The Controversy of Commemoration in Ramsbottom after the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Controversy of Commemoration in Ramsbottom after the First World War

War memorials are contentious: the commissioning of large public sculptures has often divided communities, with stories of bitter discord surfacing both during the Great War and in the years that followed.

Disputes about the control of war memorial committees, as well as the decisions made by them, often made local newspaper headlines. The main criticism was that wealthy individuals or small groups made up of‘ the great and good’ of their local communities – the social and political elites who had usually been too old to serve – were monopolising the decision making.

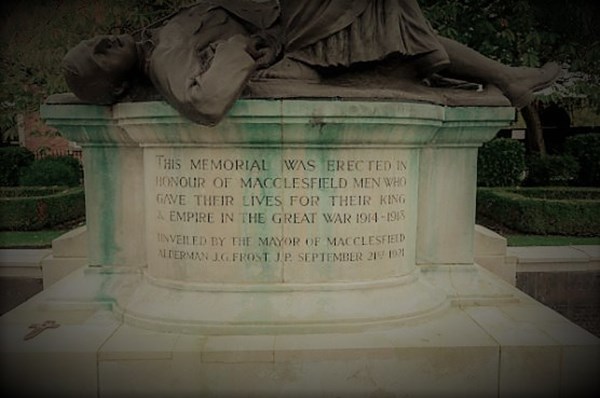

This was certainly the case in Macclesfield, Cheshire, where the committee was dominated by elderly worthies who even rejected a proposal that bereaved families and veterans should be consulted on what they might want to see erected. Local veterans’ associations in the area would be further enraged to discover that the town Mayor (Alderman Frost)had chosen himself to unveil the memorial and lay the first wreath - and that this was not up for debate because the engraving saying that he had done so had already been cut into the memorial by the masons.

Above: The unveiling of the Macclesfield memorial in 1921, the central stone that records for posterity the Mayor’s role at the ceremony, and (below) the site as it looked more recently (Macclesfield Park Green VE Day 2015) Photographed by Rosie Rowley (c) 2015

Among the most bitter of battles was a dispute at Stoke Newington in which it was decided that only those in a position to make a financial donation to the new memorial be allowed to attend a public meeting to discuss what form it might take.

Unsurprisingly, when members of the public and veterans’ associations felt left out of the process, their levels of interest, which had often started very high, would fade. For example, just 20 people made the effort to show up to see the famous sculpture Sir Reginald Blomfield reveal his plans for a civic memorial in Leeds after the public felt that they had been left out of the process.

Above: Renowned architect Sir Reginald Blomfield found that he had stepped into an unhappy situation when he arrived to unveil his plans for the civic memorial in Leeds.

There were numerous stories of a similar nature around Britain in the postwar years, and one of the longest-running disputes appears to have involved the small mill town of Ramsbottom in Lancashire.

Whilst tensions generally fade with time, recent moves to change the remembrance infrastructure at Ramsbottom have illustrated how old debates can easily reignite and how important it is to do your history before trying to impose change.

The Ramsbottom story is tied to the to the centenary of the First World War, when plans were announced to ‘improve’ the commemorative infrastructure. The scheme was the brainchild of a small group of local individuals, and their plan to add a memorial wall to complement the existing memorial – one that could carry the names of the local fallen of both world wars.

This proposal was welcomed, and donations already running into the tens of thousands when the organisers (seemingly unhappy with the site being offered for the memorial wall by the custodians of the site)decided to change course. Their new plan was to remove the existing war memorial and re-site it in a graveyard more than a mile away so that it could be replaced with something far ‘grander’ that could carry the names of the fallen.

It was a decision taken without consultation and, most importantly, with little or no knowledge of the history of the plot or what it revealed about the people who put it there.

Above: The memorial gardens at St Paul’s Church in the centre of the town of Ramsbottom prior to the ‘improvements’ and (below) a recent image of the cleaned memorial, cut-back planting and new memorial panels

For the story of commemoration in Ramsbottom is complex: whilst nearly every community in Britain had raised funds for a town memorial after the First World War (in addition to numerous smaller ones in workplaces, schools, churches etc), Ramsbottom had not done so.

It was not until 20 years after the Armistice (in 1938) that the community finally agreed to establish a memorial garden at the heart of the town in front of the parish church. Furthermore, the garden that was created did not have any military statues or symbolism but was instead a simple and well-tended plot of attractive planting where people could sit and quietly reflect on their losses.

The decision to erect a more formal memorial statue in the garden was taken after the end of the Second World War. Unveiled in 1950, it was relatively small within the wider context of the garden– presumably so that it did not dominate it. In addition, the statutory was a straight replica of the plain memorial crosses found in most Commonwealth War Grave Commission cemeteries overseas, rather than the more individualistic kind of memorials often seen in communities of a similar size to Ramsbottom. Was this modest memorial a further compromise and reflection of ongoing tension?

Research into why the people of Ramsbottom made the decisions they did is ongoing, with one line of inquiry being that it might be related to a relatively high level of Methodism and conscientious objection in the district at the time. Local newspaper coverage was surprisingly limited, but whatever the reasons - be they economic, personal, religious or political - the infrastructure at the memorial garden was a reflection of the way the people of the community had decided to express their grief, heal their wounds, and remember those they had lost.

Concerns about the centenary proposals at Ramsbottom would ultimately reach English Heritage, which carried out its own study and opted to place the protection of ‘Grade II Listed’ status on the existing memorial –protecting it for perpetuity.

The result? The process of ‘rejuvenating’ the Ramsbottom remembrance garden and memorial was returned to its original focus of enhancing what was already there; albeit still including the placing of stone panels (carrying the names of the fallen) around the base of the existing memorial.

When the new and cleaned stonework has had time to weather and more substantive planting been added, it is to be hoped that the ‘revamped’ memorial site will be able to continue to honour the town’s fallen in a way that honours its fascinating and still unravelling past.

Article by Dr Martin Purdy