The First Tanks at Elveden by David Fletcher

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The First Tanks at Elveden by David Fletcher

Drive up the A11, through Suffolk, as if you are heading for Thetford in Norfolk and if you can take your eyes off the road for a moment you will see the massive US Air Force base at Mildenhall, on the left. Then, you will see, sticking up above the trees, the tall War Memorial, commissioned by Lord Iveagh to commemorate those from the three adjacent parishes who lost their lives in the First World War. Now you are in the presence of history, for that land, off to your right, is Elveden Estate, the first ever tank training ground, established even before anyone had ever heard of Bovington.

Not that there is anything now to see there - nothing tank related anyway: the trenches are all gone, along with the artificial shell holes and barbed wire as is the special railway siding. That was all cleared away and tidied up when the tanks left.

|

| Tank No. 713, another male, built by the Oldbury Railway Wagon and Carriage Company seen here at Elveden running without sponsons. |

The story of how Elveden came to be found, the negotiations with Lord Iveagh and its brief period of use have been told very well in Major, as he was then, E D Swinton’s book 'Eyewitness'. Since then other people have chipped in with their recollections or views so that now the 'tale has become a little garbled and a certain amount of mythology has crept in. Here the widely respected and acclaimed historian of tank warfare David Fletcher of the Tank Museum sorts fact from fiction.

|

| Ernest Dunlop Swinton, Royal Engineers, in later life. |

Conception of the 'Mother' tank had its problems

Luck had a large part to play in the selection of Elveden as the first tank training ground. Swinton discovered a Major O C Tandy, Royal Engineers who had worked for the Survey of India. Tandy was at home, recovering from wounds and working for the War Office on light duties. Swinton was able to borrow him and after some searching, it was Tand who discovered the site at Elveden, known in those days as the Land of the ‘Big Shoots’ where the Great and the Good, from the King downwards, went to kill the game birds in season. Swinton went and inspected the site. He described it as about fifteen square miles of land, mostly sandy soil with vast areas of arable, heathland, rides, screens and trees; altogether ideal for tank training with a limited number of tanks. He and Tandy then called upon Drivers Jonas at the War Office Land Branch who arranged to evict the inhabitants and turn the land over to the army. This was in April 1916 and by the end of the month, the land was theirs. Swinton felt he ought to tell Lord Iveagh, who owned the estate, what was afoot. He telephoned, but Lord Iveagh was not best pleased with the thought of his pride and joy being turned over to some mysterious military purpose. However, by taking the line that if it wasn’t him, it would be one of his neighbours Lord Iveagh loyally agreed to cooperate.

The Heavy Section, Machine Gun Corps, as it was known in those days, had already started recruiting men and had set itself up at Bisley in Surrey but had nowhere to play with its tanks. That is why it needed Elveden. The first tank to arrive was Mother, the prototype of all tanks, which came by rail from Lincoln on 4 June 1916. It arrived at Barnham station of the Great Eastern Railway, on the single track line between Bury St Edmunds and Thetford, now long gone. Mother is said to have been unloaded and driven by road to Elveden. This had to be done after dark and residents were warned to keep their blinds and curtains drawn and not to peek out of the window as it crawled by. According to legend,, the tank was without its two six-pounder guns which had been retained for instructional purposes at Bisley, although it was still fitted with empty male sponsons. . On the face of it this seems to be a bit ridiculous since the sponsons would have to be taken off so that the tank could travel by rail, so refitting them at Barnham station would seem to be a rather pointless exercise.

But that brings us to another point. According to The Tank Corps by Major Clough Williams-Ellis, the first tanks to arrive at Thetford (everybody called it Thetford in those days) included some that were not armoured but built from boilerplate and intended only for training. [1] You’ll find the same thing on p.35 of Vol. 12 of The History of the Ministry of Munitions, which was written some years later. Now it would make a lot of sense to build some unarmoured prototypes, but we have no other evidence for this at all. According to all the other sources 150 tanks were built, 75 male and 75 female to be distributed, 25 each, to six tank companies for use in action, so they all would need to be armoured, and six times 25 comes to 150, at least it did when I was at school! There is no further evidence anywhere of even a few unarmoured training tanks being built and such photographs of tanks that we have from Elveden are all from this batch of 150.

The development of the tank was top secret

The first batch of production tanks arrived at Barnham station on 18 June 1916, followed by others, and twenty are said to have been delivered on 10 July. They would have come from Fosters of Lincoln or The Oldbury Railway Carriage and Wagon works near Birmingham and would all have been without their sponsons which were not ready. So at first men were taught to drive in tanks that did not have sponsons. This was criticised by Second Lieutenant P H Johnson of the Army Service Corps (ASC). He regarded it as unrealistic, particularly since the tanks were lighter than they would otherwise be. Johnson claimed that without sponsons the tanks were 8 tons lighter than they should have been. He was wrong on that score since two sponsons, complete with guns and ammunition only weighed about 4 tons and the real problem only manifested itself when the sponsons did arrive, it was found that in the meantime tanks that had been run without sponsons had twisted to such an extent that the bolt holes would no longer line up with those on the sponsons, so new ones had to be drilled before they could be fitted.

|

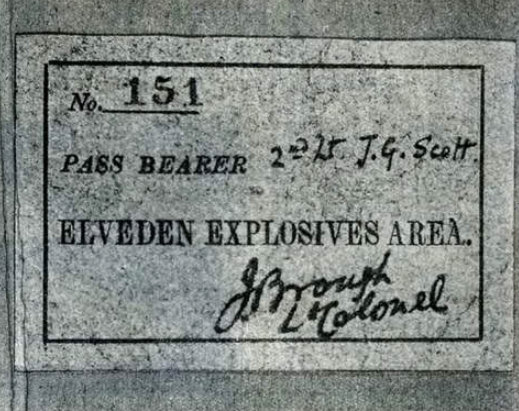

The site at Elveden itself was regarded as ‘Top Secret’, and screens were erected alongside the main road, what is now the A 11, to hide what was going on. The site was known as the Elveden Explosives Area and loud explosions helped to confirm this in the minds of the adjacent population. A special pass was required to gain entry. The entire site was patrolled, day and night, by men from the Royal Defence Corps and Cavalry, who had no idea what they were guarding. Inside, the very centre of the site where tank training was done was known as ‘The Area’, this was also cordoned off and patrolled as was the adjacent ‘Training Area’ which was where all manner of training that did not actually involve tanks, was undertaken. The Brandon Road - the present day B 1100 - cut clean across the secret area so this was closed at both ends and the site also included part of the adjacent estates belonging to Lord Cadogan and the elderly Duke of Grafton.

|

|

| A special pass permitting someone to enter the Elveden Explosives Area signed by Lieutenant Colonel J Brough of the Royal Marine Artillery, who was elected to command the tanks in France. |

Early in July 1916 the Great Eastern Railway constructed a double track siding off the main line which led straight onto the site. Tanks could now be unloaded, after dark, without having to make the road journey from Barnham station. Swinton implies that the siding was opened before the first tanks arrived, as does Sergeant Dawson in his recollections but both are wrong, if you judge by official documents relating to the work. The site of the siding was near Culford Lodge Farm (simply Lodge Farm in those days) but there is not a trace of it on the ground now.

The ASC provided drivers for the tanks, many of them from the Caterpillar Depot at Avonmouth Docks, where they were supposed to have some experience of tracked vehicles, but also from the ASC Depot at Grove Park in London and even from Holt Tractor Companies in France. They were commanded initially by Major Hugh Knothe, who had also served with the Caterpillars in France, until, in the fullness of time Knothe was sent over to France with a team of ASC engineers in advance of the tanks and command of the men at Elveden devolved upon Captain H P G Steedman. The ASC men were formed into 711 Company, but some of them were so overawed by the tanks that they claimed to have no knowledge of internal combustion engines at all, as a result these men were returned to their units but even so, to their credit, kept quiet about what they had seen.

A Royal Academician developed camouflage for the first tanks

Swinton also borrowed the society portrait artist and Royal Academician Solomon J Solomon, then a Lieutenant Colonel of Royal Engineers - who had already visited General Herbert Plumer on the Western Front to advise on camouflage techniques - to devise a suitable camouflage scheme for the tanks. Swinton says that Solomon came in May and brought with him tons of paint. He set up his studio in one of the barns and painted the tanks as they arrived. Swinton also says that he turned up every day on a pony.

|

| The barn at Bernersfield Farm where Solomon J Solomon is believed to have done his painting. |

Basil Henriques, who commanded tank C22, says that he and his crew were ordered to paint their tank in the style devised by Solomon, using a tank the artist had painted as an example. If this was true of all crews then the odds are that Solomon only ever painted one tank, probably Mother. John Glanfield claims that the scheme devised by Solomon looked more suited to sunset in Sherwood Forest than to the muddy conditions on the Western Front, while Basil Henriques says that when he arrived in France he and his crew were ordered to repaint C22 in patches of duller colours, outlined in black.

|

| As close as we can get to Solomon’s camouflage, from the painting ‘A Tank in Action’ by John Hassall RA. |

|

| A photograph taken at Elveden of a female tank in Solomon’s camouflage; it is believed to be 508, Second Lieutenant L V Smith’s C18 Casa and it has been suggested that the wire mesh on top is some sort of wireless aerial. |

A number of ideas were investigated, mostly by Swinton, in connection with tank communication and navigation. The first of these involved a wireless set. This was devised by the Royal Engineers Experimental Wireless Establishment at Worcester. They came up with a compact set working on a wavelength of 200 metres, with a range of about three miles but this was rejected by GHQ in France on the grounds that it might interfere with other transmissions. Another idea was to provide section leaders’ tanks with a telephone handset and 1,000 yards of cable on a reel attached to the tail, which would be unwound as the tank went along. However after 1,000 yards the cable ran out and the handset was useless so that idea was dropped too. Tanks could still signal to one another using flags or discs of metal on sticks but there was always a risk of these being shot away in action, assuming the crew could find them amongst all the other stuff dumped on the floor of a tank when it went into action! Another of Swinton’s ideas was to fly a line of miniature barrage balloons that the tanks could aim for when coming out of action, while coloured balloons could be hoisted up the cable to send simple signals to the tanks, but GHQ did not like the idea of the miniature barrage balloons either so that idea had to be dropped.

To Test the first tanks there was a mock battle

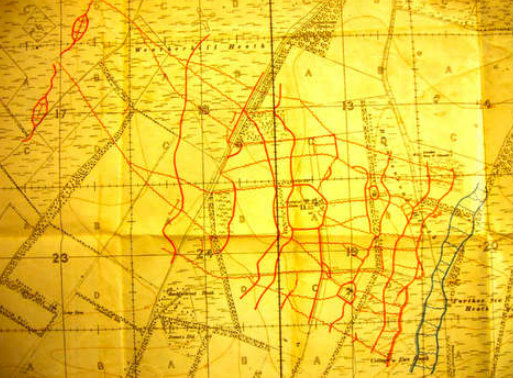

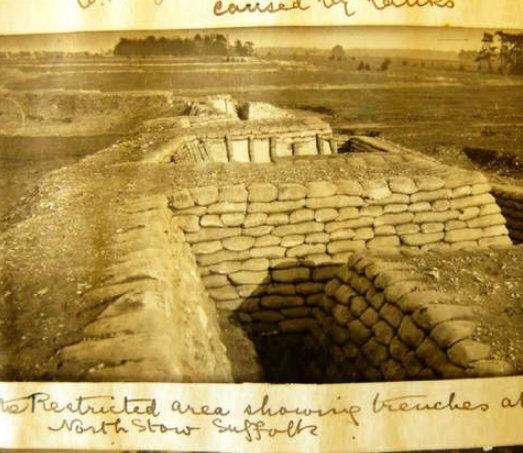

Swinton also wished to include a replica trench system for the tanks to practice over. He had to indent for one million sandbags and miles of barbed wire to finish the trenches off. This resulted in the arrival from France of Captain Giffard le Q Martel, a Royal Engineers officer with particular knowledge of British and German trenches, Martel was destined to serve with the Tank Corps for the rest of the war but for the moment he was given command of the Home Defence Corps Pioneers and tasked with completing the trenches, the barbed wire and shell holes required on the practice battlefield. Swinton says it was ‘as complete a copy of the real thing as time, experience, labour and money could make it’ while the ‘German’ trenches were even provided with signs in German and the men taught to understand what they meant. On 21 July a mock battle was arranged over these trenches before an invited audience of senior officers and the Minister of Munitions, David Lloyd-George. Twenty five tanks took part, advancing from behind the audience, gathered on a raised platform of turf, moving westwards towards North Stow Farm (now North Stow Hall) but then known as ‘The Citadel’ since it was the centre of enemy defence. The attack was apparently most successful and was photographed from the air by pilots of the Royal Flying Corps from an airfield near Thetford. These photographs were processed and rushed to Elveden in time for Swinton to circulate some of them on the train back to London. Unfortunately no trace of these historic photographs has ever been found. Five days later a smaller show was staged over the same ground for His Majesty King George V.

|

| A map showing the entire training and test trench system around North Stow Farm. The blue lines on the right represent the British front line. The ‘German’ defences are in red. |

|

| Sandbags and trenches near North Stow Farm looking better than they ever did in France. |

On 13 August 1916 the first tanks were moved to France

The time was drawing near when the first tanks would be needed in France, but many of them were so worn out that they needed some restoration. Since this was beyond the scope of the ASC Workshops Personnel some forty fitters were acquired from the factory in Birmingham. They were billeted in the area and fed by the Great Eastern Railway, from a restaurant car parked on the siding for the purpose.

The movement of tanks to France began on 13 August 1916. Thirteen tanks from C Company - Major Allen Holford-Walker of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders commanding – were loaded onto a train on the new siding. This operation took two nights, it could only be done at night; a second train followed, loaded with the tanks’ sponsons, spare guns and other stores and then, on the nights of 24/25 August another train was loaded with the remaining twelve tanks of the company plus two spares. Their route took them to Avonmouth Docks on the Bristol Channel where they were loaded aboard ships and, after waiting two days for clearance, sailed for France, the names of the ships they sailed on are not recorded. They arrived at Le Havre, the first batch of men (from Southampton) on the 17th, their tanks on the 21st. They were sent by rail to the training ground at Yvrench, near Abbeville. The second batch of tanks arrived at Le Havre on 25 August although the men, again sailing from Southampton, preceded their tanks by a couple of days. They then followed to Yvrench.

There are rumours of tanks being used in battle before 15 September 1916. No evidence for this has ever been found, but it could allude to mock battles fought over the Yvrench training area. The first of these took place on 26 August and involved five tanks of C Company and the 7th Battalion the Middlesex Regiment. This attack was viewed in the afternoon by General Haig (as he was then). Then again, starting on 1 September groups of tanks were in action with infantry brigades from the 56th Division and from then on tanks from both companies were involved.

The travels of D Company, commanded by Major Frank Summers of the Royal Naval Air Service, are far better recorded. Their first train of thirteen tanks left Elveden on 26 August and were loaded aboard the SS Ilston Grange at Avonmouth along with an officer, Lieutenant W J Wakeley and some ASC men to take care of the tanks. It was followed by a second train carrying all the sponsons, spare guns and stores a day later. The second tank train, again carrying fourteen tanks, left on 1 September and they were shipped on board the SS Hunsgate with Second Lieutenant W H Sampson in charge. The men were taken in case a tank broke loose on the voyage and needed moving. Meanwhile the officers and men of D Company (1 and 2 Sections) marched to Thetford Bridge Station on 28 August and caught a train to Liverpool Street from where they marched across London to Waterloo and boarded another train for Southampton. They crossed the Channel on the troopship Caesarea, followed the next day by the men of Nos. 3 and 4 Sections on 2 September. D Company was complete at Yvrench on 6 September and with C Company was now prepared for its date with destiny, 15 September 1916.

|

| The officers of D Company, Heavy Section, The Machine Gun Corps, photographed at Elveden. |

|

| Tank No. 742. A male Mark I built by Fosters in Lincoln, seen running without sponsons at Elveden. It would be the D Company tank D7, commanded by Lieutenant A J Enoch at Flers in September 1916. |

Ten spare tanks, also one assumes, from Elveden were shipped across the Channel and arrived on 10 September. They were followed by A Company (Major C M Tippets, South Wales Borderers) but it arrived in France too late to take part in the first action, while B Company (Major T R McLellan, The Cameronians) went across in October but with no tanks of its own. By this time it is calculated that there were ninety-one tanks in France, including the ten sent as spares. Elveden was very run down, it's useful days were over.

Bovington Camp in Dorset was opened for tanks on 27 October 1916 but the tanks had all been returned to Lincoln for refurbishment. Even when they arrived, eight were removed for shipment to Egypt, the ‘Gaza Detachment’ from E Battalion as it now was, commanded by Major Norman Nutt, Royal Naval Air Service. More tanks would arrive in due course and Bovington would thrive, although that is another story. For the time being, however, it was a big camp with few tanks, more immediately concerned with the expansion of the Heavy Branch, as it had now become, into a substantial force which, within a year, would be known as The Tank Corps.

Article by David Fletcher

This article first appeared in The Western Front Association magazine 'Stand To!' which is only available to WFA members.

Notes:

[1] Country Life, 1919, p.18