Pantomime at Sea: Q-ships in the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Pantomime at Sea: Q-ships in the First World War

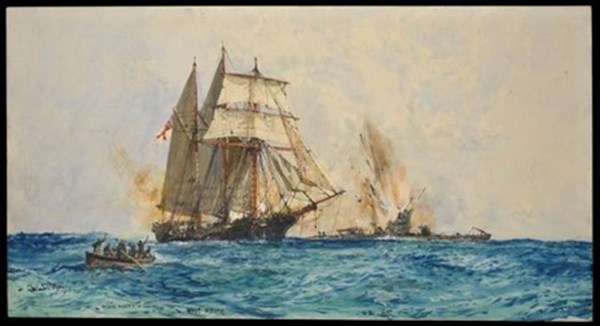

The use of deception in warfare at sea was not new to the First World War – as an example, in 1681, HMS Kingfisher was designed to counter the attack of pirates by masquerading as a merchant ship, with her armaments hidden behind false bulkheads, and with various means of changing her appearance. Conversely, the tactic of making merchant ships look like armed frigates was also employed.

Above: Painting 'The Action of the Kingfisher with Seven Algerine Ships, 1 June 1681' by Willem Van der Velde. (Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

From the start of the war, U Boats wreaked damage with the loss of HMS Pathfinder on 5 September 1914, followed by Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue - all sunk within an hour of each other - later that month. Merchant shipping was also under threat although in the early stages of the war, U Boats observed the ‘prize rules’ of the time, which meant that they surfaced before attacking merchant ships and allowed the crew and passengers to get away. This of course left the U Boat vulnerable whilst on the surface.

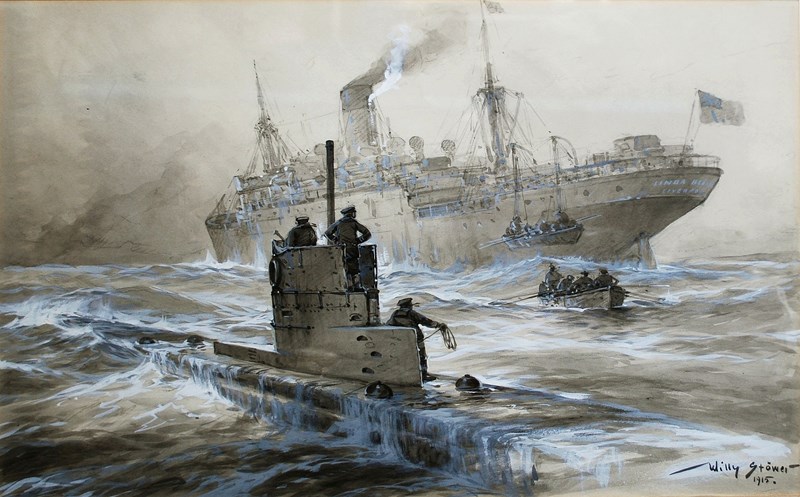

Above: Sinking of the Linda Blanche out of Liverpool by German painter and illustrator Willy Stöwer (1864-1931)

The impetus of the decoy ship initiative, also called ‘mystery’ ships and later known as Q Ships - thought to be due to their links with Queenstown harbour - in WW1 is often attributed to Churchill, who sent a telegram to the Commander in Chief at Portsmouth on 26 November 1914 thus:

‘It is desired to trap the German submarine which sinks vessels by gunfire off Havre. A small or moderate sized steamer should be taken up and fitted very secretly with two twelve-pounder guns in such a way that they can be concealed with deck cargo or in some way in which they will not be suspected. She should be sent when ready to run from Havre to England and should have an intelligence officer and a few seamen and two picked gun layers who should all be disguised. If the submarine stops her she should endeavour to sink her by gunfire. The greatest secrecy is necessary to prevent spies becoming acquainted with the arrangements’.

Shortly afterwards, the Admiralty ordered its first decoy ship. Meantime, armed trawlers working with submarines accounted for some U Boat losses in the first few months of 1915.

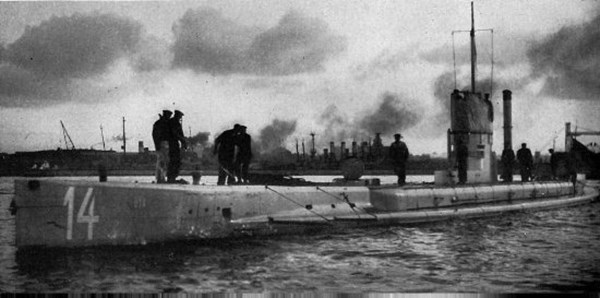

Above: U-14 was sunk by the armed trawlers Oceanic II and Hawke off the coast of Peterhead on 5 June 1915. Part of the George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).

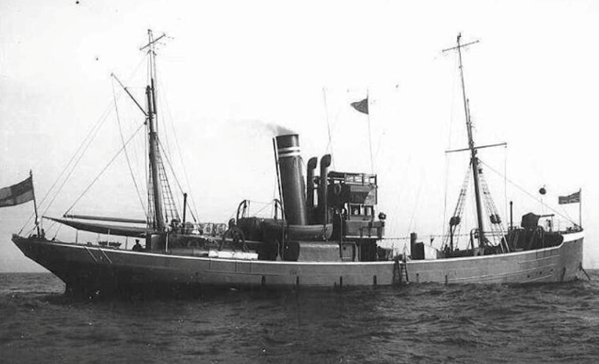

Above: A typical armed trawler – HMT John Edmund.

U-40 and U-23 were sunk in June and July 1915 respectively by trawlers working in tandem with submarines.

During 1915, 29 Q ships entered service comprising a variety of steamships, fishing vessels and sailing ships. The ideal Q ship was one that was capable of disguise, with no peculiar structures. Given their intended tactics, the size of the vessel was also important – if it were too large, it might simply be torpedoed, whereas with a smaller vessel but yet of sufficient size to be attractive ‘bait’, a U boat might not wish to expend one of its few torpedoes. A ‘tramp’ steamer - small and ordinary - was particularly suitable. The ability to change appearance was also important, particularly as Q Ships would ply back and forth on normal trade routes in the hope of attracting attention from any lurking U boats. The holds would often be filled with timber to keep them afloat in the event of being torpedoed.

But it also had to be run as a mercantile ship and in mercantile fashion. Uniforms were forbidden – even down to Navy issued flannel underwear, which if seen hanging on the washing line on board, would have given the game away. The Admiralty provided a small allowance to each man for the purchase of suitable clothing.

One of the first Q ships – Loderer (later to become HMS Farnborough)– was a filthy collier. After being thoroughly cleaned up and painted, she would carry three 12-pounder guns, one 18-hundredweight and two 12-hundredweight, and a Maxim gun. These were variously concealed under false housings, with hinged sides, dummy lifeboats, empty cargo crates etc.

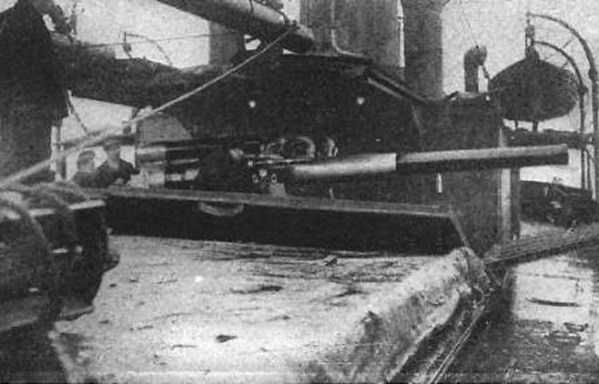

Above: An example of the concealment of a Q Ship’s weaponry

Initially, the Navy considered that an ideal Q ship’s company would be drawn from the Navy’s hardmen – such as leave breakers, brawlers – but in reality the crew members of a decoy ship needed to be well disciplined. Crew numbers were larger than when on ‘normal duty’ as the crew manning the hidden guns often had to stay hidden in complete silence during what would become the pantomime act of the Q ship.

The tactics were simple. When the Q Ship had attracted the attention of a submarine, the ‘crew’ would launch a boat to indicate that they were abandoning the ship, in the hope that the submarine would approach the ship whilst the Navy gunners and the Captain would remain hidden in their concealed positions. The ‘panic party’ as this process became known evolved into a more intricate and ostentatious pantomime as the war progressed with displays of confusion as men sought to get into lifeboats. The lowering of the lifeboats was often done clumsily so that one of the boats came down ‘end up’. Other sideshows developed as crews polished their acts – with the crowning glory being the evacuation of a large stuffed parrot in a cage. If the deception worked and the U Boat approached the ship, the Captain would ensure that the White Ensign was raised as the bogus fittings fell down to expose the guns.

Above: A cigarette card depicting a Q Ship

It was no simple matter for a Q Ship to sink a U Boat with shellfire. The conning tower of the U Boat, whilst a relatively easy target, was not integral to its survival. What was required was that the hull and ballast tanks were hit, although much of the hull would be below the waterline.

The first success of a Q Ship would not be registered until 24 July 1915 by the Prince Charles, with Lieutenant William Mark-Wardlaw in command.U-36 was destroyed by the Prince Charles, and the crew taken prisoner. Mark-Wardlaw was awarded the DSC, later upgraded to the DSO, and two of the crew were awarded the DSM. The sum of £1,000 was awarded to be shared among the crew.

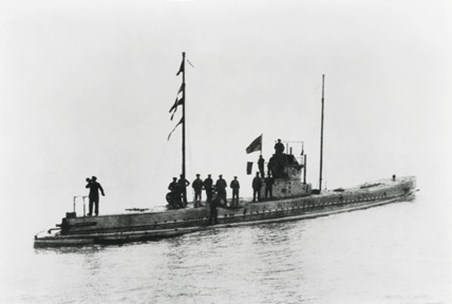

Above: U-36

The reputation of the Q Ships would take a knock later in 1915 with what is referred to as ’the Baralong incident’. The Baralong had been in service as a Q Ship for some months, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Godfrey Herbert. She had been one of the many ships who rushed to the assistance of the liner Lusitania when it was torpedoed and sunk on 7 May 1915. Herbert has been described as a bit of a ‘maverick’ with little regard for strict maritime protocol. The crew of the Baralong were not well disciplined and both Herbert and the crew were becoming frustrated by their lack of success in inflicting damage on the enemy. On 19 August 1915, Baralong received a distress call from SS Arabic which had been attacked by a U-boat. She was also calling for assistance for the freighter Dunsley which had also been torpedoed. Herbert raced to the scene as best he could, but the wrong position had been sent out by the Arabic’s wireless operator. The Baralong returned to its usual route and later that day, a second SOS message was received from the Nicosian only 20 miles away. U-27had just ordered the Captain of the Nicosian to ‘abandon ship’ when the Baralong arrived on the scene, flying the Stars and Stripes.

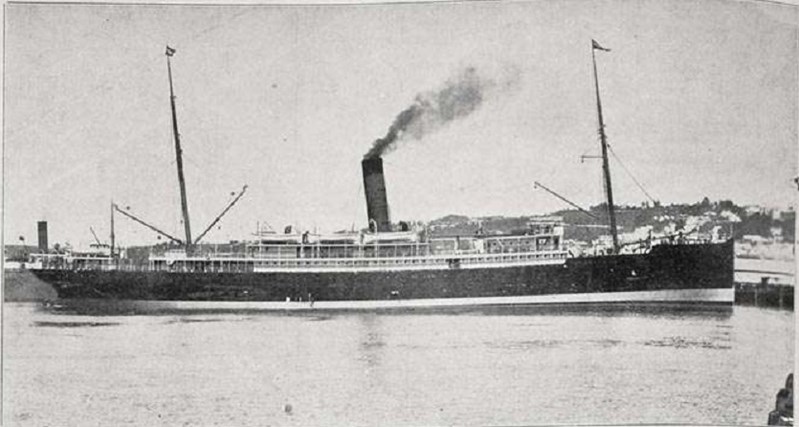

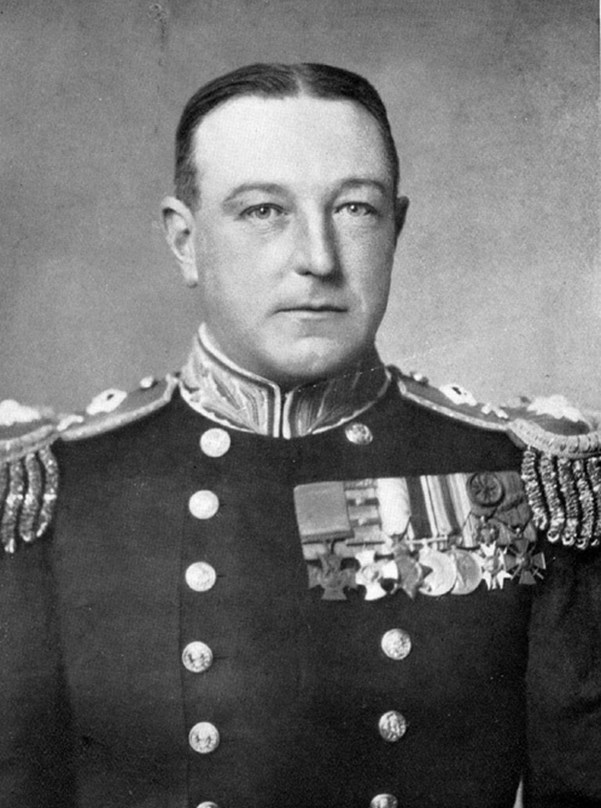

Above: The Baralong and its commander, Godfrey Herbert

Baralong fired on U-27 which sank, with survivors heading for the Nicosian which despite being hit by U-27 had not sunk. The Germans who had managed to get onto the Nicosian would lose their lives in circumstances that were far from unclear. The German Government accused Herbert of ‘cowardly murder’ and demanded that he be tried for murder. More scandal followed the Baralong, later being accused of running down a lifeboat of Germans in September 1915.

One of the repercussions of the ‘Baralong’ incident was that the ‘mystery’ ships were not as mysterious as the Admiralty would have liked. This coincided with a period when Germany abandoned its unrestricted submarine warfare, largely in the face of protests from the United States. Over the winter of 1915/16 there was little evidence of U-boats in Northern waters and it was not until early 1917 that unrestricted submarine warfare recontinued in an attempt by Germany to cut Britain’s supply lines completely. Despite this, 1916 saw the loss of 11 Q Ships.

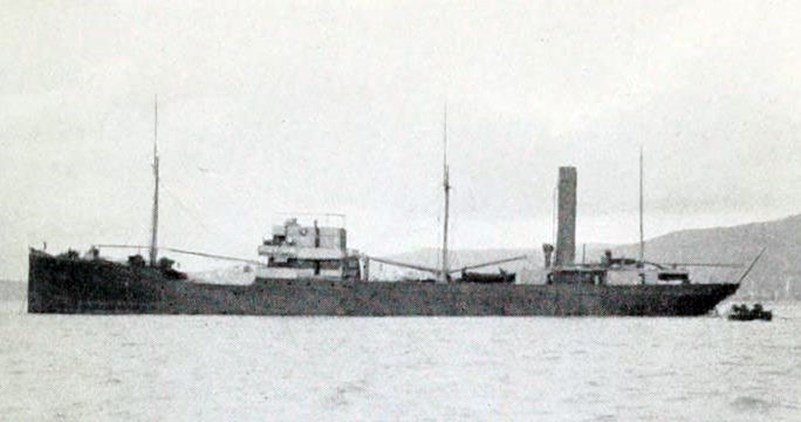

Above – SS Perugia (Q-1), torpedoed and sunk on 3 December 1916 in the Gulf of Genoa

Early 1917 saw increasing U-boat activity and loss of shipping as a result until Britain introduced the convoy system later that year, with the Q Ships registering several victories in the early part of the year, but also suffering losses.

In January 1917, HMS Penshurst (Q-7) accounted for UB-37 in the English Channel.

Above: HMS Penshurst undertaking a training exercise, with the ‘panic’ party rowing away in one of the ship’s boats.

In February 1917, the Farnborough, (Q-5, previously the Loderer) under Commander Campbell sank U-83.The Farnborough, however, had been mortally wounded by the initial torpedo strike. After destroying the secret papers, Campbell sent out a last wireless message:

'Q5 slowly sinking respectfully wishes you goodbye'.

Nearby ships were able to rescue the crew and tow the wreck to shore. A few days later, Campbell would receive the Victoria Cross from the King. A number of the crew also received awards.

Above: The sinking HMS Farnborough, after her victory over U-83.

Above: Gordon Campbell VC, the Commander of the Farnborough.

Above: Captain Campbell, disguised as a mercantile captain, and Farnborough’s officers

But perhaps the most famous of the Q Ship dramas in 1917 was that of HMS Prize.[1]

Above: A painting of HMS Prize. National Maritime Museum

Under its commander, Lieutenant William Sanders, Q-21 set out on its first patrol on 28 April 1917 and was attacked by U-93. The ‘panic party’ departed the ship, leading U-93 to surface and within a few minutes, serious damage had been sustained to her conning tower. Although it was believed that the U-93 had been sunk, it did manage to return home. Meantime HMS Prize had also sustained damage but managed to return to Milford Haven.

Sanders was later awarded the Victoria Cross for the action, announced in the ‘London Gazette’ of 22 June 1917, and was immediately promoted from acting lieutenant to lieutenant-commander, with awards also been awarded to his crew. However, Sanders would not live to wear his VC – HMS Prize, embarked on her final patrol in early August 1917 and was sunk by UB-48 with all hands.

Above: Lieutenant William Sanders VC. Photo – National Maritime Museum

Throughout 1917, the Q Ships had suffered losses as German U Boat commanders became more cautious about approaching vessels. On Christmas Eve 1917, one of the longest serving Q Ships – HMS Penshurst (Q-7) – was sunk in the Irish Sea, although all the crew survived.

The introduction of the convoy system in May 1917 inevitably detracted from the independent role of Q Ships and in 1918, there were only three instances of possible victories for Q Ships – nonetheless, they had played a valuable part in the war at sea, but as their ‘surprise tactics’ became less of ‘a surprise’, their effectiveness waned.

Q Ship tactics would also be employed in the Second World War.

Article by Jill Stewart, Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association

Footnotes

[1] HMS Prize was initially called 'First Prize' as it was the first vessel captured by the British in the war (it was previously called Else). The name First Prize (also Q21) was changed to Prize after her first action in the war

Further reading (WWW)

Q 21 - HMS Prize and William Sanders VC

Further reading (books)

Sea Killers in Disguise Tony Bridgland - 1999

Q Ships and their Story E. Keble Chatterton - 1980