The Kinmel Park Riot of Canadian Servicemen March 1919

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Kinmel Park Riot of Canadian Servicemen March 1919

The events at Kinmel Park in North Wales in March 1919 were the most serious instance of a number of riots or disturbances that took place in the UK involving Canadian servicemen between November 1918 and June 1919.

With the Armistice signed on 11 November 1918, many troops eagerly anticipated their repatriation, none more so than Canadians troops stationed at Kinmel Park in North Wales. Not only were they still far from home, but the ‘Spanish Flu’ epidemic of 1918/19 was prevalent, with around 80 deaths occurring amongst those stationed at Kinmel. In addition, the winter of 1918/19 was severe.

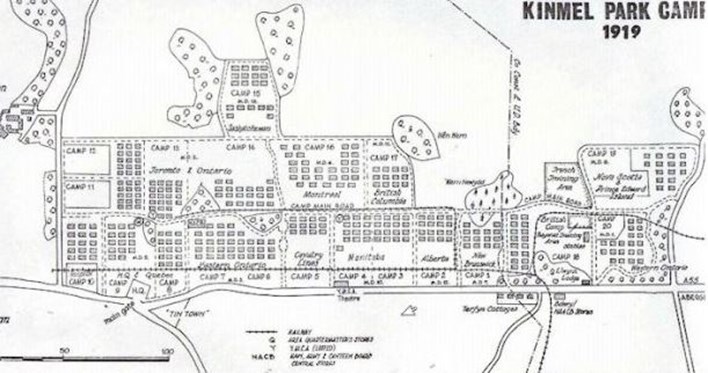

Kinmel Park Camp had been in existence since early in the war. By the end of 1918 it was utilised as a staging camp to house Canadian service battalions prior to their repatriation. The camp covered an extensive area and comprised 20 sub camps, each with their own accommodation, mess halls and training facilities, all built of timber. There was also a large military hospital on site.

Plan of Kinmel Park camp Courtesy of J.J. Putkowski, The Kinmel Park Camp Riots 1919 (Flintshire Historical Society, 1989)

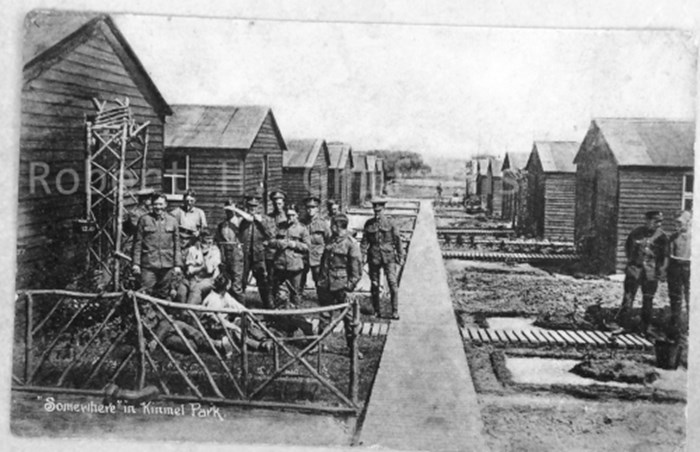

Entrance to Camp

Accommodation huts

A YMCA hut in the camp

Outside of the camp, a shanty like ‘tin town’ had sprung up – a collection of shops and pubs set up to cater for the thousands of troops stationed in the camp.

By early 1919, the mood of many of those in the camp was becoming restive – the camp was overcrowded, food was poor, compared unfavourably to ‘pigswill’, the traders in ‘tin town’ had raised prices, perceiving that Canadian soldiers were better paid than British troops (although their pay was often late), the days were filled with exercises which many thought meaningless and of course, all wanted to return home to their families, acutely aware that jobs would be snapped up by those lucky enough to get home more quickly. To compound this, there was a shortage of experienced camp commanders and NCOs.

By late February, it became common knowledge that a number of large ships had been reallocated to American troops – who had not been overseas for as long as the Canadians. Then, at the beginning of March, a decision was made to transport the 3rd Division Infantry back to Canada - although these men were combat troops, they hadn’t been overseas as long as many of those at Kinmel Park.

All of these factors coalesced on 4 March 1919 when Sapper William Tarasevich was chosen to be the leader of what would later be described as a riot, with looting and vandalism taking place within the camp itself and outside in ‘tin town’.

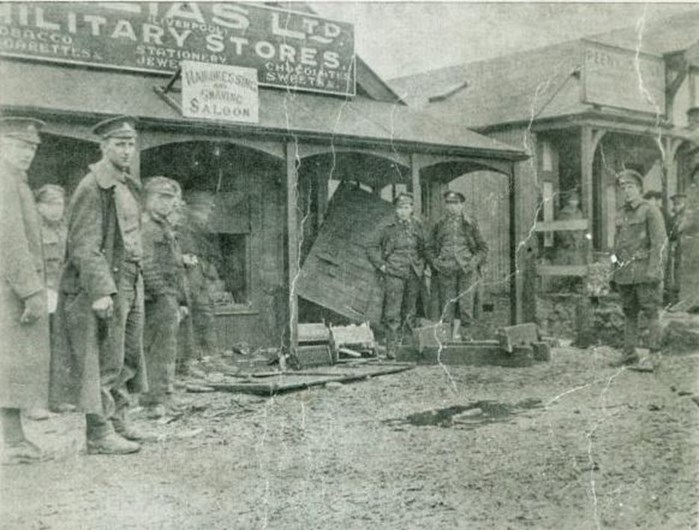

Aftermath of disturbances in the Camp

Damage to 'tin town'

The events of 4 and 5 March left five men dead (all died on 5 March 1919), twenty one wounded and seventy eight under arrest. Of those arrested, twenty five were found guilty of mutiny and were given sentences ranging from 90 days imprisonment to 10 years penal servitude, although a number of these sentences were later reduced. No charges were brought in relation to the deaths which occurred and none of the later inquiries produced any conclusive findings on who was responsible for the deaths. The vast majority of the Canadians at Kinmel Park returned to Canada by the end of March 1919.

Surprisingly, one of those killed in the riot is buried in Canada.

Gunner John Frederick Hickman was born in New Brunswick, Canada. He enlisted in April 1916 and served in France with the 58th Battalion from July 1917. It appeared that he had been killed by a stray bullet and was later exonerated from any part in the riot.

Entrance to Dorchester Cemetery

John Frederick Hickman's headstone

The other four of those killed in the course of the disturbances are buried in the nearby churchyard of St Margaret’s Church at Bodelwyddan.

Canadian graves in St Margaret's Cemetery, Bodelwyddan

The grave of Sapper William Tarasevich is also located in this cemetery.

Headstone of William Tarasevich at Bodelwyddant

Sapper William Tasarevich was born in Russia in 1889. He enlisted in Montreal in January 1917 and served in France with the 4th Canadian Railway Troop. His service record indicates that he was accidentally killed during the disturbances. A medical report indicates that he died as a result of a bayonet wound to the abdomen.

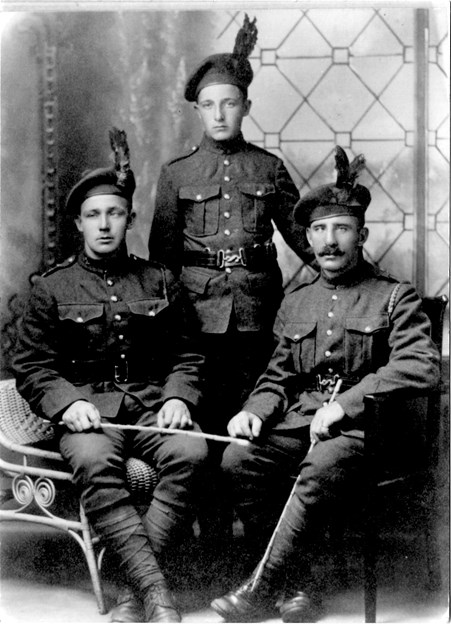

Private David Gillan was born in Lanarkshire, Scotland. His family had emigrated to Canada in 1903 and had enlisted in Nova Scotia in March 1916, serving in the 85th Battalion in France from March 1918. During the riot, David was on guard duty and sustained a bullet wound to the neck.

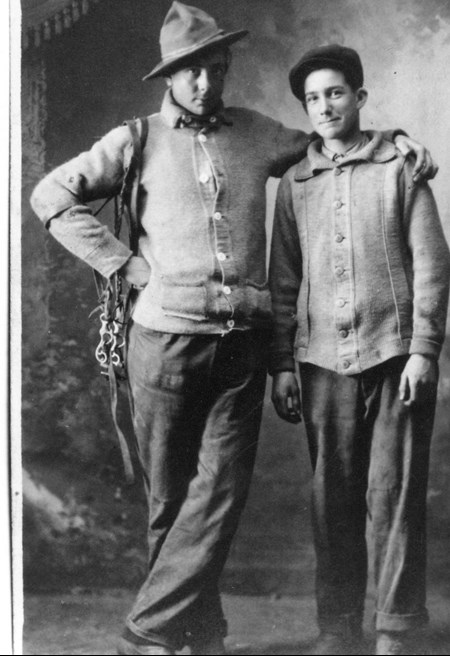

David Gillan (pictured centre)

Gavid Gillan's gravestone

Gunner William Lyle Haney was born in North Dakota, USA. He enlisted in Calgary in February 1918 and had served at Witley Camp in England. He was killed by a bullet wound to the head.

Joseph Young (pictured left)

Private Joseph Young was born in Glasgow. He enlisted at Port Arthur in April 1915 and served in France with the 52nd Battalion from February 1916. He died of a bayonet wound to the head.

Joseph Young's gravestone at Bodelwyddan

The inscription on his grave is ‘Sometime, sometime, we’ll understand’, words from the refrain of a hymn composed by Maxwell Cornelius in 1891 of which the second verse may be better known -

‘We’ll catch the broken thread again.

And finish what we here began,

Heav’n will the mysteries explain,

And then, ah then, we’ll understand’.

Article by Jill Stewart Hon Secretary, The Western Front Association

Sources and further information

Far from Home Project: A Study of First World War Canadian War Graves in the UK

Canadian War Graves Bodelwyddan