The First World War paid off?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The First World War paid off?

[This article was originally published in 'Stand To!' number 104 in September 2015. Members of The Western Front Association can access all back-issues of Stand To! via the 'members' area' of the website. ]

It is appropriate to re-publish this article as the Covid-19 pandemic is causing questions to be asked about the level of national debt, which is comparable to the situation during and immediately after the First World War.

"This is a moment for Britain to be proud of. We can, at last, pay off the debts Britain incurred to fight the First World War. It’s also another fitting way to remember that extraordinary sacrifice of the past."

The above statement, from Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, on 3 December 2014 went on to explain that the UK gilt (Government issued bond) known as 31⁄2% War Loan would be repaid on 9 March 2015. It was the second announcement within weeks relating to the repayment of loans raised by the British Government during the First World War. At the end of October 2014 it had been announced that redemption of £218 million of 4% Consols would take place on 1 February 2015.

Of the two classes of gilt which can be directly attributed to money raised during the First World War, the Consols account for just 10% of the total still 'on the books', and the 31⁄2% War Loan - which currently stands at £1.9 billion (£1,900 million) - accounts for 90%. Interest on these two gilts continue to cost the nation over £75 million every year.

Issued in 1927, the Consols were used to refinance British government bonds that were sold (and bought by the public) during the war years to help fund World War One. These war-time issued bonds were just one part of the UK Government's efforts at financing the war.

The repayment of the 4% Consols is obviously a small matter compared to the repayment of the 31⁄2% War Loan. It is, however, the first time this type of gilt has been redeemed since the late 1940s - in part because until recently the Consols required lower interest payments than similar new debt.

With interest rates being exceptionally low, it seems that the Government is doing some tidying up of its borrowing as well as taking advantage of the ultra-low interest rate environment that we are currently experiencing. Another major part of the raising of money was the issuing of "War Loans".

Do these announcements mean that the costs of the First World War are now "repaid"? Unsurprisingly, the answer to this is complicated. This article will explain the chronology of the War Loans and Bonds issued during the period 1914 - 1918 and also consider the accuracy of the statement made by the Chancellor.

The outbreak of the war, the banks and the finance markets

London was, on the outbreak of the First World War, the premier city in the world in terms of finance; Britain was the world’s economic superpower. With rapid growth and a vast empire, the country enjoyed significant levels of wealth and resources. However, it wasn’t ready for the economic impact war would have.

Ready for War? Henley regatta, 1914. (Bridgeman Art Library)

The week beginning Monday 27 July saw the breakdown of the City’s foreign exchange and discount markets, and culminated in the closure of the London Stock Exchange on Friday 31 July. It stayed shut for five months.

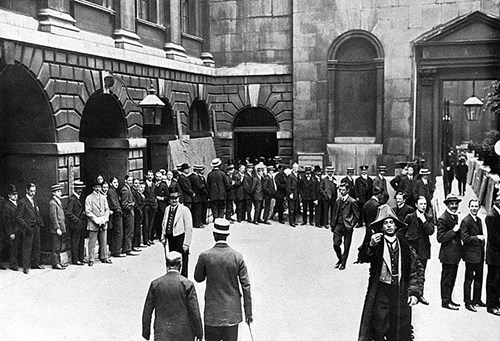

Queues built up at the Bank of England, as investors attempted to change their paper money for gold [1]:

Above: People queue at the Bank of England in July 1914, to change notes into gold

High Street banks rushed to convert their bonds and bills of exchange (a form of IOU used at the time) into cash or use them as collateral for loans from the Bank of England.

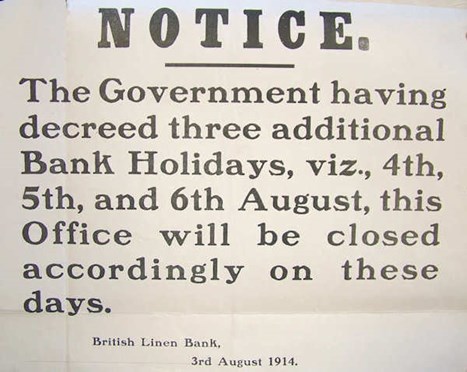

Friday 31 July must have come as a relief for the beleaguered banks. The scheduled August Bank Holiday meant that they were not due to open their doors again until Tuesday morning, however the mounting crisis over that weekend resulted in an extended Bank Holiday being declared, the first "extra" day of this holiday (Tuesday 4 August) seeing the declaration of war at 11pm London time.

Above: Notice of Bank Holiday, British Linen Bank (Courtesy of Lloyds Banking Group)

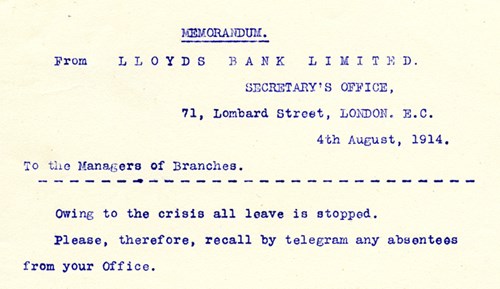

Above: Bank staff leave cancelled! (Courtesy of Lloyds Banking Group)

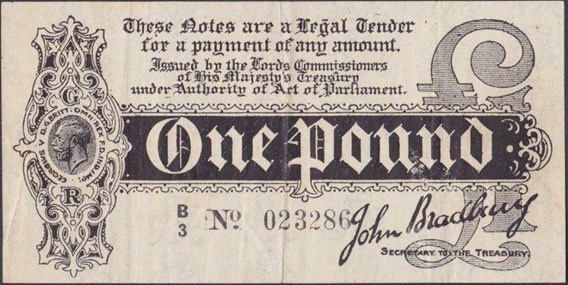

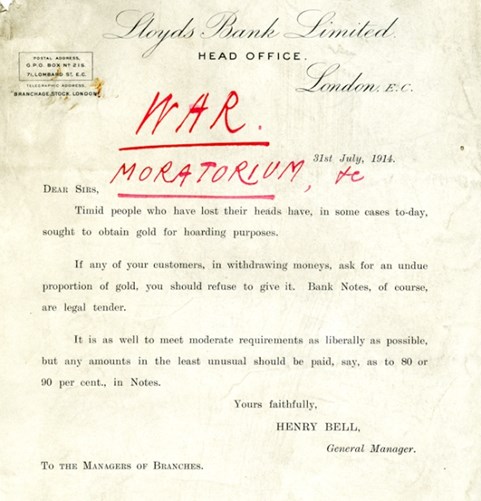

During these extra three days holiday, David Lloyd George (the Chancellor of the Exchequer) had an Act of Parliament drawn up and passed (the Currency and Bank Notes Act), by which Britain left the gold standard. Under this Act the Treasury issued £300 million (equivalent to more than £30 billion today) of paper banknotes (in denominations of £1 and 10 shillings), without the backing of gold. The introduction of hastily printed small denomination currency notes (nicknamed 'Bradburys') issued by the Treasury (not the Bank of England) and the Government passing a “general moratorium” on contracted payments (which allowed banks to refuse to pay out deposits) were designed to prevent a run on the banks when they reopened.

Above: The Treasury rushed out notes signed by Sir John Bradbury, Permanent Secretary to the Treasury. They were nicknamed "Bradburys". This example of an early 1914 note was replaced with more elegantly designed versions a couple of months later.

By withdrawing gold from internal circulation, this Act effectively suspended the gold standard and in practice allowed for an inflationary expansion of the money supply enabling the Government to print notes to cover its obligations. Consequently, the Act gave the Government, operating through the Bank of England, great latitude to issue bank notes beyond the limit authorised by law.

Above: Letter to branch managers, Lloyds Bank, 31 July 1914. (Courtesy of Lloyds Banking Group)

Appeals to patriotism urging citizens not to redeem paper money for gold were successful. When the banks reopened on Friday 7 August, the first Bradburys were printed and ready and there was no run on the banks.

Other measures were put in place. Fearing a financial crisis, the Bank of England opened up every tap to allow liquidity to spread around the City. It bought up financial assets held by banks which had plunged in value because of fears of default by institutions in Europe. In addition, at the end of July, interest rates increased from 3 per cent to 10 per cent (they were reduced back to 5 per cent in early August).

The First War Loan

The Government soon realised the war was going to be very expensive, and that measures would have to be taken to raise money to pay for the munitions that were required. In the first weeks of the war, the government funded its war spending through advances from the Bank of England, but by late autumn 1914 it needed new funds.

On the 7th November the Chancellor of the Exchequer (Lloyd George) presented to the House of Commons the first War Budget, which showed a deficit of £339 million on the assumption that the War would last until the end of March 1915. It is against this background that plans were put in place for what would become the first in a series of war loans.

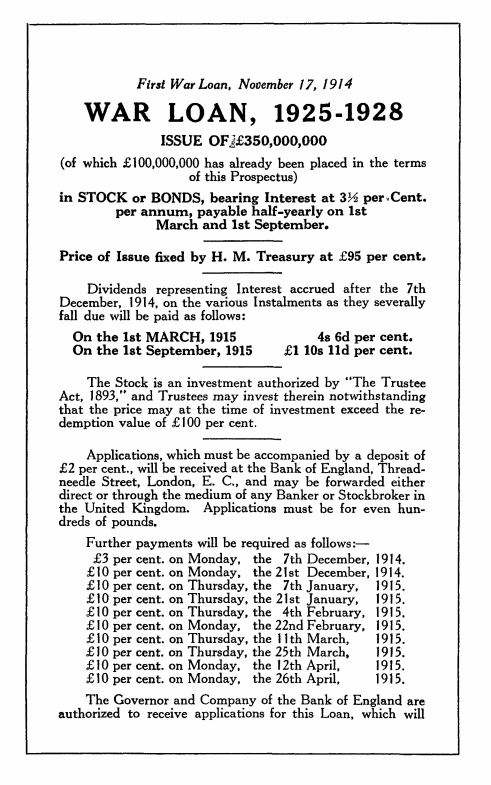

The loan was to be on a scale far larger than any previous government bond, offering £350m of stock (equivalent of £35 billion today). The loan would be six times larger than the previous largest loan obtained (this was £60 million, raised in 1901 to finance the Boer War). The loan would pay interest at a rate of 3.5% and was to be repayable by the Government between 1925 and 1928. This First War Loan was issued at a 5% discount, meaning that investors could buy £100 of stock for just £95 - therefore they could expect an annual return of just over 4% for the expected lifetime of the loan - an attractive return for a government-backed investment.

The First War Loan was aimed at wealthy people and institutions, who could afford the minimum subscription of £100 (equivalent to over £10,000 today). The support of Britain's commercial banks would be important in reaching these potential investors.

Although the issuing of Government debt was a well established procedure for the Bank of England who handled this, the scale of what was being attempted caused real anxieties in terms of how the amount of work would be managed, especially at a time when Bank of England staff were leaving their desks to join the army.

Matters were not helped by the Government offering the purchase of these in ten instalments (over a period of five months) after an initial deposit of £2. Nervous that the loan would not be fully subscribed (and such a failure could be interpreted as a lack of confidence in the handling of the war), the Government applied pressure on the high street banks to not only subscribe to the loan, but also to underwrite the issue ( i.e. take up any unsubscribed stock). A meeting was held at the London County & Westminster Bank on 16 November 1914 between Lloyd George and representatives of the major UK banks. The bankers agreed to Lloyd George's request and nearly all the British banks subscribed 5% of their deposits to the loan, and underwrote the same amount again. They also agreed to encourage customers to invest in the issue.

The High Street banks' agreement in taking the stock enabled just over £60 million to be raised from this source. The Bank of England was to purchase another £40 million, which meant that £250 million had still to be raised from the general public and other sources. Disastrously, only £91 million was subscribed for, so the burden of taking up the remaining £159 million (virtually half of the entire issue) fell on the underwriting banks who managed to soak up a further £46 million. It was necessary to organise the remaining £114 million of stock to be personally taken up by two Bank of England officials, funded by secret loans from the Bank.

This failure was hidden from the public, but even this poor take up put the mechanism for issuing the paperwork under massive strain. Over 50,000 letters were received applying for the stock (40,000 of these were for the minimum subscription of £100). The history of the Bank of England states that:

The Bank's system of dealing with postal applications was ill suited to a loan so very much greater than any they had before issued, and considerable confusion at first resulted. Moreover, the frequency and consequent overlapping of the instalments made the agreement of the Ledgers difficult. It was found necessary to work on each of the five Sundays preceding Christmas Day , and a Staff of men - averaging 200 - was employed during the daytime.

With the First War Loan being far from successful, the Government reverted to issuing other forms of bonds to finance the war.

The issuing of a 3% Exchequer Bond (again with a discount on its face value) proved to be a failure in early 1915 (of the £50 million available, £38 million had to be taken up by the Bank of England). Somehow the Government had to find a way to tap into the nation's savings, but also make it logistically possible to do this by the Bank of England.

Second War Loan

The Second War Loan was issued in June 1915. Offering interest at 4.5% (but with no discount) it offered a superior yield to the First War Loan and was also firmly aimed at smaller investors from the broader population. It was possible to purchase this in multiples of £5 (and vouchers for 5 shillings, 10 shillings and £1 were issued). Because of the superior return, the Government conceded that holders of the First War Loan - and other gilts - could convert their holdings into this Second War Loan.

This Second 41⁄2% War Loan was to be repaid by the Government between 1929 and 1945, but a further concession was written into the prospectus which explicitly allowed holders to convert to any future issue should such a new issue be made on more favourable terms.

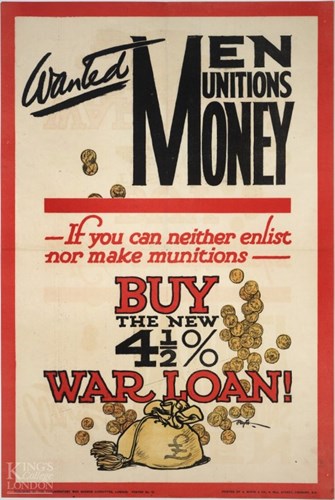

Publicity was cranked up a number of notches and the public were urged to buy the stock.

Between the prospectus being issued on 21 June 1915, and the closing date for applications, the Bank of England received an incredible 547,000 applications, totalling over £571 million (an average of £1000 per application). This "new money" loaned to the Government made the subscription highly successful (ten times more applications being received than for the First War Loan), but in addition, conversions from the First War Loan and other gilts of over £310 million meant that eventually over £900 million of this Second War Loan was issued (equivalent of £90 billion today). Of this total £900 million issued, a large proportion - £183 million - was again taken by UK banks. All this placed pressure on their balance sheets and curtailed lending to some sectors of the economy.

The average day staff employed on this issue by the Bank of England numbered 200, but this was wholly inadequate to cope with the paperwork. The space required for the process far outstripped the Bank of England's premises, and the use of the hall belonging to the Worshipful Company of Grocers was taken up in order to accommodate the 1,350 men and women employed each evening, of whom about 450 men were borrowed from outside Banks. It was also necessary to introduce a night-shift, with the first of these being worked on Saturday 24 July 1915.

Above: Bank clerks working on the allotment of 1915 war loan, Grocers' Hall, London © RBS

Above: Group of men from London County & Westminster Bank involved in war loan work at the Bank of England, 1915 © RBS

Below: Various posters promoting war bonds.

Using the Grocer's Hall was not a permanent solution, so the Bank of England had to locate new premises to house the army of staff needed to work on future issues. Fortunately a building erected for the Scottish Provident Institution in nearby Lombard Street came available, and part of this was taken over.

Above: The Scottish Provident Building, on the corner of Lombard Street and St Swithin's Lane, in London, was designed by the architect William Curtis Green in 1912.

Financing the War in 1916

The success of the Second War Loan meant that additional long term gilts did not need to be issued for about 18 months, and the cost of the war was financed through 1916 by the issue four classes of short term "Exchequer Bonds". These were the 5% Exchequer Bond 1920 (1920 being the year the Government was to repay the borrowing) - this was first issued in December 1915 and closed in June 1916. A total of £205 million was raised by this issue.

Immediately after the closure of the above Exchequer Bond, two further 5% Bonds were issued, one for repayment in 1919 and the other in 1921. Nearly £174 million was raised by these issues (over £17 billion in today's money). Of this £174 million, however, £77 million was an exchange by the banks for the money they had put into the Second War Loan - so in effect the 1919 and 1921 bonds raised only £97 million in "new" money.

A final Exchequer Bond was issue in October 1916, this offered interest at 6% and was scheduled for repayment in 1920. In just 3 months, this issue raised £161 million for the war effort.

Towards the end of 1916, it was suggested that Premium Bonds be issued, but Sir Robert Kindersley (chairman of the National Savings Committee from 1916 to 1920) kicked this idea into the long grass, among his objections being:

Very little was required in a nation of strained nerves to rouse a fever of gambling leading to extravagance, the lessening of self-control and the reduction of individual effort to work and to save.

The Third War Loan

Whether it was the failure of the Battle of the Somme to provide a decisive victory, or realisation that the war was going to grind on for some considerable time yet, can't be known, but by the end of 1916, it was becoming obvious that a major new loan would have to be raised by the Government to finance the war.

Issued as two alternative schemes, the first option offered a 5% interest rate, enhanced by the stock being offered with a five per cent discount - meaning £100 of stock could be bought for just £95 - this enhanced the return to over 5.25%. The second option offered interest at 4% (no discount was made) but the inducement here was that interest would be free of income tax. Both loans would be repaid, the Government stated, between 1929 and 1947.

A further publicity campaign was launched. The caption to the cartoon in 'Punch' (7 February 1917) below was hardly subtle.

Above: From Punch, Or The London Charivari, Volume 152, Feb. 7, 1917 (Artist: Fred Pegram, 1870-1937)

| A PLAIN DUTY. "WELL, GOODBYE, OLD CHAP, AND GOOD LUCK! I'M GOING IN HERE TO DO MY BIT, THE BEST WAY I CAN. THE MORE EVERYBODY SCRAPES TOGETHER FOR THE WAR LOAN, THE SOONER YOU'LL BE BACK FROM THE TRENCHES." |

Holders of the Second War Loan and the four Exchequer Bonds issued in 1916 could convert to the new War Loan. The Bank of England's history of the war[2] becomes almost animated on the matter:

"The campaign to popularise this Loan, which was in respect of size the greatest financial effort so far made by this or any other country, was wide-spread and energetically carried on. No less than 8.5 million Prospectuses, 20 million application forms of the various kinds and more than 3 million conversion forms were distributed."

The loan was made available from mid January to mid February, and by the time applications were made a staggering £960 million in "new money" had been raised (this is £96 billion by today's prices) - from just over two million individual subscribers (about £460 per subscriber, on average). This was more than the first two war loans combined and was more than ten times the amount raised from the public via the First War Loan. Only two percent of the applications went to the tax-free variation of the loan.

In addition to the new money raised, conversions of the second war loan and the Exchequer Bonds took the total issued by this Third War Loan to £2,128 million (or £2.1 billion). This was a vast sum in 1917 and in today's terms is about £161 billion.

The new money raised (£960 million) was around four times the entire national budget for 1913-14 but it came at a high price, the cost of servicing the interest on the £2.1 billion war loan would cost the government £106.4 million per year or £291,500 per day (equivalent to £22 million per day in 2015).

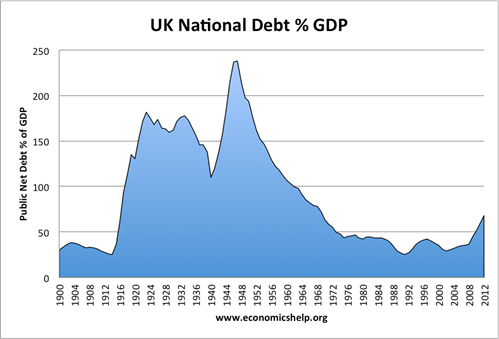

All of this borrowing totally transformed the nation's indebtedness which had been gradually falling during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. The chart below shows the result of Britain's National Debt as a percentage of the national income.

Premises to house the ever-increasing staff needed to issue and service the War Loan was found at Moorgate Hall.[3] The Bank of England's unpublished War History again:

"In dealing with the enormous task involved in the registration of the cash applications, the need of extra space at once became apparent, and large premises , which later proved inadequate, were accordingly taken at Moorgate Hall. The premises consisted of one very large room, 210 feet long, with distempered walls, bare floors and no fittings or light. The electricians at once began to arrange for the lighting, which was completed in five days.

Having obtained the room, the next step was to get a Staff. It was decided to employ temporary female labour in the daytime, and with this object in view, the Women's Service League was approached and a notification issued to other Women's agencies; also to the Staff of the Head Office, asking for help. On the first day (5 February 1917) 32 women were engaged, and this number was increased daily until after some three weeks it reached 365. Admission to the Staff was but little restricted, an applicant only having to satisfy the Bank that she was respectable and sufficiently educated to be capable of doing the elementary work required of her. Necessarily the standard was not a high one, and the results may therefore be regarded as satisfactory; for the work was done and the public served without the occurrence of many very serious mistakes. After the departure of the women each evening , their place was taken by a Staff composed of Civil Servants, Insurance Office Clerks and Clerks from other Banks, etc., whose hours were from 5 pm to 11 pm or later. On 5 February 1917 this temporary male staff numbered 210, but was increased until the maximum evening Staff employed on inscription at Moorgate Hall reached 417.

On Sunday 26 March 1917 two months after the Prospectus was issued, the great effort was completed and the 6,000 unbound Sections of ledger and the million index cards were collected from the various outlying offices into the Bank, ready for transfer operations which were to open on the next day."

Finance to the end of the War - National War Bonds

The success of the Third War Loan did not stop the Government from needing to receive continuing inflows of money, so in April 1917 a new Exchequer Bond (5%, repayable between 1919 and 1922) was launched. Despite being on offer for five months, these did not prove to be popular, and they raised less than £80 million. It was therefore decided to offer a new type of bond, which could be bought "over the counter" at high street banks - these were National War Bonds.

Above: War Bond Posters

These National War Bonds became available from October 1917. Initially there were four variations in the first series, paying interest at 4% (tax free) and 5%, with different maturity dates, but between 1922 and 1927. The issue of these was highly successful, in the first ten days, £35 million was raised from nearly 28,000 applicants (being an average of £1250 per applicant - a very large amount, equivalent to £95,000 today).

The pace of take-up did not diminish, and by March 1918 (when they were withdrawn) over £616 million of this first series of four war bonds was issued (not all of this was new money, as gilts with less than 6 months to run were accepted in payment, but as repayment of these near to maturity gilts was deferred by this conversion, this was in effect as good as "new money").

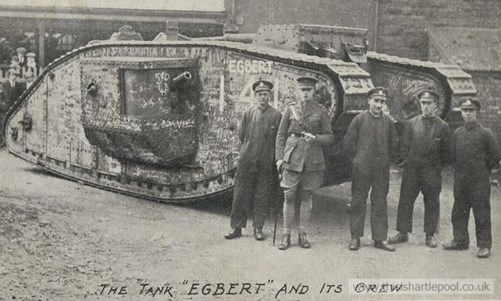

The marketing of these National War Bonds was undertaken by the National War Savings Committee, mentioned above.[4] The most successful marketing was inspired by the use of tanks. The first of these "tank banks" appeared in Trafalgar Square. The Bank of England described the first use of this as follows:

The first "Tank" experiment was made in Trafalgar Square during a fortnight of December 1917. A small hut about 8 feet square was erected, in which two Bank of England representatives and Post Office girls received subscriptions from the public who , after paying their money , were directed to the Tank where their receipts were stamped with a special " Tank" stamp.

The tank used "Egbert" (numbered 141) was a veteran of the Western Front, and reports of large subscriptions being made are recorded, including one old man bringing his life savings - £700 in Gold Sovereigns (equivalent to £53,000) - to invest.

Above: "Egbert". Courtesy of www.thisisHartlepool.co.uk

Egbert and five other tanks (113 "Julian"; 119 "Old Bill"; 130 "Nelson"; 137 "Drake"; 142 "Iron Ration") toured the country. Glasgow raised by far the largest amount of all the towns and cities visited, bringing in a total of over £14 million (out of a total of £55 million), however West Hartlepool was arguably the most successful - the £2 million raised there being equivalent to £37 per head of population.

Above: Old Bill (tank 119)

Tanks were presented to various towns after the war in recognition of the amounts raised.

Above: General Swinton presenting The War Savings Prize Tank "Egbert" to West Hartlepool. Courtesy of www.thisishartlepool.co.uk

Virtually all of these presentation tanks were sold for scrap or destroyed, during the Second World War. Only Ashford's tank still survives, mainly due to having an electricity substation built inside it in 1929.

Above: Mark IV Female Tank at Ashford by Peter Trimming

A second series of National War Bonds were issued in April 1918 (£483 million raised) and a third series in October 1918 (£494 million raised). A fourth series was issued in February 1919, but this brought in only £76 million).

The total amount raised from all sources by the National War Bonds across all four issues was £1,731,726,376 (£1.7 billion). In today's money this is equivalent to £105,000,000,000 or £105 billion.

Funding and refinancing the national debt after the war became a massive exercise, but is outside the scope of this article.

Conversion of The Third War Loan - 1932

The three War Loans plus the issue of the National War Bonds were the principal ways the UK Government obtained money from the general population (either directly or via banks converting their deposits into these bonds) during the war. The cost was high. Interest rates of 5% were offered on the Third War Loan (a large proportion of the previous two War Loans had been converted by the holders into this bond) and cost of servicing this debt was - during the Great Depression of the 1930's - unsustainable. Nor could the Government repay the massive loan it had incurred (although the option to do so was exercisable by the Government from 1929 onwards - matters would come to a head in 1947 when it would have to be repaid).

Interest payments on the Third War Loan were absorbing 40% if all money collected by income tax. In the summer of 1932 the Chancellor of the Exchequer (and future Prime Minister) Neville Chamberlain announced a conversion offer for the entire Third War Loan (which was paying 5%) into a new issue, bearing interest at only 3.5%, but - uniquely - without any specific maturity.

Chamberlain set out to persuade War Loan holders to convert to the new issue as a matter of patriotic duty. It was also announced that those who did not refuse the offer would be deemed to have accepted it anyway. With interest rates at the time being only 2%, the 3.5% offered (with no maturity date) looked attractive.

The government even created a War Loan Conversion Publicity Bureau, to convince the public to accept the deal.

The propaganda was highly successful. Mounted policemen had to be called out to control the queues that formed to convert to the new stock. Not everyone was taken in. The economist John Maynard Keynes described the operation “a bit of a bluff which a fortunate conjunction of circumstances is enabling us to put over on ourselves.”

Over ninety per cent of the holders of the Third (5%) War Loan converted into the new 31⁄2% War Loan, which by the terms of their issue did not need to be paid off.

Conclusion

Does the announcement that the War Loan will be "paid off" stand up to scrutiny? Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne has stated that by undertaking this exercise, the £1.9 billion currently outstanding to over just over 11,000 registered holders means the First World War is now paid off.

There are two problems with this statement. The first is that the value of the £1.9 billion - a phenomenal amount in the 1930's has been depreciated to the value of "small change" (at least in Government budget terms) by 2015. Inflation has - over time - dissolved the mill-stone of this debt. Whilst the interest on this has been met since 1932 (and before this in the War Loan's earlier forms) the annual value of the interest payments has - like the capital value of the War Loan stock held by so many of the population - also reduced. Anyone who converted into the War Loan in 1932 would have received £35 per year for every £1000 invested, but the £1000 that was invested at the time and is now being repaid is now worth only a fraction of the £1000 that was handed over to the Government in 1932. The value of goods and services that you can now obtain for £1000 would have cost less than £17 in the 1930s. (By the same token, the £35 interest in the first year - under this example - would require £2000 in 2015 to buy the same amount of goods and services).

The second point is that the debt is not being paid off. The repayment of the Consols and War Loan earlier in 2015 simply merged debt which had no maturity date into other government borrowing which will cost less to service. This is just a book keeping exercise and the residual and identifiable costs of this have now been swept up into a bland and unremarkable new gilt which will - in its turn - be refinanced again in perhaps twenty or thirty years' time.[5]

What comes out of this study is the incredible amount of capital the Government required to wage the war 100 years ago, and the effort needed to administer the raising of this amount of capital in the days when this kind of work was done manually and without the aid of modern technology.

The final point to note is that the male dominated world of banking was broken down in the war and the employment of women became - if not normal - accepted. That, however, is another story entirely.

Above: Female staff at Cox's & King's Charing Cross office in 1918 - something that would not have been seen before the outbreak of the war.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

FOOTNOTES

[1] The public were able to convert notes into gold at banks: with war looming, many people sought safety in holding gold rather than pieces of paper.

[2] The Bank of England 1914-21 (Unpublished War History) Archive Catalogue Reference: M7/156-159. Finished in 1926, the work was never published. Three ‘fair‘ typescript copies of this four volume history were bound and given to The Governor, Deputy Governor and Comptroller. Three copies of lower quality ‘flimsies’ were bound less lavishly and given to the Chief Cashier, Chief Accountant and Secretary. The Bank’s Archive now holds three of the bound sets.

[3] The Moorgate/Lothbury site was assigned to the National Debt Office, part of the burgeoning state machine that was needed to administer the war effort - this is now the site of the Arab Banking Corporation's London office

[4] The National Savings Movement was created in March 1916 as the National Savings Committee and this was supplemented by volunteer local committees and paid civil servants. A number of different organisations were loosely affiliated to make up the movement.

[5] Notes on the Redemption:

4% Consolidated Loan was issued initially by conversion from 5% Treasury Bonds 1927, 5% National War Bonds 1927 and 4% National War Bonds 1927 in 1927. The government has held an option to redeem the bond since 1 February 1957.

3½% War Loan was issued by conversion from 5% War Loan 1929-47 in 1932. 5% 1929-47 was itself issued in 1917 as part of the financing of the First World War. The government has had the option to redeem 3½% War Loan since 1 December 1952.

Source: United Kingdom Debt Management Office Press Releases 31/10/2014 and 3/12/2014.