all the beachheads and as he moved down the peninsula he was heard to say ‘curiouser and curiouser’. Kitchener did not take Monro’s advice until he went out to look for himself and even then he only agreed to the evacuation of the Suvla Bay and Anzac positions. The 7th North Staffords were at Suvla Bay. They were brought out on 9/10 December in an operation that General Maude described as a ‘masterpiece’. They spent Christmas on the Greek island of Lemnos. That ought to have been that, but it wasn’t.

The British government decided on 23 December to evacuate the last remaining beach-head at Cape Helles. To his dismay, General Maude was told on 27 December that in order to facilitate the evacuation, troops of 39 Brigade (including the 7th North Staffords) would have to return to the peninsula. The North Staffords found themselves holding a position called Fusilier Bluff. On 7 January 1916, two days before the scheduled evacuation, the position was violently attacked by the Turks. Although the attack was beaten off after six hours, casualties were heavy - forty-five men, including the commanding officer, Colonel Walker, were killed and three officers and 106 men wounded.

Above: Lt-Col F H Walker

It was the worst single day experienced by the battalion in the entire war. The evacuation took place on 8/9 January, but the North Staffords were unable to bring out their dead, none of whom has a known grave. Even this wasn’t quite the end of the Gallipoli affair. It seems that a number of soldiers in the battalion had quit their posts during the Turkish attack to find shelter on the beach. Seven of them were tried by court martial in Egypt in January and February 1916 on charges of ‘cowardice’. They were all found guilty and sentenced to death, though none of the death sentences was actually carried out.

The 7th North Staffords were evacuated to Egypt, but on 8 February 1916 orders were received for the 13th Division to move to Mesopotamia. They disembarked at Basra on 27 February 1916. The 13th Division was the only British division to serve in the Mesopotamia Campaign. The war in Mesopotamia had been launched by the Indian government, originally with the aim of securing the oil facilities of Abadan at the head of the Persian Gulf, but emboldened by easy success the decision was taken to press on into the interior and take Baghdad. This went well to start with, but eventually the largely Indian army was pushed back and besieged in a bend of the Tigris at Kut-al-Amara. Several attempts were made to relieve the Siege of Kut. The conduct of these attempts by the commander of III Tigris Corps, Major-General George Gorringe (‘Blood Orange’), was unimpressive.

The 13th Division was involved in the third attempt, which took place between 5 and 22 April 1916. This was one of the most costly periods of the war for North Staffordshire, though it has not had the same impact on popular memory as single-day disasters like 13 October 1915 (the attack on the Hohenzollern redoubt) or 1 July 1916 (Gommecourt). The relief failed and Kut surrendered on 29 April 1916. This was one of the most humiliating defeats in British imperial history, up there with Yorktown and Singapore.

Jesse was wounded on 19 April 1916. When I read in his file that he had suffered a gunshot wound to the ankle an unworthy thought crossed my mind: that this might have been a self-inflicted wound (SIW). But I soon dismissed the idea. The army medics were not stupid and would have picked up a SIW.

Above: Wounded Turks being tended at an Indian advanced dressing station after the action at Tikrit on the Tigris river, Mesopotamia, November 1917. During the assault on a well dug-in enemy British, Sikh and Punjabi troops distinguished themselves. (IWM Q24439)

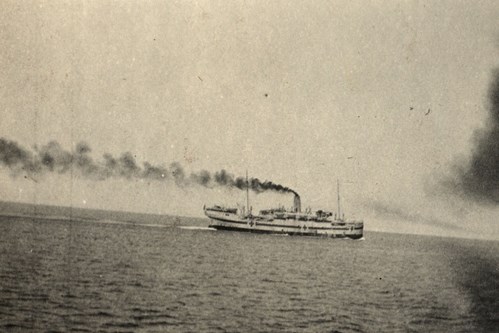

On reflection, I decided that it was a classic machine gun bullet wound. Machine-guns were usually sited to flank any attack. They were also kept very close to the ground to minimise their visibility. They produced a stream of bullets at ankle height. Jesse’s wound was serious enough for him to be admitted to hospital in Basra on 26 April and then invalided to India on HMHS Takada, a British India Steam Navigation Co. vessel, on 28 April.

Above: The HMHS Takada in the Persian Gulf bound for Bombay taken from the HMHS Gascon. Image courtesy of www.nam.recollect.co.nz

He was in hospital in India for some time and did not return to Mesopotamia, from Karachi, until 28 December 1916, arriving in Basra on 2 January 1917. He rejoined his unit on 1 February 1917.

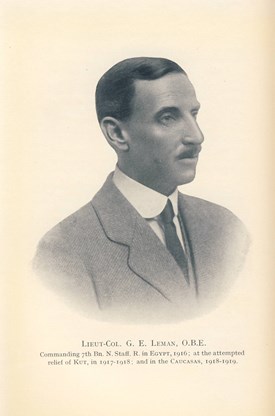

By the time Jesse returned his old divisional commander, General Maude, was now commander in chief. Maude was an outstanding soldier, known as ‘Systematic Joe’. He set about a fundamental re-organisation of his forces, focusing on improved training, food, living conditions and medical services. The 13th Division was now commanded by Major-General Walter Cayley, another excellent soldier. The 7th Battalion’s original commanding officer, Thomas Andrus, who had been wounded at Gallipoli, was now in command of 39 Brigade. Lieutenant-Colonel G.E. Leman was CO of the 7th North Staffords.

Above: Brigadier-General Thomas Andrus

Above: Lieutenant-Colonel G.E. Leman

Jesse was back in time to take part in the final attack of the Battle of Kut, known as the Capture of the Dahra Bend (9-16 February 1917), which forced the Turks to surrender the town.

Above: The Dahra Bend, on the River Tigris just west of Kut. From 'The War in the Air, vol 5' by HA Jones (1935)

Turkish forces were then pursued as far as Baghdad, which was taken on 11 March 1917, the first unambiguous British victory of the war. General Maude died of cholera in Baghdad on 18 November 1917, allegedly after drinking infected milk at a performance of ‘Hamlet’ in Arabic! He was succeeded by General Sir William Marshall, another fine soldier, who eventually brought the Mesopotamia campaign to a triumphant conclusion in 1918.

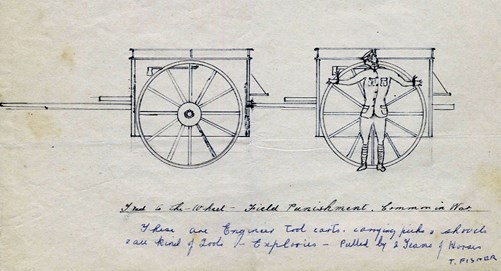

On 10 October 1917 Jesse found himself in trouble. He was put under close arrest and tried by Field General Court Martial four days later for the offence of ‘When on active service Neglect to the prejudice of good order and Military discipline. Then one of a double sentry allowing the other sentry to leave his post without being regularly relieved’. He was found guilty and sentenced to three months Field Punishment No. 1. This was a pretty unpleasant punishment, especially in a climate like that of Mesopotamia. It was used in the absence of military prisons in the field. Men would be tied to a static object such as a post or a gun wheel for up to two hours a day.

Above: Field Punishment No. 1. Image courtesy of www.roadstothegreatwar-ww1.blogspot.com

This was controversial at the time and was often referred to as ‘crucifixion’. The sentence seems unfair and excessive. After all, Jesse did not leave his post. It was the other bloke. And Jesse was in no position to order the other bloke to stay as he was not superior in rank. FP No. 1 was normally limited to a maximum of 21 days, so unless the sentence was incorrectly recorded as three months instead of three weeks, it appears to be illegal. The sentence was confirmed by Brigadier-General Andrus, but Lieutenant-General Marshall, rightly in my view, set aside both the finding and the punishment.

Jesse’s second bit of bother captures the image I formed of him through talking to my Aunt Minnie and my Great Aunt Nancy. On 14 January 1918 he was awarded seven days Field Punishment No. 2 (which did not involve being tied to anything) on charges of ‘improperly dressed’ and ‘insolence’. He was, after all, a miner, and miners are famous for their independence and argumentativeness. By this time he had also already begun to suffer heart problems, which may also have made him a trifle ratty.

During the period 16 December 1917 to 14 March 1918 Jesse was employed, at extra pay, with 72 Field Company Royal Engineers. I should imagine that this involved a lot of heavy lifting, which probably didn’t do his heart much good. On 4 April 1918 he went sick and reported to a Field Ambulance. They obviously didn’t like the look of him and he was sent down river to the 3rd British General Hospital at Basra. His examination revealed his heart to be ‘hypertrophied and dilated’, with aortic diastolic and mitral presystolic murmurs, leading to shortness of breath and palpitations. On 24 May he was invalided to India on board AT [Ambulance Transport] Varsova.

Above: AT Varsova. Image courtesy of www.wartimememoriesproject.com

He arrived in India on 31 May 1918 and was sent to the famous military hospital at Deolali (as in ‘Doolally tap’) and then to Belgaum. You sometimes get the impression from the telly that medical provision during the First World War had not progressed much since the Crimea. This is nonsense. It was, eventually, and within the limits of contemporary knowledge, ‘state of the art’. By 1917 there were more doctors serving with the armed forces in the field than there were in the United Kingdom. Jesse got good treatment and an (unfortunately) accurate diagnosis. The diagnosis was Valvular Disease of the Heart (VDH). He stated that he had not suffered heart problems before joining the army and a medical board, held at Poona on 5 August 1918, was clear that his condition was the result of ‘active service and climate’. The board was equally clear that Jesse was incapable of further military service. In answer to the question ‘Is the disability in a final stationary condition?’ the examining doctor wrote ‘No, will get worse’. This was not only perceptive but also prophetic. The level of disability was estimated at 60 percent and Jesse was granted a pension of 16s 6d, with an allowance ‘for five children’ of 14s 6d. This award was for 39 weeks and was due to expire on 29 July 1919.

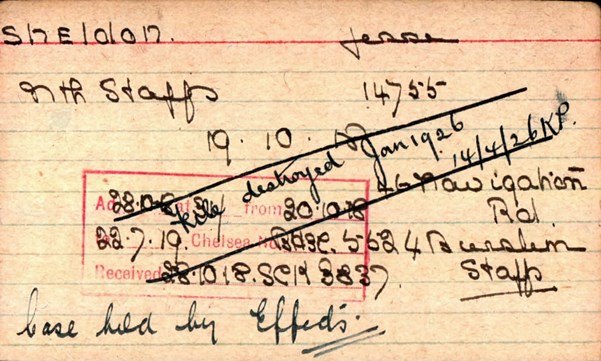

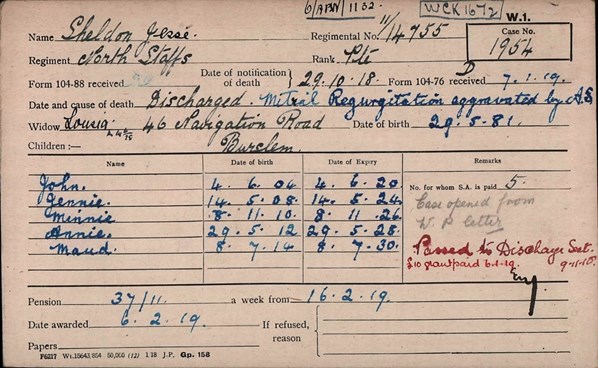

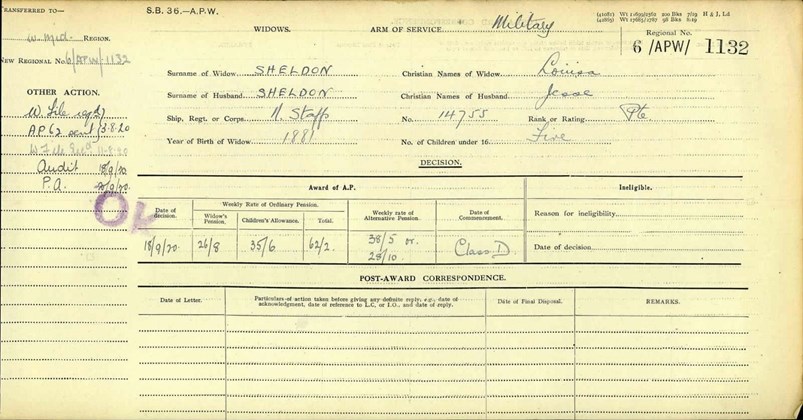

Above: Pension Cards from the WFA's Pension Card archive relating to Jesse Sheldon's pension claim. Note 6/APW/1132

Jesse left Bombay on board HMHS Glengorm Castle on 27 August 1918. He arrived in Alexandria on 8 September and Marseilles on 15 September. The record is silent, but he may have been disembarked at Marseilles and brought to the Channel coast by train. On his return to England he was admitted to the Graylingwell Naval Hospital at Chichester. He was formally discharged from the army at Whittington Barracks, Lichfield, on 19 October 1918 and dropped dead in the backyard of 46 Navigation Road ten days later. My mother was adamant that he had a military funeral. There is no record of this, but it seems entirely plausible. I could find no report of his death or funeral in the Staffordshire Sentinel, but my friend Su Handford, Queen of the Newspaper Search, found the following in the In Memoriam section of the Sentinel on Monday, 31 October 1918. It says:

‘SHELDON – In loving memory of Pte. Jesse Sheldon, N.S. Regt., of 46, Navigation Road, Burslem, who died October 29th, 1918, aged 38.

“Absent from us, but sweet memories cling”

Fondly remembered by his Mother, Stepfather, Brothers and Sisters and all relatives.’

This was obviously put in by Jesse’s Brown Edge relations, two days after he died. There is no mention of his wife and children, which I found interesting, to say the least. He is remembered on the war memorial in St Anne’s Church, Brown Edge, but not on his local war memorial in Burslem, the Barnfields Memorial, even though his next-door-neighbour, at 48 Navigation Road, Albert Hancock, is.

Jesse’s grave in Burslem Cemetery has a Commonwealth War Graves headstone.

Many of my relatives are buried in Burslem Cemetery, but none of the family graves mentions my grandmother on their headstones. Jesse died before CWGC headstones became available. He was not in the army when he died. The grave is a private one and was paid for by Louisa. The headstone would have been erected later. I believe that Louisa is buried in Jesse’s grave, but the CGWC made a decision that the names of relatives would not be allowed on their headstones. It may simply be that she chose to be buried in a grave she had paid for, but perhaps touching that she wished to be buried with Jesse.

One of the cardinal beliefs in my mother’s family is that my grandmother was denied a war widow’s pension. This drove feelings of bitterness, reflected in my grandmother’s refusal to allow any of her children to buy a Poppy. The release of the Pension Ledger records makes it clear that this belief was false. A widow's pension was awarded from 6 February 1919 at 37s 11d per week (which was the correct rate for a widow and five children under the 1918 warrant). On 18 September 1920 a decision was made for an Alternative Widows Pension. This showed that she had 62s 2d per week in total for her and five children whereas the alternative amount was 28s 10d or 38s 5d.

Above, the ledger (6/APW/1132) for the 'Alternative Widows Pension' (From the WFA's Pension Record Archive).

It looks like she was eligible to claim for an Alternative Widows Pension but, as it was less than the normal pension, the normal pension was paid so that she got the higher amount. The element of the pension for the children would typically have been paid until they reached the age of 16; the widow’s element would have continued until her death in May 1952.

I am dubious about the belief that underpins the search for ancestors in programmes like Who Do You Think You Are?. I have always known who I am, for good and ill and it is certainly both. This is not my story. It is Jesse’s and in its way it is a remarkable one. A man who had probably never before left North Staffordshire, whose life was bounded by a mining village and a pottery town, who had spent his working life in the dark, deep in the ground, found himself bound for the ‘Middle Sea’, the world of the Pharaohs, Ulysses, Troy, the Arabian Nights and the Bible. And also a world of violence, death, killing, fear, suffering and tedium. What tales he could have told had he survived. Lady Cynthia Asquith, femme fatale of the posh set, wrote in her diary in 1915 that ‘normal life’ had been ‘interrupted by History’. This was the case for an entire generation. The consequences can still be felt.

J.M. Bourne

(I wish to acknowledge the help and expertise of Su Handford and Craig Suddick in reconstructing my grandfather’s war.)

John Bourne taught History at Birmingham University for thirty years before his retirement in September 2009. He founded the Centre for First World War Studies, of which he was Director from 2002 to 2009, as well as the MA in British First World War Studies. He has written widely on the British experience of the Great War on the war front and the home front. He is currently completing a multi-biography of Britain’s Western Front Generals. He is a Vice President of The Western Front Association, a Member of the British Commission for Military History, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Hon. Professor of First World War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton.