The 'fake' French Aristocrat at Etaples

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The 'fake' French Aristocrat at Etaples

In the vast expanse of Etaples Military Cemetery are thousands of headstones. Each of these represents the last resting place of a casualty of the war. No doubt all stories are unique, but to misquote George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’, some are 'more unique than others'.

Above: Etaples Military Cemetery

Below is the image of a headstone of what would seem to be a young British subject who was from an aristocratic French family.

Above: The headstone at Etaples Military Cemetery. This can be located at 'LXVII G 3'.

Perhaps – we could surmise – the family came over to the UK many centuries ago and the noble name was passed down the generations. Perhaps the 19 year old William James (the cemetery register tells us his name and his age) was the last of his line?

As expected, the entry in the CWGC’s register adds further detail as follows:

DE TOLLE-SWAIN (VICOMTE DE TOLLE) Pte William James. 515203 'C' Coy 1st London Scottish. Died of injuries received in rescuing three men from drowning 13 Aug 1918 aged 19. Only son of William George and Florence L de Tolle-Swain (Comte et Comtesse de Tolle) of Bournemouth. Born at Oxford and enlisted at Bournemouth while living there.

We perhaps imagine the family being wealthy and the young man was destined for a glittering career – perhaps using his connections in the field of diplomacy.

Initial research confirms the connections with Bournemouth: the town's St Clements church war memorial (due to space restrictions) detailing him as 'WJ de T Swain'.

Above: Bournemouth St Clements War Memorial courtesy of www.roll-of-honour.com / Photograph copyright © 2004 Vernon Masterman

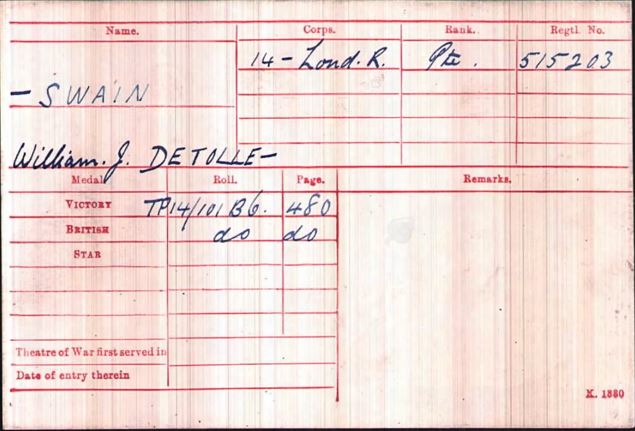

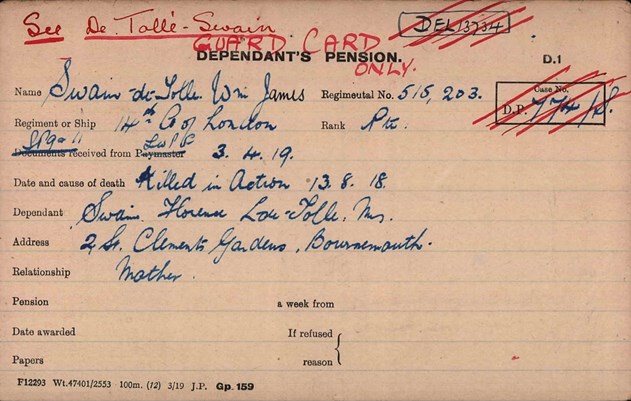

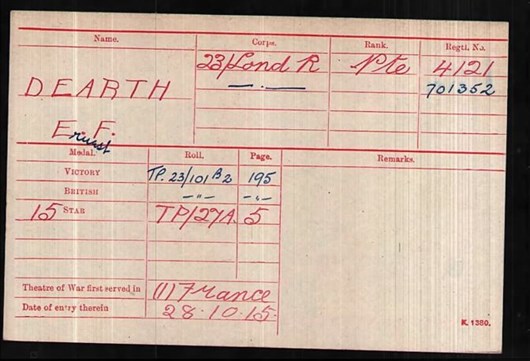

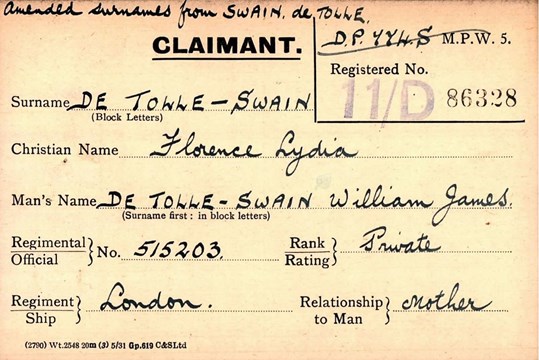

His Pension Record Card, Medal Index Card and (thankfully surviving) service record all confirm his name, without detailing his Vicomte (French Viscount) title.

As will be explained later making contact with one of his distant relatives, Naomi Lewis, has revealed a lot about his life and death, and we also have a photo of William James (for reasons that will become obvious, we will refer to this soldier as ‘William James’. His father is ‘William George’.)

Above: William James de Tolle Swain. Courtesy of Naomi Lewis

Below are the readily located records showing his pension card and medal index card. Both confirm his name in full.

Above and below: The Medal Index Card and one of the Pension Record Cards detailing William James's full name.

It seemed that this may be an interesting research project, so the authors set about this – expecting to see some sign of French aristocracy or perhaps even find the ancestral home in some medieval chateau. This indeed proved to be an absorbing project, even more so than was ever imagined.

William George Swain (the father)

Initial research showed the soldier’s parents to be William George and Florence Lydia Swain, who were married at Christchurch in Hampshire in 1894. Their daughter (Dorothy Florence) was born in 1896 and son (William James – who is buried at Etaples) was born in 1899. But the records all detail them as ‘Swain’: there is no sign of the 'de Tolle'.

Census returns tell us that in 1871, William George was an infant, living in Manor Place, Hackney, with his birthplace shown as Stoke Newington. The family had two servants - a nursemaid and a general domestic servant. By 1881, the family was living in 97 Amhurst Road, Hackney, still employing a domestic servant, with William George (aged 11) described as 'scholar' and again, William George's birthplace is shown as Stoke Newington which is in the borough of Hackney, in London.

Above: 97 Amhurst Road, Hackney

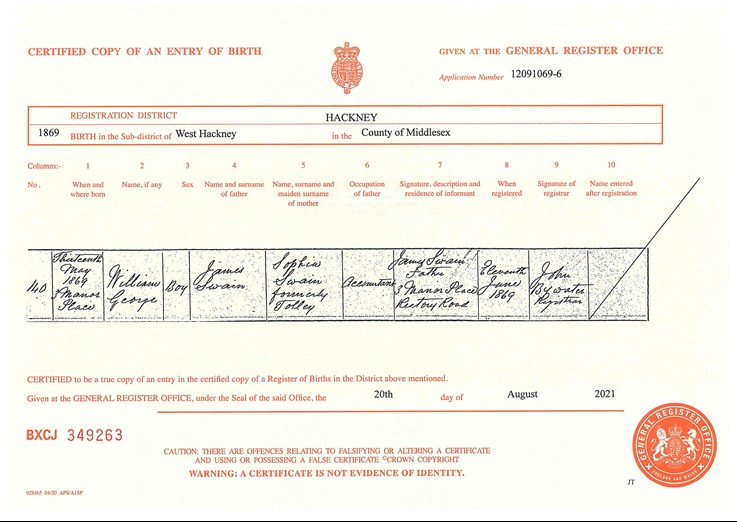

As an adult, William George can be found on the 1901 Census,[1] with his wife Florence Lydia and two children, living as lodgers at Walcot Parade, Bath. This seems to have been a move from Headington, Oxford where we know William James was baptized between January and March 1899. At this point, William George described himself as an 'accountant' and declared, surprisingly, that he was born 'at sea'. This is the first embellishment of his life in what was to prove to be a series of revelations. The significance of the (false) 'born at sea' assertion only became apparent later, as will be explained below.

Above: William George Swain's birth certificate showing he was born in Hackney, not 'at sea'. Note the mother's maiden name.

The two year old William James and four year old Dorothy were obviously not yet at school.

By 1911 the family was at Boscombe, near Bournemouth. They had a servant and two boarders. The address suggests they lived close to the sea-shore at the Marina. All very respectable. On the records so far located, there was no sign of any ‘de Tolle’ and even less sign of French aristocracy; however the link with Bournemouth is established.

Back a few generations

In search of the ‘French connection’ we are able to go back several generations. On the Swain side, there is nothing but ‘Swains’ with nothing that looks remotely like ‘de Tolle’. But an interesting discovery was made when it was found that William George’s mother came from a family line with the surname of ‘Tolley’ the earliest of whom that has been traced being Thomas Tolley (1680-1727). Is Tolley the source of the ‘de Tolle’? It certainly looks that way.

William George Swain set out his belief about his heritage in a letter written in 1918, after his son’s death. It was at this point that the discovery of a detailed public family tree on Ancestry assisted greatly in our research, with the added assistance from William George’s only surviving direct descendant Naomi Lewis. It was Naomi who provided a further explanation which appears to have been passed down through the family.

William George’s 1918 letter

His letter written to an unidentified recipient stated:

‘... my Great grandfather was, at the time of the Revolution Jerome de Tolle, Grand Duc d’Estevan – Estevan being in Alsace so that by the German occupation in 1870 it is doubly lost to us. The old man like so many others having lost both estates & income went into trade & they wisely dropped the title (having no money to support it) using the name of Toley or de Tolle, both forms being equally used in France. That is why we perpetually wait for an overthrow of the Republican party in France & long to see Alsace Lorraine free from Germany. That is one reason why Boy [William James, his son] wanted to chuck up trade & return to something nearer his proper position in life.'

Comment: On the Swain side of the family, there is nothing that looks remotely like ‘de Tolle’, but William George’s mother’s maiden name was Tolley, the earliest of whom has been traced as being Thomas Tolley (1680-1727) – all ancestors being born in England.

The family 'legend’

Naomi, who is William George’s direct descendant provided a further story that had been passed down in the family. The legend states that William George’s mother (Sophia Swain, née Tolley) had worked as a governess for the exiled Louis Philippe, Duc’d’Orleans, whilst her husband was away at sea and became pregnant by Louis Philippe. When her husband returned, he took his wife on a voyage, where she gave birth to William George.

Comment: whilst Louis Philippe was living at York House, Twickenham at the time of the 1871 Census, his young children were not at an age to require a governess. Indeed, the family employed three nursery maids in 1871. Louis Philippe also had a son, born before William George Swain, therefore, even if true, the title would have passed to his son, and not William George. Finally, William George's mother already had a young child and it might therefore be unlikely that a married woman with a child would be employed as a governess.

Above: Philippe d'Orléans, comte de Paris who died at Stowe House in 1894.

Why, then, the embellishment to the original surname?

Obtaining credit by false pretences

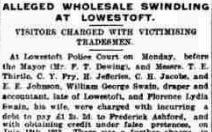

One possible explanation for this subterfuge became apparent after some digging around. It would seem that William George and his wife, with the two children in tow, undertook a prolific series of small scale frauds along the south coast and elsewhere between 1909 and 1913. Given the suggestion that William George was an accountant, the basic nature of this criminality seems very unsophisticated and may well have lasted for a longer period than detailed in the accounts shown below..

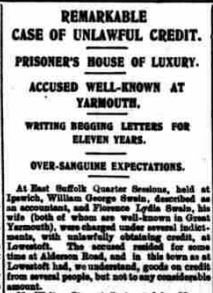

Above: Headlines from some of the newspapers detailing the court appearances (British Newspaper Archive).

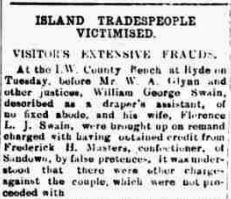

Isle of Wight Observer 14 May 1910.

"William George Swain (a draper’s assistant) and his wife Florence were charged with having obtained credit from Frederick Masters, confectioner, by false pretences. Other charges were not proceeded with. It seems that in late April, Florence rented a two bedroom apartment and a fortnight’s rental was agreed. No luggage was delivered which aroused the landlady’s suspicion and she asked for some of the rent in advance. They stayed for four nights and then decamped. But during this time food was delivered from local shopkeepers.

"A few days later, after making enquiries, the police found the family in another house eating lunch. Asked her name, Florence said ‘Mrs Jarrett' at which point William George tried to take full responsibility and persuade the police that it was all his doing. At the police station William George said he’d come to the Isle of Wight in search of work, but could not provide details of any applications for work. At this point they gave their real name of Swain and Florence said 'Jarrett' was her maiden name [which we know is indeed the case]. When asked about similar incidents at Yarmouth, Seaview [a small village on the Isle of Wight] and Cowes they admitted going to these places and incurring debts.

"On being charged, William said he had been out of work and had to live and it was either this or the workhouse which would have meant he would not have been able to undertake his business. As the case unfolded, other incidents at Ryde, Sandown and Carisbrooke were mentioned. They also ‘came under the notice of the Brighton police in 1907’. Where it seems William George had written begging letters to his firm’s clients. Further incidents at Buxton [this may be a typo for Buxted], Hastings, Bexhill and Canterbury were mentioned.

"William George was sentenced to six weeks hard labour and Florence was bound over for six months."

The Diss Express and Norfolk and Suffolk Journal – 21 February 1913; Lowestoft Journal – 22 February 1913

These three newspapers reported a further brush with the law three years later. William George Swain and his wife Florence Lydia were charged with having incurred a debt of £1 2s and 6d by unlawfully obtaining credit in July 1912 but having absconded before any trial. The report says ‘there were a number of similar charges affecting other tradesmen’. These seem to have occurred between July and October 1912. The total debt involved being said to be £88. To put this into context, this would work out as over £10,000 in today’s money. The method described in the newspaper was much the same as that detailed on the Isle of Wight, this time stating they were looking for business premises to open a shop. It seems Florence took Dorothy (who would have been 17 years old) to buy blouses on credit and even hired a ‘fancy goods shop’ at which they sold goods they had obtained. ‘Having sold the goods they went away’. The charges brought related to events in 1912 but others from 1913 seem not to have been brought.

Yarmouth Independent 19 April 1913; East Kent Times – 23 April 1913

Reporting on the same set of offences as above, these newspapers bring the story up to date and add that William George was an ‘Accountant and Draper’. They describe how he and Florence targeted small traders and add other locations, including events at Ramsgate and Margate. Dovercourt (in Essex) and Felixstowe were other towns where they operated. They then followed up at Lowestoft and Cromer. From here they seem to have proceeded to Yarmouth ‘where they spent the months of December and January’ (presumably 1912/13) ‘getting newspapers, fancy articles and confectionery delivered to them. They returned to Lowestoft which may have been how they were caught.

The lawyers pointed out many of the victims were widows who let rooms. A weak defence was put up with William George saying he endeavoured to work by travelling in the drapery trade and that since he married his wife ’20 years ago’ (which was broadly accurate) he had suffered from ill health from being partially paralysed through falling from the top of cliffs at Bournemouth. He had not been successful in business and the credit he obtained was in respect of necessaries of life. He was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment with hard labour. Florence was formally discharged.

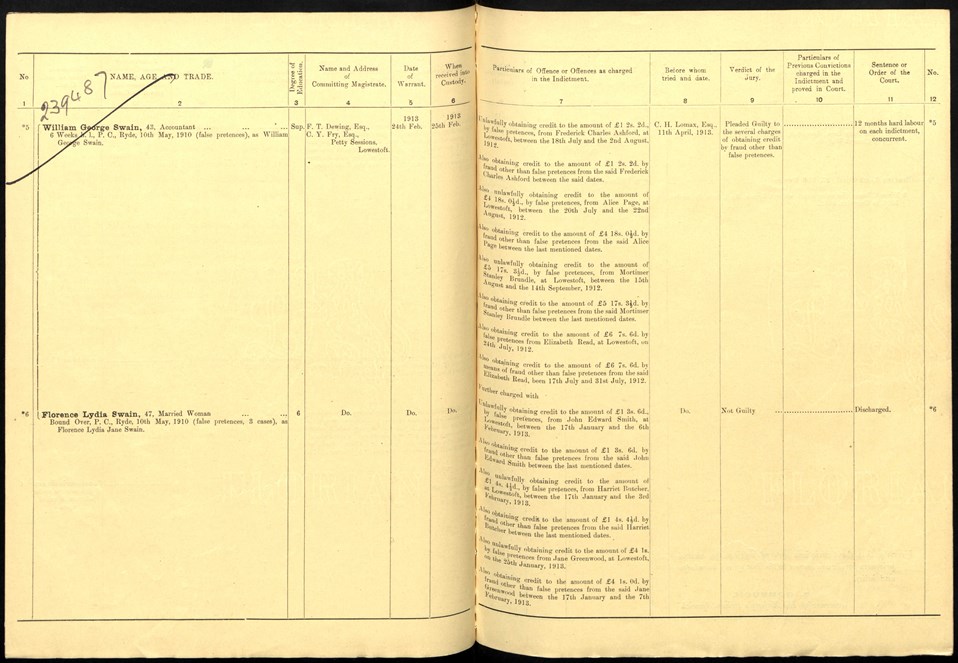

The details of the court can be found online. It seems that in the Lowestoft Petty Sessions on 11 April 1913 William George pleaded guilty to after being charged with eight sample offenses of unlawfully obtaining credit by false pretences,[2] and for obtaining credit by fraud other than false pretences from four individuals.

Florence Lydia was found not guilty of unlawfully obtaining credit by false pretences and for obtaining credit by fraud other than false pretences from three individuals.

Florence was discharged following the verdicts. Below is the document showing the charges and verdict.[3]

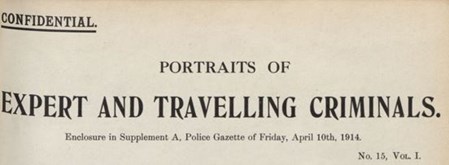

A further report detailing William George's activities has been found - together with a mug shot which makes it clear the above was likely just the tip of the iceberg.

Above: The 'mugshot' of William George Swain from the Police circular dated 10 April 1914

The detail is as follows:

William George Swain alias Jarrett born London 1869; height 5ft 6in... Convicted at Ipswich Sess[ions] 11 April 1913 and sentenced to 12 months... Liberated 10 February 1914 when he expressed his intending to proceed to Bournemouth. Previously convicted of similar offence at Ryde.

Method: Although only twice convicted this man is a confirmed swindler and has been living practically by this means for the past dozen years. Of smart appearance and refined manners he, with his wife (Florence L J Swain, who has been convicted with him), and two children - a boy and girl aged, respectively 15 and 17 - visits seaside resorts and towards the evening calls at houses where apartments are advertised to be let. Rooms are engaged, generally for a month, for which he agrees to pay at the termination of his visit, and he then systematically victimises all the tradespeople with whom he has dealings; supplies, wearing apparel etc being obtained on credit, payment rarely, if ever, being made. This he carries on as long as expedient and absconds without settling for his apartments, to another town, where he resumes his fraudulent practises. While in custody at Lowestoft it was ascertained that he had committed offenses at Bungay, Christchurch, Brighton, Hove, Hastings, Bexhill, Eastbourne, Ryde, Deal, Ramsgate, Margate, Herne Bay, Dovercourt, Felixstowe, Cromer and Great Yarmouth, the amount involved being approximately £250.[4]

The sums involved in the above report would be approaching £30,000 today. The use of an alias (of Jarrett - being Florence's maiden name) suggests intent and fore-thought.

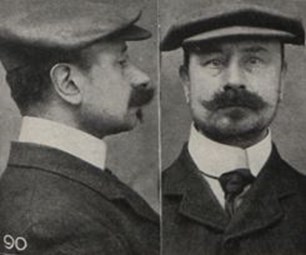

So far, we have not ascertained what William George did after his release from prison, although one clue as to his employment can be seen on his national registration card shown below.[5]

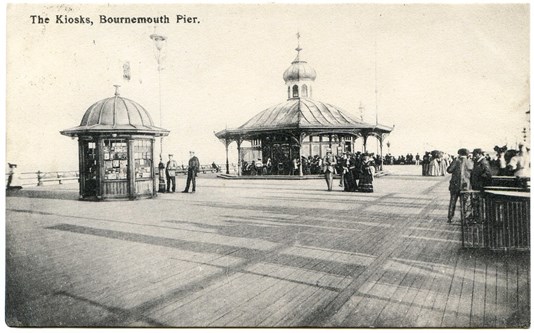

The above card, which refers to him being the manager of the 'Pier Book Kiosk' and 'Post office sorter for the night mails', suggests he found employment after his release from prison.

Above: Is this the book kiosk of which William George was 'manager' in 1915?

War broke out. William George was too old to serve in the armed forces, but William James, we know, was old enough to be conscripted in due course, which is detailed below.

Reinvention

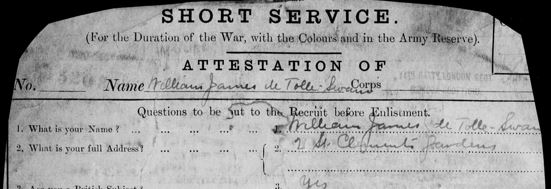

Other than the National Registration card mentioned above (which is undated), the first evidence of the reinvention of the couple as ‘de Tolle-Swain’ can be found on William James’s army attestation papers when we see him enlisting under this name, and his father – William George – also being detailed under the ‘new’ family name.

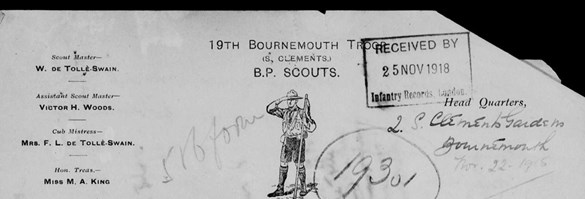

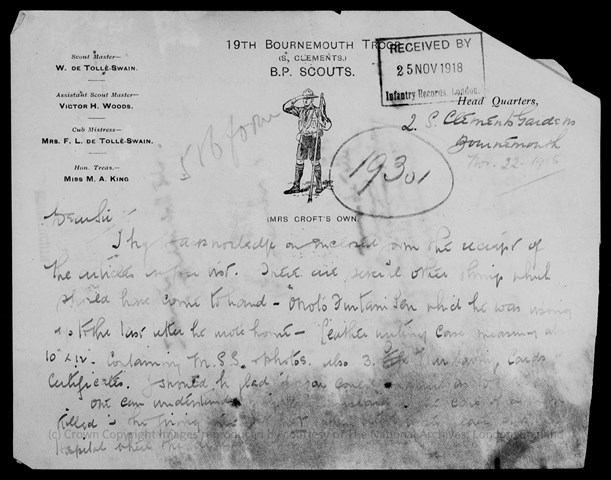

There is also evidence of the new name on a letterhead dated 1918 of the 19th Bournemouth Scout Troop. We will return to this letter later.

William James - Jeweller's Assistant

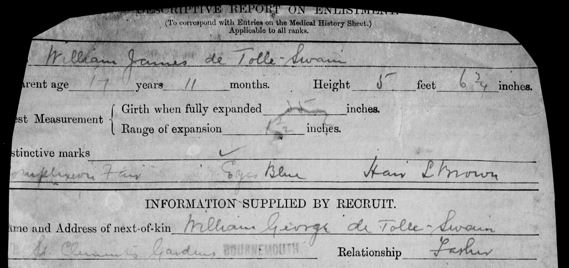

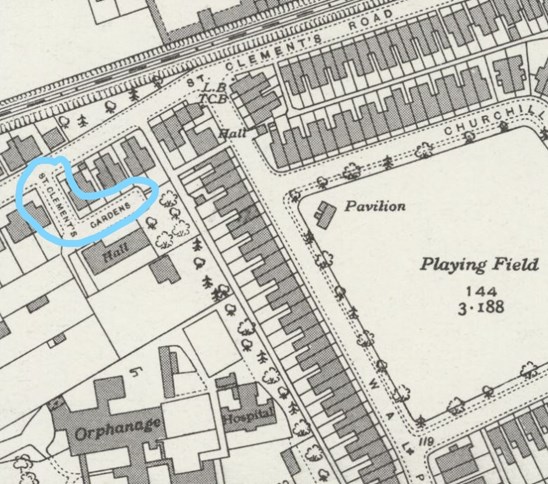

On 29 January 1917 at the age of 17 years and 11 months William James – using the family’s ‘new’ name of de Tolle-Swain – went to the local recruitment centre and attested. He was living with his father (and presumably his mother) at 2 St Clements Gardens, Bournemouth.

Above and below: St Clement's Gardens today (Google street view)

Above: an inter-war map showing St Clement's Gardens

The young William James was described as a ‘Jeweller's Assistant’. His papers tell us he was 5’6¾”tall with light brown hair and blue eyes. As was routine he was put to the Army reserve and mobilized on 7 March 1917 (when he was 18 years old). From this point he was assigned to the London Regiment‘s 14th Reserve battalion.

Above: Shoulder badge of the London Scottish.

Above: A group of men from the 14th London Regiment (London Scottish) on route march Aldershot area (possibly 1914)

Above: Recruits having their service uniforms fitted. Probably taken 1917. IWM Q30069.

As can be seen from this and other correspondence he was known to the family as ‘Boy’.

London Scottish, Chisledon Camp, Wilts.

5/1/1918

Dear people,

You see I have been discharged from hospital at last, and to a hell-hole – when we were at Winchester we thought it bad enough but ye gods, this place is hell, a vermin and damp infested camp that was condemned when the first of Kitchener’s army took it over and now has a 20% sick list, and is over six miles from a town. Thank the Lord that I have hospital leave to come and may be home any day as it was I took one day on my own after discharge from hospital on the morning of the 2nd and did not report here until late on in the night of the 3rd but as they did not find out it did not matter, yes what a contrast to London life with lunches at the Trocadero and Waldorf and theatres in the afternoon.

And now this hole. Wellwell it is a great life in the army. Thank goodness I am nearly 19 for France though uncomfortable is for some good and I have had long enough hanging about here in England. All I want is to get out and get a “blighty” one that will keep me in hospital for the duration, or get my ticket, however as I say I hope to be home soon, at present I am hanging around in camp unfit for duty and as my hospital papers have not yet come to hand, unable to draw any pay although they owe me about six pounds. If I can draw about half or so when I get my leave, I shall not mind but I think they might “fork out” now, however keep smiling. I hold a few trump cards yet, which by the way reminds me that at our whist drive on Xmas day I won a pigskin letter case, quite a good thing too. On ???? night we had a very fine pint at Kensington Town Hall as I probably told you in my last letter. I got home at 2.30 but did not get up until 8.30 the next morning and went out for a motor drive all round Richmond and Wimbledon with a friend, and now at hell in this hole. I have however found one clean dry spot in camp where one can obtain ??? and refreshment including rump steak and whisky, namely the RC’s Padre’s bunk and here I sit writing while the steak sizzles on the fire and I have a hunger so will close this epistle and hold over all the charming details of my chequered career till the next anon.

Yours

Boy

Above: An undated letter, probably prior to him being deployed to France. Courtesy of Naomi Lewis

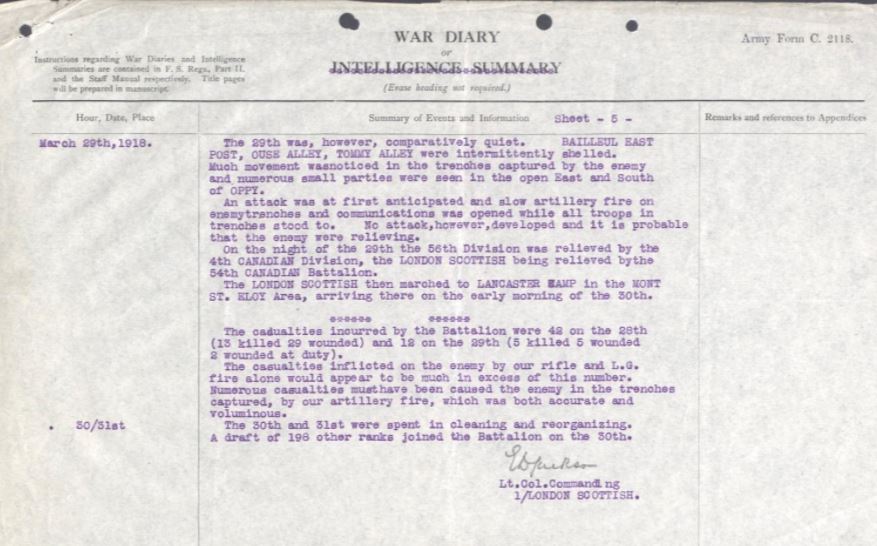

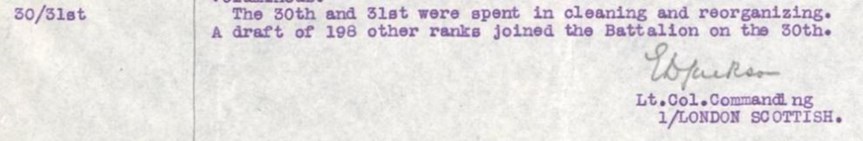

He seems to have proceeded overseas to France on 29 March 1918 joining the 14th (London Scottish) battalion of the London Regiment. The war diary does give details of a draft of men joining and more than likely arrived with a large draft on 30/31 March 1918. Below can be seen the reference in the battalion’s war diary (TNA WO 95/2956).

A close up of the last lines shows this in more detail.

As is usual, there are clues as to what action he saw, but the battalion did see some action on 19 April and incurred casualties. Although we can’t be certain, it’s likely that William James de-Tolle Swain was in action, but unwounded on this day.

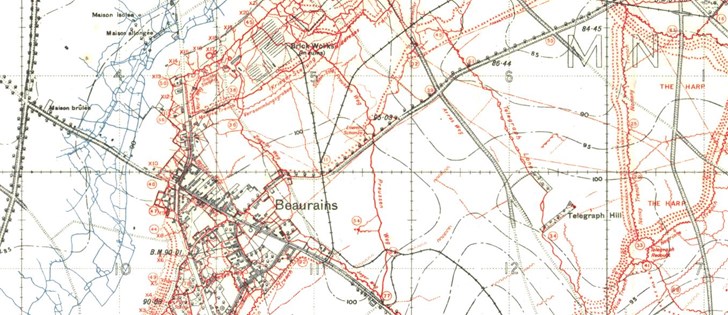

19 April

The operation on the 19 April by the London Scottish is covered in great detail in the battalion’s war diary. The intention was to create an outpost line in front of some poor quality trenches the division (56th (London)) had just taken over. This was in the area between the Arras-Neuville Vitasse road and the Arras–Beaurains road just to the east of Arras. The battalion’s ‘C’ Company was to lead the attack. It should be noted that this was William James’s company.

Above: A trench map from November 1917 showing Beaurains, just outside Arras (Great War Digital)

In a driving hail storm which helped mask the operation, the company advanced at 4.20am. The German garrison had only just arrived, having undertaken a relief just minutes before the attack went in.

German SOS flares went up, which were mistaken for British flares. As a result a considerable bombardment of the trenches took place. The war diary describes how a carrying party (bringing ammunition and bombs up to the newly captured trenches) was hit by German machine gun fire saying ‘five of the carrying party were wounded at this point’. During the consolidation considerable sniping activity took place the diary stating ‘it was at this juncture that most of our casualties occurred. ’

The comprehensive account concludes with the statement that “The total casualties incurred…. Were 5 killed, 31 wounded and 1 missing”.[6]

Into May

Correspondence from William James back home tells us he was still fit and unwounded in early May and concerned about William George being called into the army, despite his age….

8/5/18

Dear Dad,

I have waited for a letter from you before writing but nothing has turned up, the mail is very irregular it seems as only about 5 per cent of my letters to England have ever been delivered. At present I am attached to the New Zealand Engineers on trenching and trench pioneer work so letters had better be addressed as “attached N.Z.E.T.C, B.E.F.. We are not actually in the front line now, though our work takes us into the support line under fire, it is quite a good start and I hope it will last.

What is happening with regard to the calling up of the 50-56 class? I hope most fervently that it will not affect you, but if it does, don’t, unless forced, join the infantry, try the Navy, the air services or in fact anything else…

Cheerio Dad,

Boy

Shortly after the above letter was written he was wounded, and a week later wrote home, as seen on the following letter

15/5/18

Dear Dad,

It is rather long since I wrote to you but it can’t be helped. You see, I unfortunately “caught up” on Fritz’s wire one night when paying him a visit and wire that hasn’t been cleared for a few years can be quite unpleasant. In this case however it only ???? my right hand slightly but I have been in hospital for a week or so now, moving gradually down the line finally ending up here, the 7th Canadians General Hospital. It is a very fine place but rather a good target as you may have read in the papers but apart from little things of that sort we might almost forget the war for a while. I expect to be “at it” again soon though, things are looking rather warm too from the papers, and I have left the NZ ETC now, and shall rejoin the Batt. when I leave hospital.

Please thank mother and Doll [probably Dorothy - his sister] for their ideal parcel, nothing could have been more acceptable. I would write a special letter but my hand starts aching if worked too hard. Convey my kind regards to all those desiring them.

Keep cheerful and don’t join the army – yet.

Boy

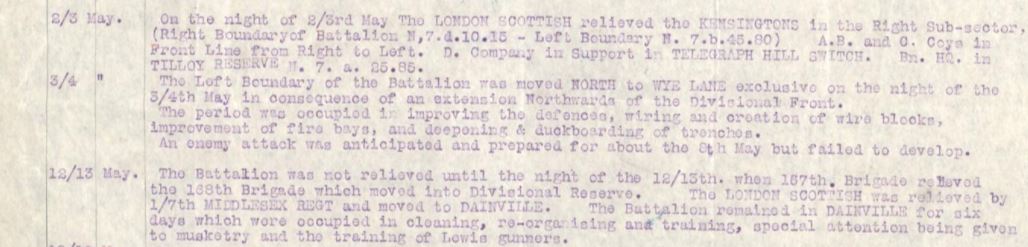

The London Scottish war diary for this period unfortunately gives no details that help us with what happened to him reporting: "the period was occupied in improving the defences, wiring and creation of wire blocks, improvement of fire bays, and deepening and duckboarding of trenches'. Tellingly it also says 'an enemy attack was anticipated and prepared for about the 8th May but failed to develop'.

William James was obviously wounded, probably whilst ‘improving the defences’, and ended up in early June in hospital at Etaples.

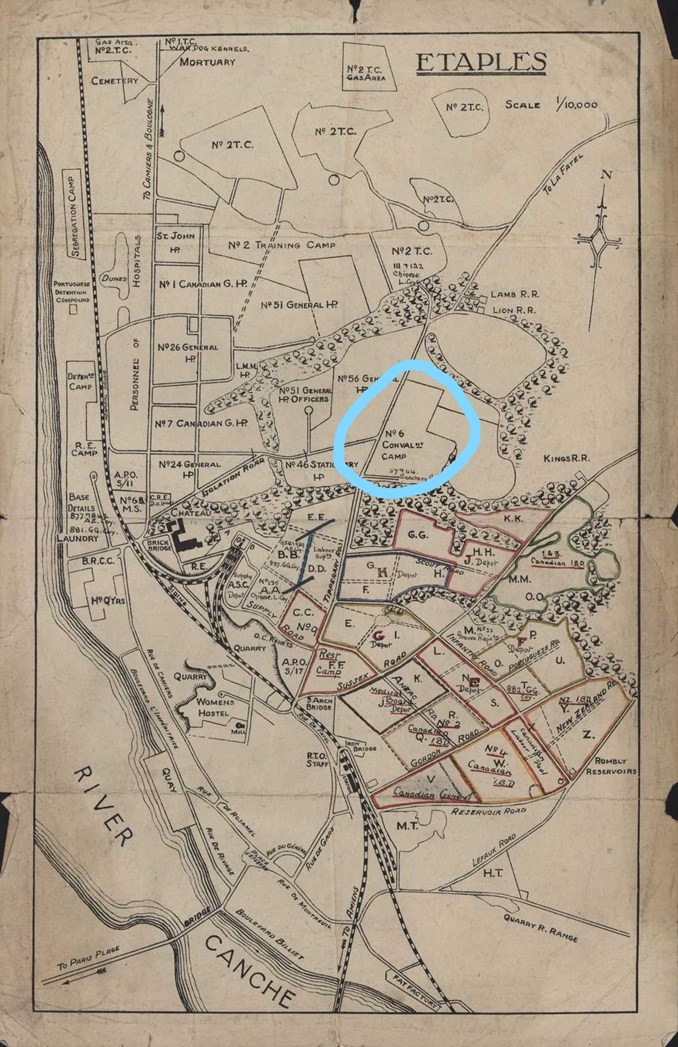

Convalescent Depot Number 6.

Early June we hear he is now out of hospital

6/6/18

Dear Dad,

Since my letter of a few days ago written from No 7 Can. Gen. Hospital I have again changed my address, this time to No 6 Convalescent Depot, Hut 6, ‘B’ Coy situated in the same camp. It is a glorious place this, giving a view out over the sea through pine groves very like Bournemouth. I hope to get some bathing if I stop here any time at Paris-Plage, about 4 kilo’s away on the coast whose gleaming walls seem in the sun like some fairy city – after the line I am very much better in health now and have obtained a post in the Orderly Room which I hope will last for a week or so….

Your

Boy

Casualties who had recovered from their wounds were often transferred to one or other of the various Convalescent Depots after being discharged from a the numerous General or Stationary Hospital at Etaples. Here they would stay for a short period before being moved to a Base Depot and sent back to their units at the front.

Above: British red cross hut, Convalescent depot, Ecaull (US National Archives)

Above: Scene at Convalescent Camp in Etaples, France (US National Archives)

Above: Map of the hospitals around Etaples. Convalescent Camp Number 6 is circled.

His next letter gives us a little information about how he came to be wounded.

27/7/18

Dear people,

……I don’t [know] whether I told you but not long ago I got blown up by a Minnie which landed a few yards away in the next bay up the trench laying me right out for over two hours. Such things are not calculated to improve one’s health you know, when I wrote saying that my hand was ‘bad’ you asked had I been in the front line? Well, the wire that tore my hand & legs was only about 5 feet from fritz’s trench it should have been cut but it wasn’t and when two or three of us fell into the trap. I should th???? He opened fire with every machine gun and rifle in the line “at least it seemed so”. We had to stay there for hours until things quieted down a bit. Yes it was pure excitement, that’s because ‘all’s well that ends well’ but you can guess that this place with its cool green forests and stunning sands seems like heaven.

I will write again soon but time is limited now – hence the scrawl and pencil.

Cheerio,

Boy

Above: An undated photograph of William James seemingly in hospital. He is believed to be on the left of the photo. Courtesy of Naomi Lewis

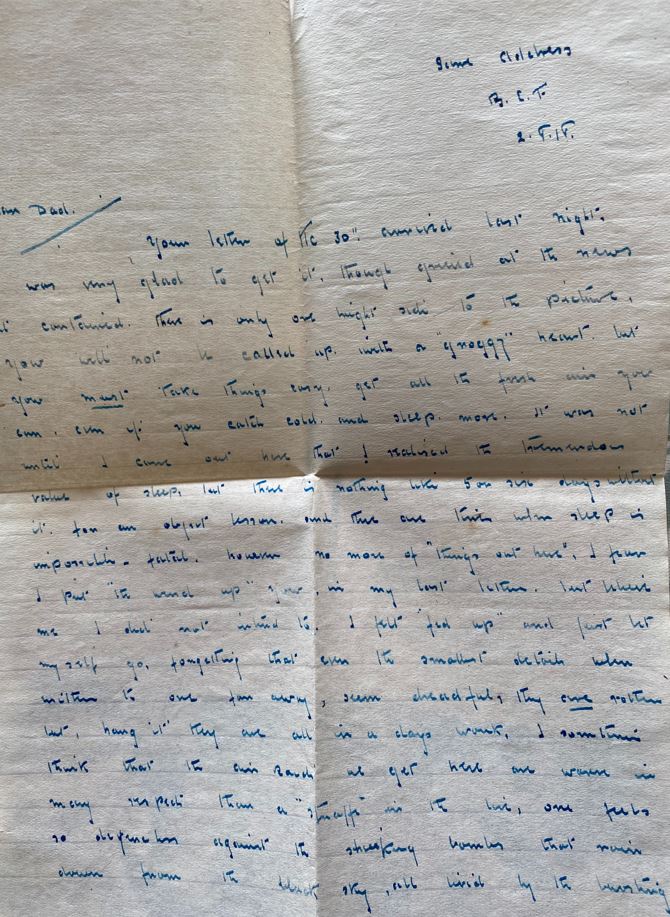

His last surviving letter - dated 2 August - refers to an air raid on Etaples. He also refers again to going swimming in the sea, and there is another reference to the scouting movement.

Same address

B.E.F.

2/8/18

Dear Dad,

Your letter of the 30th arrived last night. I was very glad to get it, though grieved at the news it contained. There is only one bright side to the picture, you will not be called up with a “groggy” heart but you must take things easy, get all the fresh air you can, even if you catch cold, and sleep more...

I sometimes think that the air raids we get here are worse in many respects than a “straffe” in the line, one feels so defenceless against the shrieking bombs that rain down from the black sky, all livid by the bursting of our shrapnel… the dull red glow of burning hospital buildings rises like a ?????? the dead for justice. “He” visited us last night but did not do any harm here.

I went bathing in the sea yesterday, it was ???? to get in the water again.

So you will have to leave the Scouts: it is a great pity for you have done splendid work, but you must rest so let them run alone for a while though I should certainly go to camp with them. It will do you good. Good luck! Many thanks to you both for the writing pad and sketch…

Wishing you any ???? and wealth. Your affectionate son,

Boy

On 4 August a memorial service took place at the ever-expanding cemetery to mark the fourth anniversary of the start of the war. It is possible William James took part in this.

Above: A general view of the procession at the great memorial service held in a British military cemetery in Etaples, France commemorating the fourth anniversary of World War I. A contingent of nurses joins the procession. Soldiers stand in the foreground in front of rows of war graves. Photograph taken 4 August 1918 by Henry Armytage Sanders. (Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand)

It is likely that William James would have been returned to his unit, had he not decided on 12 August to go to the nearby beach with one of his friends.

Paris Plage incident

Activities took place at Paris Plage to keep the recovering wounded amused. These included, for instance, various sports including baseball which was probably quite a novelty for British soldiers.

Above: Convalescent troops at Paris-Plage watching baseball, 18 May 1918. (IWM Q 11499)

It is likely that convalescing soldiers were encouraged (or at least not discouraged) from going swimming at the nearby Paris Plage. An added attraction would have been the opportunity to meet the young ladies in the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps and similar units.

Above: Convalescing soldiers sea-bathing, Etaples. (IWM Q 3527)

The beach is a popular tourist spot to this day.

Above and below: Paris Plage courtesy of Google Street View

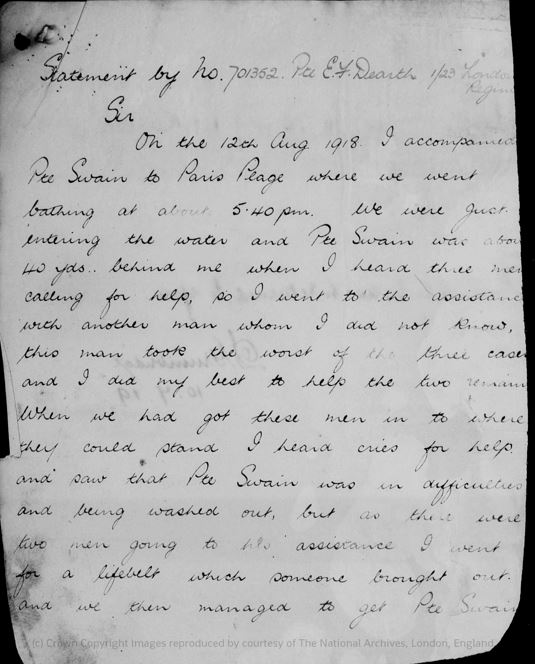

What happened at Paris Plage on 12 August 1918 is detailed in an account that can be found in William James’s service record.

In very neat handwriting, Number 701352 Private EF Dearth of 1/23 London Regiment gave the following statement:

Sir

On the 12th August 1918 I accompanied Pte Swain to Paris Plage where we went bathing at about 5.40pm We were just entering the water and Pte Swain was about 40 yards behind me when I heard three men calling for help, so I went to the assistance [of them] with another man who I did not know, this man took the worst of the three cases and I did my best to help the other two remaining.

When we had got these men in to where they could stand I heard cries for help and saw that Pte Swain was in difficulties and being washed out, but as there were two men going to his assistance I went for a lifebelt which someone brought out and we then managed to get Pte Swain into it and then towed him in.

I accompanied Pte Swain from ? to 20 Field Ambulance to No 26 General Hospital.

Etaples 13/8/18.

Pte EF Dearth 701352

1/23 London Regiment.

Private Dearth was – unlike William James – an experienced soldier who had arrived in France as early as October 1915.

Above: The Medal Index Card for Ernest Dearth. He seems to have survived the war.

There is also a form ‘Report on Accidental or Self Inflicted Injuries' which gives us further details. It states that 515203 Pte Swain, Wm de Tolle 1/14 London Regiment was a patient in 6 Con (ie Convalescent) Depot, this goes on to say:

“Died in no 26 General Hospital at 1pm on 13 August 1918 as a result of Oedema of Lungs - Dilated Heart.”[7] A ‘short statement’ additionally tells us “This man was attempting to rescue some soldiers who were in difficulties when he was overcome himself and rendered unconscious.”

As to whether he was on duty or not, the original ‘Not’ was changed to ‘on duty’ and was to be classified as ‘Injuries (accidental)’

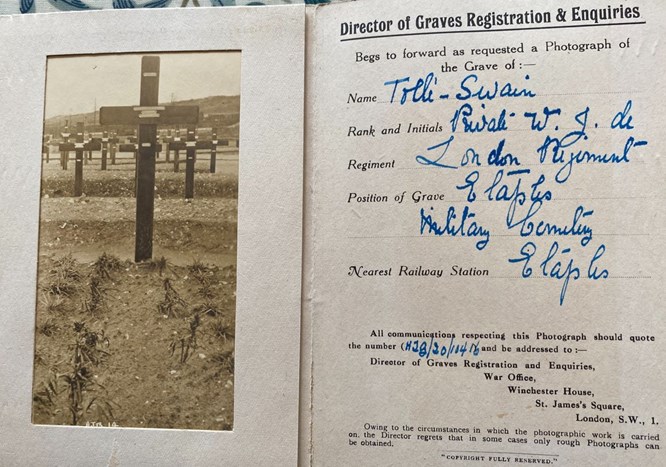

William James de Tolle Swain was buried at Etaples – among the many thousands others who had passed away at the town’s hospitals.

Above: Etaples Military Cemetery in the snow 1919

Above: A photograph of the original grave marker as sent to the family. Courtesy of Naomi Lewis

Personal Effects and Letters destroyed

Within the file is a note saying that William James’s letters should not be returned to his family as his father has asked that they be destroyed. Although unusual and not necessarily suspicious, in view of previous activities, the possible contents of the letters and reasons for the request for them to be destroyed is intriguing.

Above: From William James's service file is a document which tells us his letters should not be returned to his family, but destroyed.

There is also a letter from William George – written on the headed paper of his scout unit which complains about the non-return of various personal effects. The letter is dated 22 November 1918.

Dear Sir

I ??? acknowledge on enclosed form the receipt of the articles as per list. There are several other things which should have come to hand- ??? fountain pen which he was using up to the last letter he wrote home – leather writing case measuring 10” x 12” containing MSS & photos also 3 War Savings cards & certificates. I should be glad if you could ???????? one can understand ??????? killed in the firing line ????????? hospital where the ??????? personally. I of course quite recognise that your office in London is not in any way to blame but unfortunately the same kind of thing has occurred & practically every case has ???? to many unpleasant suggestions as to RAMC orderlies & friends not saying very much about it at the time simply from patriotic motives while the war has still to be carried on but it is certainly one of those things the boys themselves will have explained when they get home. I am writing of what I know as 50 members of my Scout Troop are on active service and I keep in touch with them all.

Yours faithfully

De Tolle- Swain

Après la Guerre

It seems the Swains continued running the Scout troop into 1919. William George and Florence being mentioned in the Bournemouth Guardian on 4 January 1919 as being present at an entertainment given by the troop.

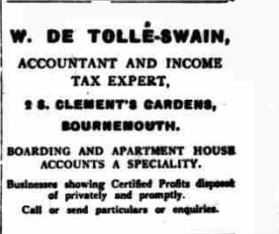

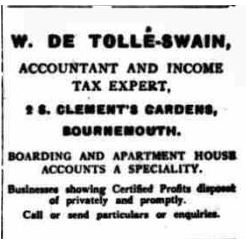

This is the last reference to the family so far found in newspaper reports online. However, during 1921 a series of adverts appeared in the Bournemouth Guardian for William George who had set himself up as an ‘Accountant and Income Tax Expert’.

Above: One of the adverts found in the Bournemouth Guardian - these seem to have all appeared in 1921

At about this time they would have received a communication from the Imperial War Graves Commission in order to provide details – these are what we see today in the CWGC’s registers. This is the point at which William George added the back story to his family by introducing the ‘Comte and Comtesse’ and giving William James the title of Viscomte.

Although it was initially believed this was some ‘scheme’ that William George was running, letters do suggest that he genuinely believed – although totally incorrectly – that the family were descended from French nobility.

To Weymouth

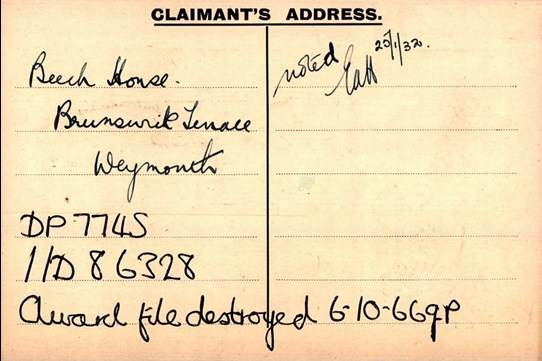

At some stage - presumably in the 1920s - they moved to along the coast to nearby Weymouth. The Pension Record card (below) and also Electoral Rolls tell us that they resided at 22 Brunswick Terrace.

Above and below: One of the Pension Record Cards within the Pension Record and Ledger archive saved by The Western Front Association.

This property is an end of terrace guest house.

Above: 22 Brunswick Terrace Weymouth - now 'The Windsor' Guest House (Google street view)

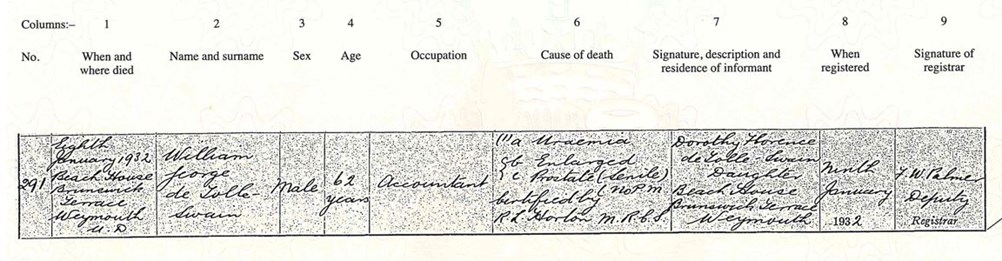

William George died on 8 January 1932 in Weymouth aged 62. He was still calling himself de Tolle, and detailed his occupation as an accountant. But seemed to have dropped the French aristocratic title. The death certificate suggests prostate cancer.[8]

Above: William George de Tolle Swain's death certificate.

Florence outlived him, she can be seen on the 1939 register living with their daughter Dorothy (now Dorothy Lewis) at number 96 Chiltern Road, Reading.

The last of those mentioned in this piece – Dorothy – died in 1970.

Conclusion

It is almost likely that the ‘de Tolle’ extension to the name ‘Swain’ was created by William George in order to hide his previous criminal convictions, but the ‘track covering’ here did not seem particularly thorough. It is even more likely that the ‘Comte and Comtesse’ was another fiction – but only seems to have been evidenced in the Commonwealth War Graves documentation. The details provided by the parents certainly make the headstone one that stands out, and for this reason the story above has been unearthed. Possibly this was the last thing they expected when William George and Florence gave the details to the Imperial (as it was then) War Graves Commission who, obviously, could not be expected to verify the claims made by individuals. It is also notable that the register entry says:

'enlisted at Bournemouth while living there'

The implication being that they were at Bournemouth temporarily which adds to the myth they seemed to be creating about being of a French noble family.

As a result of this false (or at best extremely dubious) information, this has been perpetuated on William James’s headstone for more than 100 years. But ironically, had William George not added this back story, we would not have unearthed the facts around William James’s death.

It is without doubt that William James was acting bravely when he attempted the rescue of the drowning soldiers and that he was ‘used’ by his parents and was too young to be responsible for what went on before the war.

Unfortunately he was not one of those to come home in 1919.

Above: The London Scottish Arriving Back From France In London 16th May 1919 © UK Photo and Social History Archive

Above: The 'death penny' and medals and badges remain in the family

Article by David Tattersfield and Jill Stewart

The authors would like to sincerely thank Naomi Lewis, who is descended from William James's sister Dorothy for her significant assistance with this piece

[1] To date no 1891 Census information has been located relating to William George Swain.

[2] The pretence must be a false pretence of some existing fact, made for the purpose of inducing the prosecutor to part with his property (e.g. it was held not to be a false pretence to promise to pay for goods on delivery), and it may be by either words or conduct. The property, too, must have been actually obtained by the false pretence. The owner must be induced by the pretence to make over the absolute and immediate ownership of the goods, otherwise it is larceny by means of a trick. It is not always easy, however, to draw a distinction between the various classes of offences. In the case where a man goes into a restaurant and orders a meal, and, after consuming it, says that he has no means of paying for it, it was usual to convict for obtaining food by false pretences. But in R v Jones [1898] 1 QB 119, an English court found that it is neither larceny nor false pretences, but an offence under the Debtors Act 1869, of obtaining credit by fraud. [Wikipedia]

[3] The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 140 Home Office: Calendar of Prisoners; Reference: HO 140/308

[4] England & Wales, Crime, Prisons & Punishment, 1770-1935 Accessed via Find My Past

[5] The National Registration Act 1915 provided for a register of all persons between the ages of 15 and 65, who were not members of the Armed Forces. The central registration authority was the Registrar General acting under the direction of the Local Government Board, while the councils of metropolitan and municipal boroughs and all urban and rural districts were the local registration authorities. The information supplied under the Act provided manpower statistics and also enabled the military authorities to discriminate between persons who should be called up for military service and those who should in the national interest be retained in civil employment. [The National Archives]

[6] CWGC tells us six men from the battalion were killed on this day. All but one have no known grave and are commemorated on the Arras Memorial. The known grave is at Dainville British Cemetery.

[7] Dr Peter Hodgkinson tells us: “The lung oedema would be the drowning autopsy finding. The dilated heart would not be a drowning finding - it would have been the cause of him getting into trouble in the water - he would have become short of breath and fatigued easily."

[8] Our thanks to Peter Hodgkinson again for this.