Just another ordinary soldier?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Just another ordinary soldier?

A CWGC stone, of Welsh slate rather than the usual Portland stone, marks the final resting place of Charles Norris – lying at the edge of a Swansea parish church cemetery, and bearing witness to a short life spanning three continents.

Above: St Peter’s Church, Cockett, Swansea

Sources on ancestry.co.uk suggest that Charles Norris was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 18 August 1893, the son of Charles Foxcroft [born 1866], and Harriet [nee Waldron, born 1875]. His father died when Charles was very young, and Harriet remarried. Her second husband was William Norris [born 1871], with Charles taking his stepfather’s surname. UK Census entries for 1911 and 1921 give some indication of Charles’s movements whilst growing up. Three siblings were born in Buenos Aires [1895-1899]. On returning to Britain three more were born in Portsmouth [1901-1906] and two in Devonport [1908-1910]. By 1911 the family had settled in Swansea, and another three children followed between 1911 and 1921.

The census of April 1911 has Charles living with his parents and eight siblings at 9 Lynn Street, Cwmbwrla, Swansea. He was 18 years old and employed as a general labourer in a fuel works. Sometime between April 1911 and 1914 Charles emigrated to Australia, and it was there, in Oaklands, South Australia, that he volunteered for the Australian Imperial Force in January 1915.

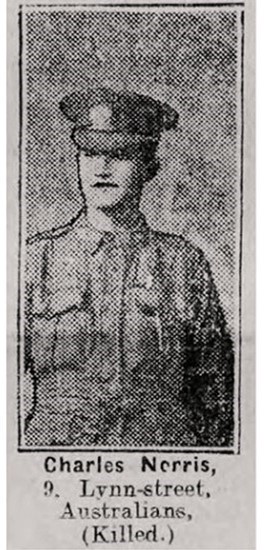

Above: a local newspaper illustration of Charles Norris

His Attestation Paper, included in his Army record, cannot be taken at face value. His birthplace is wrongly recorded as Swansea, but he had only lived in the town for four years at most. His age was recorded as 20y 5m, not 21y 5m. Next of kin details were for a brother in Swansea, suggesting that Charles travelled to Australia on his own. These details were later amended in red ink to show a wife in Australia. His occupation on enlistment was fireman. Physical examination stated he was 5 ft 7½ in tall, weighed 140 lb, with brown eyes and dark hair.

Charles underwent training for a month before being attached to 5th Reinforcements, 12th Infantry Battalion in February 1915. Army records suggest that he was not ideally suited to the discipline of army life, with episodes of being drunk and disorderly and being absent without leave [AWOL], resulting in camp punishment and loss of pay, in the first few weeks of his army career. A comment on his general character at this time consisted of one word – “bad”.

The 12th Infantry Battalion was active in the Dardanelles campaign from April to December 1915, and Charles arrived there in June. On 6th August he was wounded, resulting in his evacuation from the front line to the Allied base at Moudras on the island of Lemnos. The wound was described as “..bullet came through thigh and also hit left forefinger”. In early September he embarked for England on SS Reiva, disembarking at Plymouth on 10thSeptember, and was admitted the following day to the County of London Military Hospital, Epsom with the comment “severely wounded”.

Over the next few weeks Charles was recovering from his wounds, with an examination in late November noticing “Painful scar on thigh. Stiff joint of first finger of left hand. End of finger anaesthetic. Anaesthesia of back of thigh”– all suggesting continuing nerve damage from his wound. The medical board concluded that he was permanently unfit for active service but fit for home service. The extent of his inability to earn a living was assessed as being “¼ [quarter]”.

Charles had still not taken to army discipline with a further incident of being AWOL in November 1915, when he took the opportunity to visit family in Swansea. In March 1916 he was docked pay and admitted to a hospital in Cambridge for specialist treatment of an avoidable disease.

By late December 1915 Charles was in Weymouth, at the No 2 Command Depot – an Australian Army facility housing servicemen assessed as unfit for further active service and awaiting repatriation to Australia [1]. It was here that he suffered the accident that resulted in his death. Late evening of 4 May 1916 he was seen by a passer-by crossing a street in Weymouth, when a car with minimal lights, due to blackout regulations, came round the corner. Charles neither saw or heard the approaching car, and the driver did not see Charles until it was too late. He was knocked down and trapped under the car. The driver and passer-by managed to get him into the car and take him to Sidney Hall Military Hospital, but he was deeply unconscious on arrival at 11:10 pm and died twenty minutes later. Cause of death was given as fractured base of skull and, on 6 May, the inquest jury verdict was that “..death was caused by accident and no blame is attached to any person”.

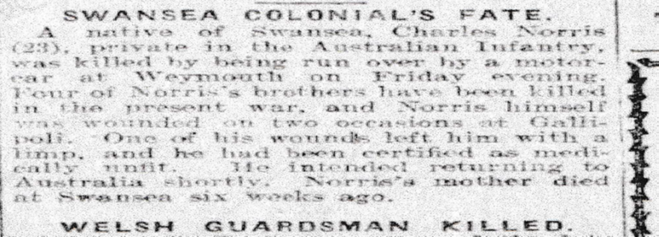

Charles Norris’s death was reported in the local South Wales papers, with a small entry entitled “Swansea Colonial’s Fate” appearing in The Cambria Daily Leader on 8thMay1916.

Above: Cambrian Daily Leader report from 8 May 1916. National Library of Wales Archives

This must have added to the family’s pain as the reporting was inaccurate, and a letter of correction from Charles’s father appeared in the next day’s issue.

“Sir, - With reference to the statement in your paper last night I beg to inform you that the late Charlie Norris, Australian Imperial Forces, killed on the 4th in Weymouth through a motor car accident, has not four brothers killed in this war, nor is his mother dead. A son of mine was killed two years and nine months ago by a traction engine in Cwmbwrla, and two sons are serving in HM Navy and are alive as far as I know. I think it my duty to correct the error. The body of the late Private C Norris arrived on Monday night from Weymouth and is in my house. The funeral, with military honours, takes place on Thursday, leaving at 3pm for Cockett. – Yours, etc. W. Norris.”[2]

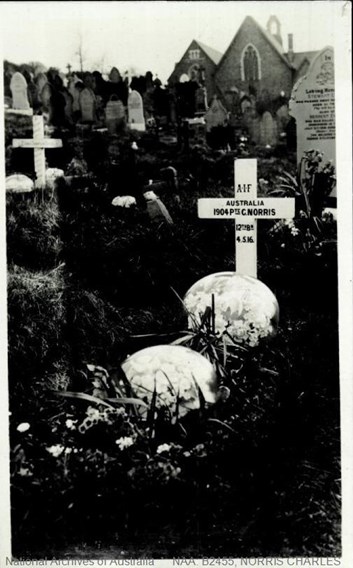

Above: Charles Norris’s grave in St Peter’s cemetery – as it was in in 1917 and in 2020

Even in death Charles Norris continued to confuse. The Australian Imperial Forces were unaware that he was a married man. A letter received on 24 May 1916 from Muriel Gladys Norris of Sydney, New South Wales, enquired about her husband as she had seen reports in the Sydney Morning Herald that he had been killed. She had received “..no word from home in Swansea”. It took an exchange of letters and the production of a marriage certificate before army records were amended in July 1916 to include his wife as next of kin. A copy of the marriage certificate was not attached to the army record, but Australian marriage records confirm that Charles Norris married Muriel Gladys Hobbs in Adelaide on 18 March 1915 – after enlistment and before embarking for the Dardanelles. Nothing else is known of Muriel Gladys – either before her marriage to Charles or after his death. An Army letter, dated 12 July 1916, comments “Private Norris enlisted as a single man, but a British Army form to hand contains information that the soldier leaves a widow”. Unfortunately, the matter took some time to be cleared up as, in 1922, his war medals, memorial plaque and scroll were initially all sent to Swansea. They had to be returned to the authorities before being passed on to his widow.

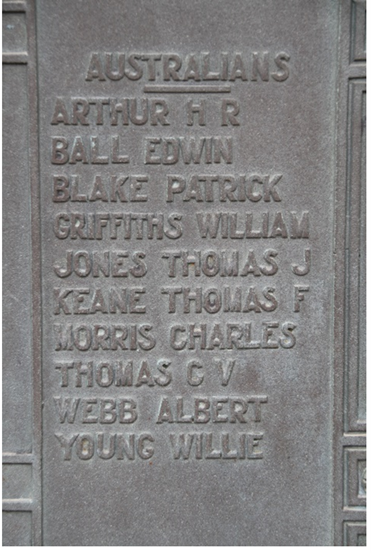

Charles Norris was buried on 11 May 1916 at St Peter’s Church, Cockett, Swansea. Today there is nothing to indicate other family members buried nearby. His name does not appear on the local Fforestfach War Memorial on Carmarthen Road. He is commemorated on the Swansea War Memorial on Oystermouth Road, but his surname has been misspelt as Morris. He was one of countless thousands with no specific act of bravery to mark their sacrifice. This article will, I hope, ensure that his name will not be entirely forgotten.

Above: Charles Norris’s misspelt name on Swansea War Memorial.

Article contributed by Arwel Davies

References.

[1] Beckett, R. (2020). Keeping up the Strength. The Australian Imperial Force in 1918. Stand To! The journal of the Western Front Association, 118, pp. 40-45.

[2] The Cambria Daily Leader, 8th May 1916 & 9th May 1916.

Acknowledgment.

I am deeply grateful to staff at the National Archives of Australia for help with accessing Charles Norris’s army records – without which this article could not have been written.