The First Non-Stop Transatlantic Flight by Alcock and Brown in 1919

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The First Non-Stop Transatlantic Flight by Alcock and Brown in 1919

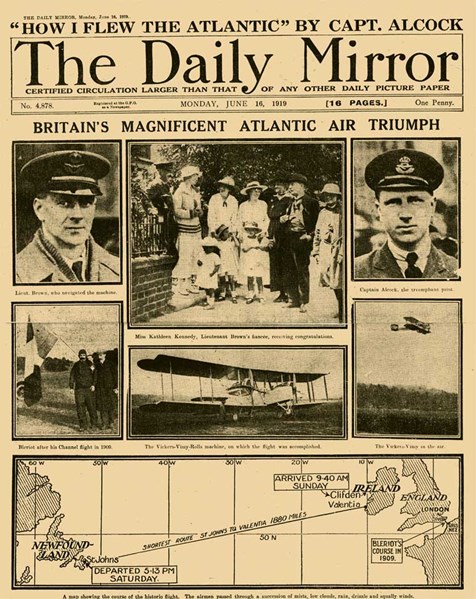

In 1913, the Daily Mail newspaper offered a prize of £10,000 to ‘the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight from any point in the United States of America, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours’.

The competition was suspended with the outbreak of war in August 1914 but two aviators, Captain John Alcock DSO and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown, had dreams of flying the Atlantic. Both had been prisoners of war during the conflict, Alcock in Turkey and Brown in Germany.

Above: John Alcock and Arthur Brown

By May 1919, several teams had thrown their hats into the ring, with Brown and Alcock of the Vickers Team regarded as outsiders. Indeed, when they arrived in Newfoundland in May 1919, they were met with the news that British airmen, Hawker and Grieve, had already taken off. That flight ended with the pair missing for almost a week after they were forced to ditch into the sea – they were subsequently rescued by a Danish trawler.

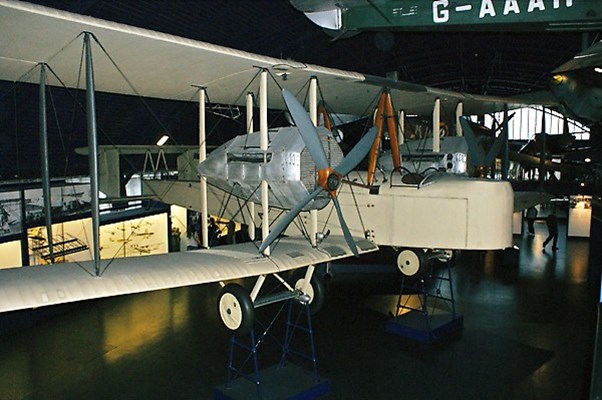

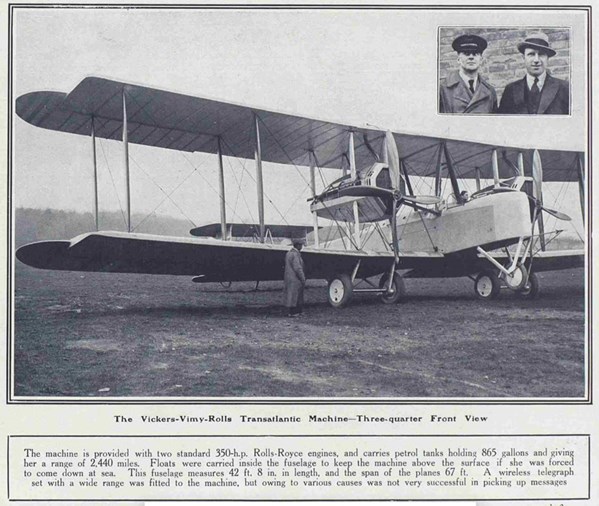

The aircraft in which they would make their epic flight was a modified Vimy IV twin engine.

Above: Alcock and Brown’s Vimy plane. Photo – Science Museum

At around 1.45pm on 14 June, the pair took off.

Above: Alcock and Brown before take off

Above: the take off - Photo – Canadian Archives

The flight was not easy – equipment failures deprived them of radio contact, their intercom and heating. Bad weather also added to their difficulties with a thick fog encountered a few hours into the flight. This prevented Brown from being able to navigate using his sextant and having to rely solely on dead reckoning. Just after midnight, they did get a glimpse of stars and found that they were on course.

In the middle of the night of 15 June, they flew into a large snowstorm which drenched them and iced up instruments.

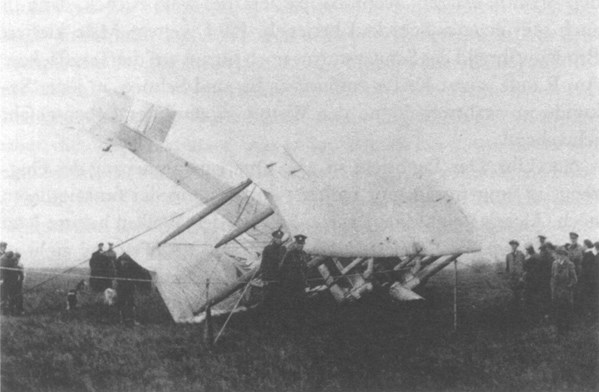

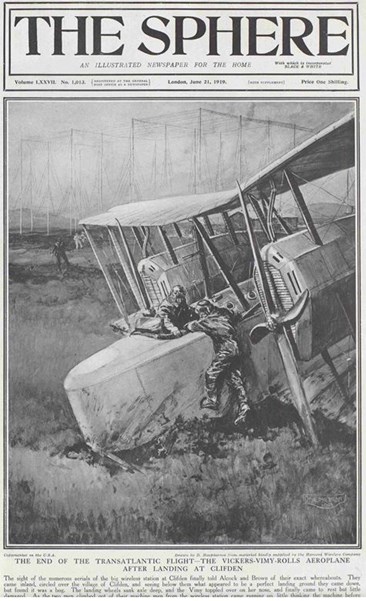

Finally, just after 8am on 15 June, they saw specks of green, small islands off the coast of Ireland. Within a few minutes they identified a potential landing area, but what looked like a meadow was in fact a bog, and on landing, the plane sank axle deep and turned over on its nose, although neither man was hurt.

Above: the Vimy landed at Clifden, County Galway

Above: The Sphere’s picture of the Vimy’s landing

Afterwards, they said that they had only once felt they were in any danger during the flight, when Alcock found himself driving straight towards the surface of the ocean and when not more that 10 feet from the water he snatched the machine so rapidly that it almost looped the loop. However, Alcock is also reported to have said ‘We have had a terrible journey. The wonder is that we are here at all…’.

Above: the headlines from the Daily Mirror

Above: pictures of the plane – The Sphere

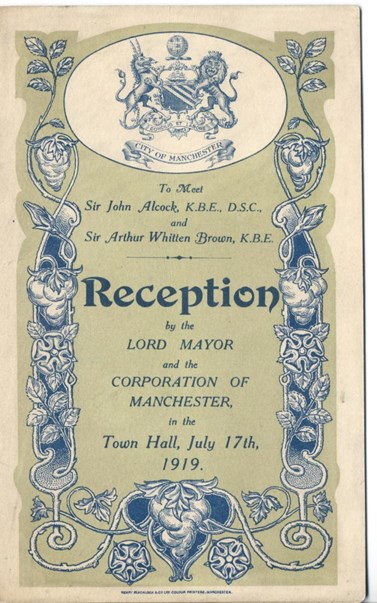

Alcock and Brown were treated as heroes as news of their achievement became known. Crowds gathered at all the railway stations through which they would later travel on their return to England. They were presented with their £10,000 prize by Winston Churchill and both were knighted a few days later by King George V.

Above: A civic reception was held for them in Manchester.

The flight also marked the first transatlantic air mail as the pair had carried letters from America with them.

Sadly, Sir John Alcock would not live long after his transatlantic flight. In December 1919 he was killed whilst flying to an aircraft exhibition in Paris, when his plane crashed near Rouen in thick fog. Brown was devastated by Alcock’s death and reportedly, never flew again. After the loss of his son whilst serving in the RAF during the Second World War, he became a recluse and died at the age of 62 in 1948.

Over the years, a number of memorials were erected in Newfoundland and County Galway.

Above: one of the memorials near the landing site.

Above: The cairn erected at the landing site in County Galway

Above: The sculpture of Alcock and Brown which for many years was located at Heathrow Airport before being relocated to Clifden, County Galway.

Article by Jill Stewart, Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association