Blankety Hell: Ivar Campbell, A Life

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Blankety Hell: Ivar Campbell, A Life

Ivar Campbell was the son of Lord George Campbell and his wife Sybill K.M. Lascelles Alexander, a very wealthy woman in her own right. His Grandfather was the 8th Duke of Argyll and his Uncle Ian the 9th Duke. Ian was married to Princess Louise. When he became Duke in 1900, Ian inherited some financial problems, and as they mainly lived in Kensington Palace carrying out Royal duties, they rented Inverary Castle to George and Sybil until it was required by Duke Niall for his personal use in 1914

Ivar and his sisters Joan and Enid enjoyed life in the castle and at their London Home, 2 Bryanston Square; at other times Dunderave Castle, not far from Inveraray on Loch Fyne, and other large houses in the area.

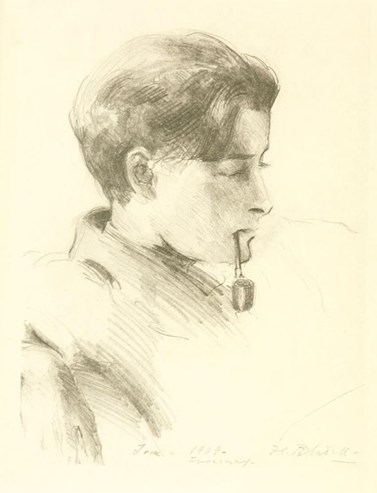

Above: Ivar Campbell

Ivar attended Stone House, a small preparatory school for boys in Broadstairs run by Rev E.D. Stone. He then went to Eton and his education was completed by a year at Christ Church, Oxford in 1908. Here he studied Elizabethan literature, showing the depth of his love for books and writing. Ivar had a passion for being in the open air, and the years he spent in Argyll enjoying the landscape in complete freedom gave inspiration for many of his literary efforts. Walking was another love, and he wrote

“Walking is a brave thing, a large thing, a dusty thing, as you will, but like the sea it touches heaven”

His observations when walking quiet country roads were astute, and noted with some style in letters to family and friends.

“Along a lane near Grafton there are more poppies than are to be found I suppose than any other lane in the English shires. From the field beyond, hidden by a leafy beech hedge whereupon clamber and sway wild roses and over which elderberry trees open to the skies flat flowers that are big platters for the bees to feed upon, they pour down to the white road's edge in a thousand scarlet ranks; and in number they are like a great company of cardinals seated tier upon tier.”

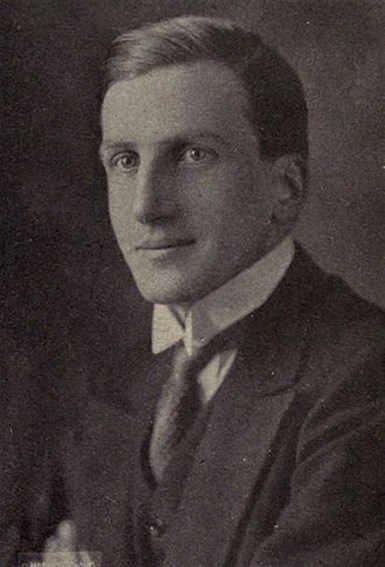

While Ivar had a great many friends, one notable close friend was “Bunty” Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell, a Scottish artist. They were possibly distantly related. An eccentric, witty man, Cadell attended the Royal Scottish Academy and then studied in Paris, coming under the influence of the Impressionists, Whistler and Cezanne. He met another Scottish artist, Samuel Peploe, in Paris and become friends with the more senior artist whose career and art had a distinct influence over him. Bunty visited Inveraray on several occasions and became a close friend of the family, particularly with Lady Sybill, Ivar’s mother. Ivar bought several of his friend’s paintings at Bunty's exhibitions.

Above: Cadell, self portrait. Public Domain

In 1910 Ivar and Bunty made a trip to Venice, Bunty being financed by Sir Patrick Ford, who became one of his most important patrons. The time in Venice was inspirational to Cadell and Ivar, who wrote a poem dedicated to his friend. It was published in Country Life in 1910. While Bunty was known as being homosexual, the friendship appears to have been very close but platonic.

Shortly after their stay in Venice, Ivar introduced Bunty to Iona, closely associated with his grandfather the 8th Duke, and the island had a profound effect on the artist. The light and colours of the beaches and skies were perfect for his work, and attracted several other artists including Peploe.

Above: Iona by Cadell. Public Domain

Like many young men Ivar spent time in Europe; he loved the delights of Venice and found people and things to interest him wherever he ventured. He seemed happy and comfortable anywhere, but particularly loved the Left Bank in Paris, attracted by the artistic life, and he made many friends there. Some of the people he met were American, and talking to them excited a curiosity about the country which was so different from Europe. Whatever long-term plans Ivar had for a career, the opportunity arose near the end of 1912 for him to work in Washington as honorary attaché to the British Embassy.

The appointment may have been influenced by a family connection, or it may have been co-incidental that a cousin also worked as a Secretary at the Washington Embassy. Lord Eustace Sutherland Campbell Percy was the seventh son of Henry Percy, 7th Duke of Northumberland and his wife Lady Edith, daughter of George Campbell the 8th Duke. Edith and Ivar's father were siblings making the men first cousins. Eustace served in the Diplomatic Service from 1911 until 1919 and he became a Member of Parliament in 1922. During the Great War he served successively in the Foreign Office's western, war, and contraband departments.

Above: Lord Eustace Percy. Public Domain

The cousins had only met briefly during the few years preceding the time when they were together at the Embassy, but Eustace knew Ivar well and from his letters we learn something of Ivar's personality. Ivar engaged fully with his new job, his sense of humour shining through, and he was painstaking and accurate when undertaking routine work. Although he was quick to grasp the complications of international diplomacy, Ivar's main interest in his diplomatic work were the difficulties and developments of employment in America. At the time there were new social experiments and radical movements which interested Ivar. He considered them from a human rather than political point of view, so it is unlikely that he would have made a great political diplomat.

During his time at the Embassy, there were several important international crises, including an armed rebellion in Mexico, and controversy over control of the Panama Canal. There were also internal problems with active radical movements and labour disturbances, meaning there was a lot of work for the Embassy. A small country place was established by the Embassy in New Hampshire and Ivar was in his element there. It was a beautiful and rather wild place, where he could walk and enjoy nature, meet with friends. He was very happy.

In March 1914 Ivar decided to return to Britain. His dream was to open a bookshop in Chelsea, using the name John Cowslip, where he would sell not only books but paintings and drawings by contemporary artists and also, perhaps oddly, holly walking sticks “polished to a high shine” made from materials from the woodlands where he walked. Ivar's dream of a life writing and surrounded by books was ended by the outbreak of war, but it was his plan to resume his dream once the war was over.

Ivar volunteered at once, hoping to serve with the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, but he failed the medical due to his eyesight. Unwilling to be “one of the useless ones” he went to France as an ambulance driver with the American Red Cross Society. In the early stages of the war when America was neutral, the Society was able to raise money but found it difficult to engage recruits to serve at the Front. A single ship, the “Red Cross” or “Mercy Ship” was equipped and sent to Europe. This was better than staying at home for Ivar, but he was not satisfied, becoming quite depressed. Ivar was wounded, leaving him with an injured kneecap, and he was sent home for treatment. On recovery, again Ivar tried to enlist but once more he was rejected. He became rather depressed, so desperate was he to be a soldier. His third application was accepted and he was given a commission as Lieutenant in the regiment of the Campbell Clan in February 1915. He sent a telegram home

“Passed medical. Home for dinner. Kill the fatted calf”

The young man was invigorated and threw himself into training, his injury quite forgotten. The Gazette of 5 February 1915 shows that his commission was with 3rd Battalion Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, a Reserve/Training unit which on mobilisation was based at Woolwich, but in May 1915 was sent to Edinburgh. By then, in April 1915, Ivar was posted to France. This was a really difficult time for Ivar and the family. His father George had been ill with pneumonia and he died on 22 April at Inveraray. The funeral took place shortly afterwards with burial at Kilmalieu as George had requested. The haste was no doubt because of Ivar's need to return as soon as possible to his regiment.

The family was surprised at the contents of George's will. There was no mention of Ivar; everything was to go to Joan, with the understanding that Enid was to be “helped”.

Ivar went to France on 26 May 1915. It seemed unlikely, but he grew to love his life as a junior officer, in particular enjoying the companionship of other young officers, and he saw the army as a career. It was a huge disappointment to him that he was not to remain with his battalion of the Argylls, but there was some consolation as he was attached to another Highland Regiment, the 1st Seaforth Highlanders, which was in the Meerut Division. Despite suffering problematic eyesight Ivar sent home for a rifle with a telescopic sight, so that he could work as a sniper.

Ivar was impressed by the often cheerful demeanour of the men in his command, both in and out of the line. When they were being bombarded by heavy artillery, however, he saw a different side to them:

“Yet under heavy shell-fire it was curious to look into their eyes – some of them little fellows from shops, civilians before, now and after: you perceived the wide, rather frightened, piteous wonder in their eyes, the patient look turned towards you, not, ‘What the blankety, blankety hell is this?’ but ‘Is this quite fair? We cannot move, we are little animals. Is it quite necessary to make such infernally large explosive shells to kill such infernally small and feeble animals as ourselves?’

Ivor was sensitive and recognised the terrifying sense of helplessness that men experienced under heavy enemy fire – a feeling of impotence in the face of devastating fire.

A gifted correspondent, Ivar wrote of his experiences and feelings at the Front to family and friends.

“Utter peace there was this morning- a mist lay about. Near and far is silence, save an eager lark singing. Dogs do not bark in this country now, nor cocks crow – nor bells ring’ The three most persistent country sounds. Only the birds sing on, even above the trenches, brave feathery things to cheer the taut nerves of men” -Ivar, 4 June 1915

Ivar was in Scotland during August, spending time with his family, and they visited Duke Niall at Inveraray Castle. The Duke’s diary records

“Monday 16th August, Woke with a headache which gradually grew worse and I lay down for several hours and had no lunch but got up for tea when Ivar, Joan, Enid and Aunt Sib came to tea. They had not been in the house for two years and liked the electric lights and other improvements very much. Ivar is just back for a few days leave from the trenches and told us much all about it. I hope he comes through it all safe and sound. It is a trying time for Aunt Sibell.”

Duke Niall thought highly of his young cousin, sharing a great love for Argyll. He had no intention to marry and produce an heir, and thought Ivar would be a perfect candidate for the role of his successor as 11th Duke of Argyll.

Niall recorded in his diary on 29 September: “I cycled over to Dunderave (Castle) …I stayed till 4 when Ivar left with Aunt Sib after tea for Dalmally”

Ivar was soon back in France, writing on 29 August:

“We live in chinks of time. This day or tomorrow is nothing of importance”

In September he wrote about the Battle of Loos. His Battalion was in reserve and not involved in the action but Ivar recorded his observations in his usual poetic language:

“Our little show was billed to start on the morning of the 25th……

The Battalion was in Division reserve 700 yards behind the front line. At 4.30, a dull morning, I stood up to watch. There was a trembling of the earth and silently a jet of earth rose into the air, narrow at the summit, broadening at the base where clouds of white smoke gathered…..

Guns of all calibre bombarded for about half an hour – thousands of shells passing over our heads, deafening, roaring, rushing….

Yet in this noise we heard another noise. The Black Watch were cheering as they charged”

A Change of Scene

Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), was important to Britain, being the source of much of the oil, vital for the supply of petroleum to the Royal Navy. British and Indian troops were sent to this part of the Ottoman Empire, in November 1914, principally to protect the Abadan oil refineries. The British Government had a controlling interest in the Anglo Persian Oil Company which produced it. The Meerut Division was among the troops sent East.

Lady Mary Glynn was Ivar’s aunt. She wrote to her son Ralph on 12 November:

“Ivar gone to Mesopotamia & no leave before he went, but I hear he went in good spirits & preferring it to Flanders swamps”

After a train journey through France, their destination was Marseilles.

Above: A halt on the journey to Marseilles. From Captain Ross’ diary – The Highlanders Museum, Fort George.

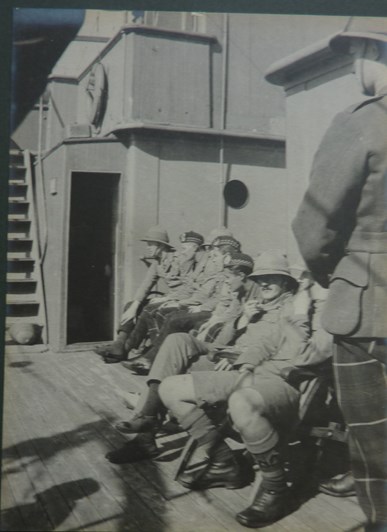

On 25 November they sailed, the officers enjoying comfortable cabins and everyone pleased to be away from the endless damp and mud. They entered the warm waters of the Persian Gulf on Christmas Day.

Above: On board ship. Ivar is seated fourth from the left. From Captain Ross’ diary – The Highlanders Museum, Fort George.

It took six days to complete the journey up the Tigris aboard a river boat, the Julnar. Camp was set up at Ali al Garbi on New Year’s Day. The Battalion, under Colonel Dennys had 26 Officers and 887 men, mainly in overcrowded tents. At least the officers had a decent mess tent!

Above: A halt on the road to Sheik Saad. From Captain Ross’ diary – The Highlanders Museum, Fort George.

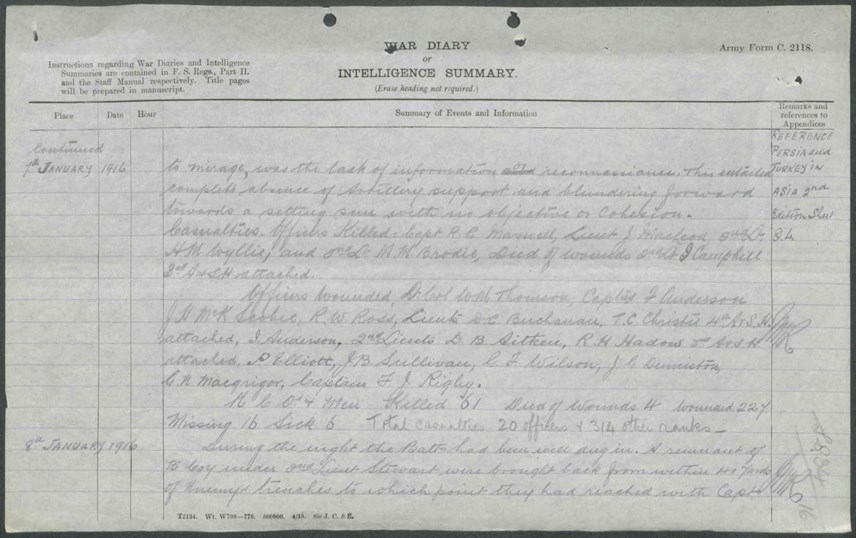

The Battle of Sheikh Saad was fought at the place where the Turkish Army had established a camp housing approximately 4000 troops. The units attacking the entrenched Ottoman forces during the battle did so without the help of supporting artillery, in stark contrast to the opposition, which mounted extremely heavy artillery bombardment.

There was no cavalry, and the foggy weather made it impossible to take advantage of the few aeroplanes available to the Corps; the winter rains arrived along the lower Tigris, turning the terrain into a quagmire of mud.

“Having no cavalry, or aeroplanes, or other means of reconnoitring, and the country being as flat as a billiard table, the only way of reconnoitring the Ottomans was to march on, till we bumped into them.” [George Younghusband, Commander Indian Army]

Pipe Major Neil McKechnie and other pipers led the 1st Seaforth’s attack over the open grounds. One of the pipers later wrote:

“As we advanced over the dead flat open desert the Turks suddenly opened a very heavy fire from well concealed trenches at a range of between 600 to 800 yards. The battalion immediately advanced by rushes towards the enemy’s position in spite of very heavy initial losses..”

Despite the Turkish forces encamped at Sheikh Saad having a clear advantage, at the end of the day the position remained a stalemate. Under the cover of darkness, intelligence gathering patrols were sent out from various British and Empire units, all of which reported that the enemy forces had withdrawn further up the river Tigris. It was a strange decision to move the forces from Sheikh Saad, and the Turkish Commander was sacked was only a few days later.

Perhaps the men and their officers who were killed outright could be thought of as “lucky”. British casualties at Sheikh Saad were over 4000. The provision of adequate medical capacity and supplies had not been high on the list of priorities for the limited transport from Basra; the under equipped Field Ambulances struggled to cope. The Meerut Division had the capacity to cope with some 250 casualties, but was faced with thousands. More than 1000 wounded men were still lying out in the open, with barely even basic first-aid eleven days after the fighting ended and the Turkish left. Of these, approximately 100 were also suffering from Dysentery, and many of those who had been wounded during the ‘Battle of Sheikh Saad,’ later sadly succumbed to wounds.

Captain Ross recorded in his diary:

‘There was great difficulty in getting the wounded in – the majority struggled back in some way or other to the hospital camp which was about 4 miles from the firing line. Almost all the Battalion’s stretcher-bearers were killed or wounded in doing their work & many wounded received additional wounds while they were lying in the open or when being taken back. Bullock carts brought many the last 2 miles but the roughness of the ground & the many small ditches jolted the wounded terribly – Campbell who was hit in the stomach & died of wounds was brought in on one of these carts & this destroyed any chance he had of recovering’.

The Battalion War Diary states: “The action was most disappointing”

There was a brigade casualty total of 20 officers and 314 other ranks for that day. The diary notes that 2nd Lieut. I. Campbell died of wounds.

Above: the 1 Seaforth's war diary entry 7 January 1916

The news of Ivar’s death reached the family on 12 January. Family letters reveal the response to their loss. On 14 January Ivar’s Aunt Mary Glynn wrote to her son Ralph:

“My own darling darling own son

I know how you will grieve for Aunt Syb and for the torture of that faraway uncertainty even in the certainty – 6th or 8th as date, and not having been able to see him before he left – and his not being with the Argyll & Sutherland Aunt Em thinks has added to the sore trouble, “the sore blow” as Aunt Syb calls it. She sees Aunt Far, and all his special friends – and I am sure Eustace Percy will be a comfort to her now.

I saw Aunt Syb & Joan the week before. She had been made so glad by letters on Xmas Day and New Year’s Day. Aunt Far wrote to Aunt Eve that Mrs McDiarmuid (Tiree) had written to her, “I am thinking of the Highland bonnets on their way to where the Tree of Life grew”.

The Campbells were a family with strong beliefs in the afterlife, and Duke Niall wrote to Ralph about a message his mother Lady Archie Campbell (“the Gritts”– Janey Sevilla Callander) had received for Aunt Sib, Ivar’s mother.

Ralph’s sister Meg wrote to him on 18 January:

“I have not seen Joan or Aunt Sybill yet… I have not gone near them since I heard the news of Ivar’s death. Of course I wrote at once, & got a heartbroken note from poor Aunt Syb. It is such a shattering blow for them, & she said in a few days she could face seeing people, but I can’t bear to push myself there until they want one. Joan Lascelles came in here to see me on Saturday evening last. She had seen Aunt Syb & said she was too wonderful for words. But poor Joanie looked altered. Who can wonder – one’s heart simply aches for them all. Ivar has been so splendid & done so well in this war. It had made a man of him, & he had such a delightful nature under the different disguises he assumed. Isn’t it an awful, awful tragedy”

Ralph’s sister Maysie wrote to him on 22 January:

“Isn’t it too ghastly about Ivar. Poor dear Aunt Syb. One hardly dares to think of the black desolation of her sorrow. She writes too wonderfully. No word of complaint or regret, only thankfulness that he so played the game – & by heaven he did….”

Meg wrote again to her brother on 31 January:

“I haven’t seen Aunt Syb or Joan since getting your letter, so have not been able to give them your message. But Aunt Syb told me that Ivar’s Battalion had been through such awful fighting that all the officers including the Colonel seem to be killed or wounded & she doesn’t know how – if ever – she’ll hear any more about Ivar. It’s so tragic. I do feel so miserable about it, and she is so wonderful.”

There is a heart-rending letter from Sybill on 5 February when she wrote to Ralph:

“Feb 5 [1916]

2 Bryanston Square

Dearest Ralph

I loved your letter. I knew how sorry you would be. I have today had two long letters from him – the last dated Jan 1st – he was so wonderful in his love & care for me – he wrote nearly every day ever since he went to France last May. It seems so cruel that he should have been six months in those awful trenches unhurt – & then killed the first month he landed in Mesopotamia.

Oh! Ralph – it’s hard to lose him – my only one – nothing left of Uncle George’s name to carry on – so darling – so clever. Thank God when the war broke out he saw the path of duty & never rested till his feet were on it. He did his duty well & simply & I know he did it well & was a good officer – still praise of him is sweet & it was like your dear self to say you always heard how well he did – please tell me anything you hear – I have had no details yet – these details I long, yet dread to hear – but I can’t hear yet; the battalion suffered so awfully. I feel I may never hear all I want.

Life is over for me – that sounds ungrateful – when dear Joan is all in all to me & so miserable – but some day, like Enid, she will marry & be absorbed in another family. Ivar was just mine – always – even had he married – & oh! How I long for him – the desolation is too awful.

Your very affectionate

Sybill Campbell”

And from Duke Niall to Ralph:

“22 Feb 1916

28 Clarges Street

Mayfair, W

My dear Ralph

I was glad to get your letter yester even. News at last about Ivar’s end, he was hit through the lungs 7th Jan and died on the 8th without gaining consciousness, it was on the 8th that the queer light dancing on the lawn appeared at Inveraray & Niky came to my room about 8 pm and told me of it and I made a note of it at the time. Within a week the Fritts, though she did not see him, undoubtedly got a certain message from him to pass on to Aunt Sibell [sic] and once since then, viz last week she heard a certain thing which only Ivar could have said. He amongst other things said that as to the end he remembered nothing whatever and that he would try somehow to get through to Aunt Sib, hard as it was. But if she heard anything she would be sure to seek a cure in her pill box.

Your affect. Cousin

Niall”

The personal details we have are due to the copious family correspondence and because Mary Glynn wrote such detailed and numerous letters to Ralph. This one is from 8 February:

“Then I went to Aunt Syb. My first visit [since her son Ivar’s death]. She was so pleased with your letters, and with all you had said to her. I had no idea my letter gave you the first news? She still gets letters, the last on New Year’s Day, and all full of the interest & newness & picturesqueness, & pleasure in surroundings. He spoke of being surrounded by Arabs “always friendly as we advance but enemies in any retreat”. He did not speak of any contretemps then. Aunt Syb was very natural, and spoke of him freely, of her life as closed, and “no man left belonging to her”. One knows it to be the blow from which, for her, there is no recovery or relief, & yet she says “if she had had ten sons she would have wished them all to go, and that she is glad it was in a fight, & “not a sniper” or other “lesser path to glory”. That it would have been his wish if it was to be. All this & much else that for me does not relieve the tragedy & the pathos of a life that seemed to need such other crowning – but some day I hope his letters will be published, and the story told of all he did when the great call came, & with it a vocation to which he gave so great an answer.

She minds now the ten days she might have had with him at Marseilles while he waited, &somehow she knows he got no letters all that time & no word from home”

Sybill continued to receive letters from Ivar, and Maysie wrote to her brother:

“We’ve just had tea with Aunt Syb. She got another letter from Ivar written Jan 1, last Friday. It’s awful for her, & yet I think there is most joy, rather than pain, the hopeless silence is for a moment filled, though but as it were by an echo. Joan looks pale & oh so sad. She’s wonderfully brave & unselfish to Aunt Syb. Poor little Joanie…”

On 16 February Mary again gives some idea of the suffering experienced by Sybill:

“I hear that Aunt Syb has been getting more letters from Ivar, all happy ones. He loved being out there. But still no news about the fight he died in….”

And on 27 February:

“I hear today Aunt Syb has heard from Ivar’s Colonel and from the Chaplain, saying all they can to comfort as to not much suffering, [but?] one would not be able to believe much in that agony of far off-ness, and yet I know she has been much helped by knowing he died in hospital…”

And on March 16:

“When he left after dinner Aunt Syb read me some of Ivar’s letters, he certainly knew how to write & drew such wonderful descriptions. He was happy to go to the East & his letters to the last were cheery. He was one of the first to be wounded in that battle, & they got him down to the Base Hospital. He was shot through the chest & lungs & lived about 24 hours after it, only partly conscious, & described very well by a nice chaplain, whose letter has been a great comfort to Aunt Syb, as if Ivar were “like a man on the edge of a deep sleep. He complained at last of feeling sick & sat up in bed. They came at once to dress the wound again & he fell back dead in their arms. He wanted to be brought home but that of course wasn’t possible & they buried him on the banks of the Tigris. Poor darling Ivar, such a gallant soldier he made, & Aunt Syb says he had made up his mind to stop in the Army. He had great gifts & so good looking, how well I remember all our games when we were children here together, & when we climbed trees beside the river at Kilravock….”

Ralph was attempting to find out where Ivar had been buried, and a contact wrote on 30 March:

“HQ

13th Div

30/3/16

My dear Glyn

So far I have been able to find out nothing about Ivar Campbell’s burial place but I have only been up country (Staint Saud) a few days and will do all I can to find out.

I have written to one Macrae in the Seaforth Highlanders who got a DSO on 7th Jan and he may be able to put me on the track.

I hope before you get this that the relief of Kut will be history! I may not say more as every letter is censored but where you are you probably know officially sooner than I can give you private news.

Not too hot yet but stoking up.

Yours ever

Douglas Brownrigg”

Above: Ivar Campbell is remembered on Panel 41 at Bazra.His exact burial place is unknown.

After his death, his friends and family published a small memorial book, “Letters of Ivar Campbell”.

Guy Ridley wrote “He was known to his friends not merely as a beloved companion, 'but also in the several roles of the poet, the artist, the reader, the talker, the tramp, and last, of course, the soldier.'

Sybill arranged a Bursary in his name, setting aside £1,000 to provide for the pupils attending Inveraray High School in memory of her son.

His name appears on the fine War Memorial at Inveraray, unveiled by his cousin Duke Niall.

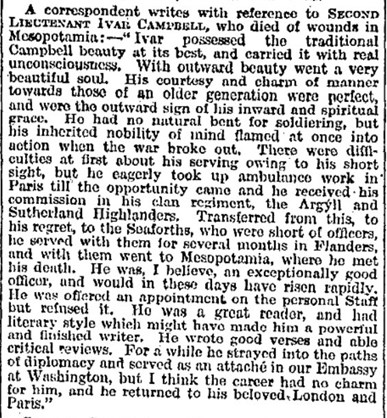

Above: Clipping kept from The Times

The acute loss suffered from Ivar’s death is a timely reminder that every strata of society was affected by the Great War. The mighty Campbell Clan suffered in the same way as millions of other families by the loss of this precious and much loved family member. The work of the junior officers in the Army was the most dangerous job of all – the average life expectancy of a subaltern on the Western Front was just six weeks.

Article contributed by Ann Galliard

Further reading: The Road to Sheik Sa’ad

Notes

Lady Mary Glynn was Ivar’s aunt, the daughter of George Douglas Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll and Lady Elizabeth Georgiana Sutherland-Leveson-Gower and she was his father’s sister.

She married Rt. Rev. Hon. Edward Carr Glyn, on 4 July 1882.

Her son Ralph, the recipient of many of the letters quoted, was six years older than Ivar and was a soldier who served with distinction.

The article is largely based on documents held at Inveraray Castle, and thanks are due to His Grace The Duke of Argyll for access to such personal documents.

The Argyll Papers is a rich resource for Scottish and British history from the thirteenth century to the twenty-first. It attracts visitors from all over the world, researching a wide range of subjects including family and local history, Gaelic studies, place names, military history, political history, economic and social history, agriculture and industry, architecture and more.

Military papers, from the 16th to the 20th centuries, include militia lists, muster rolls, accounts and correspondence records relating to the Argyll Militia, Territorial Army and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, with papers relating to the First and Second World Wars. There is a large collection of personal and business papers of family members, 16th – 20th centuries, along with personal diaries, photograph albums and sketch books.

For more information about access contact Alison Diamond, Archivist

archives@inveraray-castle.com

Tel: 07943667673

www.friendsoftheargyllpapers.org.uk

Friends of the Argyll Papers, Cherry Park, Inveraray, Argyll, PA32 8XE.