The Envelope in the Attic : Items pertaining to Private Arthur W. Holtby of the Canadian Expeditionary Force

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Envelope in the Attic : Items pertaining to Private Arthur W. Holtby of the Canadian Expeditionary Force

[This article first appeared in the June/July 2007 Edition of Bulletin No.78]

Whilst looking for genealogical documents and family pictures in the attic of his parents’ house in England, Glen Martin of Staffordshire found an envelope, which had not been opened since his paternal grandparents’ time.

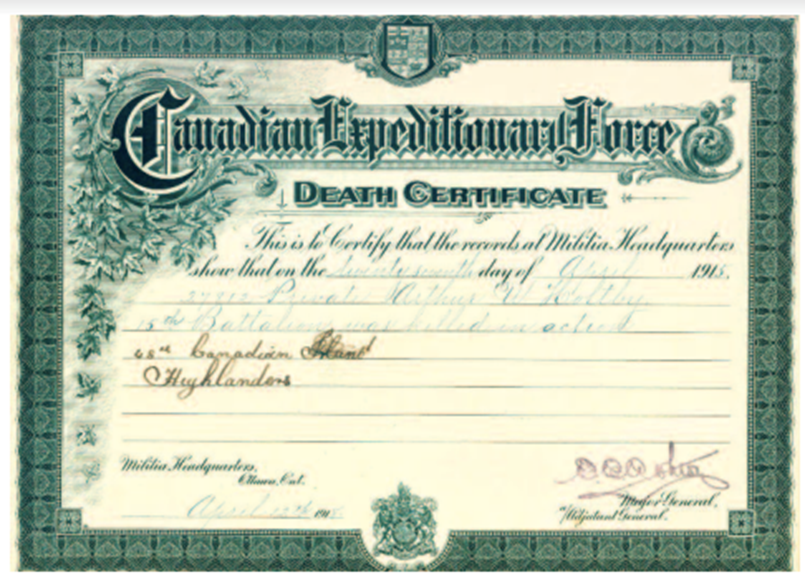

The envelope contained four intriguing documents: a picture of a young man in civilian clothes, a Certificate of Death issued at Militia Headquarters in Ottawa, Canada, a copy of the Menin Gate Memorial Register, and a letter of condolence written in pencil on 27 April 1915 by Battery Sergeant Major Deeks of the 69th Battery, Royal Field Artillery. The letter and Death Certificate referred to Private Arthur W. Holtby 27812, 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF).

The writing in the letter was faint but legible. It read as follows: 27-4-15

Dear Mrs Holtby,

Having paid the last respects to your son, I thought you would like to hear that he died in action so I saw him laid to rest and have erected a small wooden cross over his grave. Am sending you a photo I found on him & his letters. I will burn unless I hear from you, as we cannot send a parcel from here. Suppose you will hear from others sooner but thought you would like a line from one who saw him & I always feel so sorry for the poor mothers in England who really have a far harder time than us. So please accept the sincerest sympathy of one of the lads at the front. I must conclude, as time is so precious. From yours truly

Battery Sergeant Major Deeks

69th Battery R.F.A.

28th Division B.E.F.

Mrs. Charlotte Holtby, to whom the letter was addressed, was Glen Martin’s paternal great-grandmother and Arthur Holtby was her son. Glen was aware that he had a distant relative who died in the Great War while serving with the Canadians but nothing more. His grandmother, Arthur’s youngest sister, had mentioned this to him when he was a very young boy. Glen’s father knew a little more about Arthur but not that he had died in action during the Second Battle of Ypres and was commemorated on the Menin Gate. Glen at the time had no great interest in the First World War beyond the family connection.

Mrs. Charlotte Holtby, to whom the letter was addressed, was Glen Martin’s paternal great-grandmother and Arthur Holtby was her son. Glen was aware that he had a distant relative who died in the Great War while serving with the Canadians but nothing more. His grandmother, Arthur’s youngest sister, had mentioned this to him when he was a very young boy. Glen’s father knew a little more about Arthur but not that he had died in action during the Second Battle of Ypres and was commemorated on the Menin Gate. Glen at the time had no great interest in the First World War beyond the family connection.

This intriguing material made him want to learn more. Where could he find information?

The Internet has greatly increased the availability of documents relating to the Great War, and the Canadian government has led by scanning individual Attestation Papers and battalion War Diaries of the CEF. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) has put online the names of all the men and women whose graves are under its jurisdiction. By going to the CWGC site Glen learned that Arthur was 24 when he died and in addition to the 15th Battalion and the 48th Highlanders of Canada he was also listed as a member of the Central Ontario Regiment.

Glen found the website of the Central Ontario Branch of the Western Front Association (www.cobwfa.ca click on RESEARCH). The Branch gets many requests from people, especially residents of the UK, seeking help in accessing and interpreting the documentation available for members of the CEF. Among the branch members are people with a lot of information about the arcane terminology and structure of the CEF. The first area of confusion for Glen was: “How could Arthur be in three different units simultaneously?”

The eccentric and controversial Canadian Minister of Militia and Defence in 1914 was Sam Hughes (later Lieutenant-General Sir Sam) who arbitrarily replaced the mobilisation plan of the Permanent Force (today called the Regular Force) with a scheme of his own. Hughes by-passed the existing militia units (today called the Reserve Force) as the basis for expansion and sent telegrams to 266 men whose military credentials he liked and authorised them to recruit overseas battalions. Most of these instant lieutenant colonels had militia experience but in only a few cases were the resulting numbered battalions allowed to keep the subsidiary name of the militia unit that had raised the overseas battalion. The 48th Highlanders of Canada, a Toronto militia unit, was one of the lucky ones. It recruited the 15th Battalion mainly from its own pre-war officers and men.

The Central Ontario Regiment is the name of the recruiting and reinforcement unit set up in March 1917 to replace the original system of raising whole battalions and then dispersing them to Reserve Battalions in the UK. From that date, new volunteers and conscripts were enrolled in these Territorial Regiments named after the provinces in which they were recruited. There were a few exceptions: for example, the 52nd Battalion (New Ontario) raised in the Port Arthur/Fort William area (now renamed Thunder Bay), at the western end of Lake Superior, was part of the Manitoba Regiment because Winnipeg, Manitoba, was the nearest town with a large enough population to supply reinforcements. After training in Canada and England the soldiers were sent as reinforcements to line battalions from the same provincial Territorial Regiment. Is it an anachronism to label a man from the 15th Battalion who was killed in 1915 as a member of the Central Ontario Regiment? The CWGC uses the designation to indicate the CEF organisation at the end of the war.

The online Canadian Expeditionary Force: Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War shows that the 15th Battalion after rudimentary training at Valcartier Camp near Quebec City arrived in Plymouth on 14 October 1914. It endured a very wet winter on Salisbury Plain before sailing to France on 15 February 1915. After a short introduction to trench warfare with British troops near Armentières, the CEF was moved north to the Ypres Salient where the British forces were taking over more of the line from the French army. Here the very green troops of the 15th Battalion took over trenches near St. Julien on the night of 21-22 April. It was a very unfortunate time for novices to be going into the line because on the afternoon of the 22nd, the Germans unleashed chlorine gas for the first time. The French colonial troops on the left flank of the CEF were hardest hit and most fled. Although missing the worst of the first gas attack on 22 April, the 15th remained in its trenches in the Apex and was badly hit by the second gas attack on 24 April and by 10:00 am was overwhelmed. Suffering 220 dead and 257 taken prisoner, the battalion ceased to exist as a fighting force and the remnants were withdrawn to the area around La Brique and Wieltje by 25 April.

The 69th Battery, RFA, was a British artillery unit firing its 18 pounder guns in support of the British and Canadian troops in the Salient from a point on the Frezenburg Ridge several kilometres from Wieltje. Two pages of the 69th War Diary are scanned into the Canadian War Diaries site.

27th [April] - Quiet. Wagon line shelled and several horses killed & wounded. Fired 180 Rounds.

28th -Wagon line shelled. Dr[iver] RICHARDSON fatally wounded. Fired 83 rounds and crumped by 5.9

29th -Dr McGuiness, Dr Markey, wounded in wagon line. Lt.Brink returned to 103rd. Fired 58 rounds

30th – Gr Wilson killed at battery. 4 limbers destroyed, owing to barn being burned. Fired 55 rounds.

On the barn catching fire, Lt.SWAIN and S.M. DEEKS, Fitter St.Sergt. BATES & Gunner MULLINS made several attempts to get into the barn to rescue the wounded, of which there were several (Infantry men) but it was impossible to enter. Gunner WILSON was apparently from his attitude when found, killed or severely wounded. His remains were burned as were those of another man (Infantry) - whose remains there were no means of identifying.

The battery sergeant major was the administrative NCO of the battery and operated at the wagon lines a kilometre or more behind the gun position. We know the position of the 69th guns near the railway embankment east of Frezenburg. We have not been able to positively locate the wagon lines but know that it was at a farm near a village. The area of La Brique-Wieltje-St. Jean seems likely. Pte. Holtby could have been one of the infantrymen who were taking shelter in the barn. However, the entry for the 27th says it was ‘Quiet’ in spite of the heavy shelling that was going on. Holtby could not have been burnt or the picture would not have survived unless his kit with the pictures was outside the barn and not damaged. The 31st Brigade RFA, to which the 69th Battery belonged, has nothing of significance for 27 April in its War Diary.

30/4/15 – 1:20 pm. Germans shelled 69th farm causing it to burn very rapidly and although every effort was made to save the limbers which were in the barn they were not saved. Two wounded infantry in the barn were saved in a serious condition. Gunner WILSON, 69th Battery, was killed in the farm.

It is tantalising to make the assumption that BSM Deeks was mistaken in dating his letter and that Pte. Holtby was one of the wounded infantry who were taking shelter in the barn on 30 April when BSM Deeks tried to rescue the wounded. Certainly there is confusion as to whether Gunner Wilson was killed at the battery or at the farm but there is no evidence that favours the assumption. Holtby, wounded and exhausted, could have stumbled on the 69th farm in the withdrawal of the 15th on 25 April and then died in the shelling. Gunner John Wilson, 69130, 69th Battery RFA, is recorded on the CWGC Roll as having died on 30 April and is commemorated on the Menin Gate. Frederick W. Deeks was a pre-war Regular in the RFA who had joined in 1905 for three years Before the Colours and nine years in the Reserve. When war broke out he rejoined his unit. Shortly after Second Ypres, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant, RFA. He died of wounds before taking up an officer’s position on 13 September 1915, age 29, and is buried in Étaples Military Cemetery.

Because Pte. Holtby had been in Flanders for such a short time, it was not surprising that his Personnel File from the National Archives of Canada added very little additional information. The 48th Highlanders Museum in Toronto checked its records and found that Arthur had joined the unit in March 1914. The 1914 Toronto Directory showed that there were several people with the surname Holtby but no one called Arthur. Genealogical research by one of Glen Martin’s relatives did indicate that Eli Holtby of the Toronto area was a half-brother of Arthur’s father. Further research may indicate that Arthur was staying with him when he joined the 48th.

The search for the location of the 69th farm continues. Glen Martin’s interest in the Great War was increased and he became a member of the WFA in December 2006.

Anyone with additional information is asked to contact gordon.mackinnon@sympatico.ca or Glen at darnford.close@virgin.net

Article by Gordon Mackinnon