The First World War story of Captain A.D. Blair, Harley Couper's great-grandfather.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The First World War story of Captain A.D. Blair, Harley Couper's great-grandfather.

At the back of my parents' wardrobe sat a pirate's chest. It would grumble and sigh camphor when opened, hinting at distant lands and adventures. The pirate was Captain A.D. Blair, my great-grandfather. His adventures, my mother hinted, included smuggling guns in the Middle East, sailing the seas with a pet lion aboard, and earning a medal from the Sultan of Somewherearather.

The truth, it turns out, was far more interesting.

Born in Dunedin to Scottish immigrants, John and Martha Blair, he grew up in a city that was exploding with new churches, museums, art galleries, universities, and high schools. It was the salt air of Port Chalmers that grabbed the teen’s imagination, however, so in January of 1889, the barely 16-year-old signed a Covenant of Indenture, ‘voluntarily binding himself as an apprentice with Peter James Hughes,’ Captain of the Barque ‘Laira’. Hughes, in turn, was to ‘use all proper means to teach the said apprentice the business of a seaman’. Blair spent his final teen years on the ‘Laira’, mostly transporting wool from New Zealand to England. The barque is a small ship with three (or more) masts, rigged with square sails on the front masts and only fore-and-aft sails on the final mast, or mizzen. They were considered reliable merchant ships, the pack horse of ocean-faring vessels. In the emerging era of steam power, the barque was an economical option for long-distance haulage, where small crews untethered to coal supply lines were an advantage. Young Blair didn’t know it at the time, but his future would see him in command of the pirate-favoured brigantine, and in a time of war, no less. The brigantine had only two masts, the foremast rigged with square sails and the final mast, or mizzen rigged fore and aft. For now, though, the young teen had to earn his sea legs, which he recounted later as an old man, meant the force-feeding of porridge until he no longer threw it up.

Sailing into modern northern hemisphere ports, the Laira might have looked a little old-fashioned alongside the modern steamboats plying the coastal routes, but that was the least of his worries. Blair's apprenticeship was physically demanding and often dangerous. On more than one occasion, he witnessed sailors fall from the rigging, dashing their brains on the deck below. During his last year of apprenticeship, his own 'master' was fatally crushed by falling timber in the Port of Fremantle. In June of 1893, he completed his apprenticeship under Gordon MacKinnon and began his adult working life. Within ten years, he had earned the qualifications needed to be a Merchant Navy Master of foreign-going ships and square-rigged vessels.

This is where it gets interesting.

Blair had begun working for the Clan Line, a growing line of steamers carrying passengers and cargo around the Persian Gulf. In particular, he was commanding ships in and out of Aden, Yemen, at the mouth of the Red Sea. The whole region was full of tension.

The Ottoman Empire, which controlled the area, was under considerable stress. The Italians would attack North African territories in September of 1911, but even before then, internal tensions among Arab and Bedouin tribes often saw localised revolts against Ottoman rule and taxation. Later, Lawrence of Arabia would exploit these tensions against the Ottoman Empire. For now, though, the empire had a few more years before it would come apart at the seams. One local revolt, in July of 1911, occurred in the coastal town of Al Luhayyah, Yemen by the Red Sea near where Blair was operating commercial steamers. The Ottoman garrison there found themselves under siege and without access to the water wells. Blair was asked to transport troops from the island of Kamaran, 35 kilometres away, closer to the siege site but in a surprise move, ran a gauntlet of fire to deliver the troops. He then stayed for a further five days until the wells were recaptured, providing troops with fresh water from his ship’s ballast and onboard condenser. For this, he was awarded the Order of Mejidie (4th class) and was addressed using the title ‘Bey’, a kind of ‘Sir’ or ‘Lord’. The title he believed was unofficial. Months later when the Italian-Ottoman War broke out in earnest, the Italian Destroyer Granatiere pursued Blair in the Red Sea, overtaking and boarding the British steamship ‘Tuna’ before taking it back to port for inspection. Photographs taken at this time are notated in Blair’s hand as ‘running contraband for the Turks’.

Perhaps this was the grain of truth behind the family story that Blair had been a gunrunner in the Middle East. But what about the pirate bits? Was there any truth to that?

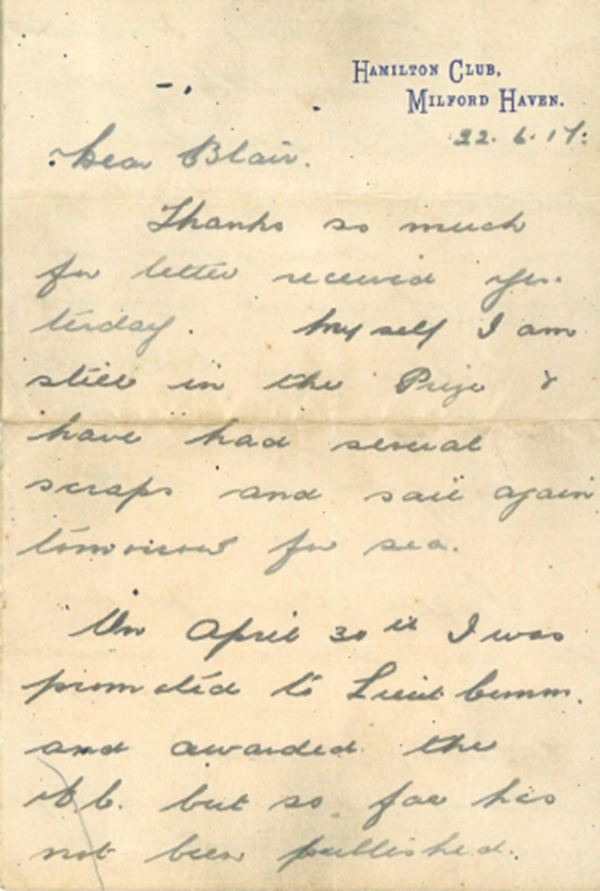

The answer is, sort of. And it involves the well-known New Zealander and the Victoria Cross recipient, William Edward Sanders (1883-1917). However, in 1914, at the outbreak of the First World War, Sanders was still two years away from enlisting with the Royal Naval Reserves. The now 41-year-old Blair had enlisted already and was Lieutenant aboard HMS Defiance, a torpedo and wireless school ship before being put in command of a unit of six patrol trawlers, based at Milford Haven in the southwest part of England. Trawlers, fishing vessels with large open decks set up for long periods at sea, were easily converted for military purposes. They were armed with light weaponry and tasked with intercepting enemy supply ships, coastal patrol and surveillance, and the location and clearing of mines.

He began his patrols in January 1915, and in the following month, Germany declared the seas around the British Isles a war zone. Any allied ship in the area could be sunk without warning. In May, the luxury ocean liner RMS Lusitania, whose launching Blair had attended back in 1907, was sunk off the coast of Ireland by the German submarine u-20, with the loss of 1,959 passengers. Public outrage was fierce, and military minds were faced with the problem of unrestricted warfare where civilians were as much a target as military personnel. Before Blair could play a role in that dilemma, however, 12,000 Irish Volunteers and Citizen Army members attempted to take over key locations in Dublin from British rule in what became known as the Easter or Sinn Fein rising.

Three days after the initial rebellion in Dublin, Blair took troops from Kingston Port, now Dublin Port, 70 kilometres south into the Port of Arklow to secure the Kynoch's Explosive Works. During the First World War, this township/factory was producing 7½ million cartridges per week alone. They also produced cordite, gunpowder, acetone, shell cases, and detonators for the war effort. Vice Admiral Charles H. Dare would later commend Blair for ‘the arrangements he made to defend the town and munitions factory during the Sinn Fein rising, ‘noticing that he "carried out charge of naval operations for the protection of Arklow … with marked ability and promptitude’. The Vice Admiral of Old Milford Naval Base noted in Blair's military record, ‘I have a very high opinion of this Officer’.

Blair was transferred into the Special Service a few months after the Easter Rising and instructed to take receipt of the Dutch-built Helgoland (1895) in Liverpool and sail her down to Falmouth for refit. Naval Command, in response to the unrestricted attacks on commercial and civilian shipping by German u-boats, was creating a new class of military vessel. Sailing ships and occasionally steamers were being refitted as decoy vessels, designed to look like an easy kill. Their role was to lure German u-boats to the surface to be sunk using traditional guns rather than expensive torpedoes. Originally called Special Service ships, S.S. For example, they were subsequently all given Q numbers. Helgoland then became Q-ship 17, or Q.17.

Q-ships were not, however, easy kills. Often light and manoeuvrable, some with very shallow drafts, their hulls could be filled with buoyant woods and barrels, making them difficult to sink even after taking a real pounding. Deck houses were modified so that with the pull of a pin, the sides could fall away, revealing 12-pounder guns. Crew members wore civilian clothes, some even dressing up as the captain’s wife. Crew numbers on deck were limited to what was common for each particular decoy. A ‘panic party’ was trained to make a show of abandoning the ship in a life raft, leaving fighting marines hidden on board. When the u-boat finally approached close enough to record the ship's name, the deckhouse walls would fall away, and the 12-pounder guns, along with other small arms fire, would target the u-boat on the surface. It was part theatre, part skulduggery during a time of genuine danger for commercial and civilian shipping. It’s also the closest we can get to that childhood belief about my pirate ancestor. Q.17 was not exactly a pirate ship, but it was a brigantine, armed to the teeth, which, along with the Sloop, was the ship of choice for pirates of old.

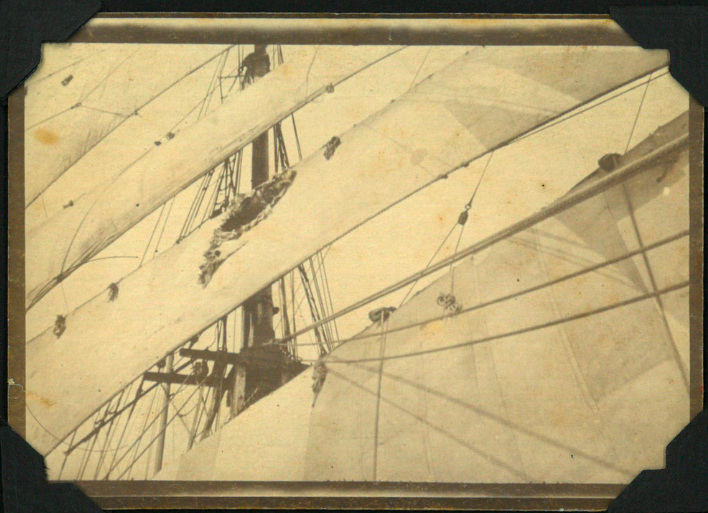

As a brigantine, Helgoland’s sails were configured for speed and agility in both strong and light winds. She had two masts. The foremast had four square sails, which gave it power when running before strong winds. The multiple headsails, jibs, at the front helped with manoeuvrability and speed, especially when sailing upwind. The main mast at the rear was fore and aft rigged. The large gaff-rigged mainsail gave it good performance when sailing perpendicular to the wind, and above that sail was a gaff-topsail, which provided additional power in lighter winds. Between the masts were staysails, smaller, triangular sails used on a brigantine for better manoeuvrability and speed, particularly when sailing close to the wind, or (nearly) directly into the wind.

Blair oversaw the Helgoland’s refit in Falmouth. The captain's quarters on deck at aft had access through a trapdoor and were fitted with two 12-pounder guns, and walls designed to fall away with the pull of a pin. The bow of Q.17 had port and starboard deck houses, and each of these likewise was equipped with a 12-pounder gun.

During the refit, Blair had assigned to him as Navigator, fellow New Zealander, Sub-Lieutenant William Edward Sanders (1883-1917). Nine years Blair's junior, Sanders had begun his career with steamships but before the war had worked for Craig Line under sail and gained his mate's certificates. Sanders would eventually go on to become Lieutenant Commander Sanders, winning the Victoria Cross aboard HMS Prize, or Q.21. The two would keep up a correspondence until Sanders was killed in action on August 13, 1917.

The first time they took Helgoland out into open waters with 25 crew, and one ship’s dog hidden on board, they headed into the English Channel near Lizard at the southern tip of England. It was September 7, 1916. German u-boats that day alone attacked seventeen ships, sinking fifteen of them. At about one o’clock in the afternoon, the winds dropped, and Blair found Helgoland becalmed. Having no engine and no wind, the Q-ship had become a sitting duck. At this worst possible moment, a u-boat was sighted approaching on the starboard side from behind the ship. It was less than two kilometres away but steadily drawing near. A bell sounded, and crew members crept quietly to their assigned positions. As the u-boat approached, it began to shell Helgoland. One of the first shots blew away her ensign at the top of the mast. ‘Skipper Smith’, recalled Blair later, “was sent aloft with the ensign to make fast to the backstay above the crosstrees as the halyards had been shot away. After lashing the ensign to the backstay (he) asked permission to remain and spot the shot…some nerve!”

The u-boat drew nearer, firing as it came, and Blair realised that their own guns would soon lose a clear line of sight on the u-boat. After the u-boat's fourth shot, and earlier than practised, they lowered the screens around Helgoland's hidden guns, and the brigantine, its identity now revealed, answered shot for shot. Smith shouted down the warning that another u-boat had surfaced on the port side, and a fishing boat had appeared astern. The second submarine soon opened fire, but Blair, firing from the “captain's quarters,” and Sanders from the starboard bow gun, focused their efforts on the initial u-boat. A shot landed, striking the gun pedestal of the attacking submarine, and the now-damaged vessel began to submerge. The port u-boat at Blair and Sanders back likewise submerged before guns could be brought to bear. The submarines had not expected to be fired upon, but the early reveal had weakened the trap, allowing at least one to escape.

Up in the rigging, the astonished Skipper Smith watched as the fishing vessel at their stern steadily rose out of the water. Now draped in its sail disguise, the swollen waters around a conning tower melted into the deck-mounted guns and steel grey body of a third submarine advancing as it emerged from the English Channel. Blair and Sanders attempted to bring Q.17’s guns to bear but found immovable portions of the deckhouse in the way. The absence of any wind continued to rule out manoeuvres, so with axes and crowbars, they desperately attacked the deckhouse, fully aware that the moment the u-boat levelled on the surface, its forward guns could begin their work. As the deckhouse structure gave way, the dismayed New Zealanders realised the u-boat had unwittingly positioned itself perfectly, with Helgoland’s wheel aft, or helm, exactly between itself and the Q-ship's rear 12-pounder guns. The submarine fired several rounds, one of them passing the length of the boat above the men’s heads and punching through one of the foremast’s square-rigged sails. Realising Helgoland was not the defenceless craft initially assumed, the third u-boat dived below the surface, just as the starboard and port attacking submarines had done.

It was suddenly quiet.

All but one of the crew, the dog, had remained calm throughout the previous hours. Now they stayed at their posts, alert at the guns, watching, but also listening. Although u-boats were powered electrically, during the First World War, the batteries were charged by diesel engines when the vessel was on the surface or at periscope depth where vents at the top of the conning tower could allow fresh air in. The afternoon slowly faded into dusk, and then the deep black of night, and still they waited. Q.17 had now given away any element of surprise. Her guns lay exposed on the deck, and each gun with its crew on hand put the number of men on deck well above what was normal. A surfaced u-boat would be very unwise to approach at this point. From the front of the boat on the port side, an irregular mechanical clattering emanated from the water’s surface. It travelled down the length of Q.17 and around the stern. Some of the crew tried to track the sound, searching for any sign of a periscope as it rounded Q.17 and travelled up the starboard side. Someone briefly glimpsed the submarine but then lost it as the strident clatter of an early diesel engine faded away.

A patrol trawler was sighted, and Blair hailed it, explaining the presence of a u-boat in the region and their need for a tow back into Falmouth. The trawler manoeuvred around the bow intending to come alongside when a shout went up. In the moonlight on the water’s surface, the wake of a torpedo was sighted, tracing a path directly toward them. Sanders sprang to the port side gun as the torpedo missed the trawler and passed straight under Helgoland’s shallow draft. He fired a round off, using the wake to estimate the u-boat’s location. In haste, the trawler came alongside, sailors at the ready to fasten a line to the brigantine. A second torpedo wake was spotted, and the men braced for impact, but the u-boat had not yet managed to account for Helgoland’s shallow draft. It passed harmlessly beneath the Q-ship.

Q-ship 17, Helgoland, and her crew of 25 men and one dog under the command of Lieutenant A.D. Blair and navigator Sub-Lieutenant William Edward Sanders were towed back into Falmouth port on September 8, 1917. As soon as it docked, the ship's dog bolted from the deck of the Helgoland, never to be seen again.

Blair and Sanders would keep up a correspondence after their time together on Q.17. Sanders would later command his own Q-ship, the Prize (Q.21). Often described as a schooner, Q.21's two small square-rigged sails at the top foremast suggest it was more a barquentine. His actions in command of the Prize earned him the DSO and the VC. He sent Blair photographs aboard Helgoland of damage received on September 7, 1917, including a photo of himself developed in reverse. His letters reveal how tired he was and inform Blair about the DSO and VC awarded, asking him to keep the news secret for now. Two photographs sent to Blair are often misattributed to Sanders aboard the Prize. It isn’t easy to see however how Q.17's four large square-rigged sails could pass for the pair of sails on Q. 21’s foremast topsail, or how a camera from 1917 might take such a close photograph of them.

At the back of my wardrobe sits a pirate's chest, you might think, though it’s actually a footlocker. It grumbles and sighs camphor when opened, hinting at distant lands and adventures. The ‘pirate’ was Captain A.D. Blair, my great-grandfather. His interesting life didn't begin or end with the First World War but included shipwrecks, yellow fever, a ship carpenter’s daughter, the British Occupation of the Rhine, and a court martial.

More can be gleaned on Te Ao Mārama - Tauranga City Libraries’ online archive Pae Korokī.

The information for the above account comes from Blair’s photograph album, newspaper articles, his military record and certificates, letters from Sanders to Blair, and the stories told by the wider Blair family during a reunion in 1991. His account with the u-boats comes from a talk he gave in Auckland during his retirement, Chatterton’s ‘Q-ships and their story’ (1922), and his marginalia in his copy of the book.

Article by Harley Couper, Heritage Specialist, Tauranga City Libraries.