Private Arthur Gurr and the Battle of Boars Head

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Private Arthur Gurr and the Battle of Boars Head

The sparse beauty of the rolling chalk grassland that is the South Downs has long been celebrated by artists, writers, and musicians. Running from Eastbourne in the east to Winchester in the west, this picturesque range of hills has also been memorably versified by Rudyard Kipling in his poem Sussex:

No tender-hearted garden crowns

No bosomed woods adorn

Our blunt, bow-headed, whale backed downs

But gnarled and writhen thorns [1]

The easternmost section of the Downs, that which runs through the modern-day county of East Sussex, epitomises the landscape referred to by Kipling. Largely bare of trees and thinly populated by scrub, the poet’s stark and rugged description – blunt, bow-headed, and whale backed–incongruously reflects the distinctive nature and aesthetic appeal of this coastal downland.

Above: Sheep grazing on the South Downs (Image – wiredforadventure.com)

For centuries, the Downs have been grazed by livestock, producing a specific breed of small, polled sheep, synonymously named the Southdown. Upon its formation in the Great War, the 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment (1st Southdown Battalion) adopted an orphaned Southdown lamb named Peter as the regimental mascot.

Above: Officers from the Royal Sussex Regiment, including Colonel Claude Lowther seated in the centre with his dog at his feet, and Peter, the orphaned lamb and Battalion Mascot, featuring prominently (Image – caring4sussex.co.uk)

Around four miles north of the South Downs and just over eight miles from Firle Beacon – one of the highest points on the Downs – lies the village of Isfield. The village itself is sited on a flood plain at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Uck; the former cuts through the Downs near Lewes. The countryside surrounding the village is mainly farmland, and the parish church, St. Margaret’s, traditionally serviced the farmworkers and agricultural labourers that lived in the small cottages tied to the estates and smallholdings nearby.

Above: Isfield Village (Image – frankthomas.co.uk)

Above: Isfield Mill (Image – frankthomas.co.uk)

One of these local labourers was 33-year-old Moses Gurr, who married Mary Ann Gorringe, aged 32, on 30 September 1894 at the parish church. The couple began married life in a farm cottage in Buckham Hill, just over two miles north of Isfield village. Seven years later, the 1901 census reveals that Moses and Mary Ann are raising a family: two sons, named Arthur, aged 5, and Harold, aged 2. They also fostered two children, Arthur and Annie Lane, aged 9 and 6, respectively. Moses was employed as a cowman on a local farm. By the time of the 1911 census, Moses has been promoted to farm foreman, and his 15-year-old son Arthur is employed as a domestic gardener, whilst his other boy Harold is still at school. Their foster children, now aged 19 and 16, have left, undoubtedly having secured live-in employment elsewhere.

Above: Buckham Hill, Isfield, where Arthur grew up (Image – pinterest.com)

When war broke out, the MP Claude Lowther, owner of Herstmonceux Castle around 18 miles to the east of Isfield, was eager to serve and/or contribute to the war effort in some capacity. Initially he proposed to raise, equip, and serve with a company of Mounted Infantry (a hangover from the Boer War) before suggesting the founding and funding of a Home Defence Corps, which was formally instituted on 18 August 1914, but out of which evolved the idea of the formation of a battalion of volunteers for active service. This was to be made up of distinct companies from Eastbourne, Hailsham, and Herstmonceux, respectively. Although they would not be generally referred to as such, what he was proposing was the establishment of a ‘Pals battalion’ – groups of local men who lived, worked, and socialised together, thereby drawing on a ready-made esprit de corps.

Above: Claude Lowther (Image – storringtonlhg.org.uk)

Above: Herstmonceux Castle, home of Colonel Claude Lowther (Image – herstmonceuxsussex.com)

Consequently, he applied to Kitchener for permission to raise a battalion of Sussex men. Lowther had military experience; he had served during the Boer War as a Lieutenant with the Imperial Yeomanry and, during the conflict, had been recommended for the award of the Victoria Cross (unsuccessfully) for taking part in the rescue of two wounded men under fire. Kitchener approved his request, and Lowther convened a public meeting at Eastbourne Town Hall, where a recruiting committee was assembled. Lowther’s recruitment drive was a great success; within 56 hours, 1100 men had volunteered, and the 11th Battalion, (1st Southdown Battalion), Royal Sussex Regiment (RSR), was born.

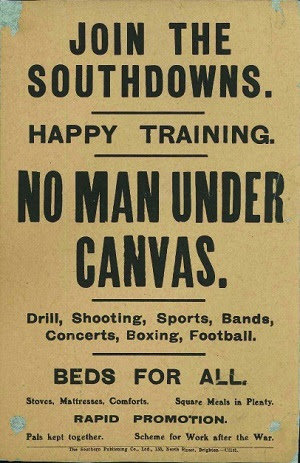

Above: Recruiting poster for the Southdowns Battalions (Image – storringtonlhg.org.uk)

Lowther was helped in this process by the artist Neville Lytton, of Crabbet Park, Worth, near Crawley, who had offered his services as a recruiting agent, driving around Sussex equipped with a pile of attestation papers – often accompanied by a doctor – and being a Justice of the Peace himself, was able to swear the men in, in situ, at their tied cottages and on the landed estates where they toiled. He often met an indifferent, if not hostile, response:

‘I can’t say that I was a very welcome visitor at most of these cottages, but the fact that I was going myself carried a certain amount of conviction. The most irritating people were those who said, “I be’nt going till they Germans come here; then I dare say I shall be as good as some of they”. After about a fortnight’s work I had got together the best part of a company, which was not so bad’ [2].

Above: Self Portrait by Neville Stephen Bulwer-Lytton (Image – jubileegalleries.com)

One of those recruited was Moses Gurr’s son Arthur, who, aged 18, enlisted on 1 September 1914, and was eventually posted to D Company of the battalion. Arthur was a tall lad, a photograph of the company shows that he towered over his fellow recruits, possibly due to his dairy-rich diet throughout childhood: his father’s role as a former cowman and farm foreman would have ensured a plentiful supply, with Arthur’s bones growing long and strong as a result.

Above: D Company, 11th Battalion (1st Southdown) Royal Sussex regiment, Arthur Gurr stands just left of centre in the second row, towering over his colleagues (Image – eastsussexww1.org.uk)

The 11th was formally raised at Bexhill on 7 September 1914, to which Lowther was appointed CO with the temporary rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and training began shortly afterwards at Cooden Camp to the west of Bexhill. Neville Lytton joined the 11th battalion at Cooden, and after a few weeks rigorous training, secured a captain’s commission.

Above: Recruits at Cooden Camp, Sussex (Image – storringtonlhg.org.uk)

Encouraged by his success, Lowther sought permission to recruit a whole brigade of Sussex men, which was granted, and two more battalions were formed, the 12th Battalion RSR (2nd Southdown) on 2 November and the 13th RSR (3rd Southdown) on 20 November. A fourth battalion, the 14th RSR, was eventually formed from depot companies of the 11th, 12th, and 13th as a reserve and training battalion. The three Southdown battalions were dubbed Lowther’s Lambs and would eventually form the 116th Brigade of the 39th Division alongside the 14th Battalion (1st Portsmouth) Hampshire Regiment.

Above: 12th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, 2nd South Downs (Image – armedconflicts.com)

Unfortunately the state of Lowther’s health would prevent him from commanding the brigade on active service, and a serving Brigadier was drafted in; Lytton was not particularly impressed. He observed that ‘Even in those days the battle between the professional and the amateur soldier had begun; each had the heartiest contempt for the other, and to this day I cannot make out which side is most justified in their opinion.’ Lytton was completely underwhelmed by the Brigadier, who, having inspected Lytton’s company upon his arrival at camp, rather than address the men with an inspirational speech acknowledging their sacrifice in volunteering to fight, pulled Lytton to one side and pedantically pointed out that the rank-and-file’s ‘pack straps should be right over left, not left over right’ and told him, ‘See to it another time, will you?’ [3].

Above: Witley Army Camp, Surrey in 1916 (Image – surreyinthegreatwar.org.uk)

Their training continued, moving to Detling near Maidstone in July 1915, then to Aldershot in September the same year, before their final move to Witley in Surrey. Towards the end of their time in Witley, not long before the brigade’s embarkation for France, Lytton clashed with the Brigadier again over a training exercise:

‘A great controversy was raging over a defence scheme of a little hill on Witley Common; the Brigadier, who was just beginning to assimilate the tactics of 1914, was positive that all trenches should be sited on the reverse slope… I remember suggesting that the hill should be tunnelled and that the front line should be on the forward slope, and the support and reserve lines on the reverse slope. This was considered rather impudently precocious, and yet ninety per cent of the hills on the western front were defended in this manner’ [4].

Above: The Embarkation, Southampton, by James McBey (Image – iwm.org.uk)

The 11th RSR marched out of Witley camp at 3:30am on 4 March 1916, eventually arriving at Milford to board three trains bound for Southampton Docks, along with the battalion headquarters staff and the 12th RSR, at 6.00, 7.00, and 7.55am, respectively. The rest of the brigade would embark over the next two days; the 11th battalion was one of the first to leave. Lytton describes their passage and arrival in France the following morning in vivid detail:

‘We reached Southampton by daybreak and hung about there all day; at nightfall we embarked on a horrible little transport called the Viper. The weather was stormy; the men were packed like sardines and were frightfully sick all over each other. We reached Havre at sunrise and formed up on the quay; a very much creased and shop-soiled looking lot we were, and the march discipline from the harbour to the concentration camp was not all that was perfect. The weather was bitter cold and the camp was covered with snow; tents were our only shelter, and we were already chilled to the marrow by the night journey’ [5].

Travelling in such cramped circumstances must have been particularly uncomfortable for Arthur Gurr, his long limbs folded tightly against him during the protracted, overnight crossing.

Above: SS Viper (Image – roll-of-honour.com)

At 3:45am on 6 March, the 11th battalion left the camp and entrained for the front, travelling via Abbeville and St. Pol to Steenbecque, where they detrained and marched to Morbecque and a much-needed rest in billets, along with the rest of the brigade. On 12 March, they went into the trenches at Fleurbaix under instruction. Lytton reports of the battalion’s first casualty:

‘That night one of our men got hit by a stray bullet as he was entering a communication trench, and was killed dead; I had a look at the poor chap as he lay all waxy and white in a destroyed cottage which was used as a mortuary. This was our first man ‘Killed in Action’ [6].

Above: Fleurbaix, France. Soldiers walk along the path beside the row of front line trenches (Image – awm.gov.au)

The following day they were bombarded by 5.9 shells, and Lytton would not escape unscathed:

‘After the burst of one of these shells that had fallen well behind me, I felt something brush my breeches, but in the terror of the moment I paid no attention to it’. He was engaged in dressing the wounds of other casualties when he ‘noticed that my breeks were saturated with blood; I thought at first that it was from the other fellows’ wounds, but as the blood appeared to increase, I stripped and saw that I had two wounds in the right leg’.

Whilst Lytton waited to be medically evacuated, he checked on the casualties and found that there

‘were about nineteen killed; many of them I could only identify by their discs. Some of them were men from our own farms in Sussex whom I had known for years. Poor fellows! All this weary preparation and training and then to be killed without so much as a glimpse at the enemy or even a suspicion of the lustre of their own glory’ [7].

Above: Trench map of Givenchy/Cuinchy (Image – WFA 'TrenchMapper')

On 29 March, having been discharged from hospital, Lytton returned to the battalion whilst they were in billets at Merville. Over the coming months, they were deployed at Givenchy, Festubert, and Cuinchy before taking over the front line at Ferme du Bois trenches near Richebourg l’Avoue on 22 June. Meanwhile, preparations for the upcoming Somme offensive over forty miles to the south were well advanced, with the start date set for 29 June. The overall plan included carrying out as many smaller-scale attacks and raids as possible on other sectors of the front in an effort to deceive the Germans as to the main thrust of the offensive and to occupy the enemy on said sectors and prevent reinforcements on the Somme itself.

Above: Map of the Boars Head near Richebourg l’Avoue (Image – WFA 'TrenchMapper')

Amongst these diversionary attacks, one operation in particular was considered of ‘greater importance than the ordinary raids. This was the suggested capture and retention of a salient in the enemy’s line known as the “Boar’s Head”… which was to be attacked by the 39th Division on June 26th’ [8].

Lytton described this salient as follows:

‘The German line ran out into a sharp point in this sector and almost touched our sap-head; the place was known as the “Boar’s Head.” We were soon informed that we were to attack this “Boar’s Head” and that the main object of our attack was to cause a diversion from the big Somme offensive; a secondary object was to bite off the “Boar’s Head” and “straighten out that bit of the line” [9].

Above: Pre-war postcard of Richebourg-l’Avoue (Image – nl.geneanet.com)

In the event the start of the Battle of the Somme would be postponed by three days to the now infamous date of 1 July 1916. As a consequence the diversionary assault on the Boar’s Head was put back from the 26th to the night of 29/30 June.

On 28 June, the 11th Battalion was relieved from Ferme du Bois and went into billets at Richebourg in preparation for the attack. On 29 June, the three Southdowns’ war diaries detail an artillery bombardment between 2pm and 5:30pm that was intended to cut the German wire and destroy/disrupt their defences. Later that day, the 12th and 13th battalions entered the front line at Ferme du Bois in readiness for the assault. The 11th Battalion, including Arthur Gurr, were detailed as carrying parties for their comrades in the 12th and 13th. The stage was set.

Above: Ferme du Bois later in the War (Image – historiadastransmissoes.wordpress.com)

The 11th’s war diary entry for 30 June briefly refers to the day’s events:

[2:50am] Intense bombardment by our artillery and enemy retaliation. Our carrying parties followed 12th and 13th Battalions to enemy’s front line with RE material and SAA. Casualties: Wounded. Capt. E.G. Cassels, Lt. H.S. Lewis, 2nd Lt. E.B.T. Jones, 2nd Lt. A. Chalk. Missing believed killed. 2nd Lt. F. Grisewood; 2nd Lt. A.C. Cushen. OR approx. Killed 4, Wounded 80, Missing 32. Burial parties and salvage parties for front line[10].

Above: A view from the trenches (Image – storringtonlhg.org.uk)

The 12th Battalion enjoyed some success on the day, at least initially. Their war diary entry reads:

Battalion attacked enemy front and support lines and succeeded in entering same. The support line was occupied for about ½ hour and the front line for 4 hours. The withdrawal was necessitated by the supply of bombs and ammunition giving out and the heavy enemy barrage on our front line and communication trenches, preventing reinforcements being sent forward. Casualties. OR Killed 21, Missing reported killed 35, Wounded 236, Missing 120. Officers Killed 5, Wounded 7, Missing 5 (see appendix to 12th Battalion war diary dated 30 June 1916 for officers’ names: p.15 of 92) [11].

Above: Map of the opposing trench systems in 1915 (Image – storringtonlhg.org.uk)

The war diary of the 13th battalion went into most detail regarding the attack:

The battalion assembled at 1.30 am on the morning of the 30th June in readiness for the assault, with all four platoons of each coy in the front line.

The preliminary bombardment on the morning of the attack opened at 2.50 am., and at 3.05 the leading wave of the battalion scaled the parapet, the remainder following at 50 yards interval. At the same time the flank attack under Lts. Whitley and Ellis gained a footing in the enemy trench. The passage across NO MAN’S LAND was accomplished with few casualties except in the left companies, which came under very heavy machine gun fire.

The two right companies succeeded in reaching their objective, but the two left companies only succeeded in penetrating the enemy’s wire in one or two places.

Just at this moment a smoke cloud, which was originally designed to mask our advance, drifted right across the front and made it impossible to see more than a few yards ahead. This resulted in all direction being lost and the attack devolving into small bodies of men not knowing which way to go.

Some groups succeeded in entering the support line, engaging the enemy with bombs and bayonet, and organizing the initial stages of a defence.

Other parties swung off to the right and entered the trench where the flank party was operating, causing a great deal of congestion.

On the left, the smoke and darkness made the job of penetrating the enemy wire so difficult that few, if any, succeeded in reaching the enemy trench. Some parties of the right company succeeded in reaching the enemy support line, where they were subjected to an intense bombardment with HE and whizz-bangs.

Capt. Hughes, who was wounded, seeing that his company was in danger of being cut off, gave the order for the evacuation of the enemy trenches, and the remainder of the attacking force returned to our trenches.

The enemy, who was evidently thoroughly prepared, now concentrated his energies on the front line, and, for the space of about 2½ hours, our front and support lines were subjected to an intense bombardment with heavy and light shells, causing a large number of casualties. Ultimately the shelling ceased and to all intents and purposes the operations closed, the battalion being relieved by the 14th Hants at about 1:30pm and taking over their original billets at Vielle Chapelle.

Principal causes of failure.

- The unfortunate incident of the smoke cloud.

- The preparedness of the enemy.

- The intensity of the enemy’s shell and machine gun fire.

- The failure of the artillery to cut the enemy’s wire on the left.

Casualties. Our casualties were unfortunately heavy and resulted in the loss of many valuable officers and men including Capt. C.M. Humble-Crofts, Capt. and Adj. R.D’A. Whittaker, Lt. H.L. Fitzherbert, 2nd Lts. Dudley, Morgan, Oliver, Prior, and Diggens, killed and missing, and Capt. Hughes, Capt. Makalua, Lt. W.W. Fitzherbert, 2nd Lt. Turner. Amongst the wounded were CSM Robinson, CSM James, CSM Sears and CSM Hartley, the latter lost a foot during the bombardment. The enemy casualties are also considered to have been considerable, large numbers of dead being seen in the enemy trenches [12].

Above: deployments of 12th and 13th Battalions RSR (Image – storringtonlhg.org.uk)

Lytton was scathing:

The plan of attack, which had been advertised as skilfully as any patent medicine, was to contain this one element of surprise – namely that a big bombardment was to take place at 5 o’clock one evening, and that the infantry attack would not take place till the following morning at daybreak, after a much shorter bombardment. The first bombardment was a very successful one, and had our chaps rushed over to bayonet the survivors and come back again, it might have been quite a good little show, but during the night they put in new troops and evacuated the wounded, and at zero next morning there was a barrage of artillery and machine gun fire on our trenches so precise that hardly a soul escaped; of the men who went over about ninety per cent became casualties. This accurate German artillery barrage on our front line and assembly trenches proved that our counter battery work was completely ineffective. The plan as regards its local effect was a complete failure – indeed the conception of the attack was so futile that nothing but failure could have resulted. Then as a diversion to the Somme offensive, where some forty divisions were concentrated, it was absurd to do a show where only one brigade was involved. The Divisional General was ungummed, but it seemed to us that there were others who were responsible, and, if they had lost their commands after this failure, possibly greater disasters might have been avoided, for a similar experiment was made a little later on with two divisions and the result was exactly the same. Naturally in the Communiqué our attack appeared as a successful raid – nothing more, and yet our casualties were in excess of the worst day in S. Africa when The Times was printed with black borders [13].

Also serving with the 11th Battalion RSR was the poet and writer Edmund Blunden, holding the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Blunden was not involved in the attack on the Boar’s Head; he was stationed at a dugout in a complex of trenches named Port Arthur two hundred yards behind the front line, adjacent to the La Bassée road towards Neuve Chapelle. He describes the moment the British bombardment began with an initial optimism:

‘Mad ideas of British supremacy flared in me as the quiet sky behind us awoke in a crescent of baying flashes, a half-moon of avenging fires…’ but was soon disabused, ‘those ideas sank instantly, for the eastward sky before us awoke in like fashion, and another equal half-moon of punishing lightnings burst, with the innumerable high voices of machine guns like the spirits of madness in alarm shrilling above the clashing tides of explosion. A minute more, and a torrent of shells was screeching into Port Arthur; we had been in no doubt about receiving this attention, for the place was an “immediate reserve”; we (it was our good fortune) went below’ [14].

Above: Edmund Blunden (Image – wo1.be)

Eventually, a dazed group of soldiers stumbled into Port Arthur having retired from the failed assault. Blunden gave them what refreshments he had to hand, and received a report of the action: ‘In No Man’s Land a deep wide dyke had been met with, not previously observed or considered as an obstacle, which had given the German machine guns hideously simple targets; of those who crossed, most died against the uncut wire, including our colonel’s brother’ (2nd Lt. Francis Grisewood, brother of Col. Harman Grisewood) [15].

Blunden concludes: ‘So the attack on Boar’s Head closed, and so closed the admirable youth or maturity of many a Sussex worthy’ [16].

The three Southdowns battalions suffered heavy casualties, one set of figures reports losses of:

Officers: Killed 8 Wounded 22 Missing 18 Total 48

Other Ranks: Killed 126 Wounded 701 Missing 326 Total 1153 [17]

The 30 June 1916 would henceforth be known as ‘The Day Sussex Died’.

Above: Battle of the Boar’s Head Memorial, Worthing, West Sussex (Image – southcoastview.co.uk)

One of the many casualties was Arthur Gurr. Arthur was wounded in the back by shrapnel during the battle and entered the medical chain of evacuation, arriving in England on 4 July. He died the same day at the Ontario Military Hospital in Orpington, Kent.

Above: Off the beaten track (Photo – Paul Blumsom)

Above: St. Margaret’s Church, Isfield, East Sussex (Photo – Paul Blumsom)

Arthur’s body was returned to his native Sussex. The local newspaper reported on his burial at St. Margaret’s Church, Isfield, in an article titled ‘Fell in the Great Attack’, subtitled ‘Military Funeral at Isfield’ thus:

One of the penalties of the recent successes in France was painfully brought home to residents at Isfield, when on Saturday last one of the men who left his native village to fight the foe, and fell in the cause of his country, was brought home for burial. This was Private Arthur Gurr, son of Mr. and Mrs. Gurr, of Buckham Hill, of the Royal Sussex Regiment, who was wounded on July 1st, and was brought to England on the 4th, but died the same day in a hospital at Orpington, Kent, as the result of wounds in the back caused by shrapnel. He was one of the many men from Isfield who answered the call. He joined up on September 1st, 1914. He was only 20.

The interment was made the occasion of military honours and was attended by a large number of civilians. The scene in the little churchyard was one which will live in the memory of many who were present. The sound of the guns on the distant Front was distinctly audible and overhead a reconnoitring aeroplane hummed steadily. In the meadow adjoining the churchyard a party of haymakers suspended work while the beautiful words of the burial service were being recited by the Vicar (the Rev. H. J. Dyer), and at the time the bleating of lambs was heard in an adjacent field. It was Peace after War. The polished elm coffin was enveloped in the Union Jack. It was preceded by a firing party of 16 men and a trumpeter of the 20th Hussars, six men of which regiment also formed the bearing party, the whole being in charge of a sergeant and a corporal. Whilst the remains were borne into the Church the firing party formed a guard of honour through which they passed and remained resting on their upturned rifles till the last part of the journey to the graveside was commenced. At the conclusion of the impressive service three volleys were fired, the trumpeter sounded the Last Post and the young patriot was left to rest in the grave of an honoured soldier.

The mourners were Mr. and Mrs. Gurr (parents), Miss A. Stevens (fiancée), Mr. Harold Gurr (brother), Mr. and Mrs. A. Rudge (uncle and aunt), Mr. and Mrs. F. Lane (foster brother and sister-in-law), Mr. and Mrs. Davis (Newick), Mrs. Farrell and Mrs. Martin. Major E. H. Thurlow and Mrs. Thurlow were among the many local residents who were present and sent a very handsome wreath composed of coloured roses tied with satin ribbon in the national colours.

The floral tributes were inscribed as follow:

"In loving memory our darling boy, from mother, dad and Harold"

"In loving memory of dear Arthur, from Annie, with deepest love"

“In loving memory of dear Arthur, from Aunt Pat, Dolly and Arthur;"

"With deepest sympathy and ever loving memory of our dearest friend Arthur, from Edward and Rhoda"

“With all honour, sincere respect and regret to Arthur Gurr, who died for his country, from Major and Mrs. E. H. Thurlow”

“In loving memory of Arthur, from Mr and Mrs. Stevens and family"

"With deepest sympathy from Mr. and Mrs. Winter and family"

"With very deep regret from A. Brakefield"

“With deepest sympathy from Mr. and Mrs. Turner and family"

"In loving remembrance of dear Arthur and with deepest sympathy from Fred and Louie"

"From Private G. E. T. Martin, 5th Royal Sussex. B.E.F."

"With deepest sympathy, from Miss Cheale"

“In remembrance of dear Arthur, with deepest sympathy, from Mr. and Mrs. F. Beale (Uckfield)"

"With deepest sympathy, from Mr. and Mrs. Taylor" [18]

Above: Private Arthur Gurr’s CWGC headstone, St. Margaret’s Churchyard (Photo – Paul Blumsom)

Above: Peter the lamb with a contingent of the 11th Battalion (oldfrontline.co.uk)

The mournful bleating of sheep heard during the vicar’s address was surely added to by Peter, the regimental mascot, vocalising his sorrow at the passing of one of Lowther’s lambs. And as this worthy son of Sussex was laid to rest, one could imagine the voices of his phantom comrades carried by the wind across the South Downs, from over the sea:

Sometimes your feet are weary,

Sometimes the way is long,

Sometimes the day is dreary,

Sometimes the world goes wrong;

But if you let your voices ring,

Your care will fly away,

So we'll sing a song as we march along,

Of Sussex by the Sea [19].

Article contributed by Paul Blumsom

References

- Rudyard Kipling, extract from the poem Sussex, in The Definitive Edition of Rudyard Kipling’s Verse, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1989, p.214.

- Neville Lytton, The Press and The General Staff, W. Collins Sons & Co Ltd, Pall Mall, London, 1920, p.3.

- Lytton, p.12.

- Lytton, p.19.

- Lytton, pp.20-1.

- Lytton, p.23.

- Lytton, p.27.

- Extract from C.E.W. Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 – Vol.3, quoted in John A. Baines, The Day Sussex Died: A History of Lowther’s Lambs to the Boar’s Head Massacre, FireStep Books, 2012, p.135.

- Lytton, p.40.

- WO/95/2582-1 War Diary 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, The National Archives.

- WO/95/2582-2 War Diary 12th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, The National Archives.

- WO/95/2582-3 War Diary 13th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment, The National Archives.

- Lytton, p.42.

- Edmund Blunden, Undertones of War, The Folio Society, London, 1989, p.41.

- Blunden, pp.41-2.

- Blunden, p.42.

- Baines, p.194.

- Sussex Agricultural Express, dated Friday 14 July 1916, p.3.

- Verse extracted from Sussex by the Sea by William Ward-Higgs (1907).

Bibliography

Baines, John A, The Day Sussex Died: A History of Lowther’s Lambs to the Boar’s Head Massacre, FireStep Books, 2012.

Blunden, Edmund, Undertones of War, The Folio Society, London, 1989.

Lytton, Neville, The Press and The General Staff, W. Collins Sons & Co Ltd, Pall Mall, London, 1920.

McPhail, Helen and Guest, Philip, On the Trail of the Poets of the Great War: Edmund Blunden, Leo Cooper, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, 1999.