Operation Michael, The Thirty Worst and an Advanced Dressing Station

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Operation Michael, The Thirty Worst and an Advanced Dressing Station

March 1918 was arguably the most critical month of the First World war for the British and Commonwealth forces in France. On 21 March, the Germans launched a massive attack with the aim of knocking the British out of the war.

Above: Left to right - Chief of the General Staff, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg; Kaiser Wilhelm II; 'First Quartermaster General' (as he was titled) General Eric Ludendorff

This assault was a calculated gamble by the German commanders, Hindenburg and Ludendorff. They were acutely aware of the imminent arrival of large numbers of troops from America (the USA had entered the war in April 1917 but the build-up of her forces was not yet complete). Also, the recently signed peace treaty between Germany and Russia meant that many of the Kaiser's soldiers could be shipped to the Western Front, giving the Germans a temporary advantage in numbers.

Having decided to make an all-out assault, the next question was where it should take place. For a variety of reasons, the decision was made to attack towards the Somme. It has been argued that the choice of the Somme for this battle "Kaiserschlacht" (Kaiser's Battle) to the Germans - was a major error of judgement. Although it had the advantage of being at the junction of the British and French sectors, it would involve the Germans having to deal with the logistical problems of supplying the troops across the waste-land of the old Somme battlefield of 1916.

Despite the challenges, this area was selected and Ludendorff is recorded as saying "punch a hole and things will develop." With this in mind, overwhelming numbers of troops and artillery were assembled in secret on a front extending over 40 miles from La Fère in the south to Arras in the north.

Additionally, artillery techniques, perfected by Colonel Bruchmüller were incorporated into the plans, which involved neutralizing Headquarters and communication centres in the rear areas as well as the extensive use of gas shells.

Colonel Bruchmüller

British Forces

The temporarily favourable conditions in which the Germans found themselves can be contrasted with the position of the British Army at this time. The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, wished to limit Sir Douglas Haig's ambitions and had deliberately kept Haig short of reinforcements. This resulted in Haig having to re-organise his forces.

Lloyd George (right) in conversation with General Sir Douglas Haig (second from left), at Meaulte, France, 1916.

In January and February of 1918 the number of battalions in an infantry brigade was reduced from three to two. Although this may not seem too difficult a proposition to deal with, this shortfall meant that the usual rotation of battalions in and out of the front line was no longer possible.

Besides wrestling with this and many other tactical issues as a result of the reorganisation, there was also the necessity of having to disband or merge dozens of battalions, many of which had been fighting for months on end. Nevertheless, the decision to dissolve these units resulted in thousands of men being removed from environments to which then had grown accustomed and ordered into new units with which they had no attachment or affinity.

The 31st or Thirty Worst

The 31st Division is as an example of the difficulties that were encountered at battalion level by this reorganisation. The division had first seen action on 1 July 1916 in the attack at Serre.

Above: The divisional sign of the 31st Division

Further attacks were made later in 1916. In 1917 the division was used during the later stages of the Battle of Arras. This attack, at Oppy Wood was a failure. As a result of these setbacks, the men of the division revelled in calling themselves the "thirty-worst" division.

Originally recruited in the North of England, the battalions were raised by local authorities, industrialists or committees of private citizens as part of Kitchener's New Armies. Their subtitles reflect their origins. The division's 92 Brigade originally comprised four battalions of the East Yorkshire Regiment from Hull - there were the Commercials (10th battalion), Tradesmen (11th battalion), Sportsmen (12th battalion and T'Others (13th battalion).

Meanwhile, the 93 Brigade was made up of the Leeds Pals (15th West Yorkshire) two battalions of the Bradford Pals (16th and 18th West Yorkshires) and a 'Pals' battalion from Durham (18th Durham Light Infantry).

The Leeds Pals 'Recruiting Tram'. Image courtesy of Leeds Library and Information Services.

Finally, in the 94th infantry brigade was the Accrington Pals (11th East Lancashire), the Sheffield City Battalion (12th York and Lancasters) and two battalions of Barnsley Pals (13th and 14th York and Lancasters). The divisional pioneers was the 12th King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry: this was also a 'pals' unit formed by the West Yorkshire Coal Owners' Association.

The character of the division was eroded during the months of combat on the Western Front, but the enforced changes at the start of 1918 ensured that it would not be the same again. Two battalions of the Hull Pals (Sportsmen and T'Others) were disbanded; some men went to the other two Hull Pals battalions, but other men were posted away from the division. To replace these two battalions in the brigade came the Accrington Pals.

In 93 Brigade, matters were no better. The Leeds Pals had already been joined by a sister battalion from Leeds and was now the 15th/17th battalion. The two Bradford Pals battalions were both disbanded, with a few of the men reinforcing the Leeds Pals. The 1st Barnsley Pals came across to join the Leeds and Durham battalions in the brigade.

Finally, 94 Brigade was removed from the order of battle entirely, with the Sheffield City Battalion and 2nd Barnsley Pals being disbanded. In place of 94 Brigade came a Guards Brigade, made up of battalions of the Grenadier Guards, Coldstream Guards and Irish Guards.

On the eve of the German offensive, whilst in reserve and out of the line, the division's commanding officer, Major-General Wanless O'Gowan was replaced, with the new commanding officer taking over on 21 March. It may be that this was an attempt at improving the division's reputation.

In the early hours of 21 March 1918 a truly awesome bombardment was put down by the German Artillery. Under the cover of fog, the German infantry advanced.

Kaiserschlacht

Also known as Operation Michael, the German offensive was, in some sectors, fairly successful. Large parts of the British front line were taken and the defending troops pushed back some considerable distance. However, the results of the first days attack were mixed. Despite all the advantages, there was no breakthrough and in some places the attacking Germans lost large numbers of men in exchange for very little ground gained.

German infantry soldiers engage in combat during the Spring Offensive in France in 1918. (IWM Q47997)

Above: A German A7V tank. It is believed this was taken in Roye on 21 March 1918. These German tanks were failures, the Germans preferred to convert captured British tanks.

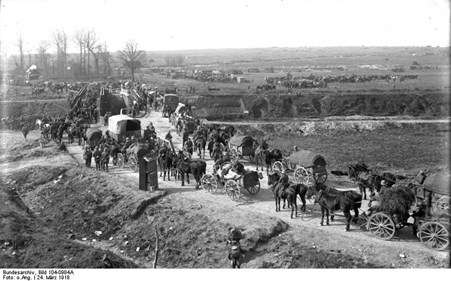

Above: Etricourt, 24 March 1918. German troops on a street in front of two temporary bridges

Although the front extended towards Arras, the town itself was not directly attacked at the beginning of this battle. Running out of Arras was the road to Bapaume, a town located some ten or so miles to the south. The defenders in this sector included the 34th Division, who were heavily engaged and, as they were forced back towards the Arras-Bapaume road, called for reinforcements.

The 31st Division was in 'GHQ reserve' and was ordered up to the front line.

We rode via St. Pol, Frevent, Doullens, and after a very long, hot and dusty day reached Pommier; there, owing to the increased pressure of the enemy, we were ordered to move straight up via Beaumetz-les-Loges to Blaireville, which we reached at 9pm.

War History of the 18th (S) Battalion, Durham Light Infantry

We arrived, after a twelve hour ride, at a lonely spot on the shell-scarred road, from which we could see several villages on fire, the ruddy glow lighting the blackness of the surrounding distance for miles. Here, after dumping all unnecessaries, we were collected together, the 10 per cent were detailed, and then we were quietly told that our task was to hold a trench one foot deep and to hold it at all costs.

20377 Private Percy Barlow, B Company, Leeds Pals

Above: The badge given to members of the Leeds Pals.

The Army Line lay to the east of Boyelles about 300 yards west of the Arras - Bapaume road. The position was well wired, but the trenches were wide and very shallow, and the Companies at once completed portions of the system to give bombardment protection. 4th Guards Brigade was on the right facing Mory, 93rd Infantry Brigade on the left opposite Croisilles ; in the latter Brigade 18th West Yorkshire Regiment was on the right, and 13th York and Lancaster Regiment on the left, 18th Durham Light Infantry being in support. 92nd Infantry Brigade were in reserve. The Battalion details stayed at Blaireville.

War History of the 18th (S) Battalion, Durham Light Infantry

Advanced Dressing Station Hit

Few fatalities were incurred in the infantry battalions of the 31st Division, but at some stage during the attack that followed, it is likely that a long-range shell hit an advanced dressing station. A serjeant and seven other men of the 93rd Field Ambulance were killed on 23 March, and on the same day, and possibly from the same incident Major H Dunkerley, Captain E Cunning plus three serjeants from the RAMC's 95th Field Ambulance were killed.

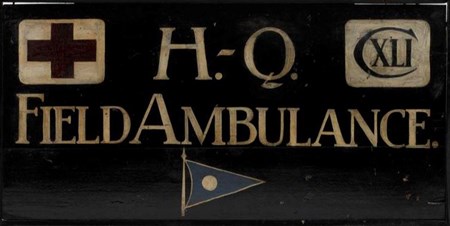

Headquarters sign of 141st Field Ambulance, a medical unit that served on the Western Front during the First World War. (IWM FEQ 372)

Above: Outside an advanced dressing station. (IWM Q33426)

Above: A crowded scene in the courtyard of a bomb damaged farmhouse that has been converted into an advanced dressing station. Wounded British soldiers sit and stand in the courtyard, many bandaged and bloodied but predominantly walking wounded. They are tended to by red cross orderlies with three motor ambulances waiting on the left, one of which is being loaded with a patient on a stretcher. In the central foreground a German prisoner stands beside a British soldier on a motorcycle. (IWM ART 3835)

We know a little about the two officers.

Major Harold Dunkerely (photo: below) was educated at Downing College, Cambridge, where he graduated with a BA in 1912, and then subsequently MA. He then went to the London Hospital, taking the diplomas of MRCS and LRCP in 1914. He acted as surgical clinical assistant at the London Hospital until 1 December 1914, when he took a temporary commission at the rank of lieutenant in the RAMC. He entered the war in France on 19 May 1915, attached as medical officer to the 8th Battalion Rifle Brigade, and served with them for nine months before being wounded and invalided home. After a year's service, he was promoted to captain. Harold returned to France three months later, and served successively with a stationery hospital in Boulogne, with the North Somerset Yeomanry, and then with the 95th Field Ambulance, with which he worked with until his death. He was described by his friends as an enthusiastic worker and one who possessed great personal charm. Harold was the younger son of Mr Herbert Dunkerely of Bombay.

Harold Dunkerely. Source: RAMC in the Great War

Captain Edward Cunnington was educated at Reading College, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, London. Entering in 1912, he obtained the diplomas of MRCS, LRCP in 1915. He then filled the post of house physician and Medical Receiving Room Officer at the hospital. He was a keen archaeologist, who loved studying prehistoric relics, and was a fellow of the Cambrian Archaeological Society. Edward obtained a commission in the RAMC in 1915, and was first sent to Egypt attached to the 95th Field Ambulance, and on his return was appointed medical officer to the 12th Battalion York and Lancashire Regiment, with whom he served for two years in France. He returned to his original unit a few days before his death, which was due to a shell in his advanced dressing station whilst he was attending to the wounded. Edward was the only son of Benjamin Howard Cunnington, JP of 33 Long Street, Devizes; and the husband of Maud Edith Cunnington.

Source: RAMC in the Great War

Above: The Medical Officer of the 12th East Yorkshires, 92nd Brigade, 31st Division, bandaging the face wound of a man of his battalion in the line in the Arleux Sector, near Roclincourt, 9 January 1918. (IWM Q11545)

Most of the men killed in this incident were originally buried in Blairville Orchard British Cemetery. After the war, this was one of the smaller burial plots that had to be 'concentrated' into larger cemeteries. Rather than being reinterred close to where they fell, the men were reburied in Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery about 15 miles away, north of Arras.

One of the fatalities, Private Webb, was buried at the Bac-Du-Sud British Cemetery where he still lays. Sadly, he was one of three brothers who all perished in the Great War.

With obvious care and consideration, the men buried at Blairville Orchard (which included two from the Army Service Corps - both men being attached to the 95th Field Ambulance) were reinterred in the order in which they were originally buried. Indeed, the grave reference numbers are identical.

Bac-Du-Sud British Cemetery (source: CWGC)

TABLE OF RAMC FATALITIES FROM 93 and 95 FIELD AMBULANCE

|

rank |

name |

unit of RAMC |

grave in Cabaret-Rouge |

original grave in Blairville |

|

Captain |

95th Field Amb |

VIII. R. 6 |

I.A.6 |

|

|

Major |

95th Field Amb |

VIII. R. 7 |

I.A.7 |

|

|

Serjeant |

95th Field Amb |

VIII. R. 8 |

I.A.8 |

|

|

Serjeant |

95th Field Amb |

VIII. R. 9 |

I.A.9 |

|

|

Serjeant |

95th Field Amb |

VIII. R. 10 |

I.A.10 |

|

|

Serjeant |

A.S.C. att'd 95 FA |

VIII. R. 11 |

1.A.11 |

|

|

L/Cpl |

93rd Field Amb |

VIII. R. 12 |

I.A.12 |

|

|

Private |

93rd Field Amb |

VIII. R. 13 |

I.A.13 |

|

|

Private |

A.S.C. att'd 95 FA |

VIII. R. 14 |

I.A.14 |

|

|

Serjeant |

93rd Field Amb |

VIII. R. 15 |

I.A.15 |

|

|

Private |

93rd Field Amb |

VIII. R. 16 |

I.A.16 |

|

|

Private |

93rd Field Amb |

VIII. R. 17 |

I.A.17 |

|

|

Private |

93rd Field Amb |

VIII. R. 18 |

I.A.18 |

|

|

Private |

93rd Field Amb |

VIII. R. 19 |

I.A.19 |

|

|

Private |

93rd Field Amb |

Bac-Du-Sud |

n/a |

Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery

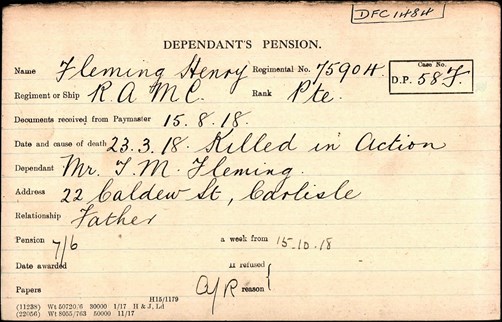

Among the men killed in the 93rd Field Ambulance was a pair of brothers, Henry Fleming (aged 25) and Thomas (aged 21) from Carlisle.

The personal inscription on their headstones is unique. On Henry's is "Until the Day Break". Whilst on Thomas's the quotation continues "And the Shadows Flee Away" [Song of Solomon 2:17]. It is likely that this arrangement, where the inscription continues from one headstone to another is not repeated in any other CWGC cemetery.

Above and below, the personal inscriptions on the headstones of Henry and Thomas Fleming.

Adjoining the grave of Private Hardy at the end of the row is Private WH Ward of the Leeds Pals. It is highly likely that he was one of the patients at the Advanced Dressing Station at Blairville which was hit on 23 March.

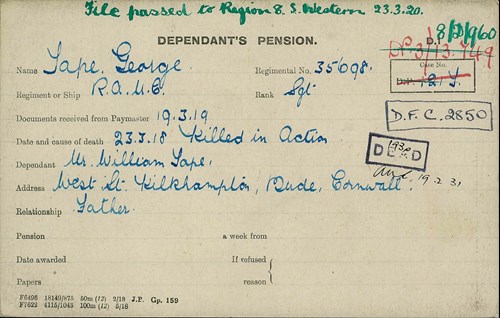

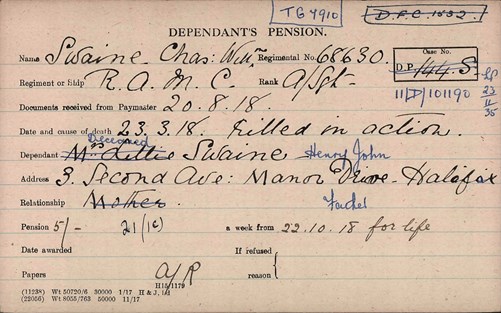

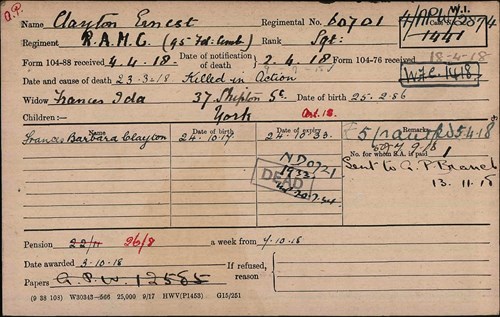

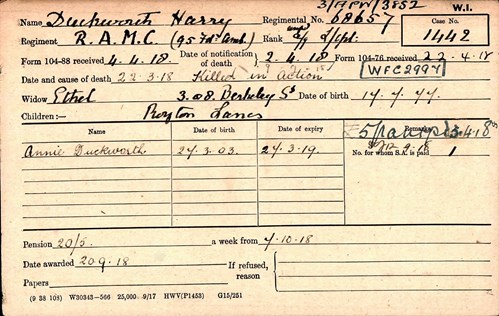

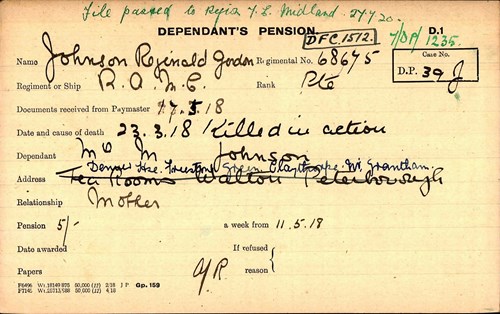

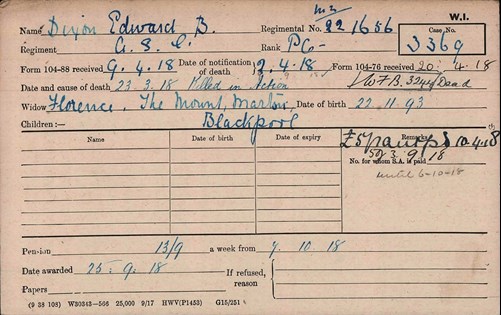

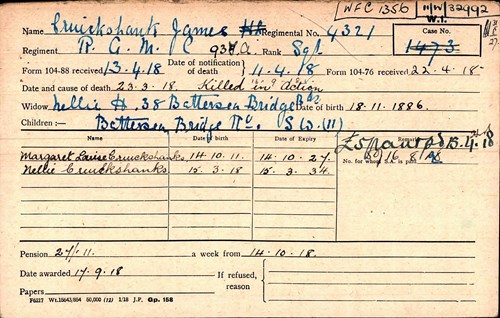

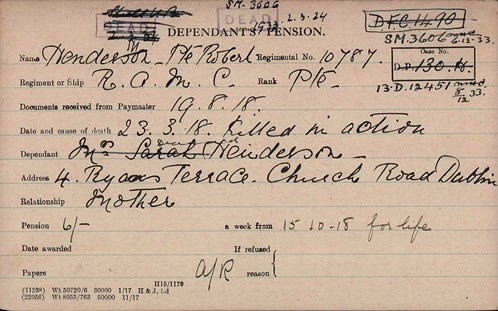

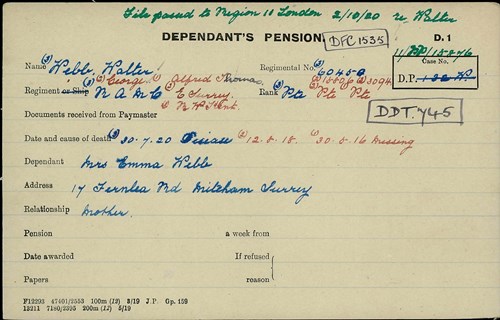

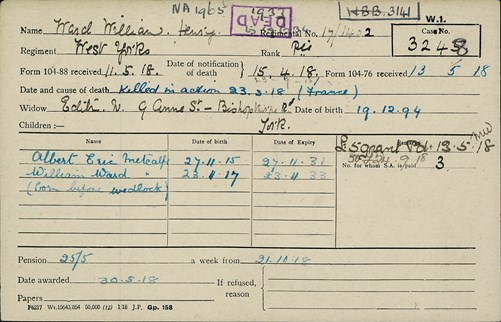

Using the WFA's Pension Cards we can find out a little bit more about most of these soldiers. Their cards are reproduced below.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association