Leeds Pals Memorial

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Leeds Pals Memorial

The Yorkshire Dales can be one of the most picturesque spots in the UK. They can also be cold, windswept, wet and inhospitable.

On the road out of Masham (pronounced Massam), which is a small town north of Ripon, are a couple of reservoirs, Leighton and Roundhill. The first of these – Roundhill – was commissioned by Harrogate Corporation in the very first years of the 20th Century.

During the construction an industrial railway to bring in materials for construction was needed, and a 2 ft gauge railway was built in the 6-mile valley from the north end of Masham railway station to Roundhill. A transhipment yard was located to transfer freight between the narrow and standard gauge lines. The line opened in 1905.

Leeds Corporation started another reservoir called ‘Leighton Reservoir’ adjacent to Roundhill. Work on the second site commenced in 1908.

Roundhill Reservoir was completed in 1913, at a cost of £500,000. Work was undertaken by large numbers of navvys. They were housed at nearby Breary Banks. At its peak, Breary Banks was home to over 700 workers and their families housed in rows of huts organised into streets. The camp had a mission hall which doubled as a school, and modern facilities such as piped water, and even electricity.

As has been well documented, the outbreak of the First World War resulted in thousands of men flocking to join the army. Tapping into this popular movement were the war-time raised Kitchener battalions raised by individuals (for example, Mrs Emma Cunliffe-Owen raised two ‘Sportsmen’s’ battalions) and diverse organizations such as the West Riding Coal Owners Association and the British Empire League. Many of these battalions were raised by the Mayors of numerous Cities up and down the country, one of whom was the Lord Mayor of Leeds.

At 9am on 3 September 1914 the first recruits for the ‘Leeds City Battalion’ were recruited in the town hall. Clearly aimed at ‘professionals’, the advertising for the battalion stated ‘…only non-manual workers should apply’. Despite (or perhaps because of) this ‘exclusivity’, five hundred men had enlisted by the end of the day. By the end of the second day, 800 men had signed up.

Possibly taken aback at the rapid recruitment of the battalion, the Leeds City Council soon had to turn its attention on where to house the men (a total of 1,200 men were recruited in the initial surge).

Although no doubt many men would have preferred a training camp near their homes, the distraction of being in camp and undertaking serious training in the glare of friends and families may have exercised the minds of those on the recruiting committee. Their solution was no doubt influenced by someone remembering the navvy camp at Breary Banks was, if not the right size, at least constructed and available.

On 14 September the General Purposes Committee of Leeds City Council met and passed the following resolutions:

- That such of the Corporation lands in the Ure Valley (Colsterdale) as may be required for training purposes be set aside for the use of the War Office in connection with the Leeds City Battalion

- That such of the huts and dwellings as can be reasonably spared at the Breary Banks Village be set aside for their use, having regard to the requirements for the construction of the Leighton Reservoir

- That the Waterworks Committee be instructed to proceed at once with the construction either by contract or by direct labour of all the necessary buildings and works in accordance with the requirements of the War Office.

Whilst some of the men could be housed in the huts previously used by the navvys (work on the reservoir was to be suspended) many men would have to be accommodated in tents. An appeal for tents and blankets was made.

Just a few days later, on 23 September, 105 men left by a North Easter Railway train from Leeds City Station to Masham via Harrogate.

Above: A blue plaque adorns the side of the good shed commemorating the Leeds Pals, who arrived by train at Masham station in September 1914 and marched up to Colsterdale to begin their training for war.

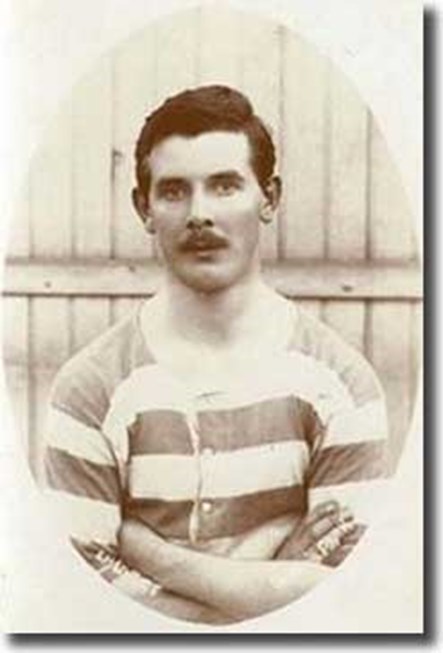

One of the men leading this group was a former Leeds City AFC and England international footballer, Evelyn Lintott.

Above: Evelyn Lintott.

From Masham they transferred to the light railway to Breary Banks.

The advance party was tasked with erecting tents, in order to accommodate the recruits. Only one of the four companies of Leeds Pals would be afforded the luxury of the navvies huts.

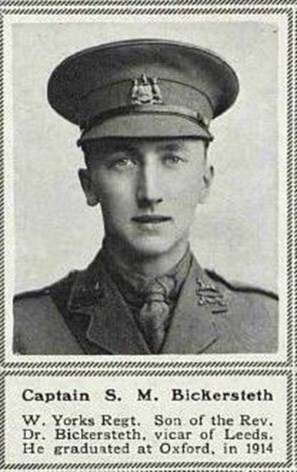

Two days later, on 25 September the rest of the men followed. Crowds estimated at 20,000 saw the men off from Leeds. Virtually no uniforms had been issued; Morris Bickersteth (the son of the Vicar of Leeds Parish Church) was one of the few to have managed to acquire a uniform.

Arriving at Masham station, the recruits loaded their baggage onto the light railway, formed fours and marched the six miles to Breary Banks.

The unit’s training is well documented in Laurie Milner’s book.[1] Anecdotes of the men (many of whom left to be commissioned in other units) abound – the commanding officer was unpopular (at least with Morris Bickersteth).

The battalion – which had undergone a fundamental change of character due to the loss of its initial volunteers and replacement with other recruits eventually left in September 1915 for Fovant in Wiltshire.

Some men stayed behind – these were men who were in E Company, and were amalgamated with the reserve company of the Leeds Bantams (17th West Yorks). This formed the nucleus of the 19th Reserve Battalion.

In due course, the battalion – now the 15th West Yorks – were sent abroad, not to France but to Egypt. There they were ordered to guard the Suez Canal. It was whilst in Egypt that the first death on active service occurred, when the battalion lost Private Edward Wintle to an accident (he was killed when a comrade accidentally discharged a rifle when cleaning it).

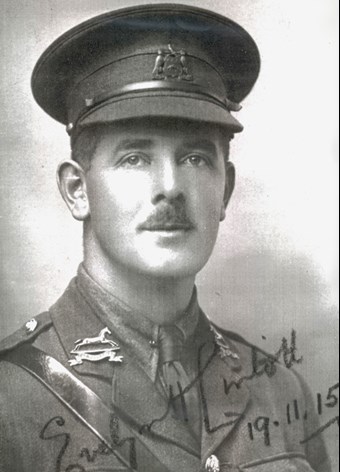

As is well known, the battalion lost very heavily in the attack on 1 July 1916. Among those killed were Lt Morris Bickersteth and Lt Evelyn Lintott.

Above: Lt Evelyn Lintott and Lt Morris Bickersteth

Bickersteth – unlike Lintott – has a known grave and is one of nine identified burials at Queens Cemetery, which lies in No Mans Land.[2]

The site at Breary Banks was not abandoned. It was used to train more troops, and also later in the war house German Prisoners.

On 28 September 1935 the memorial cairn was unveiled at Colsterdale. It was the focus of the Leeds Pals Association’s annual pilgrimage until declining meant the association 'faded away'. The memorial was obviously very significant to many of the old soldiers - it is believed over 20 had their ashes scattered here.

[1] Leeds Pals, Laurie Milner (Pen & Sword)

[2] Identified burials from the opening day of the Battle of the Somme are at Serre Road Number 1 (42); Serre Road Number 2 (8) and Serre Road Number 3 (13). A further 136 officers and men are named on the Thiepval Memorial. Other cemeteries with the dead from this attack by the Leeds Pals are Euston Road (9); Mesnil Communal (2); Sailly – au Bois (1) and surprisingly two some distance away: Delville Wood (1) and Thistle Dump (1)