Q-21 - HMS Prize and William Sanders VC

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Q-21 - HMS Prize and William Sanders VC

HMS Prize also Q-21 was previously known as HMS First Prize and originally the German ship Else. She had the distinction of being the first ship captured in the war in August 1914 (hence the name First Prize). Auctioned off by the Admiralty, her new owners, the Marine Navigation Company, later offered her to the Navy for decoy work in November 1916.

Her name would become inextricably linked to that of her Commander – William Sanders.

Above: a cigarette card picture of Lieutenant William Sanders

William Sanders was born in Auckland on 7 February 1883, the son of Edward, a boot maker, and his wife, Emma. On leaving school, he was briefly apprenticed to a mercer before embarking on a seagoing career as a cabin boy on the small coastal steamer Kapanui. He later gained experience on a government steamer before joining the Auckland based Craig Line which operated a fleet of sailing ships trading with Australia. He later joined the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand, becoming third officer on ships that would become troopships after the outbreak of the war.

Above: SS Kapanui, the first vessel on which Sanders would serve

Sanders had applied for the Royal Naval Reserve early in the war but he was not called upon until early 1916 when he was commissioned a sub lieutenant, initially serving on mine sweeping duties. He later volunteered for decoy work with Q Ships, with his experience of sailing ships an attraction, given that a number of the Q Ships were sailing vessels.

Initially he served on the Brigantine conversion Helgoland (Q-17) with Captain Blair, engaging three submarines whilst becalmed and without steerage.

Above: the Helgoland. Photo – paekoroki.tauranga.govt.nz

In February 1917, Sanders, now a Lieutenant, took on the command of HMS Prize, now fitted with three 12-pounders and with 170 tons of copper slag in her bottom as ballast. On 26 April 1917, she left Milford Haven for a cruise off the west coast of Ireland. On 30 April, off the Scillies, the Prize encountered U-93. Under fire, Sanders ordered the ‘panic party’ away in the boats, whilst others remained concealed, although several of these men were wounded. U-93, under Kapitanleutnant Freiherr Speigel, drew closer to Prize– Speigel would later state that he had no reason to suspect he was being decoyed. At the critical moment, and after an agonising wait, Sanders gave the order – the White Ensign was raised and the flaps concealing the hidden guns fell down. No fewer than thirty six 12-pounder shells blasted at U-93, which sustained severe damage to its conning tower and hull.

Above: a watercolour by Charles Edward Dixon depicting the action. National Maritime Museum Greenwhich

The ‘panic party’ rowed to the spot where U-93 disappeared into a sea mist and picked up three survivors – Spiegel, his navigating officer and a stoker.

According to Chatterton, Spiegel’s words to Sanders on being brought aboard the Prize were:

“The discipline in the German Navy is wonderful, but that your men could have quietly endured our shelling without reply is beyond all belief”.

Meantime, HMS Prize herself was damaged but managed to reach the Irish coast when she was then towed into Kinsale and thence to Milford Haven.

Sanders was awarded the Victoria Cross for his gallantry in this action and was promoted to the temporary rank of Lieutenant Commander. Lieutenant Beaton was awarded the DSO and the rest of the ship’s company awarded the DSM.

Although it was thought that U-93 had sunk, First Leutnant Ziegler managed to nurse the submarine home to Germany on the surface. After a refit, it would finally come to grief on 17 January 1918. But it is quite possible that on his return to Germany, Ziegler would have been able to provide a detailed description of Prizeto his superiors. A further encounter with a submarine on 12 June 1917, when Prize sustained further damage and Sanders was injured, might also suggest that a description of the vessel was being gathered by the Germans.

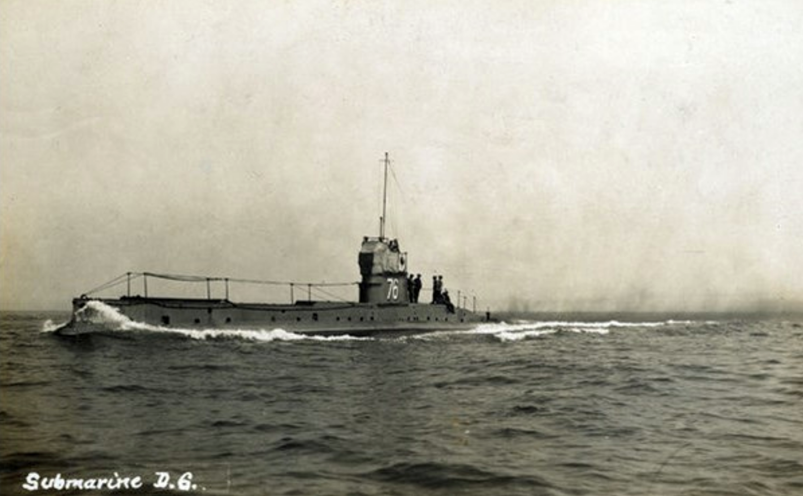

HMS Prize’s last voyage, sailing now under the Swedish flag, would be in tandem with the British submarine D-6 when on 13 August 1917, UB-48 was sighted.

Above: UB-148 – similar to UB-48

Above: the British submarine D-6

Prize opened fire –but UB-48 disappeared. At this point, Sanders probably should have headed home – his disguise was truly ‘blown’. At dawn on 14 August, the crew of D-6 heard an almighty explosion – there was subsequently no trace of HMS Prize – no wreckage, no bodies, no lifeboats. UB-48 had fired two torpedoes at Prize and William Sanders and 26 members of the RN/RNVR had perished. Sanders’ VC was later presented to his father at Auckland Town Hall in June 1918.

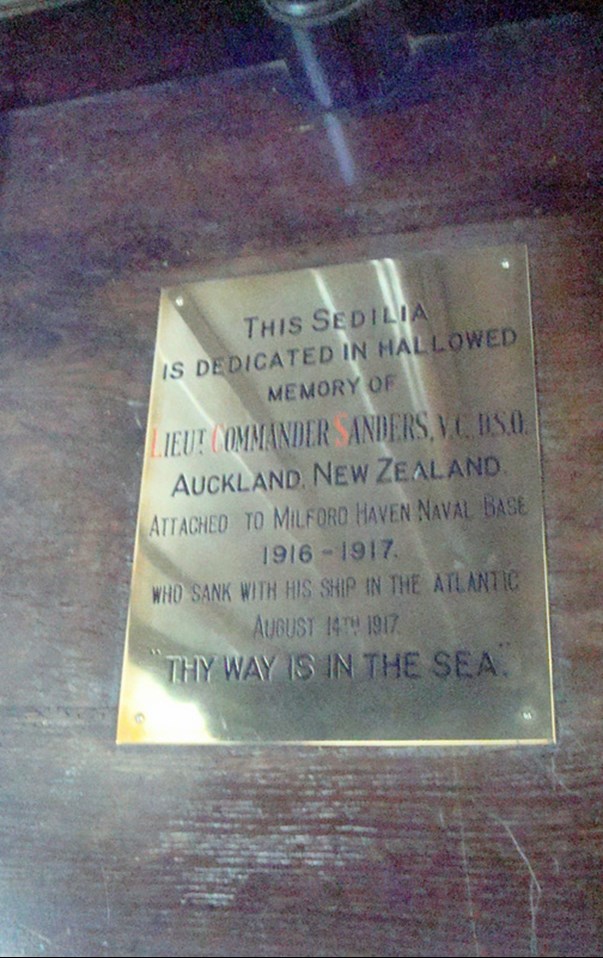

A memorial to William Sanders can be found in St Katherine’s Church in Milford Haven.

Above: the memorial in St Katherine’s Church, Milford Haven

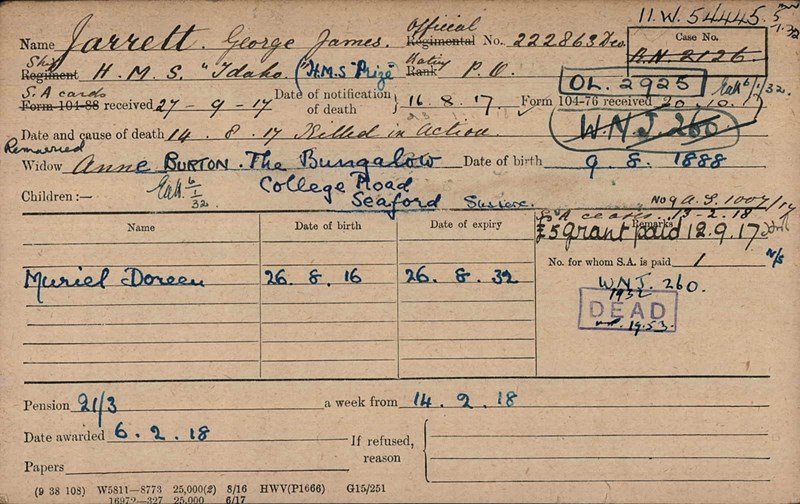

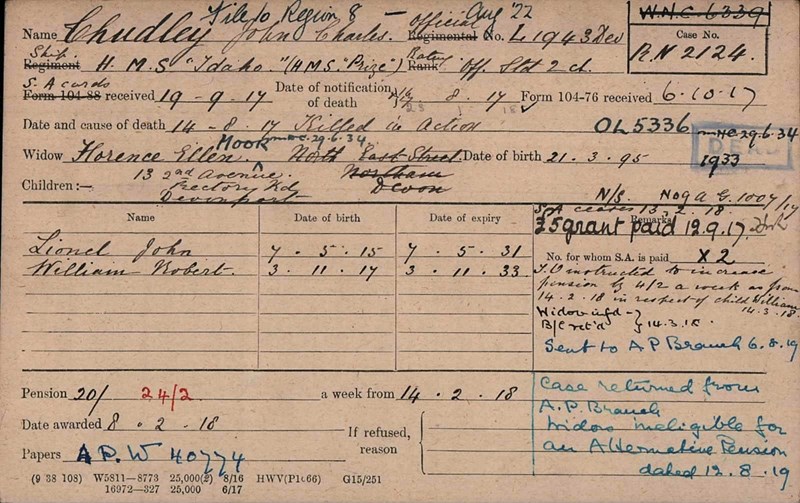

Most of Sander’s crew were new to HMS Prize following her action in April 1917, apart from George James Jarrett and John Charles Chudley.

Above: the Pension cards for George Jarrett and John Chudley

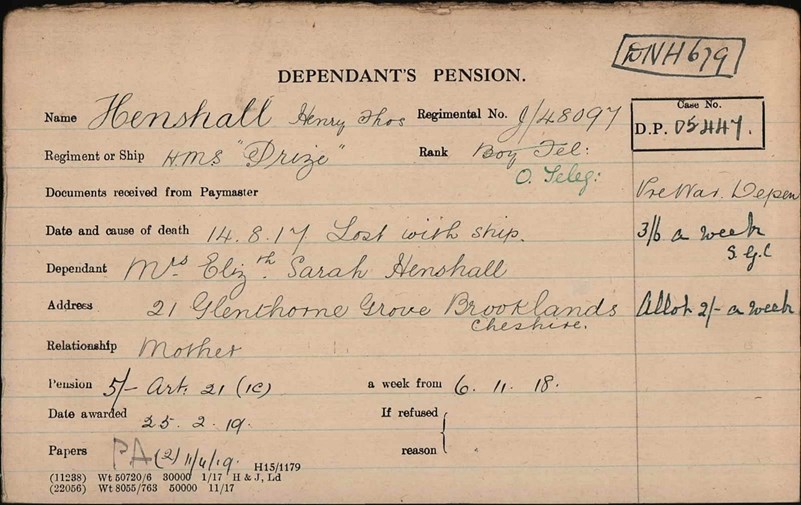

Thomas Henry Henshall had joined Prize only a few days before the vessel was lost. He was born in 1899 in Manchester and had enlisted in November 1915. He had also served on Q-13 earlier in 1917.

Above: the Pension Card for Thomas Henry Henshall

One of those lost on 14 August was Kenneth Norman MacDonald, born in Lochcarron in September 1897. Kenneth had gone to Aberdeen University in 1914 to study Arts, with a view to studying Medicine later, but volunteered for the Navy as soon as he reached military age.

Above: Kenneth Norman MacDonald. Photo – University of Aberdeen

Those lost from HMS Prize are commemorated on memorials in Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth.

Above: the Portsmouth Naval Memorial. Photo - CWGC

Article by Jill Stewart. Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association

Further reading (WWW)

Pantomime at sea: Q-ships in WW1 | The Western Front Association

U-36 and the Prince Charles | The Western Front Association

Further reading (books)

Sea Killers in Disguise – Tony Bridgland - 1999

Q Ships and their Story – E. Keble Chatterton - 1980