Major 'Alastair' Soutar, M.C.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Major 'Alastair' Soutar, M.C.

One of the well known 'classic' accounts of the First World War is 'Twelve Days' published in 1933 (and more recently republished as 'Twelve Days on the Somme') by Sidney Rogerson, an officer on the staff of 23 Infantry Brigade (part of the 8th Division). Less well known is his second book, about his experiences in May 1918 on the Aisne. This account 'The Last of the Ebb' is a superb story of the German attack on the Chemin des Dames sector and the British retreat over a number of ridges and valleys south of the River Aisne.

Above: Captain Sidney Rogerson and his book

Some years ago my wife and I followed Sidney Rogerson's book, trying to drive in his footsteps and look at the various actions he describes on the retreat. Tracking Rogerson's account southwards from the front line that was overwhelmed on 27 May 1918, we headed to Jonchery-sur-Vesle where we gravitated to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery. We took some time to walk along the headstones which - according to the cemetery register - number 367. Whilst most of the headstones are 'unknown', the remainder (exactly 100 as it turned out) are identified by name, unit and date of death.

The majority of the dates show the identified fatalities were victims of the German 1918 attack on the Chemin des Dames (now known as The Third Battle of the Aisne) and the subsequent fighting withdrawal. The headstones cover other dates, but 64 of the identified headstones are for men who were in the four British Divisions that were unfortunate enough to be in the path of the German breakthrough attempt on 27 May. Sidney Rogerson's 8th Division is represented with 22 burials, but the 50th (Northumbrian) Division fatalities who are identified number just four men. Officers and men from the other Divisions that were so badly caught up in the battle are represented, with the 25th Division having 26 identified officers and men and the 21st Division a further 12 identified burials.

Above: The headstone of the 'unknown Major, Royal Engineers' at Jonchery-sur-Vesle British Cemetery

All this was of course not immediately obvious as we picked our way among the headstones. What was striking was the surprising discovery of an orderly from the Friends Ambulance Unit and a sole Canadian officer who was with the RAF. However, what really caught our eye was the headstone dedicated to an unknown Major, Royal Engineers 'Known Unto God'. Obviously this officer had been partly identified when buried here, but was there any way his unit could be identified? There were no other Royal Engineer burials that we could see in the cemetery and soldiers in adjacent graves were generally also 'unknown'.

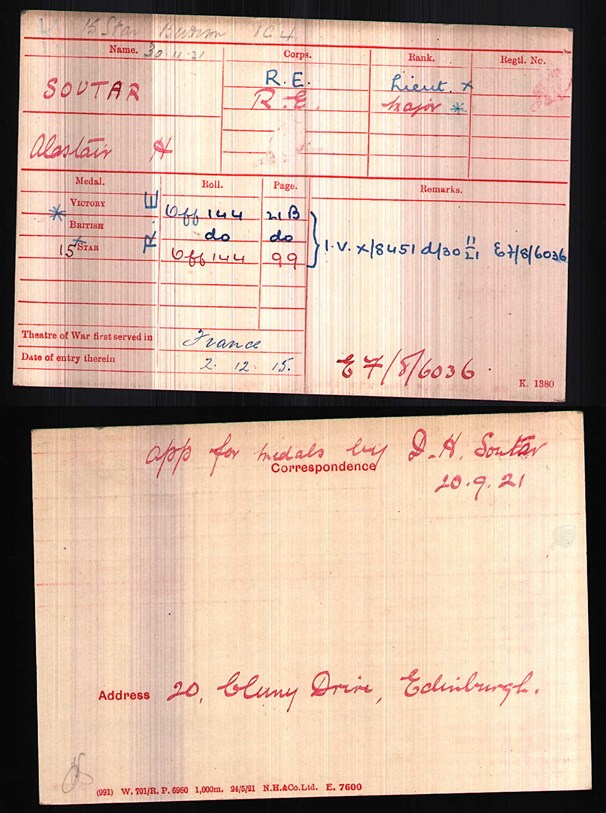

On returning home a quick search of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) database proved illuminating. Knowing that the British were only in this area in 1918 for a short period, how many Royal Engineers were killed in France at the end of May and early June 1918? Actually quite a lot, it turned out; more than 70 of these having no known grave and were therefore commemorated on the nearby Soissons Memorial to the Missing. However, only two held the rank of Major, and one of these was buried near Boulogne. The other - Major Alexander Henderson Soutar, MC - had been killed on 28 May 1918 and was commemorated on the Soissons Memorial. This was promising, his unit was known (98th Field Company) and this had formed part of the 21st Division. The CWGC entry told me his parents, at least immediately after the war, had lived in Edinburgh at 20 Cluny Drive. To make sure this was the only candidate, I tackled the CWGC another way: how many Royal Engineers with the rank of Major were killed in the war and commemorated in France? This was another surprisingly large number - over 60. But only ten of these were commemorated on memorials to the missing. Once again, the same name cropped up: Major Soutar. Surely this was the 'unknown Major', but I really needed more proof.

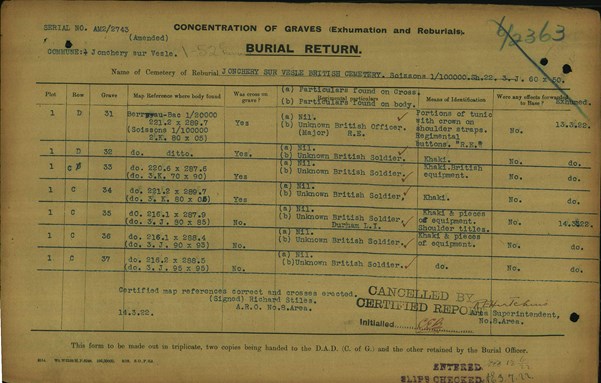

Fortunately it was possible to see from the CWGC web site the original paperwork relating to the 'unknown' Major's burial. This showed that the body had been exhumed on 13 March 1922 from (map reference) 221.2 x 289.7.

The Burial return on the CWGC web site which detailed the original place of burial of the 'unknown Major'

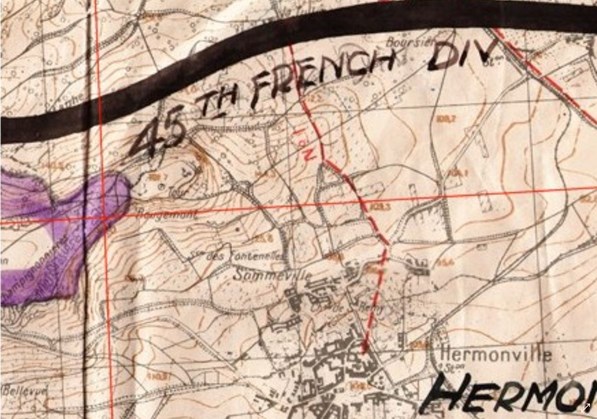

An additional difficulty now arose. Because the area was well away from the normal operations of the British Army (it was really a French sector), the usual trench maps were not easy to come by. A quick email to WFA member Howard Anderson proved helpful. He sent me a copy of a map covering the area and this showed the map reference was not far away from Jonchery, it was near a village called Hermonville.

The map showing the map reference for the original place of burial. 221.2 x 289.7 intersects north west of the village on a steeply sloping hill-side. Note the word 'Champignonnieres'

The question arose, was it possible to put Major Soutar (the 'obvious' candidate) and his unit (the 98th Field Company) at Hermonville? What was needed was the war diary of the 98th Field Company, Royal Engineers. This again proved fruitful. It was fairly straight forward to establish that the 98th Field Company had been at Hermonville on 27 May. The diary entry even referred to Major Soutar and - something that puzzled me - mentioned the company taking up a position at "Champignonnieres". I could not immediately see this as a place, and tried google to translate this word. It suggested something to do with mushroom beds. I went back to the map once again and noticed the word written diagonally adjoining the "intersection" point of the map reference. At that point I knew that I would have as much proof as was needed to make a case to the CWGC.

A slight complication now arose in that the Medal Index Card of this officer detailed his name as "Alastair H. Soutar".

The Medal Index Card of Alastair H. Soutar

This I assumed was simply a clerical error in the 1920's, but the address on the reverse of the card was identical to the one detailed on the CWGC's web site (20 Cluny Drive, Edinburgh). From Google 'street view' I could see this address is clearly an imposing Victorian-era property.

Cluny Drive, Edinburgh

All that remained was to look at Major Soutar's file at The National Archives, so I arranged to make the journey down to London. I took a copy of all the contents of his file which provided further details, including a letter (from a Lieutenant Godson) recounting how Major Soutar was killed. It was now time to put the case to the CWGC who, I knew, if they agreed with my analysis, would pass the case to the Ministry of Defence (MOD).

Earlier this year (2018) Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC), part of the MOD which confirms the identities of those found and traces surviving relatives, agreed that the unknown Major was indeed Alexander Soutar and that his grave at Jonchery would be given the honour of a named headstone.

So what was his story? Here's what we know.

Alexander ('Alastair') Soutar, Royal Engineers

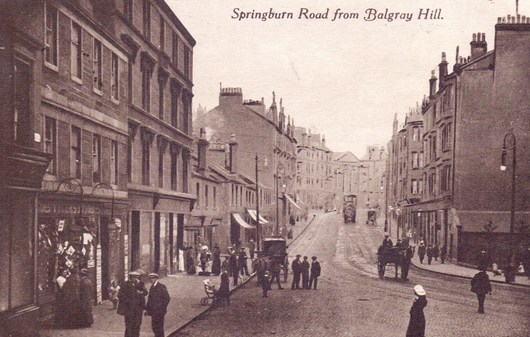

On 23 July 1887, the Rev Alexander (36) and Mary Soutar (25) had their first child. They were living at the time in the village of Cullen, Banffshire in the north East of Scotland. The child, a boy, was named Alexander after his father. Within a year the family moved to Glasgow, where Rev Alexander was to take up an appointment as a minister in the Springburn Free Church in the city.

Springburn Road Glasgow from Balgray Hill (1916)

We don't know anything about Alastair (as this was how the young Alexander was known by his family, the article will now refer to him as such) in this period other than he attended Whitehill School in Glasgow. This was about two miles away from the Springburn area. The assumption is that he was clever and possibly had an aptitude for engineering.

Whitehill School, in the 1970's prior to demolition

In 1899 the family moved to Thurso on the north coast of Scotland, just 20 miles west of John o'Groats . The 1901 census lists them at Princes Street in Thurso, with the parents (Alexander and Mary) living with Alastair (now aged 13), Frank (12), Constance (9), David (6) and Dorothy (7 months). The household also comprised two others who were probably servants. Another son (William) was born in 1902. Alexander was obviously a pillar of the local community, being a minister in the First United Free Church in Thurso.

The First United Free Church in Thurso still stands, although no longer used as a church.

The war came along in 1914. At the outbreak of the conflict Alastair had just celebrated his 27th birthday. Again, we know nothing of his enlistment other than a torn piece of paper within his file at The National Archives which is undated. This says he was appointed as a temporary 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers. His application to a temporary commission initially gave his address as Castlegreen, Thurso (probably the family home) but is amended to 12 Norse Road, Scotstoun, Glasgow. The assumption may be that he was working in the city at the outbreak of war. It seems he was medically examined and passed fit for a commission on 22 December 1914, and would have soon commenced training.

Norse Road, Scotstoun, Glasgow

He was probably promoted to Lieutenant whilst in the UK and at some stage was ordered to join the 123rd Field Company Royal Engineers, which became part of the 38th (Welsh) Division. This company, together with the 124th Field Company was formed from 650 skilled craftsmen who had originally volunteered to serve as infantrymen. A third Field Company for the division (numbered 151) was formed out of the surplus men from the other two companies. Overcoming the Welsh accents of his men would have been at the easier end of the scale of the problems that he faced. These units raised from the flood of 'Kitchener Volunteers' were short of almost every form of supply, and had to prepare for war as quickly as possible, with very few pre-war regular Officers or NCOs to assist.

The divisional headquarters of the 38th (Welsh) Division formed at Colwyn Bay, with its constituent units scattered over north Wales. Warned to be ready for France in November 1915, the division was inspected at Crawley Down on 29 November by HM Queen Mary, with her daughter HRH Princess Mary.

The division began to leave Winchester for the crossing to France on 1 December, and the 123rd Field Company's War Diary reports how they sailed on board the SS City of Chester from Southampton at 5pm that day "Weather: rained practically all day".

The war diary of the 123rd Field Company makes a number of references to Alastair over the coming months. The first (calling him Lt Souter - being a misspelling of his name) comes on 27 December 1915 when we learn that Alastair started the instruction of infantry of the 114th Brigade in Field Engineering at Le Sart near Merville, close to the Belgian border.

In the new year of 1916, tragedy struck when Alastair's younger brother, Frank, was killed. He was serving in Mesopotamia with the 2nd Black Watch.

By 12 January Alastair was commanding number 2 section of the company in the line from 'Farm Corner to Copse Street'. This was adjacent to the front line village of Richebourg-l'Avoué. Coincidentally, a nearby trench was named Blackadder (alternatively Black Adder) after Charles Blackader, who had commanded a brigade of Indian infantry in the area some months earlier. Blackader was to be appointed the commander of the 38th (Welsh) Division within six months.

Brigadier-General (later Major-General) Charles Blackader at his headquarters 24 July 1915

Alastair was granted home leave on 24 May 1916, commencing the long trip to Scotland. He returned to the 123rd Field Company on 4 June.

Men of 123 Field Company, Royal Engineers. Courtesy of the BBC

The Somme

The division was sent to the south to take part in the Battle of the Somme. The action at Mametz Wood is well known, and was a disaster for the whole division. Although not infantry, the field companies of Royal Engineers were involved in the action and the company's war diary gives some detail about what they were doing.

A company parade at 1.30am on 10 July revealed the strength of the unit to be 6 officers and 139 other ranks. By 6am two sections were ordered forward to Queen's Nullah, and were instructed to wire the newly taken trenches (ie prepare defensive barbed wire entanglements). By 11am number 2 and 3 sections were ordered forward to relieve the men who had started the work. It can be assumed that Alastair was still in charge of number 2 section and that he was therefore involved in this work. The wiring was completed at 3pm, and the men were ordered to remain in Mametz Wood to be held in reserve. The British troops in the wood were heavily shelled during the course of the day and by nightfall the engineers were ordered to the south edge of the wood and to remain in reserve there.

During the 11th strong points were constructed within the wood, this was completed by early afternoon. Company casualties were remarkably light, with three men killed, and a further man who died of his wounds. (The three killed outright have no known graves and are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial). One officer and 23 men were wounded. Unusually these men are named, and include Lt Soutar. One of the 'other ranks' to be wounded was "R Bell". He will return to the story later.

The War Diary of 123 Field Company Royal Engineers detailing Lt AH Soutar being wounded on 11 July 1916

Mametz Wood with the famous memorial in the foreground.

The 38th (Welsh) Division was badly damaged by its involvement in the fighting at Mametz, losing up to a fifth of its strength during the five days fighting in and around the wood. The divisional commander was sent home and replaced by Major-General Charles Blackader. Because of its heavy casualties, the division was withdrawn from the battle in order to absorb reinforcements.

No further reference is made of Alastair's injury in the 123rd Field Company's War Diary. It is likely that the wound was not serious and Alastair is mentioned again in the war diary a month later when he and nine men were detailed to complete some work on some 'ammunition sheds' in the Caestre / Abeele area (on the French-Belgian border).

It appears that Alastair was allowed home on leave over Christmas 1916 and New Year 1917, it is noted he rejoined the company on 2 January 1917 from leave.

In April, Alastair is again noted in the war diary as commanding number 2 section at a strong point called Turco Farm. He was either improving the dugouts here, or working on the front line trench. Other commanders of sections were Lt Dickinson, who was also at Turco Farm, Lt Evans who was on the canal bank (at Ypres) and Lt Wynell Lloyd, who was commanding the 4th section.

On 1 May, Alastair was, with his number 2 section, on the Canal Bank at Ypres. The actual nature of the work is not detailed, but it is likely to have involved improvements to dugouts and trenches in the area, some of which (the 'Yorkshire Trench') are preserved to this day.

On the 14 June there is another reference to Alastair who, with his section, was working on a communication trench at Szwaanhof Farm, with Lt Lloyd's 4th section in the front line. Although it may not have been formally communicated to the men, all this work was important as the Third Battle of Ypres was about to start, and the 38th (Welsh) Division was once more going to be in the thick of the fighting.

1st July 1917 finds another reference to Alastair, whose number 2 section was making 'Moat Trench' at Szwaanhof Farm, constructing dugouts in 'Welsh Harp' and working on a tunnel near the canal bank. This was not risk-free work. Alastair was slightly wounded on 19 July, but seems likely to have carried on without needing any evacuation for medical treatment.

Passchendaele, Promotion and a new Company

The Third Battle of Ypres commenced on 31 July 1917, the company being ordered forward to consolidate gains made on the day. Two other ranks were killed and three wounded. By now Alastair would have been an experienced and presumably highly regarded officer. Casualties among other companies would have meant there were vacancies to be filled, with promotions available for those chosen. Alastair was selected as a suitable candidate for such a promotion.

On 18 July Alastair said his goodbyes to the 123rd Field Company and joined 124th Field Company (so therefore still part of the 38th Division) as acting Captain and second in command. This would have been a proud moment for both him and his family back home in Scotland. The work of the 38th Division continued in the Ypres salient, and in early September, the 124th Field Company was in the Langemarck sector. There is less detail in their war diary about the type of work undertaken, but occasional casualties are recorded.

A further ten days home leave was granted on 6 September. Although he could not have known it, this was to be his last visit home.

Early December saw Alastair sent on a 'School of instruction' course - this must have been quite an in-depth instruction as he didn't return to his unit until 30th December.

The war diary records him being awarded the Military Cross on 2 January 1918. This was likely to be for his continued work rather than a specific action.

No further reference is made to Alastair until 30 March when he left both the 124th Field Company and the 38th Division to join - as officer commanding - the 98th Field Company (which was part of the 21st Division).

Rather than following Alastair's story at this time, it is necessary to return temporarily to the 123rd Field Company which he had left some eight months earlier. Lt Wynell Lloyd, who may well still have been commanding 4th section, was undertaking an inspection of the men on 17th April when he had cause to speak to Sapper Robert Bell. It seems that Bell was not wearing his puttees, so was told to go and put them on. Instead of obeying the officer, Bell (who it will be recalled had been injured at Mametz Wood) went to his rifle and shot Lloyd dead. Bell was immediately arrested and soon went before a court martial. Found guilty of murder, Bell was executed by firing squad on 22 May.

All of this was in the future and Alastair was not involved with this incident, having been transferred to a different division. He would probably have found out about the death of his former comrade but joining his new command on 3 April 1918 would have kept him busy.

The 21st Division had been heavily involved in the German attacks in late March and had suffered heavy casualties, the 98th Field Company losing seven men killed on 22 March, with the officer commanding the company being last seen rallying his men. It seems that the 21st Division's field companies were so badly mauled at this time that they were forced to merge into one unit for a time, and were acting as infantry to help stem the German advance. Casualties for the month included 21 officers and men wounded and a further 24 missing. It was into this situation that Alastair was promoted to the rank of Major and had to get the company back to something like fighting fitness.

As mentioned, he joined the unit on 3 April but the war diary records scant details of what went on during this month - a single page covering the entire month of April. What is not recorded is the division being involved in heavy fighting during the German 'Georgette' offensive which commenced on 11 April. This fighting took place on the French-Belgian border and many casualties were incurred, particularly among the infantry battalions. Fortunately for the Royal Engineers, there is no record of fatalities in this period for the 98th Field Company.

The Third Battle of the Aisne

The war diary is only a little more detailed for the month of May, but what we do find is the 98th Field Company (along with the rest of the 21st Division) being sent south by train on the 4th May and arriving at Savigny sur Ardre on the 6th.

Savigny sur Ardre

From there the company marched in stages towards Hermonville, and into billets. The plan was for the division to recover from its two exhausting battles in March and April and absorb and train replacements. This was not to be.

Hemonville "from the old windmill" (1913)

Hemonville "from the old windmill" (1913)

On 26 May the war diary of the 98th Field Company mentions a raid by one officer and 12 men from the company on enemy trenches. No casualties were incurred but the following day, news reached the unit of an impending major German offensive. The 21st Division prepared to receive the full force of a German onslaught for the third time that spring.

The fighting on 27 May was brutal. The Germans had refined the art of the surprise artillery bombardment and British positions were (due to a French General's intransigence) badly positioned. The Germans quickly broke through, although dogged rear-guard actions by small parties managed to delay the Germans. Nevertheless the 21st Division was in deep trouble. Troops that were held in reserve were instructed to take up positions and to halt, or at least delay, the German attack. These included the division's pioneer battalion and its Field Companies of Royal Engineers.

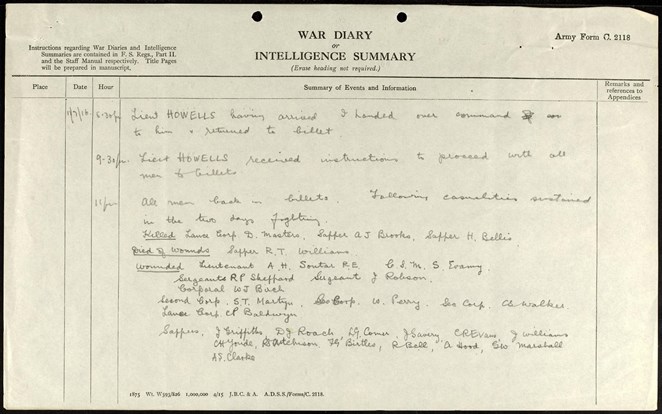

The war diary of the 98th Field Company takes up the story.

27 May: [Portion of] Company and attached infantry manned battle positions north west of Hermonville at 12.45am under heavy gas and High Explosive shelling. Transport moved out of Hermonville to a wood south of Luthernay Farm on the Pévy Road. Company HQ at road to Chateau de St Remy. Lt Womersely MC and 2/Lt Boyd Moss were wounded about 5am and seven other ranks killed and four wounded.

Luthernay Farm

At 6pm the Company was relieved in its battle positions by the French and took up another line at 64 Infantry Brigade HQ at Champignonnieres.

28 May Transport moved at 3am to Branscourt. After bombardment, company was attacked in flank at 8.30am. Bombardment lasted four hours and trench mortars were used by the Germans in addition to guns [meaning artillery]. The company was forced to withdraw without officers leaving Major Soutar MC and 2/Lt Cadell wounded.[1] 2/Lt Moss, the attached infantry officer was killed.[2]

The company war diary for the month records a total of nine men killed, with two officers and 19 other ranks wounded plus two officer and 28 other ranks 'wounded and missing' .[3] It also lists the "attached officers and attached men" (from the infantry who would have been supporting the company) as incurring four casualties (killed and wounded) plus a further 58 "missing".

Whilst many of the missing would have ended up as prisoners of war, this was not to be the case for Major Alastair Soutar and 2/Lt Richard Cadell.

Left: Richard Lewis Cadell as a boy. He was a fellow scot, from Edinburgh.

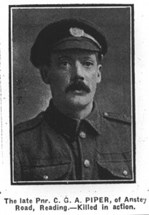

Right: Pioneer Charles Piper, 98th Field Company RE. One of the men killed at Hermonville, he died on 27 May 1918

Lt Godson was one of the officers of the company who seems to have been captured on this day. In late December 1918 it is likely that Richard Cadell's parents were making enquiries about their son and in response to their letter, Godson wrote to both Mr Cadell and Rev Alexander Soutar. A couple of letters from Alastair's file at The National Archives when combined, provide a detailed account of Alastair's last day. (The following is a merger of these two letters.)

On the morning of the 27th [Godson explains] my company was sent to hold 'Brigade Hill' North West of the village of Hermonville. Lt Soutar - then acting Major commanding 98 Field Company RE - occupied a position on my right with the 97th Field Company on my left. On the morning of the 28th about 9am the enemy attacked. I received a message from Maj Soutar to [illegible] reinforcement as he was being hard pressed. Being in a similar position myself I was only able to send him ten [men]. About half an hour later I saw Maj Soutar and the remnants of his company coming down the road.

[At 10 o'clock] Major Soutar joined me with the remnants of his company, and we chose a new position and got the men distributed. In these positions we were able to keep the enemy at bay for some time. About 11.30 [or 12 to 12.30 in the other letter] an NCO came in from the right [or left flank] and told us that we were surrounded (a thing we had known for some time.) The Major and I left Lt Fennell in charge of the right and decided to go out and investigate with two orderlies. Maj Soutar was carrying a rifle and I a revolver. About 300 or 400 yards to the left we met some Boche, and promptly fell on our faces. Major Soutar raised himself to fire with his rifle but received a bullet through the breast, which I think passed through the heart killing him almost instantly. I bent over him to see what was wrong and incidentally in so doing occupied the same position he had just vacated. Several shows were fired at me, one hitting me in the foot cutting the tendon behind the heel. As soon as I was hit, the two orderlies who were in the hollow, each got hold of a leg and pulled me down into the hollow. I was later taken prisoner with Lt Fennell who was unwounded.

I admired [your son] immensely. Everyone did. He was a man all through. If you are ever in London and would care to let me know, I would be only too pleased to meet you as I am sure you would love to see anyone who knew him.

Hermonville Military Cemetery - in the hills behind are the positions more than likely held by Alastair's company and where he was killed on 28 May 1918

It is not known if Rev Alexander Soutar or his wife visited Lt Godson in London. The Soutar family had certainly paid a heavy price in the war, with two sons killed and the third son (David) ending up as a prisoner of war. Neither Alastair or Frank had a known grave, so there was no focus for the family's grief. Rev Soutar died at his home at Cluny Drive in 1939, aged 83. He outlived his wife Mary by a year.

Alastair and Frank were commemorated locally on the Thurso town war memorial and at Whitehill School in Glasgow (where Alastair is listed as 'Alister').

Above - Whitehill School War Memorial. 'Alister' Soutar and his brother Frank are both named

Thurso War Memorial

Hermonville now is a quiet backwater in the 'champagne' area of France. Even among those who visit the battlefields, it is little known. The CWGC cemetery in the village is small and rarely visited, but is well cared for by the CWGC. Most of the men from Alastair's company killed in the defence of the village are buried here, but Alastair was not among them.

The hills to the north west of Hermonville are given over to vineyards. A parascending club use the area for their flights.

For one hundred years, Alastair has been listed on the Soissons Memorial as one of the nearly 4,000 men who were killed in the area and who have no known grave. At last, after all this time, he has an identified grave.

Visitors to the beautifully maintained Jonchery-Sur-Vesle British Cemetery will be able to see the new headstone standing over his grave and - if they read this article - know about his life and service which ended on 28 May 1918.

Jonchery-Sur-Vesle British Cemetery

Article by David Tattersfield, April 2018

Below: A 14-minute video showing footage from the ceremony in which Alastair was - finally - honoured with a 'known' headstone.

NOTES

[1] 2/Lt Frederick Moss mentioned in the war diary, being an officer of the Leicestershire Regiment but attached to the 98th Field Company, has no known grave and is commemorated on the Soissons Memorial. (It is interesting that within Hermonville Cemetery is an unknown Leicestershire Regiment soldier. It is not impossible that this is Lt Moss's grave).

[2] Richard Cadell was originally buried as an unidentified officer, at Hermonville British Cemetery but was subsequently identified.

[3]One officer (Richard Cadell) and eight other from the 98th Field Company were subsequently buried at Hermonville Military Cemetery. Of these, five men of the 98th Field Company were originally recorded as being buried at Hermonville German Cemetery and were commemorated by a special memorial at Hermonville British Cemetery, but this has since been removed and these five men have individual headstones.