Private Alfred Berry and the Zeebrugge Raid 1918

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Private Alfred Berry and the Zeebrugge Raid 1918

The Zeebrugge Raid of St. George’s Day 1918 was an audacious attempt by the Royal Navy to neutralise the activities of the German U-boats that were intent on bringing Britain and her allies to their knees. They were creating havoc in the English Channel, at least a third of allied shipping carrying food, munitions and other equipment – amounting to some 2,554 vessels – had been sunk. Crucial to the operational effectiveness of the German submarine fleet was the canal system that linked Zeebrugge to Bruges eight miles inland; it was a safe haven and a vitally important strategic base.

The raid itself can be seen as a precursor to amphibious operations carried out during the Second World War such as those at St Nazaire and Dieppe. It was a collective act of bravery by the men of the Royal Marines and the Royal Navy that has seldom been equalled, but a costly escapade that resulted in heavy casualties estimated at 227 dead, 377 wounded, and 19 taken prisoner of war, and borne to a large extent by the 4th battalion of the Royal Marine Light Infantry (RMLI), of whom 119 men died from a total casualty figure of 366 out of 730 men. One of those that lost his life was Private PO/18840 Alfred Ronald Berry.

Alfred Ronald Berry was born on 21 April 1898 the son of Charles James Berry, a tin and coppersmith, and his wife Anne (née Dadswell) in Uckfield, a small market town in East Sussex, that had grown around a settlement dating back to at least the mediaeval period. At the time of the 1901 census, Alfred lived at Rock Hall Cottages, towards the north end of the town with his parents, older sister Florence, and his cousin Mabel Russell.

Above: Uckfield High Street (image: Sussex Forge.com)

A decade later, aged 12, he was living at 20 Victoria Cottages, Alexandra Road, in New Town, a development immediately to the south of the River Uck that had proliferated upon the coming of the railway in 1858, with his parents and infant brother George William Berry. His father was plying his trade as a tinsmith at home; the 1911 census shows his employment status as 'Own Account’, i.e. self-employed.

When Alfred came of working age, he secured employment as a greengrocer’s assistant. By this time, the family had moved to 78 New Alexandra Road in New Town. A small Victorian terraced cottage, it is a stone’s throw from the railway line, and the passage of days was marked by the regular arrivals and departures from Uckfield station nearby. From his back garden Alfred could hear the down train from Tunbridge Wells on its approach to the station well before he saw it. Rounding the sweeping curve from Buxted hidden from view in the cutting, the warning toot of the whistle and the rhythmic blowing of the steam engine heralded its appearance. As it passed the house, a grinding and screeching of brakes signalled that it was nearing the station, followed by a final prolonged exhalation of steam after coming to a halt. These were the familiar sounds of home that Alfred took with him when he left to enlist with the RMLI at Brighton on 23 August 1915. He was 17 years old.

Above: Uckfield Railway Station (image: Uckfield News.com)

Above: Uckfield Railway Station (image: Uckfield News.com)

He completed his basic training at the Recruiting Depot at Deal before being transferred to ‘B’ company Portsmouth Division, on 24 February 1916. At that time the rank and file in the Royal Marines were still known as Privates in the RMLI and Gunners in the Royal Marine Artillery (RMA) in line with their army counterparts. It wasn’t until 1923 when the Corps was reformed and the two arms were merged that the rank of Marine was assumed. [1]

Above: Royal Marines Depot, Deal (image: British Listed Buildings.co.uk)

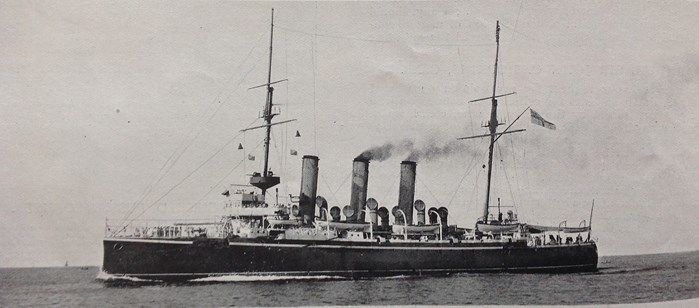

From late September 1916 to 12 December 1917, Alfred was posted to HMS Vindictive; an aging cruiser launched in 1897. On 5 October 1916 the Vindictive set sail for Russia via Busta Voe in the Shetlands, arriving at Murmansk on 14 October 1916, thereafter serving in the White Sea, operating out of Murmansk, Yukanskie (otherwise known as Gremikha and Ostrovnoy) and Arkhangelsk, before returning home in late 1917.

Above; HMS Vindictive in 1900 (wikipedia)

On 23 February 1918, Alfred’s ‘B’ company reported to Deal, where they joined ‘C’ company Plymouth Division, who had arrived the day before. On the 25th, ‘A’ company Chatham Division also joined them, the three companies forming the 4th Battalion RMLI. Training commenced for the raid, although the true details were kept secret from the men – they were under the impression that they would be assaulting a dry canal in France. An intense course of physical training ensued, including night training involving smoke, flares, Very lights, rockets and dummy bombs.

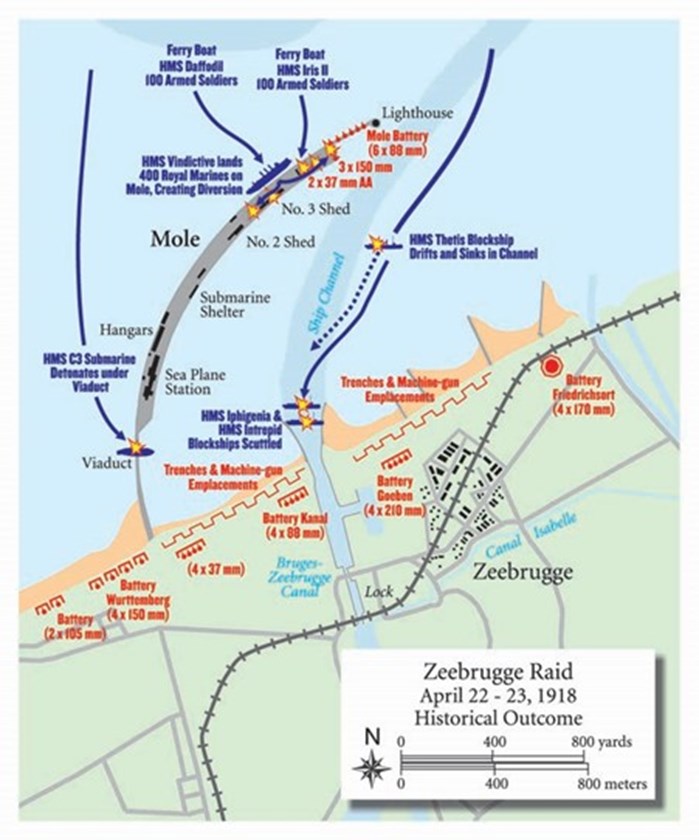

The marines were to form a raiding force, augmented by sailors who had served with the Royal Naval Reserve earlier in the war in the trenches, in attacking gun emplacements on the Mole at Zeebrugge to facilitate the manoeuvring of three blocking ships – HMS Thetis, Intrepid and Iphigenia; obsolete light cruisers filled with concrete – into the canal entrance where they would be scuttled thereby severely disrupting U boat operations. Simultaneously, the alternative coastal route to Bruges at Ostend would be blocked.

The Zeebrugge Mole, a one and a half mile sweeping concrete seawall or pier, projected from the Belgian coast northwards, curving through an arc of approximately 90 degrees, until the seaward point faced east. In peacetime the Mole allowed deep-hulled ships to dock at the port without the risk of grounding in the shallower waters nearer the shore. Surmounted by a lighthouse at its tip, adjacent to this was a concentrated battery of guns that would be assaulted by the raiding party to enable the blocking ships to gain access to the canal entrance. The landward end of the concrete Mole was connected to the coast by a short wooden viaduct. In order to prevent German reinforcements from the mainland, two obsolete submarines, C1 and C3, packed with explosive, were detailed to demolish the viaduct by ramming it, whence the crews would set timed fuses before making their exit in motor launches.

A full-scale version of the Mole was taped out on chalk grassland at Freedown between Deal and Dover, where the marines practised over and over – under different scenarios – the storming of the gun emplacements. The men were being drilled in the rudiments of what would become commando-style training, including bayonet and ‘trench’ fighting. Instruction was given in disarming sentries and hand-to-hand combat reinforced by boxing and wrestling and each company included trained Lewis gunners and bombers, adept at throwing Mills Grenades. The Adjutant General of the Royal Marines visited during training and offered those who wished to withdraw from the expedition the opportunity to do so, and even though it was generally understood that this was a suicide mission, ‘Nobody accepted the offer, so in effect every man in the battalion was a volunteer’. [2] After weeks of training, the men were in prime condition and the battalion was combat-ready.

The battalion left Deal by train on 6 April, arriving at Dover from where they embarked and sailed around the Kent coast to board vessels moored in the Swin, a channel in the Thames estuary, where the flotilla was assembling for the raid. One of the ships was very familiar to Alfred, none other than the Vindictive, which had been especially adapted for the expedition, with extra armaments fitted on her port side including flamethrowers, howitzers, mortars and machine guns, and fourteen pulley-operated gangways or ramps – referred to as ‘brows’ – for the raiding party to storm the Mole in force. Alfred must have greeted her like an old friend when he boarded the Vindictive along with the rest of ‘B’ company, composed of four platoons numbered 5, 6, 7 and 8, and accompanied by ‘C’ company, consisting of 9, 10, 11 and 12 Platoons. ‘A’ company were accommodated on a shallow-hulled ferry Iris, which, along with her sister Daffodil, was to be towed across the channel. The Daffodil was to be deployed at an angle to the Vindictive upon arrival at Zeebrugge, her bow to the cruiser’s starboard, steadying her against the mole. The tides and wind direction would determine the timing of the raid, and two aborted attempts were made between 9 and 11 April: adverse weather conditions and rough seas causing the postponement. The wind direction in particular was crucial; a planned smokescreen was vital to the success of the operation. The next date when conditions were favourable was 22 April.

Above: Iris and Daffodil. (Image: Sussex History.net)

Private Philip Hodgson RMLI, of No 12 Platoon, C Company, describes their departure at 2pm that day:

It was a fine spring afternoon, when we set off, Vindictive with Iris and Daffodil in tow to save their limited supply of fuel followed in line ahead by the old gun boats, to become block-ships, Thetis, Iphigenia and Intrepid sailing down outside the Goodwins to our rendezvous off Dover with the remainder of the attacking force consisting of lines of destroyers and MLs with their special smoke generators. It was indeed a thrilling sight to see this armada of ships sailing in perfect order in an almost calm sea as the sun set and darkness fell. [3]

Private Alfred Hutchinson RMLI of A Company was aboard Iris and had an altogether different impression:

The old and ugly Vindictive was ahead. It looked like a giant beetle with fourteen legs. The legs were the landing brows to be used in the Mole. [4]

One of Alfred’s colleagues from B Company, Private James Feeney RMLI, of No 7 Platoon, was understandably sceptical that the raid would take place after the previous attempts were called off:

Stunt to come off tonight. Stowed hammock, packed up our packs, and went on board the Vindictive. We brought our dinners with us, cooked in the mess-tins; also all the bread, sugar and tea we had in the mess. We are doubtful that it will come off, but we all hope that it will. We have taken up our stations and had tea, and we are on the way to the Mole. Everything seems certain as the wind is holding favourable. I do wish that it comes off, as the suspense is awful. At 7pm I can count 57 vessels all going the same way home. We get tea at 8pm, and are to get our usual rum ration at 10pm. If the wind is right at 10.30pm we are to see it through tonight, no matter what happens. Going down now for a short sleep before the landing starts. I hope it won’t be my last short one on this planet. All the boys are quite pleased now that it is to take place tonight. I hope we make a good show and have a decent slice of luck. It would be rotten to strike a mine, or have a collision with another of our ships. This finishes before the ‘Scrap’. I hope I shall be able to finish about the battle. [5]

As the flotilla closed in on Zeebrugge, at 10.40pm, the discharge of the smokescreen began and action stations were signalled at 11pm, an hour before their scheduled arrival. The smoke completely concealed the vessels on their approach, but signalled to the Germans on the Mole that something was up. The sky lit up with searchlight beams and flares as they desperately attempted to identify the threat from the sea, but to no avail, the artificial fog was impenetrable. As the raiders neared their target, the defenders launched powerful star shells, but even as they burst showering light from above, they failed to illuminate the scenario before them, creating a nebulous glow at best. The Vindictive managed to get to within a few hundred yards of the Mole when the wind suddenly changed direction and the German gunners finally had sight of their target; all hell was let loose.

Above: Vindictive alongside the Mole. (Image: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Sergeant Harry Wright RMLI of No 10 Platoon, C Company, describes the first direct hit:

Then the silence was broken by a terrific report, followed by a crash as the fragments of shell fell among us, killing and maiming the brave fellows as they stood to their arms, crowded together as thick as bees. The Mole was just in sight; we could see it off our port quarter. Our gunners replied to the fire but could not silence that terrible battery of five-inch guns, now firing into our ship at a range of less than a hundred yards from behind the concrete walls. A very powerful searchlight was now turned on us from the sand dunes at Zeebrugge, and the powerful batteries there began to fire. The slaughter was terrible. [6]

Private Bill Scorey RMLI, of No 5 Platoon, another of Alfred’s colleagues from B Company:

…How I escaped God knows, for the first shell that hit the Vindictive, which our Coy was on, killed dozens and set them all aflame, all the lads round me were blown to bits and I was flung between her funnels, my tin hat was shattered and so was my rifle, but I soon found some more. We then had the order, ‘Steady Pompey Company’. We were just going alongside the Mole, our section was the first to land, what there was left of us, and we were very lucky too, for no sooner were we on top of the wall, than the German machine gunners had the range, and were playing hell with us, then the heavy guns fired point blank into us, but we still advanced and soon silenced them. [7]

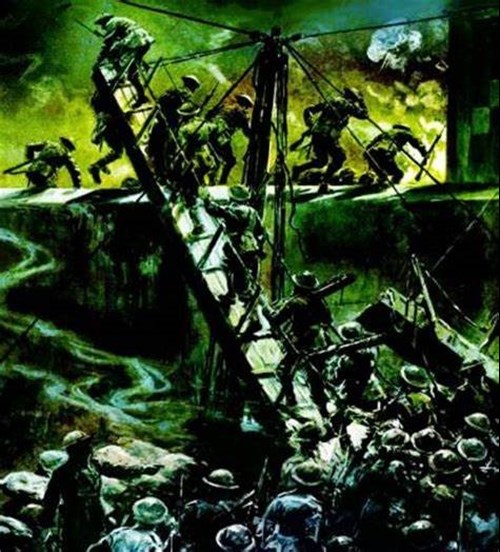

Above: Artist's impression of the RMLI landing from HMS Vindictive (Image: Royal Marines History.com)

The Vindictive had gone full steam ahead to evade the shellfire and in the fog of war had overshot the planned berthing by about 300 to 400 yards, nearer the landward point of the Mole and further away from their main objective, the battery of guns, leaving the marines to negotiate a much greater distance under fire with little or no cover. ‘C’ Company, having drawn lots beforehand, had won the honour of leading the storming of the mole, but such were their losses from the initial German bombardment that No 5 Platoon of ‘B’ Company had to take their place. The landing was made even more challenging by the loss or damage of most of the gangways or ‘brows’. German shell and gunfire had rendered all but two useless, but this pair was put to good use; No 5 Platoon disembarked and swiftly dealt with a team of snipers, who otherwise would have picked off the raiders one by one. Sailors with their own allotted tasks, including demolition, and the remnants of ‘C’ Company’s No 9 and 10 Platoons (of 45 men of No 10 Platoon only 12 were still standing, with No 9 suffering similar losses) followed. Then came No 7 Platoon, as recounted by Private James Feeney RMLI:

We got down two gangways, and Plymouth section went over before us. The sailors were going over individually before that. Sgt Brady gave us the order to go up and over. The fire main had been perforated by shrapnel and we had to pass under it. We got something to keep us cool; down my back I got a shower. The sergeant stood very near it. He was trying to hide the bodies of three of the pom-pom gun’s crew from us when we got on a level with the hinge of our gangway. The battalion Sergeant Major and the adjutant were superintending the getting over of the ladders. Well, it was not like anything I ever saw on parade, except that these two were just as cool. I offered to give a hand with the ladders when I was passing up the gangway, but Sergeant Major told me to go over. [8]

Above: Artist's impression of the RMLI storming the Mole. (Image: Warfare Magazine.com)

As the Vindictive had berthed nearer the shore than was originally intended, the first objective of capturing an anti-aircraft gun, prior to demolishing a structure on the Mole, known as No.3 shed, and dealing with any German defenders within, had to be modified. Private Feeney describes what happened next:

I ran across to the dump-house [No.3 shed] opposite the ship, and took cover by lying on the ground. The ground floor of the dump-house was raised about two and a half feet over the roadway, and had a pathway like as if carts were loaded there, like at a railway goods store. We had a grand chance of chucking bombs in the doors of this dump-house, as we had splendid cover. Whilst amusing myself here, a portion of concrete was removed out of the Mole by the explosion of the submarine [C3] that was stuck in the piles. I could not attempt to describe what this operation sounded like. It was about the very last word in noise. When we got back we were told that the dump-house was to be blown up now, so we went away on the left, and I could see no one to fire at. [9]

Above: Artist’s impression of the Zeebrugge Mole showing the actual position of HMS Vindictive, the Daffodil holding her steady, juxtaposed with the planned position nearer the gun emplacements at the Mole’s seaward point, with the three blocking ships entering the harbour. (Image: Forces.net)

‘C’ Company encountered the crew of a German destroyer moored parallel to the Vindictive on the inner side of the mole; an unnamed officer takes up the story:

Three German destroyers lay alongside the other side of the Mole, and all three of them kept firing at Vindictive at close range. From these destroyers a number of German sailors swarmed up to attack us, but they found themselves face to face with British bayonets, and with a shout our men charged them. This was more than Fritz could stand. Clearing a space, we dashed to the first vessel into which we threw some fifty hand-bombs. A loud explosion followed, and the last we saw of the destroyer was that she was on fire and sinking. [10]

The unidentified officer recounts what happened next:

After bombing and setting alight the destroyer, we formed up and forced our way ashore at the point of the bayonet. We charged the gun crews on the beach which had been giving us so much trouble, and after killing a number dispersed the rest and captured the guns. All around us we could hear the noise of the conflict, the cries and shrieks of the dying and wounded. It was horrible, but our men behaved magnificently. [11]

An unnamed marine corroborates the officer’s account:

We then received the order to charge, and we rushed along the Mole to the shore. We bayoneted and shot all the men we came across. The noise of the firing intermingled with the shouts and cries of the men was terrible. It was a fair slaughter, and all around us was hubbubs; but we kept our heads, and put the wind up the Boche completely. [12]

The marines, enraged by the slaughter of their pals whilst preparing to land, were involved in some savage close-quarter exchanges. Private Warren from ‘B’ Company, No 8 Platoon, witnessed an extraordinary sight:

I saw one of our fellows toss one of the enemy over his head, as he could not withdraw his bayonet. [13]

Above: Artist’s impression of the Mole with No 3 shed on the right and the shell-holed funnels of HMS Vindictive towering over the seawall to the left. (Image: Royal Navy)

‘B’ Company, now reduced to 16 men from No 5, 7 and 8 Platoons, assembled for the planned assault on the battery of guns at the seaward end of the Mole, the main objective of the RMLI. Private James Feeney describes the composure of Captain Bamford, CO of Alfred’s ‘B’ Company:

Captain Bamford came up and said, quite cool, ‘Fall in, B Company.’ I fell in with McDowell, and Sergeant Brady took charge of us. There were only 16 there, and Captain Bamford was leading us along…[14]

Above: Detailed map of raid. (Image: Martinus Evers.org)

The remnants of ‘B’ Company launched their charge, totally exposed to enemy fire on the Mole, but no sooner had this daring dash begun than Bamford gave the order to retire. The signal of the ship’s siren had sounded ordering the ‘general Recall’.

Private Bill Scorey RMLI, No 5 Platoon:

We then had the order to retire, but the devils started to come on the wall at us, but few got away. One fired point blank with his revolver at one of our lads, but he paid dearly for it, for our Captain (Bamford) crowned him with his loaded stick [...] We then had to come aboard owing to the tide, but had to climb up the wall again by ladders, which was about 15 to 20 feet high so it was no easy job. No sooner were we on the top than a shrapnel shell came and scattered us, some got blown back on the Mole and some in the water. I went in the water myself, but managed to get on board by a rope, which was flung to me, she then pushed off leaving some men behind. I think I was the last man aboard. [15]

At some point during the raid, Alfred had been seriously wounded. But the marines were determined not to leave any of their pals at the mercy of the Germans. There were many acts of selflessness carried out in the withdrawal; Private Warren told a journalist that ‘Many of the wounded owe their lives to their comrades who carried them off’. [16]

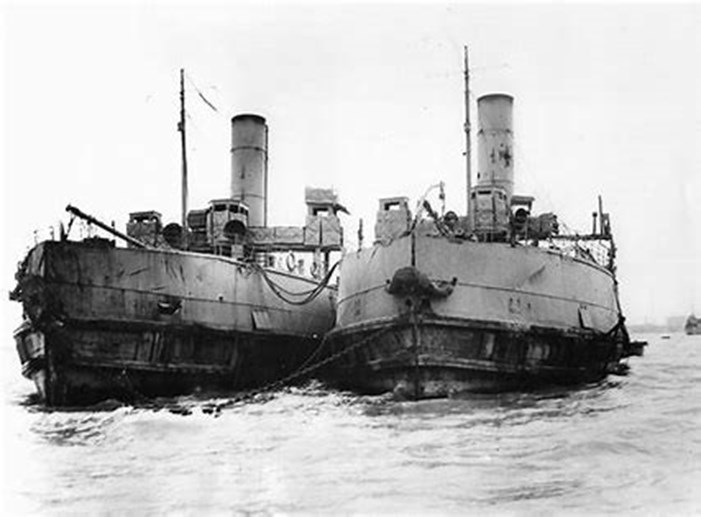

It was 12.50am; the RMLI had been fighting on the Mole for around three-quarters of an hour when the raid was brought to a premature end, the deadline was 01.20am due to the tide and ‘Daffodil’s siren sounded the recall thirty minutes early’. [17] The marines were unaware that the blocking ships had already successfully navigated the threat from the German guns and had reached the canal entrance, with the exception of the Thetis, which had run aground short of the target after experiencing engine problems. The charges on the Thetis were fired nevertheless, scuttling the ship. The Iphigenia and Intrepid reached their objective and were both sunk likewise, albeit not completely blocking the canal. And as Private Feeney noted, Submarine C3 had also achieved its objective, destroying the wooden viaduct at the landward end of the mole.

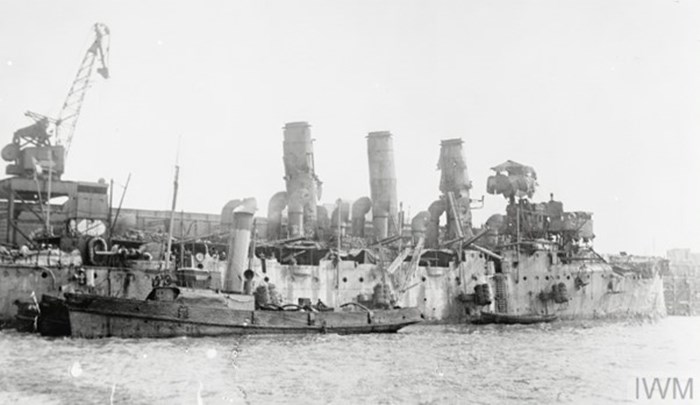

Above: The blocking ships at the mouth of the canal, HMS Thetis furthest from the camera, the Mole in the background. (Image: IWM.org.uk)

Private James Feeney RMLI, No 7 Platoon:

Then we saw the cost of our landing, one thing was evident – it cost a great deal of blood. I shall never forget the sight of the mess-decks: dead and dying lying on the decks and tables where, but a few hours before, they ate, drank and played cards. In the light of day it was a shambles. The admiral’s flagship passed and greeted us warmly. We never got our rum ration that morning, although I got a mouthful of ‘neat’ about 2.30am from an officer who was doing the good Samaritan with a jug in one hand and the nickel-plated end of a half-pint flask in the other. We had all the bodies collected up together at one end of the ship. I had a last look at Corporal Smith and Rolfe (Private Frank Rolfe RMLI, aged 19). [18]

Captain Bamford was feeling despondent as the Vindictive sailed towards home, he considered the RMLI to have failed in their main objective of neutralising the battery of guns at the seaward end of the mole, although their task had been hampered from the point when they had disembarked, having berthed 300-400 yards further away from the intended landing point. However, there is no doubt that they had caused such a diversion that the blocking ships were able to enter the harbour and run the gauntlet of the German guns relatively unscathed, and achieve the primary objective of the raid, that of obstructing the canal entrance.

Above: HMS Vindictive on her return from Zeebrugge: port side showing fenders. (Image: IWM.org.uk)

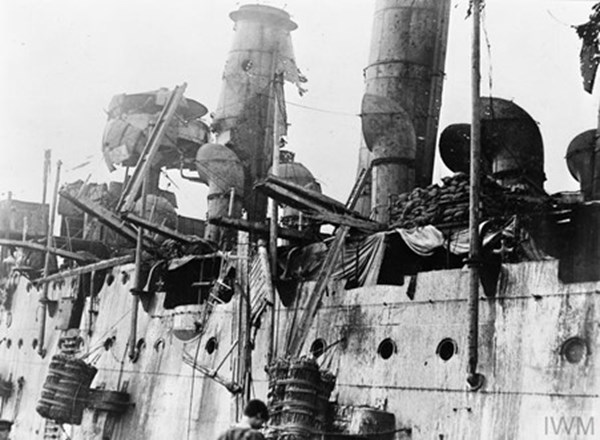

Above: Close-up of the shell-damaged HMS Vindictive port side showing the broken and battered ‘brows’. (Image: IWM.org.uk)

Captain Edward Bamford was awarded the Victoria Cross, the officers and men of the 4th Battalion having nominated him by ballot, a process undertaken whereby a whole unit was deemed to have acted with such outstanding courage that individuals could not be singled out and it was left to that unit to select two of their number to be the recipients. Sergeant Norman Finch of the RMA was the other VC recipient from the corps, who continued firing his naval pom-pom gun from the Vindictive’s foretop even though badly wounded, and the whole of the rest of his crew having been wiped out.

Above: Captain Edward Bamford, VC, DSO, of ‘B’ Company RMLI. (Image: Royal Navy)

Above: Sergeant Norman Finch VC, RMA. (Image: Memorials in Portsmouth.co.uk)

Upon arrival at Dover, an ambulance train was waiting at the station platform to take the seriously wounded, numbering 130 men, to the Royal Naval Hospital, Chatham. The following day, 24 April, King George V visited the hospital and spoke to many of the men. The day after that, barely out of his teens – he had turned 20 on the eve of the raid – Alfred Berry died of his wounds. He came home to Uckfield and was laid to rest in the town’s cemetery at Snatts Road.

Above: Royal Naval Hospital, Chatham. (Image: IWM.org)

The Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, described the Zeebrugge Raid as ‘one of the most gallant and spectacular achievements of the War’ [19]. Winston Churchill thought ‘it may well rank as the finest feat of arms in the Great War, and certainly as an episode unsurpassed in the history of the Royal Navy. The harbour was completely blocked for about three weeks and was dangerous to U-boats for a period of two months. Although the Germans by strenuous efforts partially cleared the entrance after some weeks for U-boats, no operations of any importance were ever again carried out by the Flanders destroyers’.[20]

The question of the success or otherwise of the Zeebrugge Raid is a moot point; objectively, it can only be counted as a partial success, albeit a valiant one. The positioning of the scuttled Iphigenia and Intrepid had not been precise enough to seal the canal. However, at least initially, German vessels were unable to negotiate the canal entrance at all at low tide, and with some difficulty at high tide. Substantial dredging work had to be carried out to clear a passage alongside the sunken cruisers. Thus it can be said that U-boat operations had been disrupted to an extent.

What is not in question is the bravery and fortitude displayed by Private Alfred Berry and all of the men of the 4th Battalion, RMLI. They knew of the mortal danger they were in, each and every one, but did their duty nonetheless. The last word should be left to Leading Stoker Henry Baker of the Royal Navy, who told reporters at Dover after the raid:

…if you have the power of the pen, say all the good things you can about those Marines. They worked with a precision and a contempt for danger in a manner that I shall never forget. Although young in years I have had some experiences, but never anything to touch these brave Marines. They just had certain allotted work to do. They did it even unto death. [21]

Above: Alfred Ronald Berry’s headstone. Photo – Paul Blumsom

Article by Paul Blumsom

References:

- No 32871 The London Gazette (Supplement) 16 October 1923 p.6961.

- Thompson, Julian, The Imperial War Museum Book of The War At Sea 1914-1918, Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 2005, p.406.

- Kendall, Paul, Voices from the Past: The Zeebrugge Raid 1918, Frontline Books, Barnsley, 2016, pp.69-70.

- Arthur, Max, The True Glory: The Royal Navy 1914-1939, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1996, pp.124-5.

- Holloway, Susan, From Trench and Turret: Royal Marines’ Letters and Diaries 1914-18, Constable, London, 2006, p.163.

- Kendall, p.86.

- Holloway, p.166.

- Holloway, p.168.

- Holloway, pp.169-70.

- Kendall, p.148.

- Kendall, p.153.

- Kendall, p.154.

- Kendall, p.153.

- Holloway, pp.169-70.

- Holloway, pp.170-1.

- Kendall, p.200.

- Brooks, Richard, The Royal Marines: 1664 to the present, Constable, London, 2002, p.249.

- Holloway, p.172.

- Lloyd George, David, War Memoirs of David Lloyd George, Odhams Press Limited, London, 1938 edition, p.701.

- Churchill, Winston. S., The World Crisis 1911-1918, Odhams Press Limited, London, 1938 edition, p.1242.

- Kendall, p.281.