Shackleton’s Pall Bearer

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Shackleton’s Pall Bearer

William Sandison, oldest of eight children, was born on the 4th of January, 1898. His post-war experience was typical of many men from the Shetland Islands who returned home from the Great War. William's family grew up in the docks area of the island capital of Lerwick, working in and surrounded by the herring fishing industry. Many Shetlanders relied on sea for their main income, but this reliance grew further with the expansion of the herring trade. The Shetland summer herring fishery, generally successful since the mid-1890s and often with the highest landings of the Scottish fishing districts, was important nationally and internationally. Besides fishermen, the herring season provided work for curers, coopers, gutters, seamen, labourers and clerical workers. [1]

Above: William Andrew Sandison, Shetland Companies Gordon Highlanders, upon enlistment

With the outbreak of war, many Shetland men, like those elsewhere, left the islands to serve their country, these numbers gathering pace particularly into 1915 and 1916. It is estimated over 1,600 Shetland connected men served in land forces during 1914-18, across the many Regiments of Great Britain and the Empire. Although recruitment in Shetland was heavily influenced by links to the sea - in particular the Royal Naval Reserve - for a remote island community the numbers involved in the army were remarkable. Reasons for joining up locally in the Shetland Islands varied - an extra source of income, peer group or female pressure, unemployment, propaganda, fear of invasion, and patriotism.[2]The Gordon Highlanders enlisted almost 400 from the islands. They were also linked to the official Territorial Companies from Shetland as a result of good travel links and communication in Aberdeenshire. During 1914-15, one of the local Territorials first duties was to guard telecommunication cable landfalls throughout the islands. Upon the outbreak of war, William aged just 17, enlisted with them and departed his native island with over 200 fellow Territorials, on the troopship SS Cambria which left a crowded, emotional, Lerwick Harbour on13 June, 1915.[3] While many of these lads worked in jobs connected to the fishing industry, others were in occupations such as bakers, office workers, shop assistants, joiners, or also fresh out of school. Like other Territorial groupings, a common social and occupational identity aided a sense of belonging and cohesion. [4].

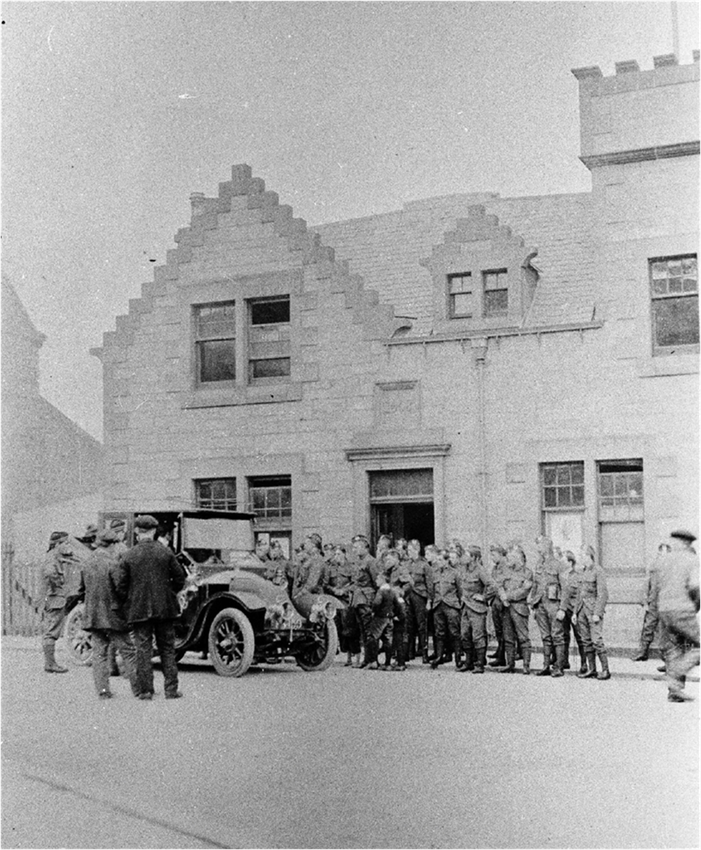

Above: Soldiers of Shetland Companies, Gordon Highlanders, mobilising at Headquarters, Lerwick during the first few days of the war.

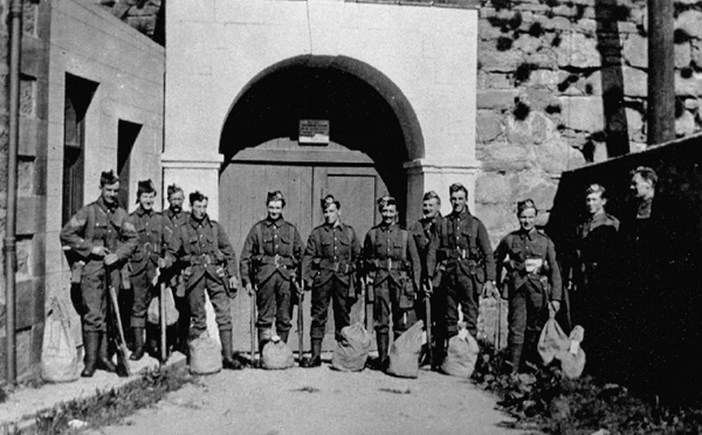

Above: the Shetland Company outside Fort Charlotte on the day they left the Shetland Islands – June 1915

Of those Territorials who left the islands in June, 1915, William was one of 108 who had enlisted for Imperial Service. The Shetland Company Imperial Service men, spent the autumn based at Scone Camp Perth, and were in France by early December of that year with the first detachment on the Western Front. The first draft left Southampton on 3 December, and arrived in Etaples for training on 12 December. Some of these men were with their unit in the field by 21 January 1916. [5] They were integrated into the various Battalions of the Gordons Highlanders on the Western Front, primarily the 4th and 7th and - for some - their initial taste of battle took place at High Wood in July 1916. William was engaged during their first major integrated action of these men at the Battle of the Ancre on the 13th of November 1916. In all, 19 local Gordon Highlanders were killed or died of injuries, primarily with the 51st and 3rd Divisions.[6] William was further engaged in the Battle of Cambrai with his Battalion where his friend, Laurence Cooper, was killed at his side by a sniper in the assault on the village of Flesquieres, 20 November, 1917. [7] Both men were advancing towards the village with a Lewis Gun, very close to Tank Deborah which was raised following the work of Philippe Gorczynksi, and is now in museum in the village as a permanent memorial. Casualties amongst Shetlanders in the Army increased each year, from 6 in 1914, an estimated 67 in 1915, to over 140 in 1916.

Above: Troops of the 51st Division crossing a trench. Ribecourt, 20 November 1917. IWM (Q 6278)

Amongst many other Shetlanders, on 21 March 1918, William was in the line during the St Michael Offensive, with the 51st Highland Division, who were based near the Bapaume-Cambrai Road, forming part of IV Corps. After an intense bombardment, the German attack forced its way up the Louverval valley in the centre of the Division. The 24th German Reserve Division attacked the 51th (Highland) Division again near the west of the Morchies line, with heavy fighting. The 11th Essex facing Morchies line were driven back along with the7th Gordon Highlanders.6th Black Watch, and a company of 9th Loyal North Lancashire Regiment of 25th Division, who formed a shield at the Beaumetz-Morchies switch trench to help the Essex stem further advances. [8]

In more detail, The 7th Gordon Highlanders had been in brigade reserve at Beugny, a demolished village over six miles from the German front line. At 7:54 the Battalion was ordered to send two and a half Companies to the rear trench of the battle zone. This position was taken up with hardly any loss, despite heavy shelling, and was subsequently reinforced until the whole Battalion was upon it, or just in rear of it. The trench was a good one and the wire was intact. The German scouts showed themselves around 300 yards in front, but no serious attempt was made to force this line of defence in the Gordons sector and no progress was made against the 51st Division.During the night the front was reorganized and strengthened by the 57th Brigade (19th Division). The 153rd Brigade, now consisting of the 7th Gordons and small remnants of the two Black Watch battalions, continued to hold the rear trench of the battle zone - known as the Beaumetz Morchies line.A flank was established between the Bapaume-Cambrai road and Beaumetz and held until after dark.During the night of March 22nd, the remnant of the 153rd Brigade, together with the 6th Gordons of the 152nd, was withdrawn to Fremicourt, two and a quarter miles east of Bapaume. The 7th Gordons at this time numbered 8 officers and 100 other ranks.[9] As a result of the action during this period, William obtained a Military Medal, retrospectively alongside a Private W. Waddell on the 13th of September, 1918. This was one of 173 Military Medals awarded to the men of the 7th Battalion between 1914-1918.[10]

The local press recorded that:

‘Pte William Sandison, Gordons, Son of Mr Bruce Sandision, 16 Freefield, Lerwick, had been awarded the Military Medal for gallantry on active service in the field. The award refers to Pte Sandison’s heroism during the opening days of the Great German Offensive on the 21st and 22nd of March, 1918. Pte Sandison, who was formerly a cooper on Messrs Slater’s barrel factory and was in the local Territorial’s when the war broke out, and left Shetland along with the other service men. He had been nearly three years in France and although he had taken part in much hard campaigning and had been through a number of big offensives, had has only once been wounded. Pte Sandison is to be congratulated upon having his gallantry recognised and we wish him best of luck for the future.' [11]

Above: William Sandison

Shortly after Private Sandison was wounded in the leg:-

'Mr Bruce Sandison, Lower Freefield, Lerwick has received word from his son Pte. William Sandison, the Gordons, that he has been wounded in the recent fighting and is now in hospital. Pte Sandison has been about two and a half years in France and although engaged in many important engagements has escaped without any injuries until now'[12]

Following this wound in the leg, William was transferred to the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders on the Italian Front and undertook duties guarding Austro-Hungarian prisoners following operations on the Asiago Plateau and the Battle of Piave. The 2nd Battalion, were part of a force sent to fight alongside the Italian army against the Austrians, holding a sector of the front first at Martello in north east Italy and, from April 1918, on the Asiago Plateau. Although the line was mainly static, the Battalion spent much time in raiding and harassing the enemy. Their most notable battle was on the River Piave at the end of October 1918. Their task was the capture of part of an island, and under heavy fire they successfully captured two objectives. The Austrians then began to withdraw hurriedly all along the front, and the 2nd Gordons pursued them, taking hundreds of prisoners. An armistice came into effect on 4th November. [13]

Above: William Sandison (rear centre), with Austro-Hungarian Prisoners

Following the Armistice, William spent a further 17 months in the Army. A cadre of the 2nd Battalion arrived in Aberdeen from Italy in March 1919. The Battalion then served in Ireland at Collinstown Camp where it was reformed on the 3rd (Special Reserve) Battalion Gordon Highlanders. [14] The Battalion were moved to Lichfield in January 1920. At this juncture an advance party has reached Cologne with a view to service on the Rhine. However, the move was cancelled and that Battalion returned to Scotland instead. In March they arrived at Maryhill Barracks, Glasgow. [15] William's medal card states that he was 'Discharged for Misconduct' on 7 April, 1920. Alongside the Military Medal, he was awarded the 1915 Star. Consequently he forfeited his War Medal and Victory Medal.[16] William Sandison never revealed his misconduct and it remains a family mystery.

William arrived home to a changed local economic and social environment, with scarce employment, and a community affected greatly by war, alongside other the more personal challenges that faced all ex servicemen. The Shetland fishing industry begun to decline before the war, and this continued after the war with fewer people were employed and the amount and value of the catch variable.[17]A subsequent lack of employment forced many Shetlanders, including William, to move to where the work was. For the next few decades he would follow the fishing industry from Shetland to Great Yarmouth as a stevedore in the summer months. Work included loading vessels with salted fish for ports mainly in Germany and Russia.[18] However, during the winter months, work often was spent at the whaling stations in South Georgia.

Above: William Sandison, (fourth from left), in post-war Stevedore duties.

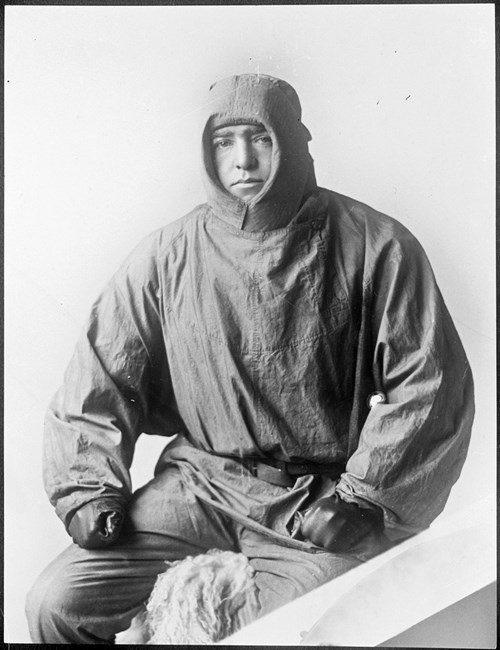

William's earliest time at the whaling, between 1921 and 1922, saw him be right at the heart of a historic moment. He was one of six Shetlanders, all ex servicemen, who were pallbearers at the funeral of British Polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton at South Georgia, who had died on 5 January 1922, aged 47. One of the men, James Brown, was given the responsibility to choose the men for the duty. He picked all Shetlanders.[19] It was originally planned for Shackleton's body to be shipped back to Britain. However, after departure, his widow sent word that, at his own earlier request, that he was to be buried as far south as possible. The ship returned to South Georgia and he was buried at Grytviken on the 5th of March. The Master of the ship conveying Shackleton, S.S. Woodville, was also a Shetlander, Captain Laurence Leask who attended the funeral.[20]

The Explorer had bought a Norwegian ship 'Quest', with a small seaplane and hoped to survey Antarctica from the air. Stalled by logistical and weather challenges, the expedition had headed to South Georgia. [21]

Above: Ernest Shackleton - Photo – www.coolantartica.com

This moment was recorded in The Times by Captain Hussey, a meteorologist to the Shackleton Expedition:-

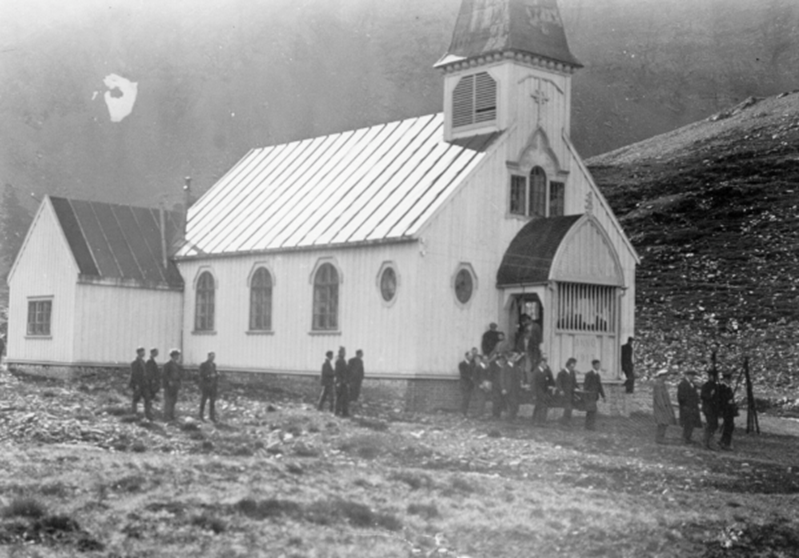

'We arrived in the whaler Woodville with the body of Sir Ernest Shackleton at South Georgia, "the gate of the Antarctic", on February 26th. We took the body ashore on March 1st. The coffin was taken to the Lutheran Church with floral tributes. At 3pm, on March 5th, the manager of the whaling stations on the island and about 100 men assembled at the church. Mr Binnie, the magistrate, and the Customs and other officials representing the Falkland Island Government, were also present.

Just before the service began, Mrs Aaderg, the only women on the island placed a bunch of freshly gathered flowers on the coffin. The Norwegians then sang the first verse of their funeral hymn. Mr Binnie read part of the Burial Service as there is no clergymen on the island. All present repeated the Lord's Prayer. After the second verse of the Norwegian funeral hymn the coffin was lifted by six Shetlanders, from Leith Harbour Whaling Station and was carried over piles of whalebones and many small mountain streams to the little cemetery on the hill where sailors have been buried since 1846. As the cortege left the church, the bell began to toll, and continued till the coffin was lowered into the grave.

In front walked two officials with black funeral banners and behind with myself representing Mr. J.Q. Rowett (who was chiefly responsible for financing the Quest expedition), Lady Shackleton and children, and the Expedition were Mr Binnie and the station managers carrying wreaths. At the gate of the cemetery the British and Norwegian flags were flying at half mast, and about 100 men, mostly Norwegians, were gathered.

As also stated: 'Then the coffin was borne on the shoulders of six stalwart Shetland Islanders, all ex-servicemen, up the hillside to the grave, followed by the cortege of islanders. The funeral is described as: 'the managers even from the most distant stations came to attend it, and one of them, with a fine and understanding sympathy, brought with him from a great distance seven ex-service men from a British Ship, Shetlanders all, to act as bearers on the last stage.' [22]

Above: The funeral service leaving Grytviken Church. (c) Thomas Binnie

Above: Shetland Pall bearers at the funeral of Ernest Shackleton. William Sandison, George Manson, Magnus Leask, John Byrne, James Brown, James Leask. (Shetland Museum and Archives Photo Ref SM00259)

We reached the grave and the coffin was lowered by the Shetlanders with the head towards the South Shackleton loved so well. The Norwegians then sang the third verse of their funeral hymn, and the remainder of the burial service was read by Mr Binnie. Then after the last verse of the funeral hymn, all said the Lord's Prayer'.[23]

All the other servicemen who were in Grytviken that day had their own post-war life. John Bryne, enlisted as a Seaman with the Royal Naval Reserve in 1916, having previously served with the Gordon Highlanders. He served on a hired drifter, Ambitious, following being discharged in December 1919. Following the war he was employed as a baker and the town lamplighter. He lost two brothers during the war. James, 8th , was killed in action at Loos, 25 September, 1915. Andrew, 7th Seaforth Highlanders, was killed on The Somme, 18 June, 1916. John died on the 16 August, 1959. [24] aged 72.

Corporal James Brown, known locally as 'Sodger Brown' served with the 2nd Royal Scots. He was in action at Mons and subsequently awarded the Mons Star. During the war, he was twice wounded. Following discharge, he was also posted on Ambitious. In the 1930s, he worked as a labourer. His date of death is unknown.[25]Magnus Leisk enlisted as a Seaman with the Royal Naval Reserve (Shetland Section) serving as a Gunner on HMS Moniadhla. Following the war, Magnus was employed as a crofter. In the 1970s, Ernest Shackleton's son visited Shetland and was presented with a copy of the photograph of the burial by Magnus. He died on 24 March, 1987.[26]

When following the herring industry into the 1930s, William married Isabella on the 5 November 1931. She also worked in the herring industry as a fish gutter, following the trade around Britain at that time.Following World War Two, William was still at the whaling. A passport photograph of him was taken at Leith on 17 October, 1945, enroute, once more, to the whaling at South Georgia, aged 47 years; quite a different experience no doubt from doing the same job in his early 20s. His wife and son would not see him throughout the winter months.

Like most, William never spoke much about his experiences, although it was often mentioned within his family that his Military Medal was obtained during the March day in 1918 following 'a defensive action holding a position witha Lewis gun'. That medal lay in a top drawer for most of his life, very rarely taken out, looked at, and never polished. Thankfully, it did not find its way into an e-bay market sale and remains treasured by his family and is on display in a framed case, along with replicas of the medals forfeited, on the living room wall. Throughout his life, William took no part in Remembrance parades or ex soldier events, although would often speak about, and sometimes meet up, with his old comrades in the Lerwick British Legion, including the odd pint with 'Sodger Brown'. But very little was also ever mentioned about his attendance at the funeral of . He died on 17 September, 1969.

Above – William Sandison’s grave

Article by Jon Sandison

Thanks also to Jonathan D'Hooghe.

(This article first appeared in Stand To! No 116)

[1] Riddell L, Shetland and the Great War, (The Shetland Times, 2015), p.37

[2] Riddell L. Shetland and the Great War (The Shetland Times, 2015), p.112

[3] The Shetland News, Saturday 19th June 1915, The Shetland Times, Saturday 19th June 1915.

[4] Mitchinson,W, The Territorial Force at War, 1914-16, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), p.29.

[5] Service Record Shetland Territorial, National Archives, WO363.

[6] Sandison, J, That Grim Red Dawn:Shetland's Sacrifice At The Ancre. Shetland Library, 2018.p.12.

[7] Horsfall J and Cave Nigel, Flesquieres, Cambrai, (Leo Cooper, 2003), p.131

[8] Sandison, B, Memoirs of A Lerwick Boy, (The Shetland Times Ltd, 2008).p.4.

[9] Falls C, History of a Regiment, (Aberdeen University Press, 1958), p179-181.

[10] Bert Innes, Gordon Highlanders Museum.

[11]The Shetland News, 19th September, 1918

[12]The Shetland Times, 13th April, 1918.

[13] Wilkes J & Wilks E, The British Army in Italy, 1917-1918, (Pen and Sword. 1998), p.141.

[14] Bert Innes, Gordon Highlanders Museum.

[15] Miles, W. Life of a Regiment, 1919-1945, (Aberdeen University Press, 1961), p.10-11.

[16] William Sandison Medal Card.

[17] Riddell, L, Shetland and the Great War,(The Shetland Times, 2015), p.174.

[18] Sandison, B, Memoirs of A Lerwick Boy, (The Shetland Times Ltd, 2008).p.92

[19] Sandison, B, Memoirs of A Lerwick Boy, (The Shetland Times Ltd, 2008).p.4

[20] Funeral of Sir John Shackleton, Shetland Museum and Archives

[21] The Spirit of Mawson

[22] Mill H.R, The Life of Sir Ernest Shackleton, (Heinemann Ltd, 1922), p.279.

[23] Shackleton's Burial, Captain Hussey, The Times, 4th May, 1922.

[24] Kate Canter, Shetland Family History Records, (John Byrne Zet 47187).

[25] The Shetland Times, 9th March, 1918

[26] Kate Canter, Shetland Family History Records, (Magnus Leisk, Zet 34046).