The Censuring of Lieutenant Colonel John MacCarthy-O’Leary

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Censuring of Lieutenant Colonel John MacCarthy-O’Leary

In February 1918, 55th (West Lancashire) Division took over trenches in the Givenchy sector. The division’s units had sustained severe losses during the German counter-attack at Cambrai at the end of November and had since been rebuilding and training in the rear. During that counter-stroke, 1/5th South Lancashire, of 166 Brigade, had been almost wiped out. Its adjutant later wrote that of the approximately 21 officers and 540 other ranks (ORs) in the line, “Not an officer or a man....came back.” He believed that, “The fighting qualities of the Regiment were displayed at their best and a wonderful example had been given to the new battalion.” During January and February drafts arrived which, by 2 March, had rebuilt the battalion to a strength of42 officers and 982 ORs. The unit also received a new commanding officer (CO), Lieutenant Colonel John MacCarthy-O’Leary.[1] Within weeks of joining his battalion, MacCarthy-O’Leary was to be placed under severe scrutiny by a court of inquiry, the outcome of which almost cost him his command. Furthermore, and probably as a consequence of the incident under investigation, one of his junior officers shot himself.[2]

John MacCarthy-O’Leary was the son of a CO of 1/South Lancashire Regiment who had been killed during the Boer War. John had attended Stonyhurst and was commissioned into his father’s regiment in March 1901.

Above: Stonyhurst College, Clitheroe (c) Visit Lancashire 2021

At the outbreak of war in August 1914 he was a major in 1/South Lancashire, which was then stationed in Quetta. The battalion remained in India throughout the war but in 1916, MacCarthy-O’Leary was posted to the UK. He went to France in November of that year and was wounded within seven days of his arrival.[3]

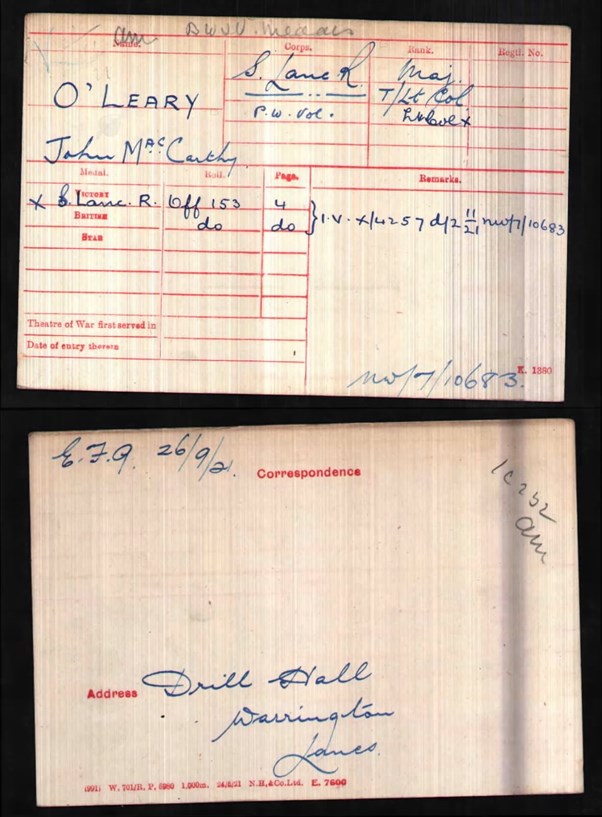

Above: MacCarthy-O’Leary's Medal Index Card

On recovery, he attended the Senior Officers Command Course at Aldershot. At that time the Commandant of the command school was Brigadier General R.J.Kentish.

Above: Brigadier General R.J.Kentish

Above: Senior Officers' School at Earlstoke Park House, Wiltshire (destroyed by fire in 1950). J.P. Neale’s Views of Seats of Noblemen and Gentlemen

In early December 1917, following 55th Division’s mauling at Cambrai, Kentish was appointed GOC of its 166 Brigade.[4] Seemingly to have recalled the sound leadership qualities displayed by MacCarthy-O’Leary whilst he attended the course at Aldershot, Kentish requested the authorities to appoint MacCarthy-O’Leary as CO to the rebuilding 1/5th South Lancashire. MacCarthy-O’Leary returned to France on 23 December and joined the unit on 4 January 1918. When he took command, therefore, and although he was an officer of the Regular Army with more than 17 years service, MacCarthy-O’Leary had had only seven day’s experience of warfare on the Western Front.

On 9 March 1918, during the temporary absence of the GOC 55th Division, a court of inquiry was convened by the division’s senior artillery officer, Brigadier General A.M.Perreau. The court was to investigate the events of a raid on 1/5th South Lancashire in the early hours of 7 March 1918 in which 23 of its men were captured. The battalion’s war diary makes only brief mention of the raid, and the divisional history dismisses the event very simply. The brigade war diary offers a little more detail, noting that 23 ORs were missing and total casualties as being about 50 all ranks. The divisional WD also mentions the 23 missing ORs. It also asserts that the divisional artillery had reacted promptly, and that although the enemy were driven off, one post appears to have been “overwhelmed.” Headquarters of I Corps recorded the raid and noted “some of our men were captured.” It was, however, the compiler of First Army’s war diary who collected and retained what seems to be a good proportion of the relevant orders and reports.

Above: An embroidered badge showing the divisional sign

The West Lancashire Division inherited an area which had been much fought over and battered since October 1914. With the expectation widespread across the BEF that the Germans would launch a major offensive, divisional HQ (DHQ) was concerned about the state of the breastworks and keeps, and anxious to gather intelligence about what the enemy might be scheming. On 24 February, patrols were ordered to be sent out daily from an hour before dawn and were not to return until daylight had broken. Furthermore, “Strict vigilance” was to be maintained after the troops have been stood down following the morning stand to. Two days later, DHQ ordered it was imperative that any gaps made in the wire by enemy artillery or mortars were to be fully repaired the following night. This message was immediately passed, with considerable emphasis on its importance, to all brigade (BHQ), and subsequently battalion HQ (BnHQ). DHQ, however, felt that battalion commanders were not taking the entreaty to adhere completely to its wishes sufficiently strongly. On 2 March, the formation’s commander, (GOC) , issued a particularly strong condemnation of his COs’ alleged complacent attitude. He abhorred the apparent failure of his commanders to learn the lessons of the past, and particularly those of 30 November 1917. He wrote, “We talk wiring but don’t do it – and this is in spite of the fact that we might at any time be attacked by overwhelming numbers.” According to Major General Jeudwine, GOC 55th (West Lancashire) Division, the “apathy” of battalion COs “passes comprehension.” He insisted “men should be worked to the bone,” and casualties “must be incurred” until the defences, and in particular the wire, were sufficient to hamper significantly any attacking enemy. Commanders who failed to protect their defences and their men were to be held personally responsible. It was this continuing concern over the lack of wiring which was ultimately to lead to the court of inquiry into MacCarthy-O’Leary’s leadership.

Above: Major General Jeudwine, GOC 55th (West Lancashire) Division

From the beginning of March, increasing enemy artillery and trench mortar activity along the divisional front caused additional suspicion as to likely German intent. On 6 March, Brigadier General Kentish circulated his battalion commanders with a warning that, “It may be that he contemplates a raid; it may be something more serious.” He ordered all intelligence officers and observers to do “everything in their power” to anticipate events. Kentish was clearly unhappy with the layout and positioning of the posts his brigade now held. He objected to what were, effectively, isolated posts being held in strength. Possessing few, if any dugouts, they “lent themselves admirably to enemy enterprise.” If attacked, Kentish predicted large numbers of the garrisons would be killed or captured. He recommended instead that the company holding the forward positions should be deployed in depth, with the forward posts being held lightly as little more than listening posts. Sentries were to be positioned on the flanks and the whole system regularly patrolled. The existing system, however, remained unaltered. It is unknown whether Kentish informed Jeudwine of his criticisms and doubts before the raid on 7 March.

The same day as his circular reached battalions, Kentish paid a visit to BnHQ of 1/5th South Lancashire. Observing the cut wire and a razed parapet in front of Barnton Post No.1, Kentish told MacCarthy-O’Leary to expect a raid. He ordered the CO to ensure officers were continuously present in the two flank posts, Barnton No.1 (South) and No.3 (North).

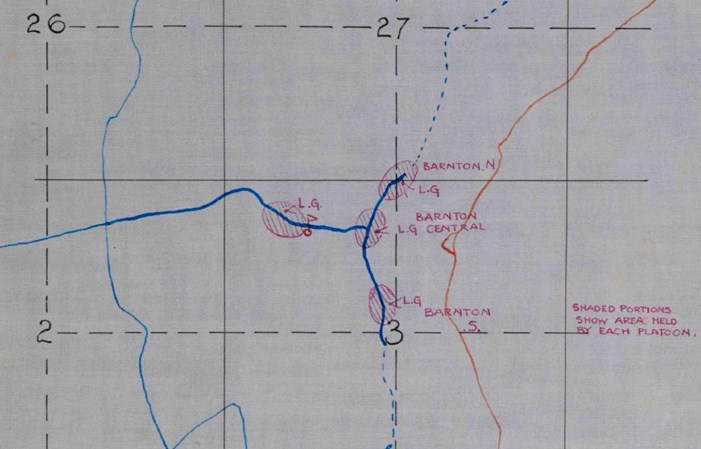

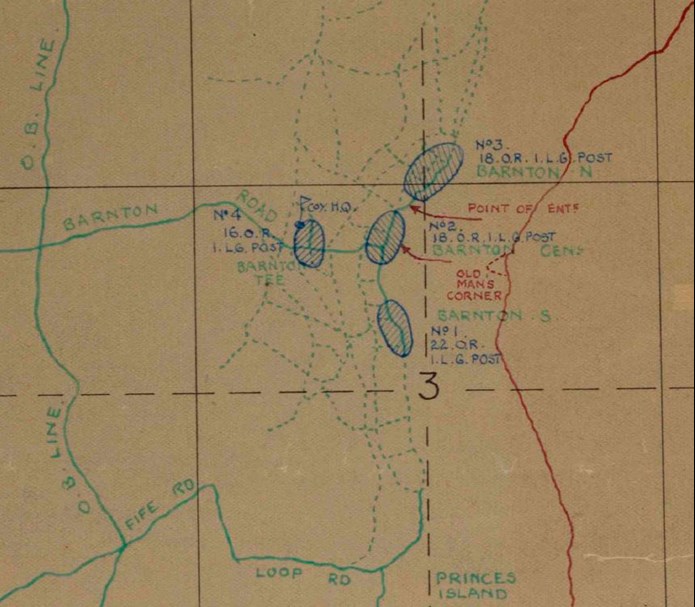

Above: map from the war diary of the General Staff of 55th (West Lancashire) Division (First Army WD, TNA.WO95.175)

Because there were insufficient officers available to have one stationed permanently in No.2 (Central), that post was to be regularly visited by an officer during the hours of darkness.[5] He later claimed he told all the South Lancashire troops he met in the trenches that, “Whatever happens hold on and fight to a finish.” MacCarthy-O’Leary later stated that when he toured the lines at 9pm that evening, he passed on Kentish’s instructions about how the posts were to be manned to Second Lieutenant Henry Pickering of B Company. On the morning of 5 March, the company commander and his deputy had both been wounded and evacuated. As the senior of three subalterns still with the company, Pickering had immediately been appointed officer commanding (OC) B Company. At some time in the afternoon of 6 March, he despatched a message to MacCarthy-O’Leary which stated, “I think there is something more than retaliation in his (ie the enemy’s) activity.” In support of his theory that something was likely to occur he requested BnHQ to send forward two additional Lewis guns. MacCarthy-O’Leary refused the request because he “did not wish to crowd the line.”

Above: Sentry in a trench looking through a box periscope (IWM Q4654)

Following his meeting at BnHQ with MacCarthy-O’Leary, Kentish sent a note to Lieutenant Colonel Cornes, OC 84 Brigade RFA, warning him that there might be a raid that night. In response to the enemy shelling and mortaring, Cornes had ordered several shoots on their suspected positions and batteries during 5 – 6 March. He had authority to act on his own initiative if communications were severed and, following Kentish’s note, he placed his own batteries, the heavy artillery, and the observation post teams on alert. He warned the battery commanders to be prepared to switch quickly from their normal SOS lines to an alternative programme. The divisional machine-gun battalion was also alerted with the result that on the morning of 7 March the crews of C Company began stand to 30 minutes earlier than usual.

That a raid, or perhaps even something stronger, was expected in the very near future was widely understood and measures were thus in place to cope with the eventuality. What remained still to be addressed, however, was the large gap in the wire in front of No.2 Post. The gap had been officially noted several times; another report was submitted by a patrol which examined it on the night of 5-6 March. On 5 March, the staff captain of 166 brigade issued authority for 64 medium and 120 short pickets to be drawn from the RE dump by 1/5th South Lancashire. At noon the following day he again wired BnHQ with authority to draw as many as the wiring party needed of the 500 long pickets which were expected to arrive that afternoon. Armed with an indent issued by Second Lieutenant Holt of C Company for 32 six foot screw pickets, 64 anchorage pickets, and 28 coils of wire, Lance Corporal Bradley took his party to the dump. There, he was told by the sapper in charge that he could not take any six foot pickets because he possessed no signed authority from the staff captain. Bradley drew 100 of the four foot pickets and reported back to Holt. At the court of inquiry Holt stated that his company commander, Captain Nesbett, had told him that he should wire the 50-60 yard wide gap in front of No.2 Post using only six foot pickets. Furthermore, Holt stated that having seen the gap he had himself concluded that trying to use four foot rather than six foot pickets “would be of no use.” While Holt was assessing the gaps in the flank wire, MacCarthy-O’Leary arrived in the trench. On hearing of the subaltern’s problem, the CO told Holt to wire the gap on the left flank and ignore the front area because it would have involved noisily driving in wooden posts. In a later statement MacCarthy-O’Leary declared, “At the time I had forgotten the gap in front of No.2 Post.” Curiously, because he appears to have had no orders to organize any wiring party himself, Second Lieutenant Pickering told the inquiry that he had not attempted any because “no men were available.” There had clearly been problems with the staff work and in the allocation of responsibilities but in the mind of Lieutenant General Holland, GOC I Corps, the principal fault lay with MacCarthy-O’Leary’s “neglect of very emphatic orders” in ensuring that damage to wire was repaired the following night. This was a “neglect” which Major General Jeudwine considered ‘incomprehensible.’

At about 5am, in thick mist and under an intense bombardment, three German officers and 120 ORs attacked the Barnton Posts. They made their way through the gap in the wire in front of Nos.2 and 3 Posts and spread out.

No.3 Post resisted reasonably strongly, but lost seven men of the Lewis gun section as prisoners. There were three wounded men of the garrison of 18. On later examination the Lewis gun had clearly suffered a stoppage and was covered in blood. Under the command of Second Lieutenant Burgess, who had only arrived at the battalion the previous morning, the garrison of No.1 Post drove off the attackers and took two prisoners. It was, however, at No.2, with a garrison of 22 men, where the enemy enjoyed his greatest success. When it was reoccupied after the enemy had disappeared, there were signs of bombs having been thrown but none of any serious fighting. Several of the defenders’ rifles were lined up on or leaning against the parapet; others were scattered around.

Above: Men of the Lancashire Fusiliers sit in a muddy puddle on the floor of a front line trench to clean a Lewis gun. Behind them, as the trench bends round to the right, a group of men can be seen standing in the trench, one of them with his bayonet fixed. To the left of the photographs, can be seen the gas alarm horn and wind vane. Several rows of sandbags form the top left-hand edge of the trench. IWM Q4649 Dynamichrome image.

A Lewis gun which had not been fired was in its position. There was one body in the trench and another on the wire. As per his orders, Burgess had visited the post several times during the night and on the last occasion, between 4am-4.30am, he had witnessed the garrison to be on the alert and manning the fire-step. One of the sentries, Rifleman Barker, told the court that when he saw three of four of his colleagues coming along the trench towards him through the mist with raised hands, he leapt into a shell hole and watched as around 20 Germans followed behind what were obviously British captives. It was assumed that the post had been “overwhelmed.”

The issues that were most pertinent to the inquiry were: whether the British guns reacted effectively and quickly; why the standing orders for patrols had been ignored; why the wire had not been repaired; to make an assessment of the general fighting power and discipline within MacCarthy-O’Leary’s battalion. The reaction of the artillery and machine guns to the raid was quickly settled. Several of the witness questioned said they had little idea of when the British guns opened up but evidence from Lieutenant Colonels Cornes and Topping stated that although they had not seen any SOS signals, they had ordered their guns to fire on the SOS lines as soon as the German bombardment began. All of Cornes’ batteries responded within two minutes of receipt of the order. All communications with the left and right battalions were quickly severed but at 5.20am Brigadier General Kentish rang Cornes and told him to switch his fire from the normal SOS lines to those which had been agreed the day before. At 6.30am, Kentish rang again and told Cornes to cease fire. Topping, OC Right Group, ordered his batteries to reduce to the slow rate at 5.50am and then to cease completely at 5.55am. The machine guns of Second Lieutenant Brooks’ C Company of 55 Bn MGC, fired on their SOS lines immediately the German bombardment began. None of his guns’ SOS lines were, however, targeted on no man’s land.

Above: Two British soldiers man a Vickers machine gun during World War I. (Photo from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Why the battalion had seemingly ignored DHQ orders for patrolling was less easy to resolve. Led by Second Lieutenant Forbes and Sergeant Finnigan, a total of seven men went out into no man’s land at 4.15am. MacCarthy-O’Leary later insisted that he had issued copies of standing orders for all patrols to all companies on 4 March. He also said that he had given particular instructions for Forbes’ early morning patrol on 7 March the evening before. The orders specified that the patrol was not to return before daylight. Instead, Forbes brought his men back in at 4.50am, approximately an hour before he should have done. Forbes was wounded and evacuated during the raid and was thought still to be carrying the original orders in his pocket. When questioned, Sergeant Finnigan claimed ignorance of what actually were the precise instructions for the patrol.[6] MacCarthy-O’Leary was thus able to testify with complete justification that the patrol had failed to obey his orders but, as Jeudwine queried later, why had MacCarthy-O’Leary sent out only one patrol on a night when it was evident that something was brewing? This, the GOC division declared demonstrated a “want of ordinary soldierly precaution.” That was a question which warranted an answer but it is difficult to see what a patrol of seven men, armed only with revolvers and rifles, could have done to disrupt seriously the passage across no man’s land of 123 men even if it had stayed out until daylight. It may be that Forbes did not venture close enough to the German lines and, by returning early, vouchsafed any chance of realising something was afoot. If it had, an early return to give a warning would have been justified.

The evidence heard by the court of inquiry and the subsequent submission of thoughts and opinions by senior commanders were sufficient to condemn MacCarthy-O’Leary. His principal failure was not to adhere strictly to the orders regarding the immediate repair of blown wire. The flaw in brigade staff work, and an admitted error on the part of the battalion’s second-in-command over the issue, did him no favours but he bore direct responsibility for instructing Second Lieutenant Holt to ignore the wide gap in front No.2 Post and to concentrate instead on wiring the flank. As battalion commander he was also responsibility for exerting an acceptable degree of command, leadership and management over the officers and men within his unit. This boils down to ensuring that the morale, and thus the quality of fighting power of the personnel were maintained at a resolute and efficient level. In the opinion of the senior commanders, the battalion’s fighting power left a lot to be desired. Lieutenant General Holland described the “main cause of failure as the want of any fighting spirit in the garrison of No.2 Post.” The lack of bodies proved that the post could not have been overwhelmed simply by the bombardment. The number of unused British rifles and the disappearance, “under the eyes” of the rest of the garrison of seven of No.3 Post’s Lewis gun team, attested to a lack of any prolonged resistance. Holland thought a contributory cause of the failure was the “neglect of the very emphatic orders as to wiring” but that 58 soldiers, with three Lewis guns, could not repulse a raid by 123 of the enemy meant that the “facts speak for themselves and reflect badly on the Battalion.”

In his initial report written two days after the raid and before the court of inquiry convened, Brigadier General Kentish, the man who had requested that MacCarthy-O’Leary be appointed to command one of his brigade’s battalions, was essentially sympathetic to the battalion and its commander. He accepted that MacCarthy-O’Leary had wrongly neglected the orders regarding the repair and maintenance of the wire, but decided to reserve judgement on the fighting spirit of garrisons until the inquiry had heard the evidence. He did, however, offer some extenuating information. He pointed out that the battalion was almost entirely new and that this was the first time most of the men had been in the trenches. The forward company had been trench mortared for two days and nights, was clearly suffering from fatigue, and there were no concrete shelters in the forward trenches. The company commander and his second-in-command had both been wounded and evacuated under 48 hours before the raid. That had left the company short of officers, with a very inexperienced commander, and with another subaltern who had been with it for only one day. As a parting shot, he reported that in an attempt to redeem the battalion’s reputation, MacCarthy-O’Leary had asked that the unit be allowed to conduct a raid as soon as possible.

In his second report, written after the evidence had been gathered and heard, Kentish was rather more critical of MacCarthy-O’Leary. Nonetheless, it is evident that the brigadier retained a good degree of sympathy with both the CO and his battalion. Kentish made it clear that he had himself followed Jeudwine’s instructions to the letter and had emphasised and passed on to his subordinates the importance of the issues specified by the GOC division. As he wrote, “I have preached wire and its importance ever since I have taken over this Brigade.” In a less assertive tone he then pointed out that, “A Commanding Officer has an exceedingly difficult position to-day with the Officers and especially the Company Commanders being what they are.” He did not mention Second Lieutenant Pickering by name but rather mysteriously added that although Pickering had only been appointed by default the day before, as company commander he “ought to have assisted his Commanding Officer.” He continued with, “I am sure he did it to the best of his ability. This Officer has since shot himself, and it is therefore useless to pursue this matter further.” Finally, Kentish explained that he had not wanted to take further action with regard to interviewing men and officers involved in the raid until after the battalion had come out of the trenches. To have done so would have added to the troubles of the CO and perhaps lowered the morale of the men holding what were two difficult sections of trenches. As he wrote, “The battalion is an entirely new one and requires very careful handling.”

Kentish despatched his observations and recommendations to Jeudwine on 20 March. It is likely the divisional commander had already come to a conclusion about how the affair should be handled and that Kentish’s submission merely reinforced that conclusion. Jeudwine had studied the evidence and sent a memo, with other relevant submissions attached, to Lieutenant General Holland at I Corps HQ.

Above: Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Holland

In the memo, the divisional commander assured his corps commander that Brigadier General Kentish had entirely fulfilled Jeudwine’s expectations about how the commander’s intent should be relayed to unit and sub-unit commanders. In a scathing paragraph he next went on to condemn MacCarthy O’Leary for failing to issue adequate instructions or to use “ordinary care to ensure that those issued were understood and carried out.” The tone of his final paragraph was, however, considerably more concessionary. This could perhaps be interpreted as an exercise in self-justification. He had, after all, endorsed the recommendation of his brigadier in having the combat inexperienced MacCarthy-O’Leary appointed to command. In his concluding sentences Jeudwine constructed a strong defence of his subordinate and of his ability as a battalion commander. He wrote that since MacCarthy-O’Leary had been appointed he had proved to be a capable and “valuable commanding officer in spite of the neglect which in this case I cannot acquit him of.” He had concluded that sacking the CO might work as a deterrent to others but that it would be better for the service and for the division if he were retained in command. The issue would have taught MacCarthy O’Leary a lesson “which he will never forget, and will increase his value.” Given his angry memo of 2 March about the alleged inadequacies and “apathy” of his battalion commanders as a whole it is possible that Jeudwine also believed that such a lesson would be beneficially learned by all. He asked the corps commander for his authority to be allowed to settle the matter in the way suggested.

On receipt of Jeudwine’s memo, Lieutenant General Holland wrote to First Army HQ concurring with the divisional commander’s suggestion that the issue should be dealt with at divisional level. General Horne was of the opinion that “great blame” should be laid at the door of the CO, that MacCarthy-O’Leary had failed to display a “proper sense of his responsibilities,” and that the “poor fighting spirit displayed by the garrisons of the posts points to a lack of discipline in the battalion,” That was enough, he argued, for MacCarthy-O’Leary to be relieved of his command. Despite this “strong case for removal,” however, General Horne opted to accept Jeudwine’s suggestion and ordered that MacCarthy-O’Leary should be severely censured but that he would be allowed to retain his command. With that seemingly pragmatic and sensible decision, the awkward issue was resolved.

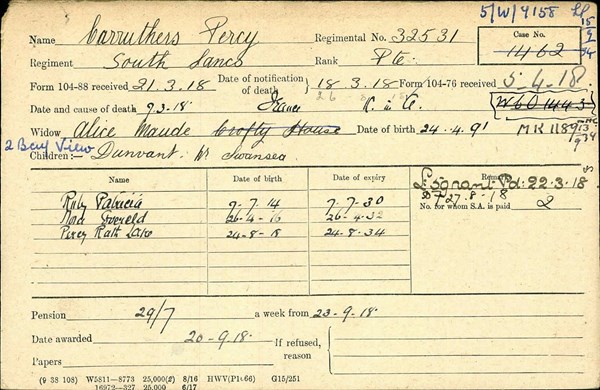

The four members of 1/5th South Lancashire who died during the raid or the bombardment (William Barber, Percy Carruthers, Sam Diggle and John Jones) were buried alongside each other in Gorre British and Indian Cemetery.

Above and below: Two of the fatalities pension records show they came from Heywood and Swansea respectively.

Above: Gorre British and Indian Cemetery (c) CWGC 2021

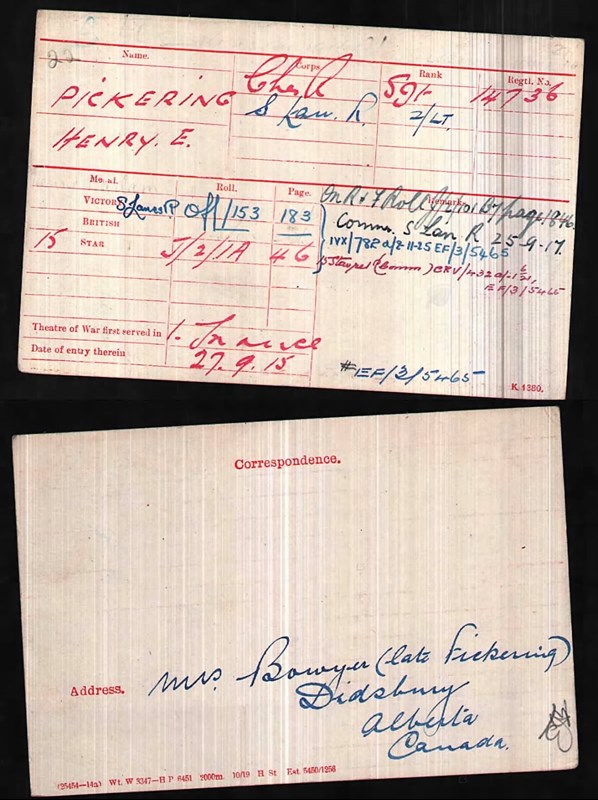

Neither Henry Pickering's age, nor his parents’ names and residence, or those of his wife, appear in the register. There is no inscription on his headstone.

Above: The Medal Index Card for Henry Pickering, showing his wife (?) living in Canada.

Other records show that he was 23 years of age at the time of his death. His father was an engine minder in a corn mill; Henry had been employed before the war as a van driver’s assistant. He enlisted with his brother in September 1915 and fought on the Somme with 10/Cheshire.[7]

In 1917, as a temporary company sergeant major, he was sent to an officer cadet battalion in the UK and later commissioned into the South Lancashire Regiment. He had been married in May 1917 but his widow possibly either did not receive the Imperial War Graves Commission’s form asking what information the next-of-kin wanted on the headstone, or perhaps chose to ignore it. [8]

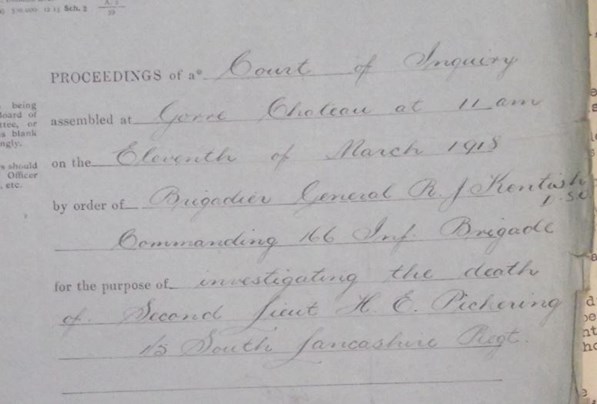

According to witnesses questioned during the court of enquiry into Pickering’s suicide, the young officer was reported to have believed he would be held responsible for what a fellow subaltern described as ‘the calamity’ of the enemy raid. Another witness spoke of Pickering being depressed and unusually curt to his NCOs in the two days following the raid.[9]

Above: The first page of the 'Court of Enquiry' within his file at The National Archives (PRO:TNA WO 339/111304)

It was thus probably the prospect of an inquiry into his actions during the raid which disturbed his mind. Apart from Kentish’s vague statement that “he ought to have assisted his Commanding Officer,” there is nothing in the extant evidence to suggest that Pickering had failed in his duty. For the benefit of the enquiry, Major General Jeudwine stated , ‘I do not consider that he was in any way to blame for the result of the enemy raid.’ Having been thrust prematurely into command of a company, the events of that early morning might have under-mined his self-confidence as an officer and aroused in him feelings of guilt or shame. Given his reasonably humble background there was perhaps already a degree of self-consciousness at being what A.P.Herbert later disparagingly described as a commissioned “boot-faced NCO.”[10] He may simply have decided, as one of the witnesses testified, that he could not face the responsibility and the horrors of warfare any longer. Turning his revolver on himself seemed an acceptable alternative.

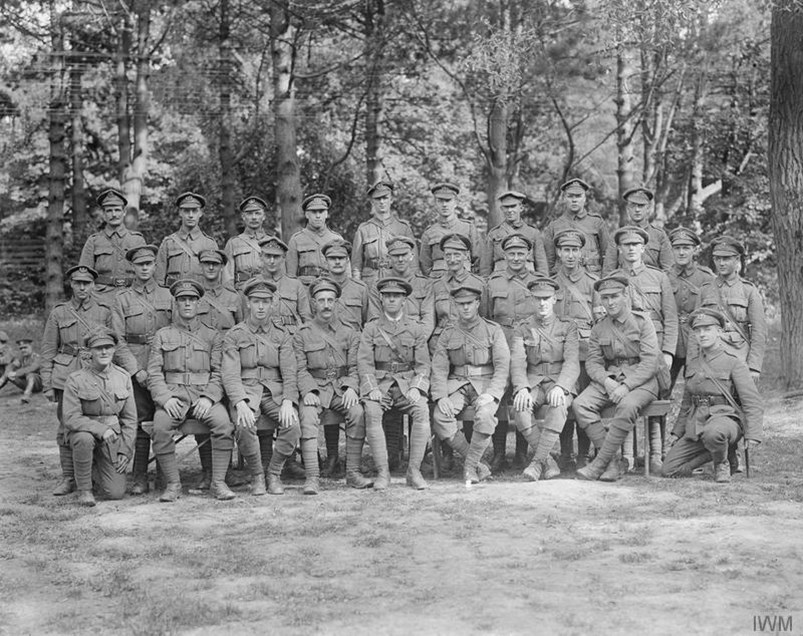

Above: Staff of 1/5th Battalion, South Lancashire Regiment near Bethune, 5 September 1918. IWM Q9430

In contrast, John MacCarthy-O’Leary was an officer of the Regular Army and came from an established landed family of County Cork. As a battalion commander his father had died a suitable solder’s death; one of his brothers had been killed on the Somme in 1916.[11] He had himself been recommended for command by a former commandant of a senior officers’ training school.

Lieutenant Colonel John MacCarthy-O’Leary’s name disappears from the battalion war diary in May 1918; a new CO assumed command on 12 June. There is no indication as to why MacCarthy-O’Leary left. He may have been wounded during the division’s battle at Givenchy in April, or sent home for a rest. On 16 July he arrived at 8/Royal Irish Regiment, a B Battalion in the rebuilt 40th Division, as second-in-command. He became its CO later that month and left the battalion in March 1919. He died in 1923.

It might be interesting to speculate that if the “neglect” of duty and the same abdication of certain responsibilities had been committed by an officer commissioned into the New Armies or the Territorial Force, the outcome of the inquiry into the events of that March morning might have been different.

Above: Lieutenant Colonel John MacCarthy-O’Leary's father's statue in Queens Gardens Warrington commemorating those who served in the Boer War

Above: Memorial to the 55th (West Lancashire) Division at Givenchy. Image (C) 2021 Discovering the Hiking and Cycling Routes of the Remembrance Trail

Article by Bill Mitchinson

[1] In some official records the surname can be spelt and presented in different ways.

[2] The papers covering the matter were chanced on in First Army War Diary, TNA.WO95.175, March 1918.

[3] It is unrecorded as to which battalion MacCarthy-O’Leary joined in France. It does not seem, however, to have been any of those of the South Lancashire Regiment.

[4] Before being appointed to Aldershot, Kentish had for six months commanded 76 Brigade in 3rd Division.

[5] The three Barnton Posts stretched north-south for about 250 yards from approximately 400 yards south of Quinque Rue. They ran roughly parallel to Yellow Road, east of Festubert.

[6] Sgt T Finnigan was to be killed on 11 April 1918

[7] He and his brother, William, had successive regimental numbers. William died of wounds in the UK in July 1916. The family lived in Lostock Gralam, Northwich.

[8] Despite being buried in a cemetery close to the family home, neither does William Pickering’s headstone have an inscription.

[9] Correspondence extending into the post-war period between the War Office and the Pickering family, in addition to the papers covering the court of inquiry into his death, can be found in: https://bit.ly/3xYFgwN I owe this reference, with thanks, to Tony Hearn.

[10] A.P. Herbert, The Secret Battle, (Methuen, 1919, Collector’s Library edition, 2015, p146)

[11] Lt Willliam MacCarthy-O’Leary, 1/Royal Munster Fusiliers, kia 7 September 1916. A statue of Lt.Col. William MacCarthy-O’Leary surmounts the memorial to soldiers of the South Lancashire Regiment who died in the Boer War. It was unveiled in 1907 and stands in Queen’s Gardens, Warrington.