Riding through the ruins of war on the Circuit des Champs de Bataille

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Riding through the ruins of war on the Circuit des Champs de Bataille

In April 1919, barely six months after hostilities had ceased, the toughest bicycle race in history was staged across the former battlefields of the Western Front. It was an event that proved so hard it would never be staged again.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of The Western Front Association we have been dipping into the archives; what follows is an edited version of some of the insights shared with our members back in 2019 by Tom Isitt who had recently written a book on the subject.

Above: Riders racing through the ruins on the Western Front.

'Even as the guns fell silent all along the Western Front in November 1918, a plan was being hatched to celebrate the Allied victory and commemorate the fallen with an extraordinary sporting event. The Circuit des Champs de Bataille - a two-week bicycle race across the battlefields of the Western Front - was the brainchild of Marcel Allain, Editor of Le Petit Journal, one of France’s largest newspapers.

In the early decades of the 20th Century it was common practice for newspapers to organise sports events to increase their circulation figures (this is how the Tour de France came into being), so for Le Petit Journal this seemed like a good opportunity to boost their fortunes and celebrate the end of four years of death and destruction.

The problem for the organisers was that the battlefields had been off-limits to civilians for the last four years and so no one at Le Petit Journal had any real idea what conditions were like.'

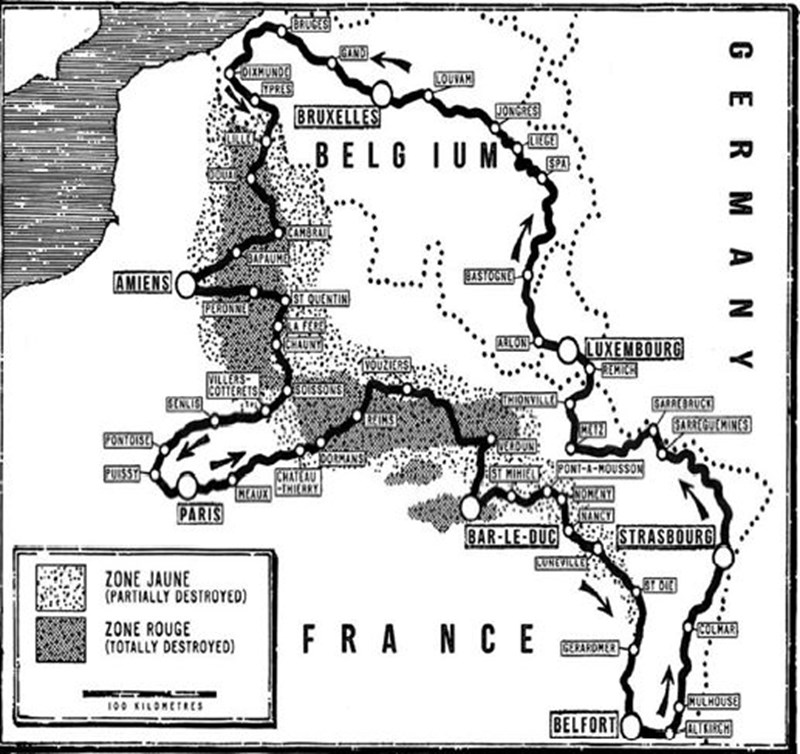

Tour de France organiser Alphonse Steines was sent to reconnoitre a route and subsequently reported back to say that he had mapped one a course that he believed was hard but possible: it would start in the newly reclaimed city of Strasbourg and head north through Luxembourg to Brussels, before turning west and joining the Western Front near Diksmuide. From the coast it would head to Paris via such evocative names as Ypres, Menin, Lille, Cambrai, the Hindenburg Line, Somme, Amiens and St Quentin – and from the French capital, the riders would traverse the former Marne, Champagne, Argonne and Verdun battlefields to St Mihieland the Vosges mountains, before finally turning north again back to Strasbourg.

Above: Map of the race route showing the, totally and partially, destroyed areas.

Above: Racing bikes in those days were primitive and heavy, with only two gears.

The route was 2000km long and would be raced in seven stages of approximately 300km each, with a rest day between each stage. Riders were not allowed help and had to carry their own spares and tools. Stages would finish around 4pm so that results could be published in the following day’s newspaper, which meant they often started at 3am.

The use of performance-enhancing drugs was deemed perfectly acceptable in order to dull the pain the competitors would endure.

On 27 April 1919, 87 riders set off from Strasbourg on the opening stage- most attracted by generous prize money (around £100,000 in today’s terms for the winner and £20,000 for each stage winner). Many of the competitors had served in the war and the majority were French and Belgian.

'There were no British riders (stage racing was banned in the UK at the time), and Germans, Austrians and Hungarians were, for obvious reasons, not allowed,' explained Tom.

Above: Ypres as it was when the race went through in 1919.

The first two stages held little evidence of the war, but that was to change at Stage 3 when the race crossed the battlefields of Flanders and the Somme and the areas designated ‘Zone Rouge’ by the French government -meaning land so war-damaged it was not fit for habitation or cultivation. In 1919 this zone covered 1,200 square kilometres of northern France.

'It was across this brutalised land that the riders raced. Gale-force winds, freezing temperatures, and driving sleet greeted the riders as they turned south from Diksmuide and headed for the Salient,” wrote Tom. “Ypres was nothing but a pile of rubble and the riders struggled past Hellfire Corner and up the remains of the Menin Road at a snail’s pace. From Menin to Bapaume, via Cambrai, the roads were entirely made of smashed and broken cobbles... for 120km.

'It was dark by the time the leading riders reached the Somme, and with no lights on their bikes (and no moonlight) they were riding blind, churning through the wind, sleet and thick mud between Bapaume and Albert. The winner of that Stage finished in Amiens at 11pm, 18 hours and 28 minutes after he set off from Brussels.'

Some of the riders had abandoned the stage and spent the night sheltering in dugouts and trenches before resuming the next day. The last man home in this stage had spent a gruelling 39 hours cycling completing the challenge in appalling conditions.

Stage 4 headed east from Amiens across the battlefields of the 1918 Spring Offensive, through the shattered remains of Villers-Bretoneux and on to St Quentin.

'The countryside here was a treeless wilderness of craters, trenches and rusting belts of barbed wire, colonised by weeds and brambles, and littered with abandoned weapons and rotting clothing. Here and there were solitary crosses marking battlefield burials, and everywhere was the smell of rust and decay. In the ‘fields’ either side of the road burial details were exhuming corpses for reburial in the concentration cemeteries, and labour battalions were being put to work clearing ordnance.'

If this was not bad enough, the racers had not been allowed near the Chemin des Dames as the entire area remained in ruins - and would not be restored until the mid-1920s.

Above: Even the better roads were still very difficult to ride on.

As the riders approached Paris the roads and weather continued to improve, but by now only 24 of the original 87 riders were left.

The route now crossed battlefields of great significance to the French riders: around 75 per cent of all French soldiers had served at Verdun at some point in the war, including most of the French cyclists competing. Thankfully the weather had improved, although the roads remained appalling.

'As they retreated in 1918 the Germans destroyed every building, felled every tree, poisoned all the water supplies, and killed any farm animals they hadn’t sent back to Germany. The devastation was total - progress was agonisingly slow,' explained Tom.

The next major challenge was the Vosges - the Ballond’ Alsace was a significant climb on a heavy bike with only two gears and, to their horror, the riders discovered that there was still a lot of snow on the Ballon. They were obliged to wade waist-deep through snow with their bikes slung over their shoulders.

The final stage was 163km along good roads which had been far behind the front lines. The leader (and overall winner), Charles Deruyter, made it to Strasbourg in five hours to claim his sizable reward. While the winner celebrated, the newspaper was left to rue the event.

Above: Jean Alavoine was one of the famous riders.

Above: Paul Duboc had been another expected front-rider.

The Circuit des Champs de Bataille had not been a success - only 21 out of 87 starters had finished and there had been cheating, bad publicity, and the boost in newspaper sales had been negligible.

'It had been so traumatic for the riders and the organisers that it was never staged again, and it all but disappeared from the record. There is only one cycling history book that even mentions it, and that’s a shame, because it could have been a fitting tribute to the millions who fell in WW1. Instead, it was an abject lesson in bad luck and bad planning,' concluded Tom.

lIf you want to read the full story of the race, Tom Isitt’s book is entitled ‘Riding in the Zone Rouge’ and published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Above: Riding in the Zone Rouge by Tom Isitt.

Original research Tony Isitt. Edited Dr Martin Purdy