The Coldstream Guards and Irish Guards at Cuinchy 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Coldstream Guards and Irish Guards at Cuinchy 1915

Cuinchy is a village astride the La Bassée Canal and is referred to by Robert Graves in his classic memoir Goodbye to All That:

'Cuinchy bred rats. They came up from the canal, fed on the plentiful corpses, and multiplied exceedingly. While I stayed here with the Welsh, a new officer joined the company... When he turned in that night, he heard a scuffling, shone his torch on the bed, and found two rats on his blanket tussling for the possession of a severed hand.'

The British sector was to the east of Cuinchy: the front line ran 800 yards to the east of the village. The line here formed a salient; from the canal it ran towards the railway triangle, which was in German hands, and then back to the main road.

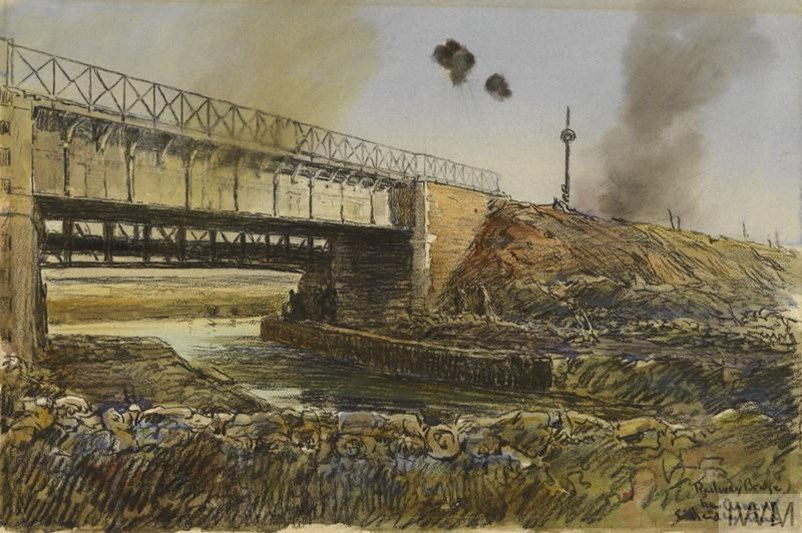

Above: The ruins of the distillery at Cuinchy, early in the war.

The country was utterly flat, with the Bethune-La Bassée railway running on an embankment along the south bank of the canal.

Above: The Railway Bridge near Cuinchy by E. Handley-Read. (Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.) The description of this watercolour reads “A view of a railway bridge over the Canal-d'Aire near the French village of Cuinchy. There are two large clouds of smoke emanating from the railway, as well as two smaller black clouds of anti-aircraft fire in between the larger clouds.”

In late January 1915 the British front line was occupied by the British 2nd Division, one of whose Brigades was the 4th (Guards) brigade, which comprised 2/Grenadier Guards, 2/Coldstream Guards, 3/Coldstream Guards and 1/Irish Guards.

The War Diary for the 1/Coldstream Guards The National Archives (TNA) [WO95/1263] describes the last few days in January:

23rd January CAMBRIN: The Battalion left CAMBRIN and went into the trenches at CUINCHY, relieving the London Scottish – trenches had not been completed. Communication trenches bad and some trenches full of water – heavy rain all night.

24th January CUINCHY: The Germans shelled the position most of the day with their heavy guns – most of the fire being directed on PONT FIXE. Impossible for working parties to be utilized on improving the trenches.

On 25th January the 1/Coldstream Guards were in the trenches when, at 7.30am, a number of mines were exploded and the Germans attacked. The defenders were forced back into a keep among the brickstacks until relieved that night by the 1st Guards Brigade. The war diary describes the day:

25th January CUINCHY: About 7am a German deserter came in and reported an attack imminent. The German attack commenced by the explosion of a mine in the trench held by No. 4 Coy. under Capt. Campbell. The first line of trenches were consequently rushed by the Germans. No. 1 Coy. on the embankment by the La Bassée Canal held its ground and No. 2 Coy. under Lt. Viscount Acheson held on to the keep and Brickstacks and repelled the German attacks. The Scots Guards on our immediate right shared a similar fate but were able to maintain a stand at the Brickfields Reinforcements and London Scottish, Black Watch and Cameron Highlanders were sent up and a counter attack was made but it was found impossible to dislodge the Germans from the front trenches they had taken.

The Infamous Brickstacks

The flat ground near Cuinchy was covered by about thirty brick stacks, which were about 16 feet high, still standing where they were made just prior to the war. They were a formidable obstacle in an attack and equally useful as a shelter in defence. Most were within German lines with others lying inside British territory.

Above: Part of the landscape at Cuinchy. Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum: Q686

The German attack of 25 January is described in some detail by Rudyard Kipling in The Irish Guards in the Great War, Volume 1.

Their work was interrupted by another “Kaiser-battle,” obediently planned to celebrate the All Highest’s birthday. It began on the 25th January with a demonstration along the whole flat front from Festubert to Vermelles. … Owing to the mud, the [Cuinchy] salient was lightly manned by half a battalion of the Scots Guards and half a battalion of the Coldstream. Their trenches were wiped out by the artillery attack and their line fell back, perhaps half a mile, to a partially prepared position among the brick-fields and railway lines between the Aire–La Bassée Canal and the La Bassée–Béthune road. Here fighting continued with reinforcements and counter-attacks knee deep in mud till the enemy were checked and a none too stable defence made good between a mess of German communication trenches and a keep or redoubt held by the British among the huge brick-stacks by the railway. So far as the [Irish Guards] Battalion was concerned, this phase of the affair seems to have led to no more than two or three days’ standing-to in readiness to support with the rest of the Brigade, and taking what odd shells fell to their share.

After this German attack, the front settled down a little, but this was only a lull before a further storm. Kipling again:

The [Irish Guards] had just been reinforced by a draft of 107 men and 4 officers— Captain Eric Greer, Lieutenant Blacker-Douglass, 2nd Lieutenant R. G. C. Yerburgh, and 2nd Lieutenant S. G. Tallents.

Above: Lieutenant Blacker-Douglass. Image from de Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour.

They were under orders to move up towards the fighting among the brick-fields which had opened on the 25th, and had not ceased since. Unofficial reports described the trenches they were to take over as “not very wet but otherwise damnable,” and on the 30th January the Battalion … moved … to Cuinchy. Here the Coldstream took over from the 2nd Brigade the whole line of a thousand yards of trench occupied by them; the Irish furnishing supports. The rest of the Brigade, that is to say, the Herts Territorials, the Grenadiers, and the 3rd Coldstream were at Annequin, Beuvry, and Béthune.

… The centre of their line consisted of a collection of huge dull plum-coloured brick-stacks, mottled with black, which might have been originally thirty feet high. Five of these were held by our people and the others by the enemy—the whole connected and interlocked by saps and communication-trenches new and old, without key or finality. Neither side could live in comfort at such close quarters until they had strengthened their lines either by local attacks, bombing raids or systematised artillery work. “The whole position,” an officer remarks professionally, “is most interesting and requires careful handling and a considerable amount of ingenuity.”

Early in the morning of the 1st February a post held by the Coldstream in a hollow near the embankment, just west of the Railway Triangle—a spot unholy beyond most, even in this sector—was bombed and rushed by the enemy through an old communication-trench. No. 4 Company Irish Guards was ordered to help the Coldstream’s attack. The men were led by Lieutenant Blacker-Douglass who had but rejoined on the 25th January. He was knocked over by a bomb within a few yards of the German barricade to the trench, picked himself up and went on, only to be shot through the head a moment later. Lieutenant Lee of the same Company was shot through the heart; the Company Commander, Captain Long-Innes, and 2nd Lieutenant Blom were wounded, and the command devolved on C.Q.M.S. Carton, who, in spite of a verbal order to retire “which he did not believe,” held on till the morning in the trench under such cover of shell-holes and hasty barricades as could be found or put up.

Above: Lt. Lennox Lee-Lee. Image from de Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour

The Germans were too well posted to be moved by bomb or rifle, so, when daylight showed the situation, our big guns were called upon to shell for ten minutes, with shrapnel, the hollow where they lay. The spectacle was sickening, but the results were satisfactory. Then a second attack of some fifty Coldstream and thirty Irish Guards of No. 1 Company under Lieutenants Graham and Innes went forward, hung for a moment on the fringe of their own shrapnel—for barrages were new things—and swept up the trench.

Many acts of bravery were carried out, some of these being detailed in 'Deeds That Thrill the Empire'.

On February 1st 1915, a fine piece of work was carried out by the 4th (Guards) Brigade in the neighbourhood of Cuinchy, where fierce had been in progress for some days. Very early in the morning the Germans made a determined attack in considerable force on some trenches near the La Bassée Canal, occupied by a party of the 2nd Coldstreams, who were compelled to abandon them. A counter attack by a company of the Irish Guards and half a company of the Coldstreams, delivered some three quarters of an hour later, failed to dislodge the enemy, owing to the withering enfilading fire which it encountered. But about ten in the forenoon our artillery opened a heavy bombardment of the lost trenches, which is described by General Haking, by whose orders it was undertaken, as “splendid, the high explosive shells dropping in the exact spot with absolute precision.” This successful artillery preparation, which lasted for about ten minutes, was immediately followed by brilliant bayonet charge made by about fifty men of the 2nd Coldstreams and thirty of the Irish Guards. The Irish Guards attacked on the left, where barricades strengthened the enemy’s position […] but the Coldstreams also had their heroes that day, and amongst them a young Yorkshire man. Private Duncan white, whose action, if necessarily overshadowed by that of O’Leary, was nevertheless, a most gallant one.

Private White was one of a little party of bomb throwers who led the assault, and on Captain Leigh Bennett, who commanded the Coldstreams, giving the signal for the charge by dropping his handkerchief, he dashed to the front and, passing unscathed through the fierce rifle and machine gunfire which greeted the advancing Guardsmen, got within throwing distance and began to rain bombs on the Germans with astonishing rapidity and precision.

Above: Captain Leigh Bennett. Image from de Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour

High above the parapet flew the rocket like missiles, twisting and travelling uncertainly through the air, until finally the force equilibrium supplied by the streamers of ribbon attached to their long sticks asserted itself, and they plunged straight as a plumb line down into the trench, exploding with a noise like a gigantic Chinese cracker and scattering its occupants in dismay. So fast did he throw, and so deadly was his aim that the enemy, already badly shaken by our artillery preparation, were thrown into hopeless disorder; and the Guardsmen had no difficulty in rushing the trench, all the Germans in it being killed or made prisoners. A party of the Royal Engineers with sandbags and wire, to make the captured trench defensible, had followed the attacking infantry. Scarcely had they completed their task, when the German guns began to shell its new occupants very heavily; but our men held their ground, and subsequently succeeded in taking another German trench on the embankment of the canal and two machine guns. Private Duncan White, whose home is at Sheffield, was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his gallantry and skill, as also were Privates F Richardson, S B Leslie and J Saville, of the same regiment.

How Private Duncan White And Other Men of The 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards Won The D.C.M. At Cuinchy. Extracted from Deeds That Thrill The Empire . Besides the Distinguished Conduct Medals awarded to White, Richardson, Leslie, and Saville, there was a further prestigious award made – that of the Victoria Cross, to a member of the Irish Guards. The following is extracted again from Deeds That Thrill The Empire:

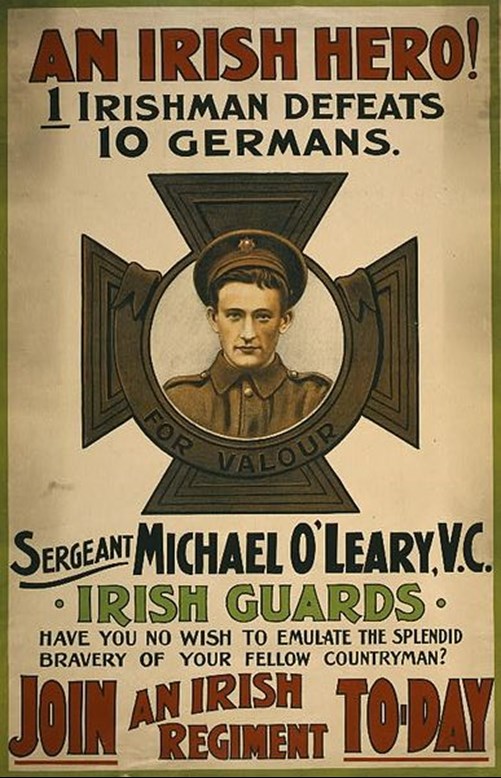

Before the Great War was a month old the critics and all the experts had formally decided that men had ceased to count. They were never tried of telling us that it was purely an affair of machines of scientific destruction, and that personal courage was of no avail. Gone were the days of knightly deeds, of hair’s breadth adventures, of acts of individual prowess. They told us so often and with such persistence that we all began to believe them, and then one day the world rang with the story of Michael O’Leary’s great exploit, and we knew that the age of heroes was not yet passed. Once more science had been dominated and beaten by human nerve and human grit.

Above: Michael O’Leary, VC.

The school for heroes is not a bed of roses and O’Learys was no exception. He was in the Navy, then he served his time in the Irish Guards, and after his seven years he went to Canada and joined the Northwest Mounted Police. By this time he was twenty-five he had sampled most of the hardships that this soft age still offers to the adventurous and given proof of the qualities which were to make him one of the outstanding figures of the “Great Age.” A long and desperate fight with a couple of cutthroats in the Far West had revealed him to himself and shown his calibre to his friends. The “Hun-tamer” was in the making.

On mobilization in August O’Leary hastened to rejoin his old regiment, and by November he found himself in France with the rank of lance corporal. His splendid health, gained in the open air life of the Northwest, stood him in good stead during the long and trying winter; but the enemy, exhausted by their frantic attempt to “hack away” through to Calais, gave little trouble, and O’Leary had no chance to show his metal. With the spring, however, came a change, and there was considerable “liveliness” in that part of the line held by the Irish Guards. The regiment was holding important trenches at Cuinchy, a small village in the dull and dreary country dotted with brickfields, which lies south of the Bethune-La Bassée Canal. On the last day of January the Germans attempted a surprise against the trenches neighbouring those of the Irish Guards. The position was lost and was to be retaken so that the line should be re-established. There was much friendly rivalry between the Irish Guards and the Coldstreams, who had lost the ground; but at length it was decided that the latter should lead the attack, while the Irish followed in support.

The morning of February 1st, a day destined to be a red-letter day in the history of the British soldier broke fine and clear, and simultaneously a storm of shot and shell descended on the German trenches, which were marked down for recapture. For the wretched occupants there was no escape, for as soon as a head appeared above the level of the sheltering parapet it was greeted by a hail of fire from the rifles of our men. O’Leary, however, was using his head as well as his rifle. He had marked down the spot where a German machine gun was to be found, and registered an inward resolve that that gun should be his private and peculiar concern when the moment for the rush came. After a short time the great guns ceased as suddenly as they had began, and with a resounding cheer the Coldstreams sprang from the trenches and made for the enemy with their bayonets. The Germans, however, had not been completely annihilated by the bombardment, and the survivors gallantly manned their battered trenches and poured in a heavy fire on the advancing Coldstreams. Now was the turn of the Irish, and quick as a flash they leapt up with a true Irish yell. Many a man bit the dust, but there was no holding back that mighty onslaught which swept towards the German lines. O’Leary, meanwhile, had not forgotten his machine gun. He knew that it would have been dismantled during the bombardment to save from being destroyed, and it was a matter of lie and death to perhaps hundreds of his comrades that he should reach it in time to prevent its being brought into action. He put on his best pace and within a few seconds found himself in a corner of the German trench on the way to his goal.

Above: A highly imaginative illustration of O'Leary's actions from 'Deeds That Thrill The Empire'

Immediately ahead of him was a barricade. Now a barricade is a formidable obstacle, but to O’Leary, with the lives of his company to save, it was no obstacle, and its five defenders quickly paid with their lives the penalty of standing between an Irishman and his heart’s desire. Leaving his five victims, O’Leary started off to cover the eighty yards that still separated him from the second barricade where the German machine gun was hidden. He was literally now racing with death. His comrade’s lives were in his hand, and the thought spurred him on to superhuman efforts. At every moment he expected to hear the sharp burr of the gun in action. A patch of boggy ground prevented a direct approach to the barricade, and it was with veritable anguish that he realized the necessity of a detour by the railway line. Quick as thought he was off again. A few seconds passed, and then the Germans, working feverishly to remount their machine gun and bring it into action against the oncoming Irish, perceived the figure of fate in the shape of Lance-Corporal O’Leary, a few yards away on their right with his rifle levelled at them.

The officer in charge had no time to realize that his finger was on the button before death squared his account. Two other reports followed in quick succession and two other figures fell to the ground with barely a sound. The two survivors had no mind to test O’Leary’s shooting powers further and threw up their hands. With his two captives before him the gallant Irishman returned in triumph, while his comrades swept the enemy out of the trenches and completed one of the most successful local actions we have ever undertaken. O’Leary was promoted sergeant before the day was over.

The story of his gallant deed was spread all over the regiment, then over the brigade, then over the army. Then the official “Eye-witness” joined in and told the world, and finally came the little notice in the Gazette, the award of the Victoria Cross, and the homage of all who know a brave man when they see one.

How Lance-Corporal O’Leary, of The Irish Guards, Won The V.C. at Cuinchy Extracted from Deeds That Thrill the Empire

Above: Michael O’Leary’s exploits were used to boost the recruiting effort in Ireland.

There are three Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries today in or near Cuinchy. Firstly, Cuinchy Communal Cemetery (photo below) contains, besides civilian graves, a total of 103 First World War graves, including 12 men from the Irish Guards who were killed on 1 February 1915, plus fourteen men from the Coldstream Guards who died on the same day.

Guards Cemetery, Windy Corner (photo below) is named after a crossroads, nearby the crossroads was a house which was used as a battalion headquarters and a dressing station. Inevitably the men who died at the dressing station were buried next to the house, this became Plots I and II part of Plot III of the cemetery which was started by the 2nd Division in January 1915. The cemetery now contains nearly 3,500 burials, the majority of which are unidentified.

Finally there is the small Woburn Abbey Cemetery. This is about 500 yards behind the where the front line trenches were located. Again, this is named after a house used as a Battalion Headquarters and a Dressing Station. The Cemetery was begun by the Royal Berkshire Regiment in June 1915 and now contains over 550 graves, of which 315 are identified.

Above: Woburn Abbey Cemetery, Cuinchy

Article by David Tattersfield, Development Trustee