The Loss of HMS Pathfinder

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Loss of HMS Pathfinder

Within 24 hours of the declaration of war, on the 5th August HMS Lance, a Royal Navy destroyer, fired the first British shot of the war in action against the Koningen Louise, a German minelayer. The next day, HMS Amphion, a cruiser, became the first Royal Naval warship to be sunk in the war – having hit one of the Koningen Louise’s mines. Exactly a month later on the 5th September the light cruiser HMS Pathfinder was sunk off the East Coast of Scotland.

HMS Pathfinder which has been launched in 1904 and commissioned the following year, had the dubious distinction of being the first warship to be sunk by a submarine launched self-propelled torpedo. Other ships had been sunk by torpedoes, and submarines had also been responsible for the sinking of enemy warships, but this was the first successful submarine launched torpedo attack.[1]

On the morning of September 5 1914 HMS Pathfinder and the vessels of the 8th Destroyer Flotilla carried out a sweep of the outer Firth of Forth Estuary.

Above and Below: HMS Pathfinder (IWM Q 75425)

Unknown to the British, German submarine U-21 , commanded by Otto Hersing penetrated the Firth of Forth as far as the Carlingnose Battery beneath the Forth Bridge with the intention of seeking targets at the Rosyth Naval Base.

Whilst the U-21’s periscope was spotted and the battery opened fire, no hits were made on the U-21 and the submarine withdrew from the estuary.

Above: Otto Hersing, the Submarine commander responsible for the sinking of HMS Pathfinder.

On September 5, 1914, U-21 was sitting on the surface, charging her batteries using diesel generator when her crew spotted a smudge of smoke in the distance. They immediately dived, and sat just below the surface preparing to attack. However, the warship – which was HMS Pathfinder (followed by elements of the 8th Destroyer Flotilla) - changed course, using a zigzag to avoid enemy submarines. U-21 could not make an attack, as her submerged speed was less than 10 knots compared to the Royal Naval warship’s 27 knots. The line of destroyers behind her turned towards Rosyth and HMS Pathfinder continued her patrol.

Later that day, Hersing spotted Pathfinder on her return journey from periscope depth at 3.30pm, and this time he was determined to make an attack, Pathfinder came within range and just thirteen minutes later he ordered a single torpedo to be fired.

On board HMS Pathfinder, no doubt the crew were reasonably relaxed, the afternoon had proved to be sunny and the patrol had been uneventful. However, at 3.45pm, the Pathfinder’s lookouts spotted a torpedo wake heading towards the starboard side of the ship at a range of 2,000 yards (just over a mile). The officer of the watch, Lieutenant-Commander Favell ordered the starboard engine to be put astern and the port engine to be set at full ahead this manouvre was to try to turn into the path of the torpedo and avoid being hit. This proved to be futile.

At 3.50pm the torpedo detonated beneath the Pathfinder’s bridge.

Pathfinder was rocked by the explosion. Immediately after the torpedo hit, a second explosion took place, this time from the forward magazine. Cordite bags, used as a propellant in the ship’s guns, had caught fire and caused everything in front of the first funnel to disintegrate.

Above: A painting depicting HMS Pathfinder exploding Art.IWM 5721 (IWM)

Most of the crew had no chance to escape. Although the explosion was within sight of land, Captain Martin-Peake knew it was essential to attract attention, so he ordered the stern gun to be fired but this must have been damaged by the explosion because, after firing a single round, the gun toppled off its mounting, rolled around the quarter deck, and went overboard, taking the gun crew with it. There was no time to lower the warship’s lifeboats.

Only five minutes after the impact, groaning and tearing noises from below signalled that the forward bulkheads had collapsed – those who survived the explosion must have known that HMS Pathfinder was doomed.

Fishing boats from nearby Eyemouth were soon on the scene but found nothing but debris, fuel oil, clothing and a handful of survivors. Two Royal Naval destroyers HMS Stag and Express also headed for the pall of smoke.

Above: HMS Arab, a sister ship to HMS Express

Above: HMS Stag

The Times stated that 58 men had been rescued but that four had died of injuries however this is not possible to verify due to there being no definitive list of the crew on that day. CWGC lists 261 fatalities from the Pathfinder, including two civilian catering staff.

One of the handful of survivors was Staff Surgeon Thomas Aubrey Smyth who gave an account of his experiences in a letter to his mother who lived at Bedeque House, Dromore.

Above: Staff Surgeon Thomas Aubrey Smyth

“The explosion blew a great hole in the side of the ship. I was at the time in the wardroom, but ran up on deck immediately, and it was then evident by the way the bow was down in the water that she would sink rapidly. I should say the whole thing occurred in about ten minutes which time was spent in throwing overboard the few articles which would float (the reason there was not more of these was that in preparation for war all unnecessary woodwork is got rid of to prevent fire). I was then thrown forward by the slope of the deck and got jammed beneath a gun (which I expect is the cause of my bruising) and while in this position was carried down some way by the sinking ship, but fortunately after a time I became released and after what seemed like interminable ages I came to the surface, and after swimming a short time I was able to get an oar and some other floating material with the help of which I was just able to keep on the surface. After holding on for a long time – I believe it was an hour and a half – I must have become unconscious for I have no recollection of being picked out of the water. You see we were alone when it happened, so it took a long time for the reserve torpedo boats to come out and it was too quick to get any of our own boats out, besides most of the few we had were splintered into pieces.”

Another of the survivors of HMS Pathfinder was Captain Francis Martin Leake who stayed with his ship as she went down but was luckily picked up and saved. He wrote in a letter to his mother:

“The torpedo got us in our forward magazine and evidently sent this up, thereby killing everyone forward”

Above: Captain Francis Martin Leake

He went on; “[Pathfinder] then fell over and disappeared leaving a mass of wreckage all around, but I regret very few men amongst it, for at the time they were all asleep on the mess decks and the full explosion must have caught them, for no survivors came from forward.”

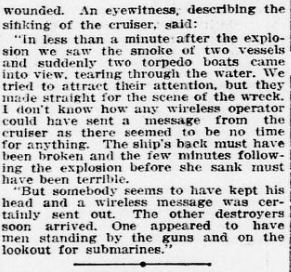

A seaman who escaped gave this account of his experiences:

"I saw a flash, and the ship seemed to lift right out of the water. Down came the mast and fore-funnel and forwards part of the ship. All the men there must have been blown to atoms. I bobbed down for a few seconds for fear of being hit by the debris - some pieces of it must have weighed nearly a hundredweight - which was blown sky high. I scrambled to the quarter-deck, which was littered with mangled bodies, and looked about for something to cling to. The Captain shouted 'To the boats.' But there were only two, and they were smashed. The other boats, and practically all the woodwork, had been left ashore. We fired a gun as a distress signal. By this time the ship was almost covered with water. 'Every man for himself' and I at once pulled off my boots, coat, and trousers, and over I went. I think I broke all swimming records, trying to put as much space as possible between myself and the ship, being afraid of suction. "Turning round, the last I saw of the ship, about fifty yards away, was the after-end sticking upright in the air about one hundred feet. Then it gradually heeled over towards me and sank. Then I swam again to get out of its way, thinking the end might hit me as it came down. It cleared me all right. It was all over in about five minutes from the start. When she sank, something blew up, and on came a wave, and round and round I went like a cork. A bouy came speeding by me. I grabbed it, and that was what kept me afloat."

Lt Stallybrass recalled that the bulkheads held firm until five minutes after the big explosion:

The ship gave a heavy lurch forward and took an angle of about forty degrees down by the bow. Water came swirling up to the searchlight platform. The Captain said, ‘jump you devils jump !’. The Captain and his secretary [probably Paymaster Alan Bath] remained with the ship until the very end but somehow both survived”

In his ship’s log, Hersing described what happened.

“At around 3 PM in the afternoon, my second in command was on bridge duty and was doing a normal scan of the waters with the periscope. He noticed a British vessel called HMS Pathfinder. At the moment, we were at about 10 meters below surface and in a very vulnerable position. We believe that they noticed us because they turned around in our direction. My second in command immediately called upon me and I answered him speedily. I rushed to the bridge and told the helmsman to submerge. It was a British light cruiser and it seems it was equipped with cannons and machine guns and probably depth charges. When we reached 50 meters, we fired one torpedo and destroyed the vessel. We soon surfaced and saw about 100 people. We believe there was a crew of about 600+ people thus this would seem that the British just had a very heavy loss of life.”

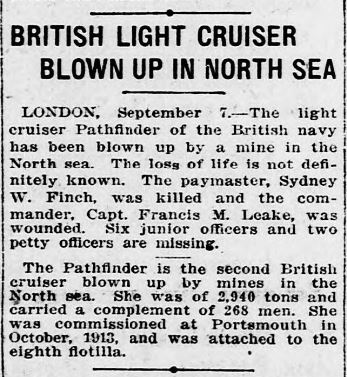

Official communications were made and published in the following days:

Above: Evening Star, Washington, 7 September 1914

Above: Report from the Evening Star, Washington, 8 September 1914, page 9

Fatalities

Four men died of injuries or exposure and are buried at South Queensferry (two are 'unknown')

Above: Queensferry Cemetery, where there are two named headstones to men from Pathfinder. (CWGC)

Another fatality of the sinking is buried at Warriston near Edinburgh, one man is buried at Bridlington on the Yorkshire coast, and another in Plymouth. This means that of the 261 listed fatalities, only five have known graves: it is possible bodies were washed ashore for some weeks, indeed one unknown Pathfinder sailor is buried at Dunbar on the Forth estuary within sight of the scene of the sinking.

Some of those killed include:

Chief Engine Room Artificer 2nd Class Basil Hovenden Neve

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

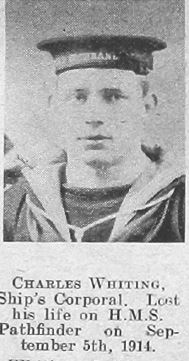

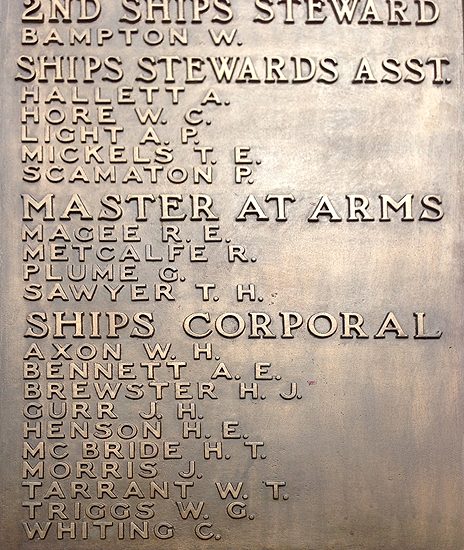

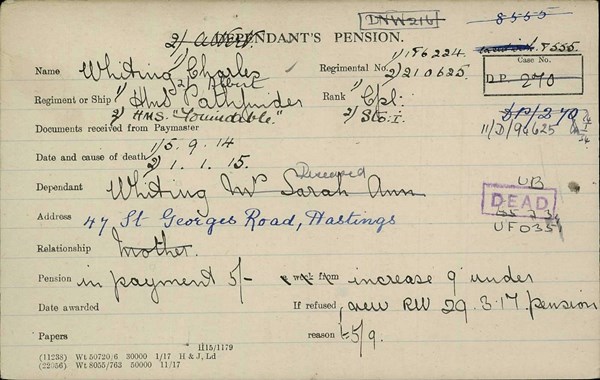

Ship's Corporal 1st Class Charles Whiting

Above image courtesy of WW1 Roll of Honour

Above: Detail from the Chatham Memorial – Charles Whiting’s name is at the bottom of this panel. (Master at Arms Richard Magee is also one of the Pathfinder fatalities on this panel).

Charles, from Hastings, was one of two brothers who both died within three months of each other whilst serving in the Royal Navy.

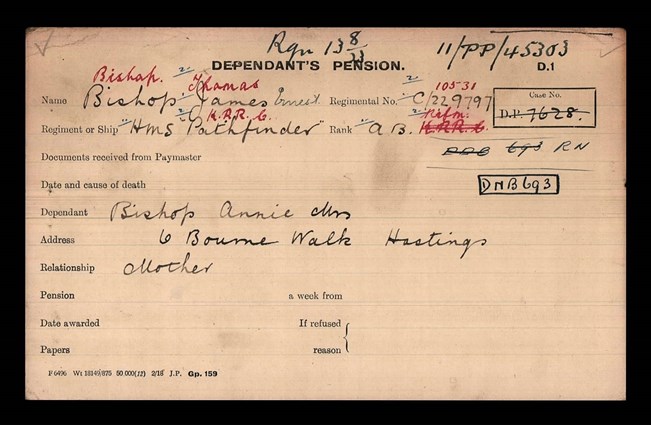

Also from Hastings was Able Seaman James Bishop

Above image courtesy of WW1 Roll of Honour

As can be seen on this Pension Card, James also had a brother, Thomas, who was killed whilst serving in the KRRC in October 1918.

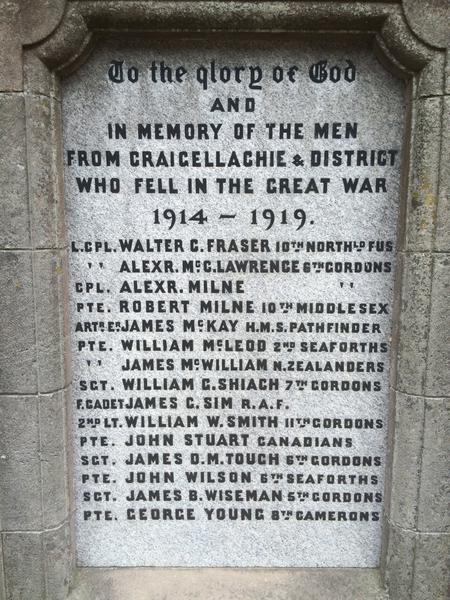

Artificer Engineer James McKay

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

Artificer James McKay was the son of Peter and Helen McKay. He was born in Boharm in April 1881. His family later lived at Fiddich Cottage, Craigellachie. As a young man, James showed a marked proficiency in maths and served an engineering apprenticeship in Perthshire. From there, he worked at Chatham for the Admiralty for around thirteen years and for 18 months, he had been master of works at Fairfield Shipbuilding Yards in Glasgow.

McKay is named on the Craigellachie War memorial

Above and below: The Craigellachie War memorial

Yeoman of Signals Roderick Donald Lardner

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

Able Seaman Henry John French

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

Able Seaman Peter Forsyth

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

Lieut-Commander Ernest Torre Favell

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

Ordinary Seaman Edward Duck

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

Ordinary Seaman Herbert Daley

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

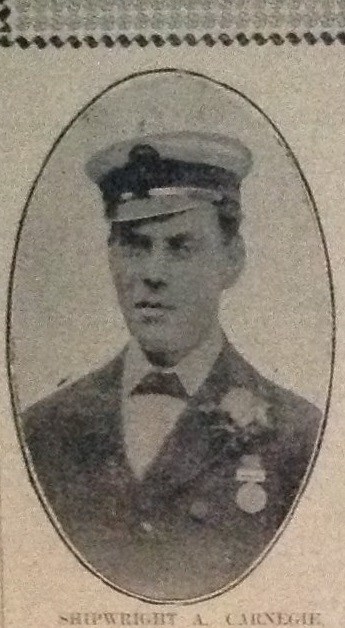

Shipwright 1st Class Alexander Carnegie

Above image courtesy of Lives of the First World War

Lt Gerald Leather

Above image courtesy of UK Photo Archive

The vast majority of the men are commemorated on the Chatham Memorial

Above and below: The Chatham Memorial (above WW2 cemeteries, below author's collection)

The Wreck

The wreck is upright and in reasonable condition but it is wreathed in net. The entire fore section ahead of the first funnel was destroyed by the explosion.

Parts of the teak deck remain with metal grilles embedded above the engine space at the stern.

A 6 pdr gun can be seen on deck and, further aft, a 4” gun remains on its mounting.

The superstructure has disappeared but here and there the outlines of a battery casemate, gaping hatchways, gun indicator telegraphs.

The sediment filled recesses marking the positions of the funnels are evident.

The starboard torpedo tube has been wrenched off by nets but the port tube remains on its mounting. The decks are littered with ammunition and remains of the funnels. Rope can still be seen on an intact lifeboat davit.

Above: Images from the wreck site, courtesy of War History Online

There is a video of a dive on the wreck of HMS Pathfinder (click the 'play' button to watch)

Conclusion

The sinking of HMS Pathfinder on 5 September would been easily visible from anyone on the nearby coastline, but nevertheless the Government was keen to change the narrative. It was initially said that the warship had been mined. The First Lord of the Admiralty (Churchill) imposed a censorship of all reports. Unfortunately The Scotsman went against this and published an account by an Eyemouth fisherman who had helped in the rescue. The account confirmed rumours that a submarine had been responsible, rather than a mine. However The Scotsman also for some reason reported that HMS Pathfinder had been attacked by two U-boats and had accounted for the second one in her death throes. The Admiralty latched onto this and spun the story that the U-boat responsible had been located and ‘shelled it to oblivion’.

Article by David Tattersfield,

Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Footnotes

[1] Although this was the first time that a submarine has torpedoed a warship, it was not the first time that a motorized torpedo has been used to sink a vessel. That distinction belongs to Russia, which sank a Turkish steamer in 1878 by using a fast, motorized boat to fire a self-propelled torpedo. The first time a submerged submarine has fired a torpedo was in 1888 by the Ottoman ship Abdul Hamid .

Facts and Figures on HMS Pathfinder

Displacement: 2,940 tons

Length: 385 feet (117.3m) overall

Beam: 38.4 feet (11.7m)

Draught: average 13.8 feet (4.2m)

Complement: 270 (268 at time of loss)

Armament: 9 4-inch guns, 2 18 inch torpedo tubes

Propulsion: Two 4 cylinder triple expansion oil fired steam engines driving twin screws

Speed: max 25 knots

Armour: 2 inch belt, 0.6-1.5 inch deck