The Use of Wireless at the Battle of Amiens 8 - 11 August 1918

- Home

- World War I Articles

- MA Dissertations

- The Use of Wireless at the Battle of Amiens 8 - 11 August 1918

The Use of wireless at the Battle of Amiens 8 - 11 August 1918

Author: Andy Powell MA

A dissertation submitted as part of the requirements for the degree of MA in British First World War Studies at the University of Birmingham. This work won the WFA's prize for the best dissertation of 2013 which was awarded at the WFA President's Conference of 2014.

Introduction

- Chapter 1 Signals Intelligence: The plans for secrecy and deception

- Chapter 2 The use of wireless with the ground forces

- Chapter 3 The use of wireless with the Royal Air Force

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

Abbreviations

- ADM Admiralty.

- AFA Australian Field Artillery.

- AIR Air Ministry.

- AWM Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

- BEF British Expeditionary Force.

- CBSO Counter Battery Staff Officer.

- CCHA Canadian Corps Heavy Artillery.

- CW Continuous Wave.

- GHQ General Headquarters (of the BEF).

- GOC General Officer Commanding.

- HQ Headquarters.

- IWM Imperial War Museum, London.

- LHCMA Liddle Hart Centre for Military Archives, London.

- NAC National Archives of Canada, Ottawa.

- O.A.D Official Army Despatch.

- OR Other Ranks.

- RA Royal Artillery.

- RAI Royal Artillery Institute, London.

- R.A.F. Royal Air Force

- RFA Royal Field Artillery.

- RFC Royal Flying Corps.

- TNA National Archives, London.

- WT Wireless Telegraphy.

- WO War Office.

Introduction

There is a general consensus amongst historians that the Battle of Amiens marked the beginning of the end on the Western Front during the First World War.[1] The object of this dissertation is to examine the role and contribution of wireless communication to the success of the British Expeditionary Force (hereafter BEF) in the four days from August 8 to 11, 1918.

The significance of Amiens and wireless communication

Despite the consensus mentioned above, the British Official Historian, Brigadier-General Sir James Edmonds, opined that the success gained at Amiens was only 'what the Germans would call an ordinary victory'.[2] Edmonds went on to clarify this statement by explaining that, although Amiens was not a strategic victory, it did nonetheless deal the German Army a decisive blow to their morale, which resulted in a loss of faith in final victory.[3] However, it is probably more accurate to state that Amiens exacerbated the decline of morale in the German Army, a decline that had begun in the period following the failed March offensives.[4] This is confirmed by General Erich Ludendorff who although referring to 8 August as 'The Black Day of the German Army', believed that it was the prior loss of discipline and fighting capacity that had been the root cause of the collapse.[5] This loss of discipline was certainly evident at Amiens, a measure of which can be gained from the number of prisoners taken by the BEF; more enemy troops were captured in the six days from August 6 to August 12 than in the previous nine months combined.[6] Amiens did therefore deal the German Army a decisive blow and as a result 8 August is deserving of the title coined by Charles Messenger: 'The Day We Won the War'.[7]

Paddy Griffith has argued that it was the failure of communications on the Western Front that was the limiting factor in achieving a decisive break-through.[8] Although Amiens was not a 'break-out' battle, it was nevertheless a successful 'break-in' during which communications played an important part. A measure of this importance can be gained from statistics relating to Fourth Army's telegraph traffic, which show that from 8 – 11 August there was an average of 6,100 telegraphs handled per day.[9] No breakdown of these figures is available but it is likely that the majority were handled by the ground and poled cable network rather than by wireless.[10] However, ever since the March retreat it had been recognised that wireless was an essential means of communication in mobile warfare.[11] Consequently a number of measures were adopted in the early summer of 1918 to force the integration of this technology into standard signalling policy. These included the allocating of certain days to be used solely for wireless communications and practice days to simulate the use of wireless in mobile warfare.[12] Amiens was the first real opportunity to determine whether this newfound confidence placed in wireless was justified.

Historiography

Even though the success at Amiens ultimately led to victory in the west this period of the First World War is strangely neglected, Britons preferring to remember the 'mud and blood' of the battles of 1916 and 1917.[13] Jonathan Boff has shown that this culture extends to historians in that 24 works of military history were published on the 90th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme compared with only four on the 90th anniversary of the 'Hundred Days'.[14] One of the more obvious explanations for this dearth of historical works is the almost morbid fascination with the tragedy of war but Sydney Wise suggests that British historians have avoided this period due to its dominance by Dominion success.[15] The former is more plausible than the latter. A number of authoritative works do exist though, particularly concerned with the period of the Hundred Days, perhaps the most definitive of which is The Story of the Fourth Army by Major-General Sir Archibald Montgomery.[16] This work is written from a unique personal perspective with the author having privileged access to a wealth of original documents and as such it is rich in operational detail. However, it is distinctly lacking in detail with regards to communications and signalling. More recent secondary works fare no better in this regard, examples being Amiens to the Armistice and The Day We Won the War.[17] For instance, the latter does not mention the work of kite balloons or artillery aircraft, both of which used wireless extensively in the battle, this is despite a chapter dedicated to air operations.[18] Surprisingly, a similar criticism can be levelled at the Official History of the R.A.F. during the First World War.[19] The three national Official Histories also contain a paucity of references with respect to wireless, there being only 10 in total; three British, three Australian and four Canadian.[20] The latter does go into a reasonable amount of detail regarding the deception plan at Amiens, which is the subject of Chapter 1, but provides little information concerning the wireless aspect of the plan.[21] A comprehensive history of the work of the Signal Service was written in 1921 and until recently this work remained the authoritative text. However its staccato narrative makes for a difficult read and was described by Paddy Griffith as 'positively the most impenetrable book ever written on the war'.[22] A distinctly more modern and readable study is Brian Hall's Ph.D. thesis on communications, which Jonathan Boff suggests will replace Priestley's and become the 'standard work'.[23] Although this work contains a 20-page chapter on communications at the Battle of Amiens, within which wireless is discussed in some detail, there is no measurement of its importance during the battle.[24] Hall's later work, which is dedicated to wireless communications, describes the 'learning curve' in relation to the importance of wireless to the mobile battle and its viability as an alternative to cable.[25] The limitation of this work is that it is wide in scope and therefore is unable to dwell on particular actions or engagements; Amiens is only mentioned briefly in the broader context of the Hundred Days.

Primary Sources

The majority of the material used in this dissertation is contained within the various War Diaries at the National Archives, London. However, there are several gaps in these records, the largest of which are in connection with the wireless observation groups, signal schools and code breaking; of the latter only 25 of the 3,330 files have survived.[26] In addition, there is only one diary remaining from the army signal schools and only one from the wireless observation groups; both relate to the Middle East theatre and contain no useful information.[27] Personal papers and memoirs have been found to be useful although there is a distinct lack of memoirs in relation to wireless personnel.[28]

Structure

This dissertation will attempt to measure the effectiveness of wireless during the battle by analysis of three main subjects each with its own chapter. Chapter 1 will examine the importance of signals intelligence to the secrecy plan and what contribution it made to the fundamental objective of maintaining the element of surprise. The British Official History refers to this element of surprise as 'the essence of the Allied success'.[29] The key questions to be addressed in this chapter therefore are first, how important was the element of surprise to the overall success of the battle and second, what part did wireless play in maintaining the element of surprise? In order to answer these questions the secrecy plan will be broken down into three component parts namely; the feint at Kemmel in Flanders, the feint at Arras, and the measures taken on the Fourth Army front at Amiens.

Chapter 2 will focus on a the use of wireless by the ground forces, including infantry, artillery, tanks, as well as ancillary formations such as the field survey companies. One of the key objectives of this chapter is to provide information that can assist in determining whether there is a relationship between combat effectiveness and the use of wireless. The initial problem is to determine which troops were the most combat effective. The Dominion troops gained a reputation as elite troops on the Western Front and; this reputation was reinforced by Sir James Edmonds who believed that the Australian and Canadian officers and n.c.o's demonstrated superior leadership qualities in relation to their British counterparts.[30]Peter Simkins suggests that Edmonds criticism of British junior leadership is unjustified and has launched a convincing defence of British divisions.[31] Simkins cites the average success rate in opposed attacks for the nine British divisions who served in Fourth Army during the Hundred Days as 70.7 per cent.[32] This is identical to the figure for the five Australian divisions and similar to that of the four Canadian divisions, the latter achieving 72.5 per cent.[33] This comparative study of the combat performance of the British and Dominion divisions in Fourth Army will be mirrored with respect to the use of wireless in this dissertation. One of the problems faced in compiling this chapter was the paucity of primary sources in relation to the British divisions that took part at Amiens. This is in complete contrast to the Canadian and Australian records that contain a wealth of detailed information, which makes a comparison difficult. The key questions to be addressed in this chapter are first, to what extent was wireless used with the ground forces at Amiens, second, how does the use of wireless compare between the Dominion and British divisions and third, how important was wireless in the overall communications scheme.

Chapter 3 will examine the use wireless by the R.A.F., specifically aircraft and kite balloons. These balloons have received little attention from historians despite being a key component of the artillery counter battery function as well important gatherers of intelligence both at a tactical and operation level. This chapter will show that balloons were actually responsible for the neutralisation of more hostile batteries by wireless than dedicated artillery aircraft during the battle. This is despite the fact that artillery aircraft had been using wireless extensively since 1917 as Bidwell and Graham have observed:

By 1917, as 90 per cent of counter battery observation was done by airmen using wireless, the success of the artillery battle had come to depend on the weather being suitable for flying, on wireless reception and on a network of telephone lines from the receivers to the users of the airmen's information.[34]

The key questions that will be examined in this chapter are first, to what extent was wireless used with the air forces and second how important were these wireless equipped craft to the overall effectiveness of the artillery function.

In summary this dissertation will add to the historiography of both the Battle of Amiens and communications by examining the use of wireless in the most decisive battle of the First World War. Tim Travers has argued that technology was more important than tactics when it came to the combination of arms in 1918; this is perhaps going too far but there is little doubt that technology when used correctly is important in warfare.[35] This dissertation will show that the BEF was using new technology such as wireless to good effect and attempting to integrate it into an evolving weapons system. It will also show that wireless was a useful but not essential component of that system.

Chapter 1

Signals Intelligence: The plans for secrecy and deception

On 17 July 1918 General Sir Henry Rawlinson, GOC Fourth Army, wrote to GHQ outlining his proposals for the offensive and emphasizing the importance of secrecy:

The success of the operation will depend to a very great extent, as was the case on the 4th July, on effecting a complete surprise. Secrecy, in my opinion, is therefore, of vital importance and must be the basis on which the whole scheme is built up.[36]

The measures used to bring about surprise form the basis of the discussion in this chapter, particularly with respect to wireless. In addition, an attempt will be made to determine how effective these measures were and what contribution they made to the overall success of the operation.

The plan to bring about surprise at Amiens was highly complex but the majority of its components were encapsulated in three operational documents, two of which were issued by GHQ and one by Fourth Army.[37] At this stage of the war GHQ was exercising much more control over matters of operational security and pursuing a 'definite policy' of misleading the enemy.[38] The plan was essentially in three parts, namely preparations for a feint attack at Kemmel, preparations for a feint attack at Arras and finally, matters pertaining to general operational security. An overview of these plans can be seen in the charts below.

The Kemmel feint was not only aimed at deliberately misleading the enemy as to the location of a potential offensive but more importantly, it was designed to camouflage the movement of Canadian Corps from Arras to Amiens. With a fighting strength of 118,000 men the Canadian Corps was the largest Corps in the BEF and they were well known to the Germans as attacking troops.[39] As Rawlinson noted shortly after the battle: 'wherever the Canadian Corps was identified by the enemy, he would certainly expect an early offensive'.[40]

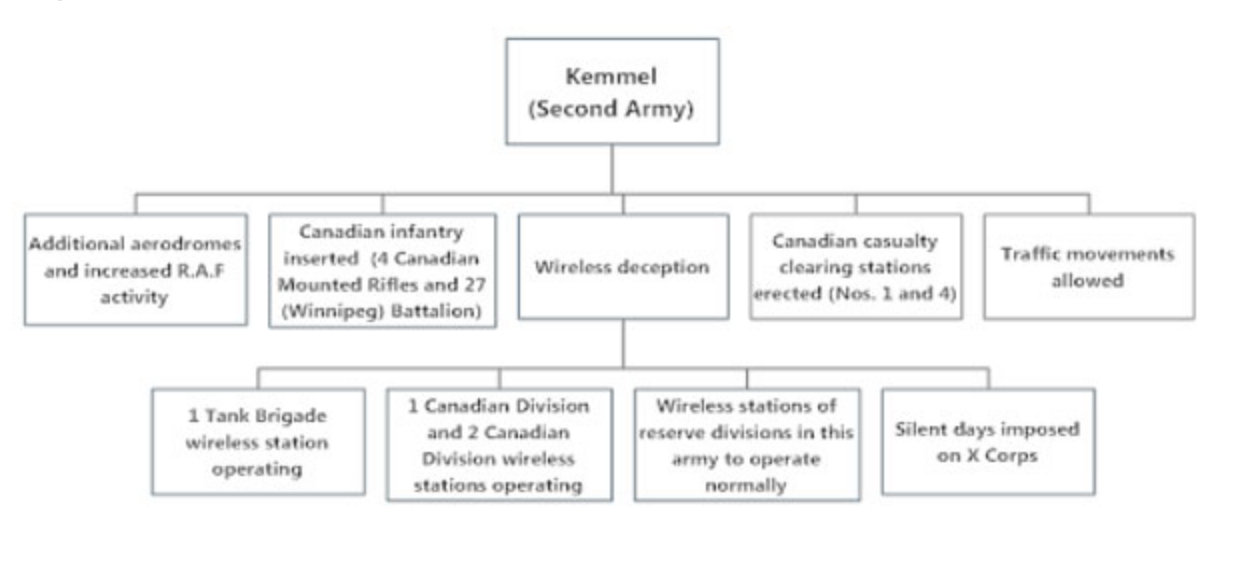

Diagram 1.1: The Kemmel Plan

This plan, issued on 27 July, involved the Canadian and Tank wireless sets along with their respective operators, two Canadian infantry battalions, and two Canadian casualty clearing stations, all being relocated from First Army to Second Army.[41] In addition the R.A.F. was ordered to make arrangements with Second Army for occupation of additional aerodromes and to steadily increase aerial activity on this front up to two days before the battle.[42] The object of these arrangements was:

...to give colour to a plan for the interpolation of the Canadian Corps into the line with a view to delivering an attack. The wireless stations will operate and the Battalions be put into the line.[43]

It was hoped that this would give the impression of an advanced party paving the way for the imminent arrival of the whole Canadian Corps and to make this seem more convincing false movement orders were issued on 28 July.[44] The historian S.F. Wise has commented that the measures of deception used to hide the movement of the Canadian Corps are well known.[45] This is not strictly correct as although many abridged accounts have appeared in historical works they tend to be based almost entirely on information contained within the Official Histories, are lacking in detail and contain a number of inaccuracies. For example, Tim Travers incorrectly states that when the Canadian Corps moved to Fourth Army they disguised their move by 'leaving their radio units behind'.[46] The source of this inaccuracy is probably Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson who, in an uncharacteristic misquote of the Canadian Official History, state that 'dummy wireless stations were set up at Arras'.[47] The Canadian Official History correctly places these dummy wireless stations in Flanders.[48] However, it is not only the location of the wireless stations that is incorrectly cited but also details of the actual units that took part. For instance, Shane Schreiber states that these units were the Canadian Corps wireless section; they were however divisional units as instructed in the operational orders.[49] Some confusion on this point is justified though as it is difficult to extract a definitive answer from the war diaries regarding exactly which units were involved. The diary of the 1 Canadian Divisional Signal Company states that orders were received from First Army on 30 July to send the headquarters wireless set, along with wireless operators, to Flanders and that X Corps took receipt later that day.[50] The 1 Canadian Division's after action report confirms this but adds that it was the wireless sets of all four Canadian divisions that were sent north to Second Army.[51] However, there is no mention of this in the respective war diaries of those other divisions. Further confusion arises as a result of an entry in the GHQ war diary, which contains an instruction to Second Army, dated 2 August to immediately return the 2 Canadian Divisional wireless sets to Fourth Army.[52] This diary though makes no mention of any other Canadian divisional sets, including those of 1 Canadian Division.[53] This leaves two possible explanations, either one of the GHQ or 1 Canadian Division war diaries could be in error, or both the 1 Canadian and 2 Canadian divisional sets were sent and the GHQ instruction regarding the 1 Canadian divisional set was either omitted or not required. The latter is the most likely as the original instruction to send the wireless sets to Second Army asked for 'two Canadian Divisional Wireless Sets'.[54] The Director of Second Army Signals war diary does record receipt of two wireless sets from First Army but erroneously gives the date of receipt as the 25 July, which is two days before the initial instruction from GHQ was sent out.[55] Further weight is added to the wireless sets being from both the 1 and 2 Divisional Signal Companies as both of their war diaries make specific reference to X Corps on consecutive days. Although the diary of the 2 Divisional Signal Company does not make reference to a wireless set being dispatched it does record that a visit was made to X Corps on 29 July by its commanding officer as well as one other officer.[56]

The final inaccuracy with regard to the movement of the Canadian divisional wireless sets and their operators concerns what happened to them after arrival in Second Army. Daniel Dancocks suggests that they were assigned to Sydney Lawford's 41 Division but examination of that division's war diary reveals that it was American and not Canadian wireless personnel that were attached to that division on 29 July.[57] Evidence in support of these men being American is compelling due to the fact that the Second Army war diary records four battalions of American infantry beginning their attachment to 41 Division and 6 Division on 26 July.[58] Furthermore 41 Division was allocated to XIX Corps and not X Corps. As neither the X Corps war diaries nor its associated divisional war diaries contain any reference to the Canadians and their wireless sets, their attachment within Second Army remains a point of conjecture. Once established with Second Army it is not entirely clear what messages the Canadians sent, to whom they were sent and in what format they were sent. Regarding the latter, once again there is an ambiguity as Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie, GOC Canadian Corps, wrote that the messages were sent 'worded so as to permit the enemy to decipher the identity of the senders' whereas an after action report draft narrative states they were sent 'in clear'.[59] The latter would probably have raised too much suspicion, as the Germans were well aware that the BEF only sent messages in clear in emergencies.[60] One of the most likely methods that could have been used by the Canadian signallers to allow their identity to be discovered would have been to have reverted back to the insecure call sign system that had been replaced in First Army in May 1918. This system identified a formation by three letters such that the letters "AUO" would represent the Australian Corps and the "CAO" the Canadian Corps.[61] In addition, it would have been possible for the Germans to identify these units by the wavelength they employed. This had been recognised by GHQ by 5 August 1918 who were working on a system to allot new wavelengths although this was not done in time for the battle.[62]

The tank wireless sets were supplied by the 1 Tank Brigade Signal Company, whose war diary records that on 1 August 'Lt Mainprize and 10 OR's were sent for special wireless duty in Second Army area'.[63] Despite the fact that these men were performing this 'special duty' for nine days before returning to their unit very little information is available regarding the exact nature of their work. The British Official History simply records that 'great activity was exhibited by the wireless stations of First and Second Army on the tank wavelength which was well known to the Germans'.[64]

As the orders in Second Army area were being enacted a simultaneous plan was being put into effect on the front of First Army in the region of Arras.

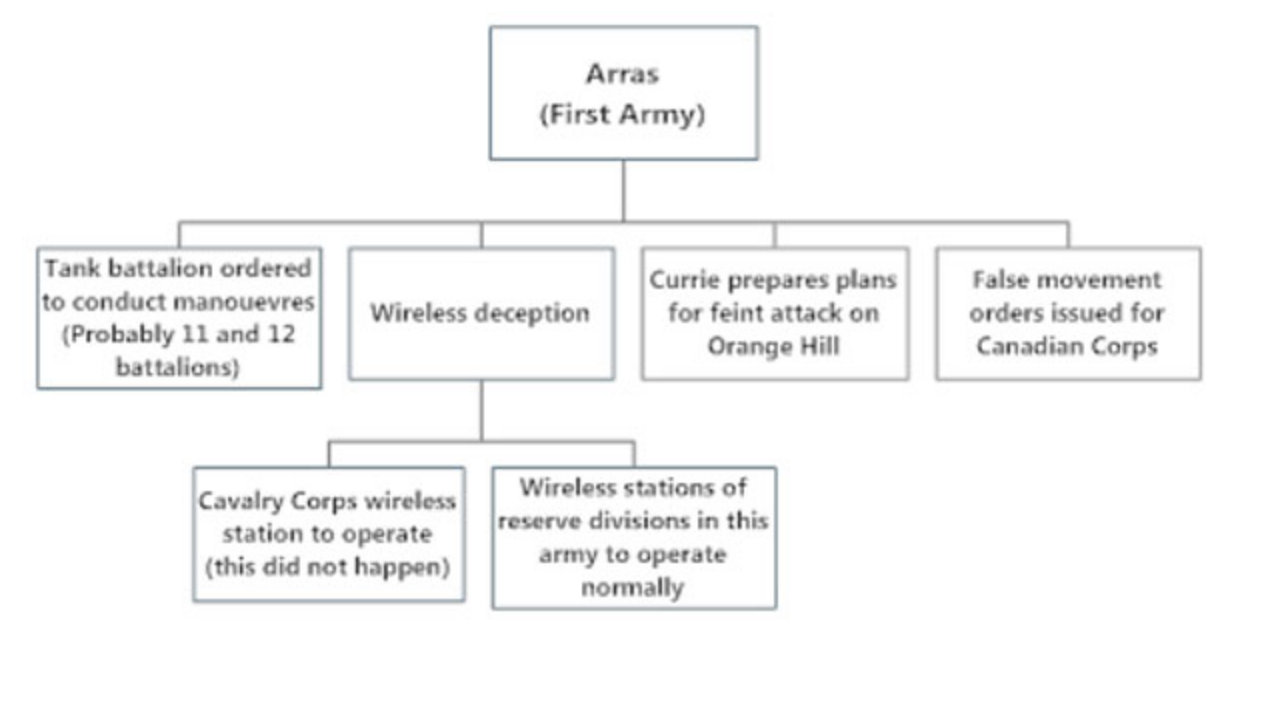

Diagram 1.2: The Arras plan

The instructions contained in the Annexure to O.A.D 900/1 regarding this part of the deception plan read:

Every effort will be made by the First Army to foster the belief, which appears to exist, that an attack is imminent in the ARRAS sector.[65]

To assist this effort, on 27 July the First Army was instructed to make arrangements for one cavalry wireless set to be operated behind the Arras front.[66] Additionally, the wireless sets of the reserve divisions of First Army, together with those of the Second and Third Armies, were instructed to be setup and operated behind their respective fronts whilst wireless activity on all other fronts was ordered to cease.[67] The cavalry orders were changed on 30 July when instructions were given that only in the event of a relocation of the Cavalry Corps headquarters would the Corps wireless station be moved to First Army area.[68] Despite these instructions they were never implemented and instead the Cavalry Corps wireless duty station was simply dismantled under orders from GHQ and did not begin operating again until 2.30 a.m. on the morning of 8 August.[69] This change is probably due to GHQ realising that a silent wireless station could be just as useful as a dummy station with respect to the falsification of signals traffic. Two other activities were taking place within First Army front to complete the deception plan on this front. Firstly, a tank battalion was instructed to carry out manoeuvres in broad daylight as if in preparation for an attack, and secondly, Currie was busying himself with false plans for a feint in the Orange Hill area near Arras. This feint was first proposed by Currie at a conference with Rawlinson on 21 July and was as much about convincing Canadian troops of an impending attack as it was about convincing the Germans.[70] The next day, on the 22 July, he outlined the dummy plans to his divisional commanders and, according to the Canadian Corps CBSO, Lt. Colonel Andrew Macnaughton, gave a very convincing performance.[71]

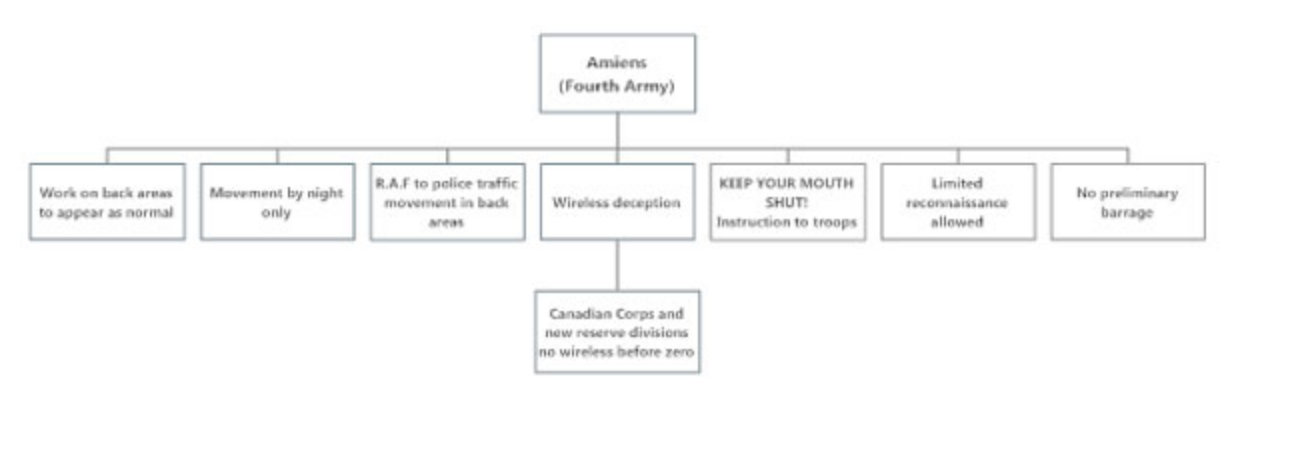

Finally, a series of general security measures were implemented prior to the opening of the offensive on 8 August these were designed to maximise the element of surprise. They included dispensing with the preliminary barrage and instead relying on accurate survey techniques and the mass use of tanks, the engine noise of which being cloaked by low flying aircraft, minimising unusual activity near the front line and pasting a notice in the men's pay books ordering them to 'keep their mouth's shut'.[72] Even the lie of the country favoured a surprise attack with its covered approaches.[73]

Diagram 1.3: The general secrecy measures at Amiens

Additionally, in July 1918, the wireless security measures adopted by the British Armies in France were revised and improved. The improvements involved the use of 'silent days' and an overhaul of the wireless call signs used by all formations. A 'silent day' was usually a 12-24 hour period within which the use of field telephones, power buzzers and wireless was strictly forbidden. It was well known that any abnormal communications silence or activity, particularly with respect to wireless was a 'sure sign' that an offensive was impending.[74] Silent days were therefore an attempt to obfuscate the conclusions that would otherwise be drawn from listening in to the BEF's signals activity. John Ferris suggests that these periods of silence were random but it seems much more likely that they were deliberately planned, particularly with respect Amiens.[75] For example, the war diary of 30 Division records only three silent days for the whole of 1918 and these occurred on 24 July, 1 August and 10 August. The 30 Division was part of X Corps during this period and although there is no record of silent days in that formation's war diary a wireless operator in 30 Division confided to his personal diary that 24 July was a 'silent day for the corps'.[76] It would therefore seem probable that 1 and 10 August would also have applied to the whole corps. The three silent dates fall just before, and during the Battle of Amiens, and given that X Corps were located within Second Army, who were the hosts of a wireless deception plan with respect to the Canadian Corps, this would seem to suggest that these days were part of a carefully orchestrated plan.

In addition to the silent days the system of calls signs underwent a radical change beginning in May 1918 when, according to a captured German document, four letter codes were introduced to identify units.[77] This same document also states that the Germans had succeeded in penetrating this system by July 1918 after which call signs were changed daily; these statements are quoted by John Ferris in his 1988 journal article.[78] A significant proportion of Ferris's article is based on this document, however the latter is fundamentally flawed for two reasons. First, what happened in May was not the introduction of four letter codes but rather the frequency of change became daily instead of bi-monthly, and second, in July it was not the daily change that was introduced but a much higher level of security through encryption of the call signs.[79] As a result, the statement that the Germans succeeded in 'penetrating this system' lacks credibility, as the system they claimed to penetrate was not the one in existence.[80] The conclusion that the Germans were not successful in penetrating the system of daily call sign changes is supported by another translated document, dated 1 August, from the German 51 Corps that noted 'a striking improvement has lately taken place in the telephone and wireless discipline of our enemies'.[81] This general tightening of wireless signals security ultimately helped facilitate the element of surprise at Amiens. How effective though were the other wireless deception measures at Kemmel and Arras and did they also succeed in their objective?

According to Sir Arthur Currie, when the offensive at Amiens was launched on 8 August the surprise was 'complete and overwhelming'.[82] Prisoners from four separate divisions, captured by the Australians early on 8 August, also stated that the attack had been a 'complete surprise'.[83] This is not entirely true as a number of prisoners captured on 8 August testified that two factors had led them to believe that an attack was expected, although not imminent; these factors were an increase in air activity and movement behind the lines.[84] The latter had been a concern of 2 Canadian Division who, prior to the battle reported:

.... a very large movement by day of heavy artillery and ammunition lorries. Although the visibility from the air was poor, it was certain that some of this movement was observed by the enemy.[85]

In addition, on 4 August the German Oberste-Heeresleitung reported that two Canadian divisions previously on the Arras front had been replaced and that this required particular attention to be paid to the fronts of the British Third and Fourth Armies.[86] A certain amount of suspicion was also raised by the communications silence that had preceded the attack.[87] It is interesting that no mention was made of the British Second Army front despite the fact that the Germans had established the presence of Canadian troops in Flanders.[88] The Australian Official History states that it was only the presence of Canadian Wireless and not infantry that was detected in Flanders, although the source of this assertion is unclear.[89] Ernst Kabisch states that both the presence of the two Canadian battalions and their wireless sets were detected, as does the German Official History.[90] Despite this the German Army staff did not update their situation maps, which, on the morning of 8 August, still showed the four Canadian divisions, clustered around Arras.[91] It is unlikely that this was as a result of the Orange Hill feint, it is probably more the result of incomplete intelligence confirming that the entire divisions had moved. The result of all of this uncertainty was that the German staff were confused, but not convinced enough by the deception plans to change their troop dispositions.[92] However, the uncertainty combined with the other secrecy measures was enough to give the offensive at Amiens a high degree of surprise, even if that surprise was not total. Prior and Wilson argue that the deception plans served only one purpose and that was that the Germans did not move their artillery positions.[93] They also argue that not enough time would have been available to improve the poor state of the defences and adding more troops to the front line would simply have increased the number of casualties.[94] Regarding the first point, the Germans did actually move their artillery positions back eight days before the battle as a direct result of the Australian raid on 29 July.[95] This made very little difference as 95 per cent of the German guns were still located prior to the battle.[96] The latter point regarding adding of troops is somewhat moot as the Germans would have been more likely to bring in Eingreif divisions as their defensive doctrine was based on elastic defence in depth which called for a weakly held front line and counter attack troops in the rear.[97]

Two Canadian authors have opined that the deception plans were a major factor in the success on 8 August.[98] These plans do appear to have at least confused the Canadian troops according to an entry in Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig's diary dated 7 August, which reads:

The move of some Canadian battalions and casualty clearing stations to our Second Army front seems to have quite misled the Canadian troops and many spoke of the "coming offensive to retake Kemmel"![99]

The evidence suggests though that the Germans were more confused than deceived by these plans. The wireless stations in Flanders do seem to have come to the attention of the Germans, even more so than the two infantry battalions according to the Australian Official History, which suggests that wireless did make a significant contribution to this confusion. Other wireless security measures such as the new system of wireless call signs, the introduction of wireless 'silent days' and instructions to the Canadian Corps not to open wireless stations before zero simply added to this confusion.[100] The result was that German intelligence did not detect the relocation of the Canadian Corps from Arras to Amiens.[101] This was the decisive factor in the surprise at Amiens.

Chapter 2

The use of wireless with the ground forces

This chapter will discuss the extent to which wireless was used by the ground forces during the Battle of Amiens. In order to facilitate this discussion, two questions will be posed namely; did the Dominion divisions use wireless to a greater extent than the Imperial divisions and how did the use of wireless as a communications medium compare with other forms of communication during the battle?

The official signals policy that applied at the Battle of Amiens was laid down eight months before in the training pamphlet S.S 191.[102] This recommended that in the case of a move from static to open warfare each advancing division should make use of 'as many means of transmission as circumstances will admit'.[103] It was recognised that it would not always be possible to connect divisional communication routes by telephone and therefore suggested a number of alternatives such as visual signalling, portable wireless sets, mounted orderlies and message carrying rockets.[104] Emphasis was placed on restoring telephone communications as soon as possible. Wireless though was a new science and, as John Terraine observed, was not a habit carried over from civilian life.[105] This made the staff reluctant to adopt wireless, despite the official endorsement in the training pamphlets; in addition, the certainty of buried telephone cables in static conditions had created an air of complacency. Since 1 April 1916 orders had been issued that cable must be buried to a minimum depth of six feet in order to ensure immunity from a 5.9-inch shell.[106] This reluctance persisted up to the Battle of Amiens as evidenced by an after action report from the 4 Canadian Signal Division:

In stationary trench warfare seven foot buried cable has made the telephone service so certain that all other methods of communication have become superfluous and it is only the keenest optimism that has maintained the efficiency of such alternatives as wireless, visual and cable wagons.[107]

Attempts had been made, during the early summer months, to encourage the use of visual signalling and wireless by the use of what became known as 'silent days'.[108] These days were the complete antithesis of those mentioned in the previous chapter in so far as they only allowed the use of wireless and visual, the use of the telephone and telegraph being strictly forbidden. Unfortunately these days were not always successful as recorded by an artillery officer in the 1 Canadian Divisional Artillery.[109] There were also significant inherent problems with wireless. These included a lack of trained operators, susceptibility to jamming, heavy weight of sets, conspicuous aerials and the problem of enciphering and deciphering each message.[110] Despite these problems wireless technology was improving rapidly in 1918 and this resulted in greater confidence in the medium. For instance the 1917 pattern 'spark' trench set, which became available in large numbers in 1918, was capable of transmitting on 16 wavelengths instead of just two.[111] A Canadian Corps wireless intelligence report suggests that by August 1918 the BEF's wireless technology was one year ahead of the Germans who had been suffering from material shortages.[112]

However, the use of wireless at corps, division and brigade level varied tremendously at Amiens as shown in the table below.

Table 2.1: The use of wireless between infantry formations

|

Corps - Division |

Division - Brigade |

Brigade - Battalion |

Forward of Battalion |

|

|

12 Division[113] |

Not required* |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

18 Division |

Not required* |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

58 Division |

Not required* |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

1 Canadian[114] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

2 Canadian[115] |

Yes (Jammed) |

Yes (Jammed) |

No |

No |

|

3 Canadian[116] |

12 Aug on |

12 Aug on |

Yes |

Yes |

|

4 Canadian[117] |

Vital |

Very useful |

No |

No |

|

32 Division[118] |

No report |

No report |

No report |

No report |

|

1 Australian[119] |

Not Required |

3 AIB - 9 Aug |

No |

No |

|

2 Australian[120] |

Yes (Jammed) |

Yes (Jammed) |

Yes |

13th Aug on |

|

3 Australian[121] |

Not Required |

Not Required |

Not Required |

Not Required |

|

4 Australian[122] |

Yes (Jammed) |

Yes (Jammed) |

Yes |

No |

|

5 Australian[123] |

Yes |

Quite successful[124] |

No |

No |

* 'Not required' means available but not called upon.

This information confirms Brian Hall's observations that the further a formation was down the chain of command the more difficult wireless communications became.[125] Forward of brigade the most commonly used wireless set was the so called 'loop' set, named after the design of it's aerial. The Canadians had only been issued with their sets a few months before Amiens and did not carry out their instructions that each battalion should train at least six signallers in their use.[126] Various excuses were made by the divisions to cover up this neglect such as 'the sets were too heavy' or the 'distances from battalion to brigade headquarters were too great'.[127] Although the former was a possibility due to the advances made, the latter was unlikely given that only two men were required to carry these sets.[128]

There is a paucity of information with regards to wireless in the war diaries of the Imperial divisions.[129] As a result, the information for the three divisions in III Corps has been taken from the latter formations after action report but this information should be treated with caution for two reasons. Firstly, according to an 18 Division report, wireless was 'very little used' during the battle and no mention is made of wireless between brigade and battalion.[130] The report is actually quite damning with respect to wireless and concludes with the statement 'this form of communication does not commend itself to the staff'. Secondly, the III Corps report states that all messages were sent in clear whereas the 18 Division report cites the disadvantages of enciphering and deciphering as a key reason why wireless was little used.[131] The sending of messages in clear at Amiens probably contributed to a degree of caution being exercised in the use of wireless in the months that followed.[132] The Canadian Corps though quickly learnt that the cipher was the enemy of wireless and as a result, of the 157 messages handled between corps and 1 Canadian Division from 8 – 12 August, 95 per cent were in clear.[133] The Cavalry Corps had also grasped the importance of abandoning the use of ciphers and recommended that 'every opportunity must be taken of doing so'.[134] The Cavalry Corps used wireless constantly at Amiens, relying on it almost totally on 8 and 9 August.[135]

The sheer volume of wireless sets used during the battle, estimated to be in the order of 200, meant that a certain amount of 'friendly jamming' was inevitable.[136] The Canadian Corps blamed this phenomenon on poorly trained telegraphists but this statement was probably made to deflect blame away from the main issues, which were lack of Corps control and the use of fixed wavelengths.[137] Every division in a corps used the same wavelength, in the case of the Australian Corps this was 350m, and therefore a certain amount of jamming was inevitable.[138] As a result it was recommended that each division should be allocated a separate wavelength and that brigade and battalion headquarters should be grouped to provide a single information channel.[139] Jamming problems also occurred when a division moved forward and it passed control of its brigades temporarily back to corps. This often resulted in a breakdown of wireless communications and at one stage the Canadian Corps directing station was attempting to control six brigades as well as four divisions.[140] The recommended solution was the issue of an additional trench set to each division to facilitate uninterrupted forward control.[141]

Some of the artillery brigades at Amiens were provided with Continuous Wave (CW) wireless sets, which were far more advanced than the infantry's trench set. These sets were capable of extreme selectivity with regard to wavelengths and therefore much less prone to being jammed under normal conditions.[142] In addition their greater range and less conspicuous aerials made them ideal for forward work. The extent to which wireless was used by the artillery at Amiens in shown in the table below.

Table 2.2: The use of wireless with the artillery

|

Division - Brigade |

|

|

12 Division[143] |

Yes |

|

18 Division |

Yes |

|

58 Division |

Yes |

|

1 Canadian[144] |

Very successful |

|

2 Canadian[145] |

Not Required |

|

3 Canadian[146] |

Issued but no report |

|

4 Canadian[147] |

11th Onwards |

|

5 Canadian[148] |

Not Required |

|

1 Australian[149] |

CW Sets not received until 17 August |

|

2 Australian[150] |

Sole method until lines laid (Jammed) |

|

3 Australian[151] |

Issued but no report |

|

4 Australian[152] |

Yes (Jammed) |

|

5 Australian[153] |

No sets issued |

As with the infantry wireless use, little information is known about III Corps artillery other than the narrative previously cited.[154] As a general observation, apart from 18 Division, the detail available in the Dominion war diaries far exceeds that contained in the Imperial diaries with respect to Amiens.

According to Fourth Army's GOC Royal Artillery, Major-General C.E.D Budworth:

The depth of the advance on August 8th made the upkeep of communication by telephone a matter of great difficulty, and reliance was placed chiefly on visual signalling and CW wireless sets.[155]

This statement does not agree with the information compiled in 'Table 2.2' above, which concludes that the majority of communications on 8 August were performed by line. Budworth goes on to say that CW was used with success on Canadian and Australian Corps fronts; by implication it is assumed that CW was not used with success on III Corps front.[156] CW sets were issued to British artillery brigades, although evidence from the Australian Corps seems to indicate that they were not treated with the same care as that afforded by the Dominion formations.[157] It also appears that the Canadians had the highest density of sets as confirmed by the CW wireless report of 4 Canadian Divisional Artillery, which concludes by saying 'none of the RFA or AFA Brigades which have been under our control have been equipped with CW wireless'.[158] As there is evidence that CW wireless sets were not issued to some AFA divisional units, the conclusion is that Budworth's statement about the successful use of CW by Australians and Canadians is correct but that the Canadians made greater use of it.[159] However, this is not to say that every Canadian artillery brigade was issued with a CW set, just that the Canadians seem to have been better equipped in this regard.[160] What tended to happen at Amiens was that field artillery units were pushed forward with the attacking infantry and took their orders from the GOC infantry brigade, which reduced their reliance on all intercommunications including CW.[161] A side effect of this was that some CW sets were jammed by the infantry's spark sets such as those of 2 Australian Division and 4 Australian Division.[162] Probably the biggest complaint about CW sets though concerned their weight. The combined weight of a CW set, including batteries and aerials was 200 pounds and this required a party of six men to carry over rough ground.[163] As a result it was recommended that in future operations gun limbers were commandeered with the resultant shock and vibration being taken up by an old mattress.[164]

In addition to field artillery, wireless was in use with the Corps Heavy Artillery units although the only information available comes from the Canadian Corps. Between 8 and 19 August 573 messages were sent containing 20,000 words which contained 'a great deal of valuable information'.[165] These messages were sent to the Canadian Corps Heavy Artillery (CCHA) headquarters by the Canadian Corps Survey section. The Canadian Corps was unique in that, in a similar way to an army, it had its own flash spotters integrated into the intelligence observation and topographical functions. This survey unit was organised to make use of CW sets for flash spotting, wireless taking the place of line, using three forward stations, which doubled up as artillery observation posts.[166] At Amiens these forward stations only performed an observation role and were pushed forward as early as one hour after zero on 8 August. In contrast, their army survey company counter parts did not get forward until 13 August.[167] During the next few days 90 per cent of all information received by the CCHA came from these posts via CW wireless, according to the sections war diary, and 'much valuable information was obtained'.[168] In addition, the diary states that the heavy artillery supplied 80 per cent of all information received at Canadian Corps headquarters.[169] This is not the case as can be seen from the Canadian Corps wireless message summary below.

Table 2.3: Canadian Corps Wireless Message Summary[170]

|

Date |

Corps HQ Sent |

Corps H HQ Rec'vd |

CCHA Sent |

CCHA Rec'vd |

Canadian Ind. Force. Sent |

Canadian Ind. Force. Rec'vd |

Liaison Force Handled |

Total |

|

8 Aug |

30 |

35 |

5 |

12 |

42 |

8 |

132 |

|

|

9 Aug |

50 |

52 |

4 |

10 |

47 |

9 |

172 |

|

|

10 Aug |

37 |

70 |

3 |

20 |

14 |

2 |

146 |

|

|

11 Aug |

36 |

121 |

5 |

40 |

4 |

208 (206) |

||

|

12 Aug |

35 |

91 |

6 |

32 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

177 |

|

13 Aug |

10 |

43 |

5 |

45 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

113 (115) |

|

14 Aug |

8 |

37 |

10 |

45 |

6 |

3 |

1 |

110 |

|

15 Aug |

2 |

36 |

11 |

34 |

9 |

5 |

97 |

|

|

16 Aug |

4 |

32 |

8 |

19 |

2 |

65 |

||

|

17 Aug |

15 |

23 |

12 |

26 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

89 (84) |

|

18 Aug |

10 |

22 |

13 |

10 |

7 |

2 |

2 |

66 |

|

19 Aug |

7 |

16 |

9 |

14 |

46 |

One other unique feature of the Canadian Corps used at Amiens was their use of a motorised machine gun brigade, also known as the 'Canadian Independent Force'. This was a force of approximately 40 armoured lorries established by Brigadier Raymond Brutinel to act as armoured cavalry.[171] The other unique aspect to this force was that the headquarters vehicle contained a CW wireless set that handled over 120 messages in the first three days of the battle.[172] This set was connected to the Canadian Corps wireless section and 'was invaluable, facilitating the quick forwarding of reports to Canadian Corps headquarters'.[173] From a signals perspective, this force stands in stark contrast to the other armoured car formation operating during the battle, namely the 17 Armoured Car Battalion attached to 5 Australian Division. This mobile force did not use wireless, instead relying on despatch rider and pigeons; a total of 29 messages being sent by these means.[174] It is interesting to compare delivery times of messages sent by these two units. The first, sent by the CIF at 10.25 a.m. by wireless was logged as arriving at the Canadian Corps at 12.52 p.m., which gives a delivery time of 2 hours and 27 minutes.[175] The second, sent by the 17 Armoured Car Battalion by pigeon at 11.10 a.m. was not logged at the Canadian Corps until 2.39 p.m., which gives a delivery time of 3 hours and 29 minutes.[176] Both messages seem to have taken an extraordinarily long time to arrive but they are in proportion to messages sent by identical means later in the month, which took 40 minutes, by wireless and 55 minutes by pigeon.[177] Despite this, the 5 Australian Division after action report suggests that this use of slower signalling methods did not adversely effect the combat performance of 17 Armoured Car Battalion.[178]

In addition to the 17 Armoured Car Battalion the Tank Corps had four tracked fighting tank brigades committed during the battle and these were each equipped with 10 wireless sets.[179] A summary of the communications used by these brigades in shown in the table below.

Table 2.4: Signalling methods used by the tank brigades

|

2 Tank Brigade[180] (III Corps) |

3 Tank Brigade[181] (Cavalry) |

4 Tank Brigade[182] (Canadian Corps) |

5 Tank Brigade[183] (Australian Corps) |

|

|

Main Signal Method |

Runners. Although wireless used briefly. |

Mounted Orderlies. Although wireless was used. |

Wireless until 10 August then wireless and lines. |

Wireless until 12.30 p.m. on 8 August, thereafter wireless and lines. |

The operations report for the 5th Tank Brigade contradicts itself with respect to the timing of lines being laid to brigade headquarters and reports two different times namely 10.00 a.m. and 12.30 p.m. The latter has been used in the above table as it is corroborated in the war diary.[184] The 3 Tank Brigade operations report contains an interesting comparison with regards the time taken for the same message, sent to them, by different means, from Advanced Tank Corps headquarters. This message which was sent by wireless, wire and despatch rider, arrived by line 1 hour later than wireless and by despatch rider 1¼ hours later than wireless.[185]

Overall, wireless was a success for the tanks at Amiens as they had realised, in a similar way to the cavalry, that line-based communication was not suitable for an inherently mobile force.

The lack of Imperial division primary sources makes a comparison between the three corps subjective. From a signal personnel perspective the three corps were quite similar, despite the Canadian Corps being the largest corps in the BEF.[186] The divisional signals companies contained between 300 and 400 men of which approximately 16 per cent were wireless personnel.[187] All formations were equipped with a total of approximately 12 wireless sets although these varied by type; CW sets were issued to most but not all artillery brigades.[188] John Moir's view is that the Canadians used wireless to a greater extent:

The Canadian Corps, "often more hospitable to fresh departures in signalling than the Imperial troops", relied upon wireless throughout the advance as an auxiliary system to take surplus traffic. This was a marked exception to the British system, which relied on wireless only when the advance had outrun line communications...[189]

The evidence suggests that this statement is correct. Although the Australian and Canadian Corps used wireless to a similar extent with respect to their artillery and infantry units, the Canadian Corps appear to have used the technology in more diverse ways. This can be seen from their use of CW wireless both with the Canadian Independent Force and the Corps Field Survey Section.

There is a distinct lack of data with which to make a proper assessment of the importance of wireless at Amiens. However, some measurement can be made using the following table in the war diary of the 4 Canadian Division Signal Company.

Table 2.5: Messages Handled by 4 Canadian Signal Company from 8 – 15 August[190]

|

Signal Medium |

Total Messages |

Average per day |

Per cent of total |

|

Telegraph |

2496 |

356 |

44.80% |

|

Despatch Rider Letter Service (DRLS) |

2790 |

398 |

50.07% |

|

Wireless |

250 |

35 |

4.49% |

|

Visual |

36 |

5 |

0.65% |

The recommendation by 4 Canadian Division Signal Company therefore was that communications should be afforded the following order of importance: telephone and telegraph, DRLS, wireless, visual, pigeons.[191] Despite the fact that some units experienced different results, the conclusion is that this order of importance was probably accurate for the majority.

Wireless did receive some glowing reports and was found to be particularly important in filling the communications gap before lines could be laid.[192] However, it was constrained by the limits of the technology of the day in so far as the sets were heavy, fragile and only capable of handling messages in Morse code and then mostly in cipher. This, and the lack of a wireless telephone, meant that it simply was not possible to send the huge volume of messages required solely by wireless means. The use of wireless did come of age though during the battle and according to the Australian Corps had demonstrated that it was now 'successful both as an emergency and normal method of signalling'.[193] The reliance on buried lines was beginning to fade. Perhaps the best indicator of the success of wireless at Amiens is contained in an entry in the Australian Corps Wireless Section war diary that highlights the demand for wireless following the battle as: 'everyone asking for sets'.[194]

Chapter 3

The use of wireless with the Royal Air Force

This chapter will discuss the extent to which aircraft and kite balloons used wireless during the Battle of Amiens. Although 'aircraft' is generally defined as 'any machine supported for flight', in this chapter it will be defined as only those machines with a fixed wing. An attempt will be made to determine how important wireless was to the overall effectiveness of both balloons and aircraft during the battle.

Discussions concerning the fitting of the sterling wireless transmitting set to a balloon basket first began in April 1918 being a product of the mobile warfare experiences of the German March Offensives.[195] However, it was not until 31 May 1918 that the idea gained the formal endorsement of the R.A.F. staff, but with the proviso that its use would be 'rigidly confined' to the sending of zone calls and tactical intelligence information.[196] Operators were strictly forbidden to use wireless for the purposes of artillery ranging for fear of jamming aircraft sets.[197] The zone call system had been designed as part of the switch from destructive to neutralising artillery shoots and used a series of codes to define targets to the guns as follows:

Table 3.1: The wireless zone call system used at Amiens[198]

|

Wireless balloon call |

Description |

|

LL |

Very important target – All batteries that can bear to open fire |

|

GF |

Fleeting opportunity target |

|

NF |

Guns now firing at |

|

FAN |

Infantry |

|

WPNF |

Many batteries active in square (followed by square number) |

|

NT |

Guns NOT firing at |

|

MT |

Motor transport |

A total of 7 balloons were deployed during the battle and were allocated to the corps as follows:

Table 3.2: Kite Balloon deployment to corps[199]

|

Balloon Section |

No 14 |

No 8 |

No 3 |

No 29 |

No 12 |

No 43 |

No 22 |

|

Corps |

III |

III |

Australian |

Australian |

Canadian |

Canadian |

Canadian |

In addition, an eighth balloon, No. 6 section was also allocated but was shelled on the evening of 8 August and did not take part in the battle thereafter. The work of wireless use in balloons at Amiens is confined to the period of semi-mobile warfare from 8 – 11 August and is summarised in 3.3 below. During this period the wireless set was the main method of communication and was carried in the basket while the balloon was moving forward. As soon as the balloon became stationary the set was erected on the ground.[200] One after action report on the battle states that 'this method of sending zone calls by wireless when moving forward worked well and was found to be 'invaluable'.[201]

Table 3.3: Summary of the work done by balloons 8 – 11 August 1918[202]

|

8 August |

9 August |

10 August |

11 August |

Total |

|

|

Successful shoots |

- |

50 |

26 |

25[30] |

101[106] |

|

Hostile batteries neutralised |

- |

19 |

>7 |

9 |

>35 |

|

"Fleeting target" (GF) calls sent |

- |

7 |

>7 |

18 |

>32 |

|

Intelligence passed to corps |

Considerable |

Useful |

Valuable |

Considerable |

Very little work was conducted on the first day of the battle due to poor visibility. Of the shoots performed on 9 August, 96 per cent were from 14 Company working with III Corps. This is not surprising given that III Corps encountered the most resistance during the battle.[203] There is an inconsistency in the report used to generate Table 3.3 in relation to the total number of successful shoots in that three separate figures are given, the highest being 110 and the lowest 101. The figure of 106 successful shoots is probably the most accurate as this has been generated from analysing the detail given in the daily reports. It is difficult to extract out from the report what percentage of the communications were made by wireless, as the information is not complete in this respect. Despite the lack of absolute information the evidence suggests that the majority of information on 9 and 10 August was sent by wireless. This is because the balloon after action narrative states that during these dates there was a period of almost constant movement for the balloons during which wireless was mostly resorted to.[204] Some corroboration of this conclusion is afforded by the fact that all of the 'fleeting target' calls of 10 August and the vast majority of those on 11 August are confirmed as being made by wireless.[205] Further evidence of the extent to which wireless was used by balloons is provided by an Australian Corps Heavy Artillery report which states that, between 11 and 12 August, the balloons sent 40 'neutralising fire' calls to them 'using wireless to a great extent'.[206] This report continued: 'during the advance the balloons were moving forward continually and did exceptionally valuable work'.[207] Most wireless zone calls at Amiens were answered by corps heavy artillery because the majority of field batteries were not equipped with wireless and although the field brigades were so equipped, they were often out of touch with their batteries.[208] The Australian Corps had issued six extra wireless sets for their 18 pounder field batteries but 11 of the 12 artillery brigades kept their sets at brigade headquarters; only 5 Brigade pushed theirs forward with a 4.5" howitzer battery.[209] The work of balloons at Amiens was recognised at the highest level with special praise being given by both Major-General Sir Archibald Montgomery and General Sir Henry Rawlinson.[210] Their views were very similar but perhaps best summarised by Rawlinson:

I have been particularly struck by the vigour with which the balloons were rapidly pushed forward in close support of the firing line and the valuable assistance they rendered to the staff and the artillery...[211]

Despite this praise, the use of spark wireless in intelligence balloons revealed some serious shortcomings during the battle. The main problem was the lack of two-way communication, which was one of the advantages balloons had over aircraft in static trench warfare when the former were permanently connected to a telephone line. A report written soon after the battle complained that intelligence messages 'usually got through to the report centre too late to be of any considerable value'.[212] The report also argued that there had been many cases of potential zone calls being withheld due to uncertainty over target identification.[213] Wireless-telephony was the recommended solution and there had been an opportunity to use this technology at Amiens. On 6 August the Commanding Officer of 5 Balloon Wing, Lt. Colonel Macneese, who had successfully tested the technology in England, wrote to the headquarters of 5 Brigade formally requesting to be given permission to trial wireless-telephony in the coming battle.[214] Judging by the wording of the request it is likely that Macneese was turned down due to previous concerns over the potential problems associated with conducting experiments in battle. In any event, it is unlikely that this technology in balloons would have made a major difference to the outcome of the battle. Mike Bullock and Laurence Lyons disagree with this view and opine that wireless-telephony would have allowed the advance to keep moving forward by calling instant fire down on centres of resistance.[215] However, this opinion ignores the fact that by 12 August the impetus of the advance had diminished significantly which allowed the German line to stabilise.[216] This was partly due to difficulties in bringing guns and ammunition forward and that the advance had come up against the wilderness of the old Somme battlefields.[217] By this point, balloons were once again enjoying two-way communication through fixed telephone lines and no advantage would have been gained by wireless-telephony. Also, the additional batteries that might have been neutralised due to wireless-telephony during the first four days of the battle would have been insignificant when compared to the loss of 92 per cent of the original fighting tank force in the same period.[218]

Wireless-telephony trials had also taken place in aircraft during the summer months of 1918 in an attempt to provide two-way communications with tanks. On 1 July, No.8 squadron R.A.F was attached to the tank corps in order to conduct experiments with a view to finding the most efficient signalling method to facilitate co-operation between aircraft and tanks.[219] The wireless-telephony trials were given up as a failure at the end of July but wireless telegraphy proved to be very successful. On 31 July an aircraft was able to direct a tank over a circuitous two-mile route from a distance of 9,000 yards and at a height of 2,500 feet indicating to the tank the position of anti-tank guns.[220] Once again though there was not enough time to convert this experiment into a practicable battlefield system at Amiens. This is unfortunate because anti-tank guns represented the biggest danger to tanks during the battle.[221] By way of example, the 2 Tank Battalion lost 50 per cent of its 46 tanks to these field guns on 8 August and 62 per cent of its 16 tanks on 9 August.[222] One after action report believed that without hostile anti-tank guns the attack would have been irresistible.[223] However, it is doubtful whether two-way wireless communication between tanks and aircraft would have made a great deal of difference to the number of tank casualties during the battle for two reasons. Firstly, the tanks would have still been extremely vulnerable to fire due to their slow forward speed and secondly, there was very poor visibility on 8 August, in particular, which made these positions hard to see as recorded by an after action report:

Very few anti-tank guns were located and a great deal of practice is evidently necessary before this can be done with success. In one of the cases in which a gun was seen, it was almost surrounded by our infantry, and no offensive action could be taken.[224]

Interestingly, the solution to this problem, as proposed by the Tank Corps, was the formation of an air unit dedicated to tank protection; no mention was made of improved communications let alone wireless.[225]

According to John Slessor: 'the effectiveness of the R.A.F to the Battle of Amiens ceased after 14.00 on 8 August'.[226] This statement completely disregards the work that was done by aircraft in relation to their co-operation with artillery. Historians have tended to neglect this less glamorous side of R.A.F. operations at Amiens in favour of the failed attempts to bomb the bridges over the River Somme.[227] This is despite the fact that it was officially acknowledged that, during the battle, the co-operation of aircraft with artillery, cavalry, infantry and tanks was 'of equal or greater importance than direct offensive action of aircraft'.[228] Peter Mead perhaps holds a clue to this lack of recognition as he wrote:

It would be interesting to know what the 'artillery machines' did...unfortunately we can obtain no information on these matters, either from air force or artillery historians or from surviving records.[229]

It is not known whether this statement was correct in 1983 when Mead wrote his book but the information is available today as shown in the table below:

Table 3.4: Summary of work done by artillery aircraft[230]

|

8 August |

9 August |

10 August |

11 August |

Total |

|

|

Zone Calls sent down |

68 |

34 |

58 |

56 |

216 |

|

Hostile batteries neutralised |

8 |

3 |

7 |

5 |

23 |

All of these zone calls were made using wireless, this co-operation work with the artillery represented the greatest use of wireless by the R.A.F.[231] In addition to its use with the artillery machines, wireless was also used by aircraft specifically tasked to look out for German counter attacks.[232] Little information is available concerning the contribution made by these counter attack patrols other than on one occasion when a counter attack on the cavalry was 'successfully dealt with' by a wireless S.O.S call, which was sent down to a Royal Horse Artillery battery.[233] This was most probably 'K' battery that was fighting alongside the 17 Lancers on 8 August.[234] Several prisoners and one anti tank gun resulted from this action.[235]

Finally, at this stage of the war the R.A.F. was using wireless compass stations on each army front to locate enemy artillery machines that were using wireless to communicate with their artillery batteries.[236] When located, the position of the enemy machines was telephoned to the Army Wing who dispatched a fighter aircraft to intercept and bring them down. The skilled operators at the compass stations were able to recognise individual enemy observers by their unique Morse-key signatures and as a result it was possible to piece together an aerial order of battle.[237] Also, in many cases these compass stations were able to associate the enemy aircraft with a particular battery and this 'shelling connection' was then reported to the CBSO who used it as part of his counter battery operations.[238] This indirect counter battery work was very effective but there is only circumstantial evidence available to show that it was used on Fourth Army front at Amiens.[239] On 17 June 1918 replies were received from a questionnaire sent out to all R.A.F. brigades about the utility of the compass stations; the reply from 5 Brigade, who were operating on the front of Fourth Army, stated 'not used on present front'.[240] However, on 9 September, in response to a suggestion from 2 Brigade R.A.F. that these compass stations should be manned by 'miscellaneous labourers' due to a shortage in personnel, 5 Brigade replied:

...I agree that these stations are of great value, and am of [the] opinion that the method proposed for manning them might be adopted with advantage.[241]

This is not proof that 5 Brigade had been using the compass stations; it may just be that Brigadier-General Charlton was simply aware of their effectiveness on other fronts. The conclusion though is that their use at Amiens was likely, as these stations used established technology that was relatively easy to install and given the importance attached to the battle it seems improbable that they would have been overlooked given the detailed planning. Haig was certainly impressed with the planning and singled it out for special praise in his penultimate despatch:

...the preparations for the battle, including detailed artillery arrangements of an admirable nature, were carried out with a thoroughness and completeness which left nothing to chance.[242]

In summary, both balloons and aircraft used wireless effectively during the Battle of Amiens, with a combined total of around 60 German batteries being neutralised in the first four days. Assuming six guns per battery this represents 68 per cent of the total number of guns identified prior to the battle.[243] Although this figure is not as impressive as the 95 per cent neutralised in the initial counter battery operation it still represents a significant contribution to the battle. A large number of fleeting targets were also identified and engaged and valuable intelligence sent to Corps. As a result, Corps commanders were often better informed than their subordinate divisional commanders who were physically closer to the action.[244] Official notes made after the battle believed these artillery patrols were of 'extreme importance' and that calls from the air were 'certainly the quickest and often the only means of discovering the enemy's new artillery positions'.[245] Although wireless telegraphy between aircraft and tanks as well as wireless-telephony between balloons and corps headquarters had both been trialled successfully, it was decided not to use them in the battle. This was probably the correct decision as their use came with an element of risk and the results they would have achieved were unlikely to have made a significant impact. Finally, some measure of the importance attached to air to ground wireless operations during the Battle of Amiens can be gained from the fact that in two cases, ground stations were kept in action by the R.A.F. dropping new sets to them via parachute.[246]

Conclusion

The success achieved by the BEF at the Battle of Amiens depended to a great extent on the attack being a complete surprise. To bring about this surprise the preparations for the battle included three schemes designed around secrecy and deception all of which involved wireless. The primary objective was to camouflage the movement of the Canadian Corps southwards from Arras to Amiens by deceiving the German Army into believing that an attack was imminent either on the First Army front at Arras, or on the Second Army front at Kemmel. The presence of the Canadian wireless station inserted opposite Kemmel was detected, as was the presence of the two Canadian infantry battalions. Despite this, the German Army staff did not update their situation maps to reflect a move of the Canadian Corps to Kemmel, even though they realised that two Canadian divisions had been replaced on First Army front on 4 August. The German Official History makes no mention of the two Canadian casualty clearing stations or the tank wireless sets that were also operating near Kemmel and it is therefore assumed that these were either not detected or were ignored. The wireless call sign changes that had taken place in June and July did make the BEF's wireless signals more secure and this disrupted the German Army's ability to identify the movement of the Canadian and reserve divisions to Fourth Army. Although the wireless silence days were thought to mislead the enemy they also aroused suspicion and better results would probably have been obtained by keeping wireless traffic at normal levels. Ultimately these wireless measures did not deceive, they did however contribute to a state of confusion in the German Army, and as a result the movement of the Canadian Corps from Arras to Amiens was not detected. This was the decisive factor at Amiens.

Analysis of the use of wireless with the ground forces reveals that the further a formation was down the chain of command, the more difficult wireless communications became. The greatest use of wireless with the infantry was between corps and division with very little use forward of battalion. Wireless was particularly useful during the period between moving a headquarters forward and lines being laid. The paucity of information in the British divisional diaries makes it difficult to reach a definitive conclusion with respect to their use of wireless. The implication from the war diary of 18 Division though is that wireless was not liked and little used, due mainly to problems with enciphering and deciphering messages. The Dominion infantry divisions, as well as the Cavalry made better use of wireless and learnt that in mobile warfare messages should be sent in clear. The use of wireless by the field artillery brigades was mixed but it is the Dominion divisions that used it more effectively. The CW sets used by the artillery required six men to carry and lack of suitable transportation was the biggest complaint together with 'friendly jamming'. The Canadian Corps made good use of wireless with the armoured cars of the Canadian Independent Force as well as the corps Survey Section who between them handled over 200 wireless messages from 8 – 11 August. According to Peter Simkins, the Canadian Corps were the most effective in combat, this dissertation concludes that they also used wireless to the greatest degree but it is difficult to establish a definite link between the two other than the latter enabled a more coordinated weapons system. Similarly, there is no evidence that the use of wireless by the armoured cars made them more effective in the battle. The tanks used wireless extensively, particularly 4 and 5 Brigades with the Dominions. In summary, the evidence suggests that the Dominion divisions did use wireless more extensively than the British divisions, particularly the Canadians. Wireless was successful as both an emergency and normal method of signalling but was the third most important communications method; line was still the mainstay during the advance.

The kite balloons made significant use of wireless, especially when moving forward. The seven balloons used were responsible for over 100 successful artillery shoots, the majority of which were made using wireless. In addition over 30 fleeting targets were engaged and valuable intelligence information passed back to corps. Most of the wireless calls were answered by the corps heavy artillery as the field batteries were mostly not equipped with wireless and were often out of touch with their brigades. A request for wireless-telephony to be used in balloons during the battle was denied. However, it is unlikely that this system would have made a significant impact to the battle. Trials of wireless-telephony between tanks and aircraft proved unsuccessful in July and although good results were obtained using wireless telegraphy it was too late to integrate this into the battle. In any event pilots were not specially trained to locate anti-tank guns and bad weather hampered visibility on the first day of the battle so it is doubtful that this would have been of benefit. Artillery aircraft equipped with wireless sent down over 200 zone calls, which resulted in 23 German batteries being neutralised. In total balloons and aircraft accounted for 68 per cent of the total number of hostile guns identified prior to the battle. It is more difficult to quantify the work of the counter attack aircraft equipped with wireless but there is at least one example of their successful work, which involved the cavalry. The work of direction-finding compass stations at Amiens is largely unknown although the conclusion is that they were used to keep hostile aircraft from overflying the British lines.

In summary wireless was used extensively at Amiens and proved to be extremely useful, especially to the Dominion corps and the R.A.F. Problems with weight, jamming and the enciphering and deciphering of messages meant that line was still the main communications method for ground forces at Amiens. The conclusion is that wireless was useful but not essential.

Bibliography

Only works cited have been included in this bibliography.

- Archival Sources

1.1 The National Archives (TNA), London

- ADM 137/4700 Intelligence Branch GHQ, 1 January1918 – 31 December 1918.

- AIR 1/109/15/27 Summary of Wireless Telegraphy in the R.A.F. from the Outbreak of the War, 1 January 1918 – 31 December 1918.

- AIR 1/677/21/13/1887 J. Nerney, The Western Front Air Operations May 1918 – November 1918.

- AIR 1/725/97/1 Wireless Telephony in the R.A.F., 1 January 1917 – 31 December 1918.

- AIR 1/725/97/2 Artillery Observation by the R.A.F., 1 June 1918 – 31 December 1918.

- AIR 1/725/97/6 Notes on General Development and Work of R.A.F in France, 1 July 1916 to 30 September 1918.

- AIR 1/994/204/5/1222 Development of Kite Balloon Observation, 1 October 1917 – 31 March 1918.

- AIR 1/996/204/5/1234 Reports and Instruction on Wireless Interception Scheme, 1 March 1918 - 30 September 1918.

- AIR 1/1074/204/5/1659 Signalling: Co-operation Between Aircraft and Infantry, 1 August 1918 – 28 February 1919.

- AIR 1/2078/204/444/6 Use of wireless in balloons, 1 August 1918 – 31 March 1919.

- AIR 1/2218/209/40/1 5 Brigade R.A.F War Diary, 1 August 1918 – 31 August 1918.

- WO 95/20 GHQ General Staff War Diary, 1 June 1918 – 31 July 1918.

- WO 95/21 GHQ General Staff War Diary, 1 August 1918 – 30 September 1918.