Tommy Capper's 'Immortals' : How effective was the 7th Division at the 1st Battle of Ypres?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- MA Dissertations

- Tommy Capper's 'Immortals' : How effective was the 7th Division at the 1st Battle of Ypres?

University of Birmingham, , 4th August 2014

'Tommy Capper's Immortals' : How effective was the 7th Division at the 1st Battle of Ypres?”

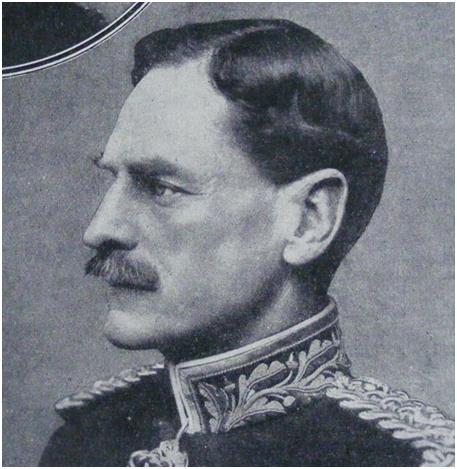

Major-General Thompson Capper, C.B., D.S.O.

The Immortal 7th Division….

For Dad

1921-2014

'Tommy Capper's Immortals'

How effective was the 7th Division at the 1st Battle of Ypres?”

INTRODUCTION

The 'Immortal' 7th Division and its historical context

“There was now the prospect that, in order to fulfil our treaty obligations, it might become necessary to land a force on the continent of Europe for the purpose of protecting the integrity of Belgium”.1

The desperate fighting of Mons, Le Cateau, the Retreat, the Marne and the Aisne had stretched to the limits the original small force that constituted the British Expeditionary Force of August 1914.2 With the departure of the 6th Division to France on 8th September 1914 further reinforcements were needed for the Continent. However, there remained only a tiny contingent of Regular troops on the Home Establishment, with the Territorials still in training. Against this background, a “desperate state of affairs”3, was the 7th Division created, partly from the Regulars left in Britain, but mostly from “the one resource on which the Empire could fall back – the Regular troops stationed overseas, the Colonial garrisons, and the Army in India”.4

7th Division would be led by the remarkable Major-General Thompson 'Tommy' Capper, whose character and 'moral qualities'5 would come to personify the 7th Division at 1st Ypres.

The political and strategic forces at play would put the 7th Division on the Belgium coast in early October 1914, under the ultimate command of Sir John French. French was in many ways “unsuited by experience, knowledge and temperament to command the BEF”6 and “rarely gave the impression he was on top of matters”7, and his command decisions would impact on the fate of the 7th Division8. Initially ordered on Antwerp9 via Ghent to support the Belgium Army10, the 7th Division would withdraw west to Ypres where it would stand and fight. By 31st October 1914, the 1st Battle of Ypres had reached a climax of intensity and 7th Division had been “battered almost out of existence”.11

This dissertation12 will seek to analyse the effectiveness of the 7th Division at the 1st Battle of Ypres by considering the period 27th August 1914, when it was created, to 7th November 1914, the date of its substantive withdrawal from the frontline at Ypres.13

Chapter 1 will discuss the concept of effectiveness in a military context and suggest some parameters by which the effectiveness of 7th Division might be fairly measured.

Chapter 2 will examine the circumstances of the creation and composition of the division, including its preparation and training, and the arduous geographical journey that it took to Ypres. It will also look at the operational leadership decisions that led to the precise deployment of the division east of Ypres and consider the importance of accurate intelligence about the enemy, analysing the extent to which all of these factors improved or detracted from the effectiveness of the division even before the main battle commenced.

Chapter 3 will focus on 7th Division`s involvement in the actual battle, examining the terrain over which 1st Ypres was fought and discussing tactical leadership of the division and the key opposing forces of infantry and artillery. In doing so, we will seek to analyse the division`s effectiveness as a fighting force, taking into account the German forces that opposed it.

Finally, in the Conclusion we will seek to draw together the evidence of the various primary and secondary sources to form some judgements about the effectiveness of 7th Division at 1st Ypres.

CHAPTER 1

Effectiveness in a military context

The starting point is how we define what constitutes the measure of “effective” or “effectiveness” for an analysis of 7th Division at 1st Ypres. There are many books and theories that relate to military effectiveness, but a leading analysis is Military Effectiveness by Millett and Murray and, in particular, the Introduction to Volume 1.14 Their thesis is that military activities have “vertical and horizontal dimensions.”15 The vertical involves “the preparation for and conduct of war at the political, strategic, operational and tactical levels”16 and they contend that the horizontal dimension then forms a matrix with the vertical by consisting of the “numerous, simultaneous, and interdependent tasks that military organisations must execute at each hierarchical level with differing levels of intensity to perform with proficiency. These tasks include manpower procurement, planning, training, logistics, intelligence and tactical adaptation as well as combat”17. In turn, military effectiveness itself involves the conversion of “resources into fighting power...and thus incorporates some notion of efficiency”18, and they refine this further to suggest that one aspect of this efficiency – combat power – is the “ability to destroy the enemy while limiting the damage he can inflict in return”19. “Resources” are the myriad assets that a military organisation can possess, ranging from the non-tangible (such as morale, leadership, learning and politics) to the most tangible (population, industry, technical prowess).

Finally, Millett and Murray acknowledge that within their suggested vertical dimension, there is overlap between the different levels (political, strategic, operational and tactical) and that “one must assess military effectiveness separately at each level of activity…it is doubtful whether any military organisation is completely effective at all four levels simultaneously”.20

They therefore propose a wide-ranging number of factors, mostly subjective in nature, that must be considered in a discussion of the effectiveness of any military organisation, and suggest that such analysis can then lead to valid comparisons and explanations of “relative effectiveness”21 between different military organisations, be they armies or platoons.

An interesting adjunct to the methodology suggested by Millett and Murray is the theory that underpins the so-called SHLM Project22, which began with the construction of a template framework intended to assist a historians to analyse the effectiveness of different British divisions. Although the divisional focus is necessarily much more specific than the over-arching Millett and Murray approach (essentially highlighting the division as one organisational level of the “vertical” dimension), the analytical approach of determining certain key factors and then trying to make objective assessments and comparisons is similar. These factors include planning and preparation, whether the division was defending or attacking, the frontage of line23 it was responsible for, artillery, casualties and the nature of the enemy forces opposing.24

Millett and Murray`s conceptual framework, which is complementary with the types of factors identified in the SHLM Project, therefore provides us with the basis of an analytical methodology. It enables us to approach an evaluation of military effectiveness and, more specifically, the notion of “relative effectiveness” (albeit requiring subjective judgements in a number of respects), which will assist in our analysis of 7th Division. Integral factors in this will be the variable and complex vertical and horizontal dimensions referred to above but also the relationship between victory (however context defines) and military effectiveness. A wargamer can win the game but lose the battle – and vice versa – and Millett and Murray make the key point that whilst military effectiveness and victory will often coincide, this will not always be the case (for example, the “Germans functioned more effectively at the operational level with limited resources”25 than did the Russians 1941-45 on the Eastern Front but the Russians took Berlin). So an evaluation of the effectiveness of 7th Division must be measured in its historical context – the division was pitched into a situation that was “critical in the extreme”26 because if it failed in its task and Ypres had fallen, the road to the coast, and the key Channel ports, was open.27

CHAPTER 2

7th Division and the long road to Ypres

The Official History asserts that “in every respect the Expeditionary Force of 1914 was incomparably the best trained, best organized and best equipped British Army which ever went forth to war.”28 However, this description describes the “Expeditionary Force consisting of six divisions of all arms and one cavalry division”29, being the original force that first crossed to France. Can these words be extended to apply to 7th Division?

The challenge of leading the 7th Division was given to Major-General Thompson Capper (“a man of great energy, driving power”), 30 whose appointment in overall command of the division was dated 27th August “which may therefore be taken as the official beginning of the existence of the Division”.31

Formation and composition of 7th Division

The process of formation of the division is instructive in setting the scene, with Capper having “barely a month to create a division from units that were strangers and with an improvised staff”32. The brigade and other senior commanders were also of unproven quality (“makeshift staff of largely inexperienced officers”33) who, sadly, were to enjoy “strained relations”34 with Capper within weeks. Unfortunately, in spite of all the praise directed at him35, these difficulties would be both caused and exacerbated by Capper`s “lack of interpersonal skills”36.

The assembly point was Lyndhurst in the New Forest37 and throughout August, those regulars available from the Home Establishment enjoyed a “sort of peace manoeuvre life”38 and marshalled as follows:

- 1st Grenadier Guards - from Warley

- 2nd Scots Guards - from the Tower of London (see Appendix 3)

(these two “particularly formidable…elite infantry units”)39

- 2nd Yorkshire Regiment - from Guernsey

- 2nd Border Regiment - from Pembroke Dock

- “C” Battery RHA – from Canterbury

- “F” Battery RHA – from St. John`s Wood

- XXXVth Brigade RFA (12th, 25th and 58th batteries) – from Woolwich

- 54th Field Co. RE – from Chatham.

They were followed in September by:

- 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers and 2nd Wiltshires – from Gibraltar

- 2nd Royal Warwickshires and 1st Royal Welch Fusiliers – from Malta

- 2nd Gordon Highlanders – from Egypt

- 2nd Queen`s (Royal West Surrey), 2nd Bedfordshires and 1st South Staffordshires – from the Cape

- XXIInd Brigade RFA (104th, 105th and 106th batteries) and 55th Field Co. RE – also from the Cape.

This hurried and diverse composition of the division reflects the first of what Millett and Murray would describe as a vertical factor; whatever the attributes of the troops, they were assembled at haste and from widely differing climates and geographies.40

Compounding this, a further adverse vertical factor was that the division was not made up in the same way as the earlier Regular divisions that had gone to France. The Divisional history notes that the RHA batteries took the place of a third brigade of 18 pounders that should “normally”41 have formed part of the supporting artillery of a British division; similarly, no field howitzers or 60 pounder guns were available so instead it was given two Heavy Batteries of “the none too reliable 4.7 inch guns, the “cow-gun” (“notoriously unreliable”)42 of the South African War, a thoroughly inadequate substitute”43. Furthermore, “no Regular cavalry being available”,44 “a whole Yeomanry regiment”45 in the form of the Northumberland Hussars was provided, a cyclist company was made up from infantry units and the “Divisional Ammunition Column, the Heavy Batteries and the Signal Company were also improvised, and the three Field Ambulances and the Divisional Train had to be specially brought together”46. It was hard to obtain all the “transport, horses, and other items”47 required. So whilst the first divisions that had gone over to France were at best “prepared enough for the limited war they [the Government] expected”48, the 7th Division was at an even greater disadvantage. This was not an ideal start.

The situation with the infantry (which were grouped into the 20th, 21st and 22nd Brigades under Brigadier-Generals Ruggles-Brise, Watts and Lawford respectively) (see Appendix 1 for detailed Order of Battle) was mixed: those units returning from overseas were on a “higher establishment”49 than home units which meant that they comprised men who had “completed their recruit training and were over 19 years of age”50, “averaging 5 years` service, from healthy stations.”51 They were brought up to establishment by the judicious drafting in of Reservists (typically only 100 to 130 per battalion)52. However, the four battalions from the Home Establishment contained a “high percentage”53 of Reservists,54 men who needed “some time to get back to the habits and conditions of army life and to revive their knowledge”.55 The Divisional history notes that these Reservists had been amongst the first to gather at Lyndhurst in early August and cheerily suggests that they had “ample time to shake down into their places”,56 but the first half of October would soon put this to the test.

The situation with the infantry was mirrored with the artillery: “T” Battery RHA came back from Egypt to form part of XIVth Brigade RHA and as “batteries stationed abroad were kept at a higher strength than batteries at home”57 it therefore needed only to draw drivers for its wagon from the reservists. The home batteries however needed more men.

The highest proportion of reservists was required in the supporting elements of the division – the 55th Field Co. RE needed a high percentage of Reservists to get back to establishment levels58, and the Divisional Ammunition Column contained “a high percentage of Reservists”.59

Most battalions also required some additional officers, who again were brought in from the Reservists and various changes in the senior divisional staff “did not tend to assist”60 mobilisation.

The Divisional history notes that “though some of the units were not strangers to each other…the Division as a whole had to start at the beginning to gain that coherence and corporate spirit which the first six Divisions had acquired from working together in peace”61 (and keeping the two Gibraltar battalions together in the 21st Brigade and the two Malta battalions in the 22nd was no doubt intended to assist in this cohesion).

Millett and Murray`s framework therefore helps to reinforce a view that the assembly of the division had positive and negative factors – a seemingly impressive commander, strong in regular infantry, but (relative to the original divisions sent to France) with a senior leadership team assembled in haste, and deficiencies in its cavalry, artillery and support arms. In the understandable haste of 1914, the example of 7th Division indicates that Kitchener`s broader fears for the readiness of the army were indeed being realised.62

Preparation and training of 7th Division

At the time of this appointment, Capper was the Inspector of Infantry and highly regarded throughout the army, his success with 13th Brigade in Dublin63 still fresh in mind. He had “much experience as a trainer of troops”64 and his reputation had been recognised with his appointment as Inspector of Infantry in April 2014.

Capper must have realised time was against his new force so “With characteristic energy and zeal General Capper started Brigade and even Divisional training directly units could be got together. There were repeated field days and constant route-marches; indeed before orders to move arrived the Division had, as one officer put it, “marched close to three hundred miles about the New Forest by way of hardening the men who had come off foreign Service”.65

This additional training was probably necessary66 because although the men were “generally fitter than the men of the first six divisions, the 7th Division troops would not have been at peak physical fitness. Garrison duty in hot and enervating climates such as Malta and Egypt was not conducive to energetic training…and any lack of fitness would have been exacerbated by a sea passage in crowded troopships”.67

Nevertheless, “even in comparison to the other divisions of the BEF in 1914, accounts of contemporary observers suggest a widespread perception of Capper`s division as a superior formation”, much due to the high percentage of regular troops.

However, whilst the Divisional history notes that “these exercises68 did give commanders and units some chance of getting to know each other”,69 “nevertheless, the division was still rather a “scratch” team when it embarked for Flanders”70. Certainly, by the time 7th Division and 3rd Cavalry Division (together, IV Corps under Rawlinson) embarked for Belgium they had “little or no experience operating in large formations”71 and no amount of Capper`s energies could change that. Moreover, even though Capper drove his new division hard, Rawlinson was to complain they were “not yet fit…not good marchers”,72 many having just returned from softer colonial duties.

Overall therefore, mobilisation of the division would be described as a “difficult process”,73 with Capper`s charismatic personality and regimental reputations perhaps distracting attention from more tangible factors that would come to play a part in the hard weeks ahead.

Millett and Murray`s framework therefore suggests that in this “horizontal dimension” of preparation and training, again there were positive and negative factors in play – the positive influence of Capper offset by the severe limitations of time.

The march to Ypres74

Once the embarkation order was received on 4th October, the division moved quickly75 and between dawn on 6th October and dawn on 7th October the division was landed in Belgium76 via Zeebrugge, from a variety of vessels of differing comfort.77 It was largely concentrated around Bruges by 5pm on the evening of 7th October78 and in the best traditions of the British army, the grumbling had already begun (“officers in houses…latrine accommodation scanty”).79

At this point, the orders80 for 7th Division were to relieve pressure on the Belgium army81 and the city of Antwerp.82 On 8th October, “the whole Division was ordered to march to Ostend, to cover the landing of the Cavalry Division – a hot and tiring journey it was of fifteen miles, over the usual paving stones.”83 The War Diary of the South Staffords complains that “many men…got and suffered from sore feet from this trying march, which they did not get rid of until they got to Ypres”.84 On the 9th, trains took much of the division east to Ghent,85 to cover the withdrawal of the Belgians, and during the evening rain fell unceasingly, with fires banned for the Gordon Highlanders due to the expected proximity of the enemy, meaning “the troops in bivouac were unable to cook.”86 However, by the 11th, Antwerp had fallen and the division was now to concentrate around Ypres, and this meant “long marches and few intervals of rest”.87 For the Grenadier Guards, the march to Thielt on the 12th involved “being up all night and marching all day”,88 on the 13th, the march to Roulers89 was punctuated with “irritating and fatiguing halts”90 and the final march into Ypres on the 14th was in heavy rain on roads in a “terrible state”.91 The Bedfords complained of a “tedious march [with] checks caused by Div. Train”.92 The Scots Guards had it no easier, as “the cold was trying, as was the unaccustomed marching on cobbled roads, which…are a terrible affliction to the feet of the infantry.”93 Interestingly, the Gordon Highlanders` history admits that by the time the division reached Ypres on 14th October “first class though the infantry of the 7th Division was, the men were not in the hardest condition. They had had long marches on the notorious Belgium pave which had swollen their feet, while wet had shrunk their shoes, and very little in sleep”.94 The 15th , for example, saw the Queen`s “fall out in a field most of the day, the men getting a badly needed rest”.95

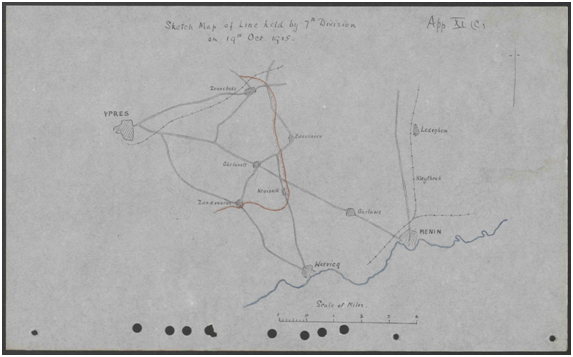

Even by 12th October, the diarist for the South Staffords wrote that “hitherto the march had appeared something aimless and in the nature of a flight”.96 The Official History summarises that “from the time when the 7th Division left Ghent, on the night of 12th October…it had had practically no rest. The advance to Ghent (see Appendix 4), and the retreat from Ghent to Ypres, a forced march of more than forty miles in forty hours, proved very exhausting to a new formation,97 and the men – many of whom were only fresh off a sea voyage from South Africa and elsewhere – were already tired when, on the 16th October, they were digging themselves in on the Ypres front.”98

The Millett and Murray`s framework would clearly suggest that, insofar as the assembly and training of the division was intended to represent the moulding of a military resource into “fighting power”,99 7th Division`s intense manoeuvring before it took up positions around Ypres inevitably degraded the efficiency of the division because the troops were already exhausted before they were called upon to fight – certainly not the best preparation for the “horrors impending”.100

Intelligence, and leadership of 7th Division from Army and Corps levels

Good intelligence, which at an operational or tactical level is often secured by reconnaissance, is a critical aspect of warfare and it informs the decisions of commanders. An understanding of the enemy`s position, size and capabilities, combined with an understanding of what is happening in the fighting line, is critical to higher echelon commanders seeking to control a battle by the issuance of evidence-based orders. From the outset, 7th Division was to pay a price for defective intelligence at strategic and operational levels. The prevailing view, shared by Churchill and Kitchener, that the Germans lacked the strength to mount a full-scale attack on Antwerp was clearly proved incorrect but was the basis for the initial deployment of 7th Division.101

Even before 7th Division retreated from Ghent, the warnings were there: 102 “aeroplane reconnaissance pointed to considerable numbers of the enemy E. and S.E. of Ghent”.103 Once 7th Division was in position around Ypres, at a more operational level the division was tasked to undertake offensive operations which better intelligence or reconnaissance would have suggested were unwise, or even reckless. “Ominous indications”104 of increasing German strength were dismissed by G.H.Q. and 7th Division`s War Diary naively noted that “the superior information available at General Headquarters over-rode the possibly exaggerated local news”.105 From 14th October, a succession of orders from Sir John French based upon optimistic estimates of German forces and British capability (including the ambiguous “move on” Menin Operation Order No.38 of 17th October), could have imperilled the division to an even greater extent than actually happened. In Haig`s diaries, he notes a conversation with Sir John on 16th October where French is reported as being “quite satisfied with the general situation and said that the Enemy was falling back and that we “would soon be in a position to round them up””.106 By the 19th October he reports (with the battle now commenced) that Sir John “estimated the Enemy`s strength on the front Ostend to Menin at about one corps, not more”,107 while available information108 clearly suggested the opposition of not less than five corps and other supporting divisions drawn from the German 4th and 6th Armies facing the British and French forces defending Ypres.109 Capper`s enquiries to G.H.Q. on the 18th (based on his concerns about enemy strength on his flank) had the result that “various important officers turned up at Divisional Headquarters who pooh-poohed the idea that the concentrations…amounted to anything significant”.110 Nevertheless, 7th Division was ordered forwards111 and it was only the “sound judgement”112 of Rawlinson, perhaps based on the good information113 he did have about German numbers,114 that caused the advance to be broken off.115 The poor communication between G.H.Q. and IV Corps and Rawlinson`s consequent use of initiative was to lead to a serious worsening of the “already shaky relationship” between French and Rawlinson. 116 French`s orders to drive forwards were clearly based on a wholly inaccurate understanding of the forces that confronted the British around Ypres.117 Indeed, towards the climax of the battle, Haig also ignored French`s orders of 29th October for a further advance because “just how difficult the situation was on the ground had passed Sir John French by”.118

The consequences for an already fatigued 7th Division of this poor use of intelligence were severe. Casualties were taken in offensive manoeuvres which should not have been undertaken, leading to retreats back to unprepared positions. This in turn connects to the debate (see below) about the adequacy of the trenches it dug. Had 7th Division been ordered to dig in properly across the Menin Road early in the battle when the troops were not in constant contact with the Germans, it is arguable that its entrenchments might have been both sufficiently secure so as to have avoided the later criticisms made of them and strong enough to reduce the severe casualties that would be taken from the German artillery.119 In a number of instances, it was to be Rawlinson120 and later, Haig, who would mitigate unrealistic orders from G.H.Q., and without their intervention, perhaps 7th Division would have suffered even more grievously than it did.

All this said, it must also be noted that the Germans suffered from similar deficiencies in their intelligence, never quite appreciating the precariousness of the British position,121 or the thinness of the defensive line.122

The discussion above links the military intelligence available to G.H.Q. and IV Corps to the command decisions that determined where 7th Division would stand and fight. In so doing, it brings together both horizontal and vertical factors of the Millett and Murray approach in the matrix of the analysis. What can be concluded is that 7th Division was badly served, and that after the trials of getting to Ypres, bad use of information and conflict at higher levels of leadership exposed the division to further stresses before the main fighting began; Rawlinson may have made some good judgements but 7th Division did not have the chance to prepare for the defensive battle it would have to fight on the best ground it could have chosen. This further impaired its effectiveness.

This Chapter 2 has therefore examined some of the significant challenges faced by 7th Division in getting to Ypres and before the main battle began. Once it reached Ypres, needing rest, it was given objectives by G.H.Q. based on “false information”123 that were never capable of being achieved (such as the capture of Menin) that cost it unnecessary casualties in futile offensive actions. These actions, in turn, deprived the division of the time and opportunity to prepare its defences to protect Ypres and the roads to the Channel ports. Fatigue, compounded by poor use of available intelligence and resultant bad leadership decisions can therefore can be regarded as further factors which eroded the effectiveness of the 7th Division`s capabilities,124 and this was all before the real fighting had started.

CHAPTER 3

7th Division and the offensive spirit on sacred ground - the 1st Battle of Ypres

This third chapter has a more tactical focus, and will examine the terrain over which the battle was fought, the leadership of the 7th Division, and the opposing forces involved.

Terrain

It is all too easy to think of the ground over which 1st Ypres was fought in terms of the photographs historians know from the later Passchendaele battles of 1917. Peter Barton, perhaps the leading topographical expert on the battlefields of the Western Front, makes the point that there are relatively few 1914 photographs of the area and the modern reader`s view is therefore coloured by the many images of the blasted wasteland of 1917. In 1914, the area around Ypres was still a bucolic and verdant farmland “full of smoky little villages”.125 Jack Sheldon notes there were “hundreds of kilometres of hedges which…surrounded small fields”.126 This echoes the Official History which notes the fields were “small, often divided by hedgerows with many trees in them…a green, fertile, but blind country…bad for infantry, almost impossible for mounted action and very difficult for artillery”.127 From the earliest engagement with the enemy, the 7th Division had “a long and thinly held front, and in country as yet little damaged by war, so that buildings, hedges, and woods provided excellent cover, [so] it was impossible to keep every line of approach under effective fire”.128 For example, 20th Brigade War Diary notes the “enemy massing in the dead ground near America”129 and the Welsh had the same problems to their front.130 However, the dense hedges and woods, hard to imagine in modern Belgium, led to a “canalisation of offensive movement”131 when the Germans attacked. The terrain therefore mostly worked to the advantage of the British defenders, artful at letting “the attackers get to close range then, from hedges, houses and trees, opened up withering rifle and machine gun fire from point blank range”.132 This, in Jack Sheldon`s words, is “the way the infantry battle was fought”.133 “Clear fields of fire were few and far between, and, therefore, all the more valuable”.134

Similar considerations would affect the artillery as well. “The battlefield was not ideal for artillery. Villages and copses were largely intact”135 and the low ground was often shrouded with “ground fog or morning mist”,136 leading both sides to use church steeples, observation aircraft (“as best they could in the mediocre weather”)137 and, in the case of the Germans, an observation balloon.138 Artillery would cause heavy casualties on both sides, but the terrain dictated that 1st Ypres would be primarily an infantry battle.

The terrain would also help provide the luck that 7th Division would require. Later in the war, the tree cover around Ypres would have been obliterated but in 1914 the lack of good sight lines helped to save the British as it disguised the “slenderness of the reinforcement”139 that was all that stood between the 7th Division`s trenches and Ypres. More than one of the 7th Division regimental histories describes the frustrated fury of the Germans when they realised this fact.140

Millet and Murray list “tactical adaptation”141 as one of the many tasks comprising the horizontal dimension of warfare. Within their analysis, one can conclude that on balance the constraint of the terrain was a factor that played to the advantage of the highly trained marksmen of the British regular army as they met the German onslaught. The Germans might use the ground and cover to mass close, but the British infantry`s training meant they could deploy heavy fire at critical points in the line against these dense German targets. Their “combat power”142 was therefore enhanced by the effects of terrain and, with that, their overall effectiveness.

Capper and leadership within the 7th Division

The dominant figure of the 7th Division was Thompson Capper, “a legend in his lifetime”143 and whose reputation and that of the 7th Division at 1st Ypres are inextricably linked. On hearing of his death in 1915 (see Appendix 6), Reginald Tompson wrote of Capper that “the ambition of his life was to be killed in action, which is some consolation. A braver man & a better general never walked”.144 Capper was considered to have “impressive intellect”145 and was part of the “galaxy of future stars”146 who were contemporaries of Haig at Staff College.

Capper and his contemporaries had gained their fighting experience in the smaller wars of the late Victorian era (including the Boer War) and they were unprepared for the challenges of commanding the larger forces of 1914,147 although his surviving papers perhaps suggest that Capper could anticipate the “national struggle for existence”148 that would follow. It is clear from a number of accounts of the early battles of the First World War that the inability to “see” what was happening on the larger battlefields of this new type of war was a challenge149 representing a critical impediment to command. Indeed:

“In the absence of reliable communications between the front line and the headquarters in the rear, many senior officers instinctively tried to get nearer to the front. But rather than producing circumstances whereby such commanders could control their units, it brought them into closer touch with the enemy, often with devastating results.”150

These words could have been written with Capper in mind. Capper “personified the British Army`s offensive spirit”151 and there are numerous references to his presence in the front line throughout the 7th Division`s engagement at 1st Ypres.152 Undoubtedly he did embody the “offensive spirit”153 that he advocated so strongly (and in fact he was to die close to the front line at Loos in 1915 when “it is clear he should have been much further back”),154 and it is this that has in part made him a controversial figure. Whilst there can be no doubt about Capper`s physical bravery and belief in self-sacrifice,155 by 1914, raw courage was not necessarily an indicator of suitability for highest command. However, John Terraine has described him as a “very fine divisional commander”156 and perhaps 1st Ypres can be distinguished on the basis that the nature of the grim defensive fighting and the lack of reserves justified Capper`s presence in the line. He certainly seems to have had an impact in this regard – “no one but Capper himself could, night after night, by sheer force of his personality have reconstituted from the shattered fragments of his battalions a fighting line that could last through tomorrow”.157 The Official History`s description of Capper “personally inspecting the front line during the night”158 on 27th October is only one of many references to Capper`s valour and energy, and the ability of the division to “maintain a semblance of cohesion despite such heavy casualties was in no small part due to the personal leadership of its commander”.159 Capper`s actions throughout the battle160 seem to echo back to his words of 1908 and his desperate desire to retain “bold initiative preserved under all conditions [and an] uncompromising offensive”.161

Against this, Capper brought to the battlefield (or perhaps just permitted?) some tactical innovations that may not have been wholly successful, such as the use of forward slope entrenchments (see discussion below). Moreover, Capper had a command responsibility to bring together the “improvised staff”162 he inherited from Rawlinson but he “seemed to lack the steady temperament necessary to win the confidence of his subordinates”.163 Capper had “poor relations”164 with his staff and did not have “effective professional relationships with his brigade commanders”165 and a consequence of this was “discord among officers within 7 Division”166 which was to impact on divisional cohesion during the fighting and perhaps the “poor communications”167 within the command structure in the critical fighting from 26th October and after.168

These contemporary concerns expressed about Capper (and there is a suggestion that his personality became more extreme and eccentric as he got older)169 suggest that his fitness for highest command would have been questioned had he lived beyond 1915. However, in the extreme circumstances of 1st Ypres, it is arguable that 7th Division had the commander it needed for to sustain in it the sacrifice required to hold the line. By his actions one saw his beliefs: “Capper, true to his belief in the offensive spirit, personally led counter-attacks against overwhelming attacks, holding together a fragmented British defence”.170 Paradoxically, it was the offensive spirit used in desperate defence that was his greatest achievement and helped to both draw the power from the German advance and suggest that the British were a larger force than they actually were. The Grenadier Guards diary asserts:

“There can be no doubt that the German were completely deceived as to our strength, and that what misled them was the…almost reckless audacity with which the Grenadiers and Gordons attacked…These continual counter-attacks gave the impression that there must be large reserves in rear”.171

This was indeed the “offensive spirit” and, consistent with this,172 Capper was “constantly up in the firing line to exhort and encourage the weary men, to instil into them something of his own unflinching determination to endure to the end”.173 However, whatever Capper`s efforts, sight must not be lost also of the fact that so much of the leadership in the division derived from battalion and company commanders who played a fundamental role in the fighting of 1914 generally;174 in particular, once Rawlinson was stepped down by French, it was the “battalions of 7th Division”175 that held the line, underpinned by the “personal bravery and leadership of junior officers”.176

In terms of the Millet and Murray analysis, Capper must be judged by his effect on “combat power”. In this respect, set against his prime task of holding the Germans away from Ypres, the evidence suggests that whatever his failings, he was a positive factor in the overall effectiveness of 7th Division. He did not have as much time as he would have liked to train the division before it embarked but once in the line “There can be little doubt that the steadfastness of the 7th Division under Capper`s inspirational leadership was absolutely critical to the avoidance of defeat and to success at Ypres”.177

The opposing forces - the British and German infantry

At its heart, 1st Ypres was a confused and desperate infantry battle,178 and a hellish experience179 for the infantry of all sides involved180 (and in this should be included the French and Belgians, fighting north and south of the British, but with the French increasingly inter-mingled with the British as the battle developed). 181

How then should we evaluate the infantry in assessing the effectiveness of 7th Division? There are three particular themes in the literature that are critical in any analysis of 7th Division`s performance.

The first of these themes is how effective 7th Division`s infantry was at stopping the onslaught of heavy German attacks. As the battle began, “the front of the Division was approximately 8 miles long”182 and this “attenuation of Rawlinson’s relatively weak force would prove dangerous”.183 As the battle developed, the key task of 7th Division became to defend the eastern approaches to Ypres against successive German attacks. Spencer Jones has written how “the army of 1914 utilized flexible tactics that emphasized dispersion, intelligent use of the ground and skilful marksmanship”184 and the fighting that developed around Ypres “should be seen as the tipping-point from mobile warfare to trench warfare, as numbers became even less important and firepower began to dominate the struggle.”185 The importance of field entrenchment is discussed below but the “enduring reputation for skill”186 enjoyed by the Old Contemptibles is inextricably bound up with its “maximization of infantry fire power”.187 “What the Old Contemptibles did have to offer was a uniquely high volume of musketry, in their “mad minute” of concentrated fire at relatively close range.”188 In this critical regard, did 7th Division`s infantry live up to the reputation of those divisions that had retreated from Mons where these “outnumbered British professionals…proved themselves the superior in nearly every respect of their German opponents…[with] their accurate and rapid fire mistaken for machine guns”?189 The evidence strongly suggests that this must be answered in the affirmative. Unlike some of the earlier encounter battles, 1st Ypres was a sustained struggle lasting weeks across the same ground. Jack Sheldon explains therefore that the “watchwords for the defending infantry were fire discipline and conservation of ammunition; both of which were best achieved by allowing the attackers to get close to defended localities and then pouring lacerating fire into them at short range for as brief a time as possible190 - this was the nature of the “mad minute”, and he quotes an excellent example of this as the Germans entered Beselare on 20th October: “At that moment shots rang out from all sides, the shock blotting out all the sight and sound…they had suddenly brought down a hellish rate of fire against us”.191 Hard lessons in South Africa had taught the British the importance on the defence of “vanishing under cover, and developing a great volume of fire-power from concealed positions”.192

And there is no doubt that as the battle developed from the German assault on 20th October to the 31st October, the British (who “felt anything but pleased with the Germans”)193 got better,194 in what was a brutal struggle.195 Peter Hart has commented that “as the power of the assaults built up, there is no question that, for the most part, the British soldiers were making a better fist of the battle.196 As they gained the experience their pre-war training had not given them (although that training had given each man “confidence in his rifle”)197 their tactical dispositions slowly gained in subtlety (“accurate fire from a series of well-placed mutually supporting fire positions”).198 There were still mistakes and instances of panic but co-operation improved between neighbouring units”.199 However, it can perhaps be better contended that “the experience gained in South Africa led directly to the creation of the highly trained BEF infantryman of 1914”200 and it was this and the improved training of the 1902-14 period that the men of 7th Division could fall back upon (with the Germans concluding that “such had been the British resistance that they believed they faced strongly entrenched positions”).201 This was certainly the view of John Terraine:

“In the end, however, it is the infantry soldier, and particularly that superbly trained infantry man of the BEF, with his “mad minute” rifle fire which persuaded the Germans that they faced lines of machine-guns, who emerges as the hero of this battle. Thanks to him and his allied comrades….all the German attacks were held.”202

The infantry of 7th Division therefore represented a deadly opponent, particularly on the defensive, because from static firing positions meeting German assaults, its generally high level of training (personified by its musketry) and strong morale, meant it could inflict high levels of casualties on the attacking Germans.

The second theme in relation to the 7th Division infantry is its moral and physical resilience in holding the line; in short, its ability to endure. The infantry was at the centre of 7th Division`s fighting power and, whilst the division itself had been assembled in haste, like the rest of the army “its great strength lay in a regimental system that fostered a regimental pride and esprit de corps that was at the very heart of British military tradition”.203 If they did not yet think of themselves as “the 7th”, the individual battalions certainly arrived at Ypres imbued with the traditions of their regiments.204 The warm welcome they enjoyed from the local population on arrival in Belgium, who regarded the British as saviours, could have caused them to underestimate the task ahead (“the people were very good to our men, but would take all their cap and collar badges, a great nuisance afterwards, as it was impossible to tell a man`s unit when he fell out”)205 but there can have been no illusions once the fighting began.

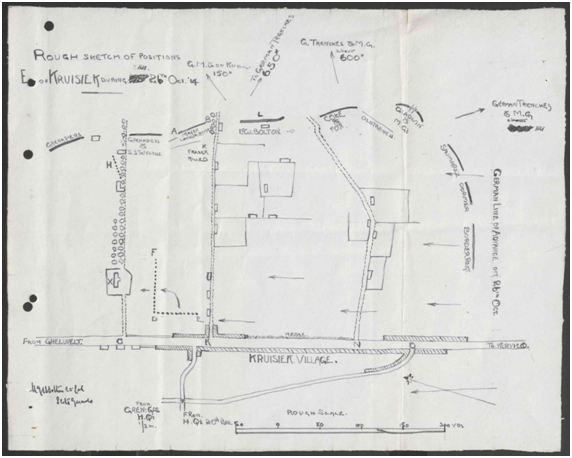

Between October 15th and 18th Capper pushed his vanguard to a line running NE/SW from Terhand to ”America” with sniping and skirmishing, but once forced to press the attack further towards Menin “it was clear that the enemy were in much greater force than G.H.Q. had anticipated”.206 The 7th Division`s history tries to make a virtue207 out of the shocking failure of G.H.Q. to use the reasonably good intelligence it had208 regarding actual German numbers209 but now, from 20th October, began the German attacks. Facing them, across both sides of the central pivot of the Menin Road and the Gheluvelt Ridge, and with its right flank distorted by the Kruiseike210 salient,211 was 7th Division. Huge attacks fell on the division on the 20th and 21st October and almost inevitably Lawford`s brigade (the 22nd) was forced back in “considerable disarray”.212

Nevertheless, by 23rd October, the division was still holding a line eight miles long (it had “not given ground although attacked by three times its numbers and outweighted heavily in artillery”).213 The days of attack and counter-attack were so brutal and confusing that 7th Division`s history has to admit that the fighting of the 24th seemed “to defy all efforts at elucidation”214 and a shortening of the line on the 24th brought only a “small measure of relief”.215 7th Division was taking the brunt of the attack and by the 24th, “the majority of its officers and men had to remain in the positions they had been defending for nearly a week,216 weary, unwashed, unshaven, short of sleep and sometimes of food, but grimly resolute.”217

Further setbacks were to follow. On 25th October, Ruggles-Brice`s 20th Brigade (“in exposed positions under heavy attacks for a full week”)218 also began to give,219 with two companies of the 2/Scots Guards being overwhelmed. By 26th October, 20th Brigade “proved unable to withstand the continued bombardment…[and] had largely disintegrated and its units began retiring in disorder”.220 The 20th Brigade gets the highest level of admiration from Ernest Hamilton (“superb devotion…an example of unflinching heroism…fought till there were no more left to fight”)221 but this is where the reputation of 7th Division develops an element of controversy. 26th October was a self-evidently a hard day for the division and Haig`s diary comments critically that:

“a report from IV Corps reaches me that the 7th Division which is holding line from crossroads southeast of Gheluvelt to Zandvoorde is giving way….several battalions in great disorder passing back through our 1st Brigade….by 4pm the bulk of 7th Division had retired from the salient about Kruisek, most units in disorder….I rode out about 3pm to see what was going on, and was astounded at the terror stricken men coming back. Still there were some units in the division which stuck to their trenches.”222

Haig clearly thought the problem was with their entrenchments: “It was sad to see fine troops like the 7th Division reduced to inefficiency through ignorance of their leaders in having placed them in trenches on the forward slopes223 where Enemy could see and so efficiently shell them”.224

Haig was referring to 20th Brigade but this charge was later levelled at both 22nd and 20th Brigades so it would seem that with respect to its entrenchments, a critical protection given the position it was in, 7th Division was found wanting on more than one occasion. There are numerous accounts of the inadequacy of trenches generally during the fighting, but even though training was given,225 there is no doubt that the appalling conditions of the Salient, in such constant close proximity to the Germans, militated against preparing substantive earthworks.226 This appears to have been compounded for 7th Division by a lack of equipment227 so “there was great difficulty in making good trenches, for, owing to night work and constant retirements, the loss of picks and shovels…had been very great.”228

However, there may be more to it than that because the Official History comments that “both Sir John French and General Rawlinson229 were of the opinion that the heavy losses [of 7th Division] were due in some measure to the nature of the trenches favoured by the divisional commander - the type used by the Japanese at Port Arthur, with overhead cover – and to these trenches being sited on the forward rather than the reverse slope”.230 The General Staff`s Notes on Field Defences, noting that “where possible, trenches should be sited so that they are not under artillery observation”, came too late for the men of 7th Division231 but the implication is that lessons were learnt from 1st Ypres.232 There is therefore both a criticism of the method of entrenchment233 and the clear suggestion that senior command held Capper responsible for this.234 That said, the debate becomes more complex with the suggestion that under the “prevailing command philosophy of umpiring, the location of trenches was the responsibility of the brigadier…duties of the corps and divisional commanders would not have extended beyond the selection of a general line of defence”.235 This would seem to put blame back onto Lawford and Ruggles-Brise (“neither Lawford nor the other brigadiers of 7 Division were apprised of the lessons regarding trench location collected earlier in the campaign”)236 but, given how much time Capper spent in the front lines, is this fair or credible? Given what we know of Capper, it does not seem likely that he would not have expressed his views on such matters,237 and 7th Division did receive explicit orders from IV Corps HQ on 21st October to make trenches “as invisible as possible”.238 More generally, it seems clear that the failure of senior officers to acknowledge the intensity of the German counteroffensive left 20th Brigade “in exposed positions under heavy attacks for a full week”,239 defending the exposed right-angled salient around Kruiseke. Haig`s noted enquiry as to whether they were “merely leaving their trenches on account of shell fire”,240 seems to dismiss summarily a brigade that had been tested beyond reason. However, “even after the 2/Scots Guards were driven out of positions in the evening of 25th October, they counter-attacked in the dark of 26th October, before again being blasted out by artillery”241 so they still had some fight in them242 (“resuming the offensive directly the enemy gives us a chance” as Capper would have put it).243

So Haig`s harsh words should be treated with caution. Haig himself was under extraordinary strain, and a contemporaneous diary entry in the middle of the battle must be considered in context. Most sources credit the extraordinary resilience of 7th Division in holding the line against successive attacks.244 However, it is therefore not surprising that by the end of nine days of “continuous fighting”245 to 26th October “the 7th Division was beginning to show signs of exhaustion”246 with its casualties now amounting to 44 per cent of its officers and 37 per cent of its men”.247 This is clearly evidenced in Montgomery`s terse instructions to 7th Division on 28th October remonstrating about “cases…of faulty-co-operation”248 between units, rules for withdrawals and a reminder that “those who retire imperil the whole army”.249

Compounded by the “manifest collapse”250 of 20th Brigade, and short of food and small arms ammunition, and without proper artillery cover or enough machine guns, G.H.Q. now feared that 7th Division was no longer capable of holding its positions so “units of Haig`s I Corps began taking over Capper`s line, thereby allowing the battered division to reorganize”.251

Finally, by 7th November, most of the remnants of the division – the “mere wreck”252 that was left – were relieved and pulled back out of the line, its horrendous casualties “the inevitable consequence of the task which fell to the share of the Division and was successfully carried out by it”.253

What then can we conclude about the infantry of 7th Division? The Official History acknowledges the huge pressure 7th Division was under: “The frontage held by the division at all stages of the battle254 had been so extensive, that it had hardly ever been possible to maintain a substantial reserve”.255 In this respect it is noteworthy that the SHLM Project particularly identifies the ratio of length of line to manpower as a key factor in any qualitative analysis in the context of British divisions in the First World War.256 When one looks at the circumstances that preceded the battle (Chapter 2 above), the length of time they were in the front line and the strength of the Germans facing them (see below), the initial view must be that they put up a remarkable resistance. In his leading book, Death of an Army, Anthony Farrar-Hockley says of the British army at 1st Ypres that “what marks them is the standard they set as fighting men, holding for weeks a wide sector of attack against an enemy four to seven times their strength”.257

This view of the British is echoed in the German Official Account:

“The fact that neither the enemy`s commanders nor their troops gave way under the strong pressure we put on them, but continued to fight the battle round Ypres, though their situation was most perilous, gives us an opportunity to acknowledge that there were men of real worth opposed to us who did their duty thoroughly”,258

so this is the third factor that we should consider: how did the men of 7th Division rate against the Germans who faced them? In other words, what was their relative effectiveness (in the terms of Millett and Murray)? The opponents of 7th Division were the men259 of the newly created Fourth Army, created by Falkenhayn (under the Command of Duke Albrecht of Wurttemberg) which it was intended would “force the line of the Ijzer in strength”260 and sweep south. However, the redeployment of 80,000 Belgium troops from Antwerp, supported by French marines, provided a brake on this advance, and the subsequent inundation of the coastal area and the support of the French 42nd Division, brought the Fourth Army to the approaches of Ypres. In Jack Sheldon`s view, the four reserve corps that made up the Fourth Army were “inexperienced”261 and “third rate”262 but there does seem to be consensus in the literature that the four reserve corps of the new German Fourth Army were unprepared for what they would face at Ypres.263 There has been a long debate as to the exact composition of these units (“these consisted chiefly of student cadets and old reservists”),264 and German propaganda in the inter-war years has added to the confusion,265 but it is clear that the haste and problems of “improvising so many formations when the metaphorical cupboard was bare”266 meant that “inevitably corners had to be cut”267 to get more troops hastily to the front. These issues would include shortages and deficiencies in all aspects of kit and equipment, and a lack of trained leaders at all levels. The result seems to have been that “all these problems and a lack of time to overcome them, meant that the standard of training and equipment was abysmal”.268

Once these new units, an “imposing body of men and guns”,269 then came up against the professional soldiers of 7th Division at close range, “those volunteers of the Fourth Army, [were] shot down in droves”.270 For example, employing its fearsome rifle power, “a single platoon of Gordon Highlanders counted 240 dead Germans on its own short front”.271 Similarly, the Borders “held their fire until the Germans were almost on top of them, and then opened with tremendous effect, the assailants being mown down in swathes”.272 This grim story was repeated all along the line that 7th Division held.

The Germans manifestly had a huge numerical advantage but “there was also little doubt that the German troops lacked the skills of their predecessors. The concepts of ‘fire and movement’ – going to ground, co-ordinating rifle, machine guns and artillery to win the fire fight, before the final attack and careful consolidation of gains – were often conspicuous by their absence”,273 views supported by German soldiers who fought in these costly encounters.274 “The actions of the German generals are less easy to excuse. They had quantities of artillery and an abundance of shells yet, time and time again…they sent their men in mass attacks against entrenched infantry, only to have them mown down like summer corn by that fast and accurate rifle fire. Their attacks had great weight and cohesion but it is hard to see where much use was made of either ground or of sensible tactics…battering the Allied line with shellfire and flooding it with manpower, and this was not sufficient to cause a breach”.275

Numerous and consistent accounts of the infantry fighting suggest “rushed attacks, often lacking systematic reconnaissance or artillery preparation”276 which were rebuffed by the “superior field craft and defensive tactics” 277of the British regulars who, time after time, repulsed the “formidable rush”.278

This, therefore, was the “enormous gamble” of German High Command but “high morale and determination” would not be enough. The view of one writer is that “There is no doubt that the English and the French troops would have been beaten by trained troops. But these young fellows we have only just trained are too helpless, particularly when the officers have been killed.”279 Jack Sheldon, perhaps the leading modern authority on the German army in the First World War, is damning: “It is hard to find other examples in history when such inadequately prepared and equipped troops have been sent into battle at a critical point…[with] their state of individual and collective training lamentable”.280

All the evidence leads to a clear picture therefore that “the Germans had greater numbers281 but the Allies (especially the remaining British regulars) were of better quality.”282 In terms of the Millett and Murray analysis, it is apparent that in any measure of “relative effectiveness”283 between the British infantry of 7th Division and the German infantry of Fourth Army the conclusion is that in this deadly manifestation of the “vertical dimension” the British were superior because they were better technical soldiers (their cohesion and pre-war training being a key factor), which, combined with their generally good equipment and high morale, meant they were able to hold off a far larger German force over a sustained period of weeks. Tasked with holding the line, they were highly effective in doing so, albeit they ceded some ground and at an enormous cost in casualties.284

The opposing forces - the British and German artillery

Finally, we examine the artillery of both sides. In his recent book, From Boer War to World War – Tactical Reform of the British Army 1902-1914, Spencer Jones notes the challenges that faced the British artillery following the chastening experience of the Boer War, and some of the lessons learned (including the need for “accurate long-range fire, concealment, and close co-operation with infantry”).285 However, he still concludes that the artillery entered the First World War with “a lack of numbers and an absence of uniform doctrine”,286 compensated for to some extent by “highly accurate gunnery and many good tactical ideas within the branch”.287 However, as noted in Chapter 2 above, in addition to a general lack of guns, 7th Division had less than the desired complement of guns with some older inadequate weapons as a make-weight. Compounding this was one critical deficiency in the preparation for war in respect of the artillery that would prove to have serious repercussions, and this was the approach to ammunition supply. Jonathan Bailey has written a scathing account288 of the development (doctrine, tactics and equipment) of the British artillery which meant that it was ill-prepared for the intensity of fighting of 1914. From the Boer War and the Russo-Japanese War “the British learned the wrong lessons, emphasising the need for fire economy rather than increasing the supply of ammunition”.289 This would be an issue for all of the BEF in 1914, but particularly 7th Division in late October, caught as it was at the sharp end of the pounding match of 1st Ypres where the ability to both keep the Germans at bay and protect the infantry was critical. The artillery had “phenomenal accuracy”,290 fought hard (including the use of an armoured train sent out from Ypres)291 and sought to protect the infantry as best it could.292 (It was not all good; there was also inevitably friendly fire on such a confused battlefield.)293 However, by 25th October, whilst “British artillery had done valuable work [it] was running dangerously short of ammunition”,294 to the extent that on 24th October French was forced to warn the War Office that the artillery was receiving “only seven rounds per gun per day”295 from England and that the army might soon be without artillery support. Indeed, the lack of artillery support provided to the troops in the line (“by day, the gaps could be covered to some extent by artillery”)296 rather undermines the Official History`s cheery suggestion that “the artillerymen always managed to have rounds available at the right place at critical moments”.297

With this impediment, the British were confronted by a German artillery arm that seemed to have no such supply issues and it is clear that the British were not expecting the sustained ferocity of the German artillery that was to be one of the characteristics of 1st Ypres. For example, IV Corps noted that on 23rd October, along “the line held by the 7th Divn..throughout the day…the trenches were subjected to continuous heavy shell fire”,298 and similarly, the 2nd Border Regiment299 “reckoned that two German shells had landed on their trenches every minute from dawn to dusk for three days from 24 to 26 October, their casualties averaging some 150 a day”;300 every time the 2nd Yorkshires were “blown out of one trench, they moved into the next”.301 Many of the regimental diaries record heavy shelling every day they were involved in the battle. In some respects therefore, the quality/quantity position with the artillery mirrored that with the infantry. At this stage in the war, the professional gunners of the Royal Artillery were better than their German opponents (whose “state of gunnery training…was truly woeful”)302 and the best of their equipment matched the German guns. However, they were outnumbered, as well as restricted in their fire rate because of the shell shortage. Insofar as it seems contrary to compare the British infantry favourably against their counterparts when 7th Division incurred such high casualty numbers, the explanation lies in the devastating effect of the German guns;303 Capper, for example, commented on 20th October in relation to casualties in 22nd Brigade that “these casualties were almost entirely caused by shell fire to which our artillery found great difficulty in replying.304 This is echoed in the Official History:

“In the main the casualties were the inevitable consequence of the overwhelming superiority of the enemy`s heavy artillery, and of the task successfully carried out by the division, of meeting the first onslaught of the numerically stronger young German divisions, on a front of considerably over five miles in which was included an awkward salient.”305

The Divisional War Diary History has numerous accounts of units being shelled out of trenches that were completely destroyed.306 Indeed, “of all wounds inflicted on British troops throughout the war, 58.51% were by shell or mortar bomb”,307 and exposed in unsatisfactory trenches as they were for so much of the battle, 7th Division suffered grievously. “Every day the shallow trenches had been blown in,308 and every night was spent in their reconstruction, with the result that the troops had but little rest, either by day or night, whilst the casualties mounted up without interruption”.309 The “sheer volume of German fire310 demoralised British troops not yet accustomed to prolonged bombardment”311 (such as the 36 hour shelling of the Kruiseke salient which finally compelled the British to withdraw). If the terrain (see above) had been better for artillery (“the Germans did not have good observation of the British positions, which was probably just as well, as the defences were very thin”),312 then Capper`s men might well have been shelled all the way back to Ypres.313

To again utilise the factors suggested by Millett and Murray, the assessment of “relative effectiveness” between the British and German artillery is less clear cut than in the case of the infantry. Whilst it does again seem that British were the more professional, sheer weight of numbers (emphasised by the shell shortage) hindered their ability to dominate the battlefield as they would have wanted, and the numeric advantage of the Germans inflicted heavy casualties on (particularly) the infantry of 7th Division. This leads to a conclusion that notwithstanding its inherent quality and professionalism, in playing its part in the defence of Ypres, the artillery of 7th Division was not as effective as it could have been because it did not have the fuller complement of guns enjoyed by the earlier divisions of the BEF nor the amount of ammunition it really needed.

CONCLUSION

How then should history judge 7th Division at the 1st Battle of Ypres?

This dissertation has sought to take the methodical approach suggested by Millett and Murray (considered in conjunction with the factors suggested by the SHLM Project) to undertake a reasoned analysis of 7th Division between 27th August and 7th November 1914 so as to firstly, try and assess its effectiveness during 1st Ypres and, secondly, by looking at the German army it faced, to draw some conclusions about its relative effectiveness.

Chapter 2 identifies a number of factors which detracted from the effectiveness of 7th Division. If one accepts that the course of the war was going to place 7th Division at the eastern approaches to Ypres in mid-October, the paradigm situation of course would have been if it could have arrived as a fresh, full complement division, well-trained as a unified formation, with the 1914 standard artillery and a level of ammunition sufficient to enable it to sustain a long and intense battle. However, for the reasons discussed above, whatever its real or perceived attributes, it reached Belgium with leadership, training and equipment deficiencies. Once in Belgium, by train, motor, wagon and foot, the division embarked on an exhausting series of movements which ensured that by the time it got to Ypres, it was already fatigued. It was then ordered into aggressive defensive positions with a length of line which badly over-extended the division. It then took casualties and further depleted its physical resources in a series of ill-considered attacks (in part based upon an inadequate use of available intelligence) that could never have succeeded; moreover, it is arguable that the time and effort expended in these engagements, and the grimly inevitable manoeuvre back to a shorter line, deprived the division of the opportunity to construct substantive earthworks and other defensive positions at positions of its own choosing (whichever was the preferred slope of siting). This would then have given the division the best opportunity to repel the German advance. These combined factors inevitably reduced the effectiveness of the division.

Chapter 3 begins by looking at terrain, seemingly a factor which would affect both armies, but in fact concludes that on balance the nature of the ground in 1914 worked to the advantage of the British defenders. It then considers leadership within 7th Division and suggests that whilst Capper had some very real flaws, given the desperate defence required of 7th Division at 1st Ypres, Capper`s aggressive stance, combined with strong junior leadership, worked in those very particular circumstances and therefore enhanced the fighting power and effectiveness of the division. (Whether Capper could have developed as a better and more conventional commander as the war went on is conjecture but it seems unlikely given the manner of his death and the increasing negative comment his personality had started to attract.)

Finally, Chapter 3 also examines the qualitative differences between the key fighting forces (infantry and artillery) of 7th Division and the opposing German Fourth Army and it is in this respect that both the objective “effectiveness” and the real “relative effectiveness” of 7th Division can be seen. The ground had to be held and, whilst the German forces had been “numerically vastly superior…too many troops had been trained in haste…and [they were] faced with a potent combination: a small but highly professional force of British regulars, well led, and even in defence inculcated with the spirit of the offensive”.314 Rawlinson was to comment of the Germans that “even if the greater part of the attacking infantry consisted of newly raised troops, the determination of their attack in spite of very heavy losses, and the powerful artillery support behind them, rendered them most formidable opponents”.315 All the evidence supports the conclusion that the division was effective in objective terms but also, man for man, it was also (notwithstanding undoubted valour of the German troops) more effective than the forces that opposed it.

Interestingly, what however is still not clear in this examination of relativity is the extent to which we would change or refine our assessment if we could empirically calculate the effect that the use of forward slope trenches really had – did they result in significantly higher German casualties, albeit at a price of high British casualties? If the British trenches had been on rear slopes, would they have been more easily over-run by the Germans? There does not appear to be enough evidence to answer this definitively, and it remains a controversy of 7th Division`s engagement at 1st Ypres. However, weighing the many discussions on this, one gets the sense that it would not change the more fundamental conclusions about the relative effectiveness of the qualities of the British defenders and German attackers.

One should also not discount luck as a factor. The Gordon Highlanders historian comments that “those who follow [the battle`s] course with care are again and again brought up by the inability of the Germans to exploit their gains against the British and the French…allowed to escape almost daily by the German Army, which is enterprising by tradition and in 1914 was aflame with zeal to conquer”.316 Part of the “luck” was due to the terrain, and the protection of the tree cover in particular (impairing German observation of the British deployment), but there were a number of times in the battle where control had passed to the Germans and they failed to take their opportunities. This does not detract from the stated skills of 7th Division`s men, but they were close on a number of many occasions to being gallant losers rather than dogged winners.

At its most basic level, in a military context, effectiveness is about achieving objectives, and Capper`s task of protecting Ypres was clearly spelt out in the order from Montgomery at IV Corps on 14th October (“You will be responsible for the defence of the town..”).317 On this narrow basis, 7th Division was effective because although it had retreated, and was finally relieved, it had not collapsed and played the largest part in holding the line. The other British forces had played their parts, and the French had helped, but it was Capper`s men who stuck it out, holding ground and buying time. Ypres did not fall, but it came with a terrible price. Anthony Farrer-Hockley was to write of Ypres that “the old British Army with its venial faults and marvellous quality had died there in its defence”.318 The Official History writes that 7th Division left the line “a mere wreck of the fine force which had landed in Belgium…its fighting power nearly exhausted but its fame, like that of the original five divisions, secure for all time”.319 Capper and his men had become the “immortal 7th Division”,320 but its fighting men were now of a “pitiable appearance”321 and had been reduced from 14,000 to 4,000 in four weeks. “The BEF`s losses in proportion to the size of the force remained staggering”,322 and history should set 7th Division, quite rightly, in its proper place as part of the Old Contemptibles.

The last words must go to the historian of the Northumberland Hussars:323

“The marvellous discipline of the regular army asserted itself, and those magnificent men fought with no less courage and resource under the command of a lance-corporal or a senior private than when commanded by a Colonel or a Captain. To such men nothing was impossible”.

The Immortal 7th Division

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives

The Capper Papers at the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives, King`s College, London:

- Text of lecture by Thompson Capper on “The principles of strategy”, an exercise set to the senior division at the Staff College, Quetta, June 1908; and

- Text of lecture by Thompson Capper dated 29th February 1912 to the members of the Royal Military Society, at Dublin on the subject of “Staff duties”.

The National Archives

Various WO 95 referenced papers at the National Archives (all digitalised unless indicated otherwise):

Corps

TNA WO 95/706 – IV Corps War Diary (not digitalised), including:

- War Diary

- Sir Henry Rawlinson`s Report on IV Corps of October 1914

- Appx B (Reports Received & Sent as to Progress of Operations)

- Various orders

- Intelligence Summary for October 1914 (Captain C.O. Place)

Division

TNA WO 95/1627/1 – 7th Division War Diary (October 1st -31st 1914)

TNA WO 95/1627/2 – 7th Division War Diary (November 1st -30th 1914)

Divisional Cavalry

TNA WO 95/1642/1 - Northumberland Hussars

Artillery

TNA WO 95/1642 - XIVth Brigade R.H.A.

20th Brigade

TNA WO 95/1650/1 – 20 th Brigade War Diary

TNA WO 95/1657/2 – 1st Btn Grenadier Guards

TNA WO 95/1657/3 – 2nd Btn Scots Guards

TNA WO 95/1655/1 – 2nd Btn Border Regiment

TNA WO 95/1656 – 2nd Btn Gordon Highlanders

21st Brigade

TNA WO 95/1658/1 – 21st Brigade War Diary

TNA WO 95/1658/1 and 2 – 2nd Btn Bedfordshire Regiment

TNA WO 95/1659/4 –2nd Btn Yorkshire Regiment

TNA WO 95/1659/2 – 2nd Btn Royal Scots Fusiliers

TNA WO 95/1659/3 – 2nd Btn Wiltshire Regiment

22nd Brigade

TNA WO 95/1660/1 – 22 nd Brigade War Diary

TNA WO 95/1664/1 – 2nd Btn The Queen`s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment

TNA WO 95/1664/3 – 2nd Btn Royal Warwickshire Regiment

TNA WO 95/1665/1 – 1st Btn Royal Welch Fusiliers

TNA WO 95/1664/2 – 1st Btn South Staffordshire Regiment

The Imperial War Museum (Department of Documents)

The R.H.D. Tompson Papers

Official Histories

Edmonds, J.E., (ed.) Official History of the Great War: Military Operations France and Belgium (London 1922-48, 14 vols)

Atkinson, C.T., The Seventh Division 1914-1918 (London 1927)

Wynne, G.W., Ypres 1914: An Official Account Published by Order of the German General Staff (titled Die Schlacht an der Yser und bei Ypern im Herbst 1914 in the original German version) (London 1919)

Regimental Histories

Buchan, J., The History of the Royal Scots Fusiliers (1678-1918) (London 1925)

Dudley Ward, Maj. C.H., Regimental Records of the Royal Welch Fusiliers Vol III 1914-1918 (London 1928)

Falls, C., The Gordon Highlanders in the First World War 1914-1919 (Aberdeen 1958)

Jones, J.P., A History of the South Staffordshire Regiment (1705-1923) (Wolverhampton 1923)

Loraine Petre, F., Ewart, W. and Lowther, Maj.-General Sir Cecil, The Scots Guards in the Great War, 1914-1918 (London 1925)

Pease, J.P., The History of the Northumberland (Hussars)Yeomanry (1819-1919) (London 1924)

Ponsonby, Lt.- Col. The Right Hon. Sir Frederick, The Grenadier Guards in the Great War of 1914-1918 (London 1920)

Wylly, Col. H.C., The Border Regiment in the Great War (London 1924)

Wylly, Col. H.C., The Green Howards in the Great War (London 1926)

Wylly, Col. H.C., History of The Queen`s Royal Regiment Vol VII (London 1925)

Official Publications

The General Staff, Notes on Field Defences (London 1914)

Books, Articles and Theses

Arthur, Sir George, Life of Lord Kitchener (London 1920, Vol I)

Arthur, Max., Forgotten Voices of the Great War (London 2002)

Ascoli, D., The Mons Star (Edinburgh 2001)

Atkinson, C.T., The 7th Division, 1914-1918 (London 1927)

Barton, P, Passchendaele – Unseen Panoramas of the Third Battle of Ypres (London 2007)

Beckett, Ian F.W., Ypres – The First Battle 1914 (Harlow 2006)

Beckett, Ian F.W. and Corvi, Steven J., Haig`s Generals (Barnsley 2006)

Binding, R., A Fatalist at War (London 1929)

Bond, B., N., The Victorian Army and the Staff College, 1854-1914 (London 1972)

Bond, B. and Cave, N., Haig – A Re-Appraisal 80 Years On (Barnsley 2009)

Brown, M., The Imperial War Museum Book of the Western Front (London 1993)

Caffrey, K., Farewell, Leicester Square – The Old Contemptibles 12 August – 20 November 1914 (London 1980)

Cassar, G.H., Kitchener`s War – British strategy from 1914 to 1916 (Dulles USA 2004)

Cassar, G.H., The Tragedy of Sir John French (London 1985)

Cave, Nigel, Polygon Wood (Barnsley 2011)

Clark, A., The Donkeys (London 1961)

Corrigan, G., Loos 1915: The Unwanted Battle (Stroud 2006)

Corrigan, G., Mud, Blood and Poppycock – Britain and the First World War (London 2003)

Davis, W., Into the Silence – The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest (London 2012)

De Groot, Gerard J., G., Doulas Haig 1861-1928 (London 1988)

Dixon, J., Magnificent but not War: 2nd Ypres (London 2003)

Farrar-Hockley, A., Death of an Army (New York 1968)

French, Field-Marshal Viscount of Ypres, 1914 (London 1919)

Gardner, Nikolas, Trial by Fire – Command and the British Expeditionary Force in 1914 (Westport USA 2003)

Griffith, Paddy, Battle Tactics of the Western Front 1916-18 (London 1994)

Griffith, Paddy, (ed.) British Fighting Methods in the Great War (London 1998)

Hamilton, E., The First Seven Divisions: Being a Detailed Account of the Fighting from Mons to Ypres (New York 1916)

Harris, J.P., Douglas Haig and the First World War (Cambridge 2008)