The Loss of the Britannic : 21 November 1916

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Loss of the Britannic : 21 November 1916

Some years ago there was much publicity around the 100th anniversary of the loss of the RMS Titanic, which sank in April 1912 after striking an iceberg.

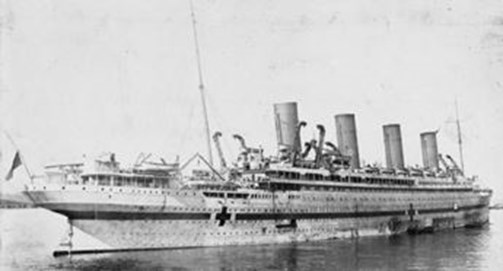

What is less well know is that the Titanic’s sister ship, the Britannic was also lost during the course of the First World War on 21 November 1916. Britannic was almost identical to the Titanic, measuring 882 feet in length, and having a displacement of over 53,000 tons.

Following the loss of the Titanic, numerous design changes were incorporated into the Britannic, these included making the hull double-skinned in the area of the engine rooms and raising five of the watertight bulkheads as high as ‘B’ deck, 40 feet about the waterline - all this meant she should be capable of remaining afloat with as many as six compartments flooded. Massive new davits were installed, each being capable of launching six of the largest lifeboats yet fitted to a liner. Britannic was launched at the Harland and Wolff shipbuilders complex in Belfast in February 1914 but, because of these and other changes (and also because of the outbreak of the war) she was not finally completed until the end of 1915.

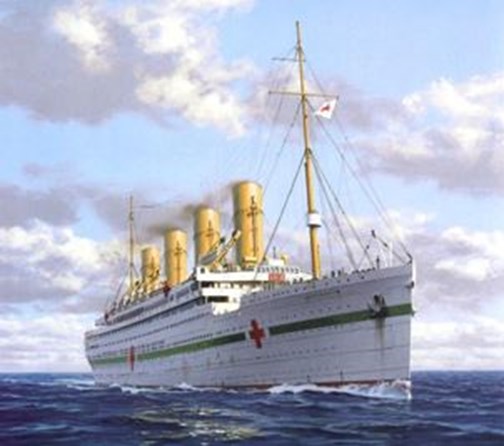

On 13 November 1915, Britannic was requisitioned in order to be used as a hospital ship. Much work had to be done to prepare her ready for her new role, this included the installation of extra davits capable of holding even more lifeboats and repainting her hull white. She also sported a horizontal green stripe and three large red crosses down each side. The first class dining rooms were converted into operating theatres and ‘B’ deck would be home for the medical staff.

Adjusted original photo of Britannic showing her colour scheme.

Under the orders of her Captain, Charles Bartlett (known as ‘Iceberg Charlie’ to his crew), the maiden voyage of HMHS (His Majesty’s Hospital Ship) Britannic started on 23 December 1915 when she left Liverpool for Mudros, on the Greek Island of Lemnos, off the Gallipoli coast.

Above: Captain Charles Bartlett

This was the first of two voyages that she was to make in support of the Gallipoli campaign. Her capacity to transport wounded soldiers was vast: over 3,300 patients could be carried on each trip. Although the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula in January 1916 resulted in her not being required for casualty evacuation of troops from the Dardanelles, the opening of the Salonika campaign meant that she was still needed in the Eastern Mediterranean; she was to complete a further three trips to evacuate troops from this theatre, bringing back over 10,000 men.

Another view of Britannic, again courtesy of the Imperial War Museum HU90768. Note the large davits capable of holding numerous lifeboats.

Sailing from Southampton (there was a large Military Hospital at Netley, just outside Southampton) Britannic’s sixth voyage– still under Captain Bartlett – commenced on 12 November 1916.

Passing Gibraltar on the night of 15/16 November, she arrived at Naples on Friday 17 November where she took on coal. A storm kept her in port until Sunday but the storm seemed to lift and she left port on Sunday the 19th and set off on the final leg of her voyage, heading for the massive natural harbour at Mudros (which was still being used as the collecting point for all Eastern Mediterranean casualties). Just two days later, Britannic was sailing close to her full speed in the Kea Channel, about 40 miles southeast of Athens and less than five miles west of the island of Kea.

Britannic, Hospital Ship. Painting by Ken Marshall, courtesy of Madison Press Books.

On Tuesday 21 November, just after 8am, Bartlett was on the bridge, along with Chief Officer Hume and Fourth Officer McTowis, when a loud explosion was heard – something had hit the ship on the starboard side, near the bow between the second and third cargo holds. Damage to a bulkhead meant that the first five compartments would become flooded. The timing of the explosion was to be fatal: watertight doors between boiler rooms were open to allow shift changes to take place.

Bartlett instructed that distress signals be sent and ordered the shutting of all watertight doors – although badly damaged, the ship should still be able to be saved. Unfortunately, doors between boiler rooms five and six failed to shut. This meant that the maximum of six compartments were now flooding. This was still survivable; as the ship took on water the list to starboard increased and within quarter of an hour, the water was lapping at the portholes on decks ‘E’ and ‘F’. Some of these portholes had been left open by nurses to allow fresh air to circulate in readiness for the casualties that would be shortly coming on board. This exacerbated the already critical situation.

As she had been hit just a few miles away from the island of Kea, Bartlett ordered the ship to be steered towards the island hoping to beach her there. On the boat deck crew members were preparing for the expected order to abandon ship: some boats were lowered towards the sea, but seeing the propellers were still turning, these boats were stopped about six feet from the surface of the water.

At 8.30am, using automatic lowering gear, the occupants of two of the lifeboats lowered their craft into the sea. Not immediately aware of the danger, the occupants watched the Britannic slowly continue its way. At the last moment the occupants must have realised they were in mortal danger: the ship’s propellers – still turning – had been forced above the surface by the sinking bows. These two boats drifted into the propellers and were smashed.

Painting by Ken Marshall, courtesy of Madison Press Books.

Realising that the Britannic was on the point of sinking that she would not make Kea, and that further casualties may be incurred by the propellers, Bartlett ordered the engines to be stopped and the lifeboats lowered. The order to halt the engines was carried out just in time for the occupants of a third lifeboat which was about to be reduced to matchwood. Pushing against the now static propeller blades, the relieved survivors floated away from the Britannic.

Bartlett ordered the ship to be abandoned at 8.35am, just twenty three minutes after the explosion. Over the next half hour, the 600 crew and 500 medical personnel clambered into thirty-five lifeboats or swam for their lives away from the fast-sinking ship.

Lifeboats being launched from the Britannic.

Violet Jessop, a nurse, was on board one of the two lifeboats that were destroyed by the propellers. Realising the danger just in time, she dived clear and was sucked below the waves. Coming to the surface, she hit her head on the keel but was rescued by another lifeboat. The last moments of the Britannic were described by Violet:

"She dipped her head a little, then a little lower and still lower. All the deck machinery fell into the sea like a child's toys. Then she took a fearful plunge, her stern rearing hundreds of feet into the air until with a final roar, she disappeared into the depths, the noise of her going resounding through the water with undreamt-of violence...."

Remarkably, this was not the first time Violet had survived a wreck, she had been on board the Titanic four years earlier!

Violet Jessop

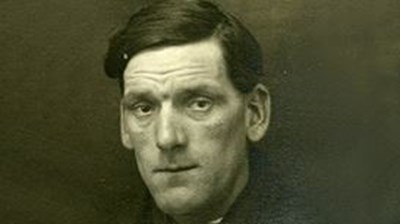

Also surviving both the Titanic and the Britannic sinkings was John Priest, a stoker. Priest, has also left an account:

"... most of us jumped in the water but it was no good we was pulled right in under the blades...I shut my eyes and said good bye to this world, but I was struck with a big piece of the boat and got pushed right under the blades and I was going around like a top...I came up under some of the wreckage ... everything was going black to me when someone on top was struggling and pushed the wreckage away so I came up just in time I was nearly done for ... there was one poor fellow drowning and he caught hold of me but I had to shake him off so the poor fellow went under.”

John Priest, a survivor of the Titanic and Britannic. Image courtesy of the BBC

Incredibly, a third person survived both the Titanic and Britannic sinkings. Archie Jewell, the lookout, was to be less fortunate in 1917 - he was drowned when he was involved in another shipwreck.

Archie Jewell – image courtesy of encyclopedia titanica

Major Harold Priestley, who had taken charge of the medical orderlies, ensured the evacuation was carried out in an controlled manner. He supervised part of the operation, allowing 50 men at a time up onto the boat deck. One of the last men to leave the Britannic was Private Holmes Brelsford of the RAMC. Brelsford and seven of his comrades assisted Major Priestly to jettison life rafts and deckchairs overboard in the final stages of the ship's sinking. Brelsford and Priestley were among the occupants of the last lifeboat to be lowered at about 9.00am.

Captain Bartlett was still manning the bridge and controlling the evacuation with the aid of a megaphone. He gave one final blast on the ship’s whistle and stepped into the water as the Britannic slipped beneath the waves at 9.07, less than an hour after being damaged. All the improvements in design since the loss of the Titanic had not been enough to save the Britannic. Bartlett swam to a lifeboat and continued to coordinate the rescue.

A local fishing boat was the first to arrive on the scene, but larger vessels soon came along, including HMS Heroic and HMS Scourge. These two warships, together with two French tugs, arrived at 10am and between them, picked up over 800; they headed for Piraeus, on the mainland, crammed with survivors.

Survivors of the Britannic. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q93209

Of the 1,066 crew and medical staff on board, only 30 (21 crew plus one officer and eight men of the RAMC) were to lose their lives; most of these were probably in the lifeboats that drifted into the propellers.

For many years the cause of the explosion was unknown. Some reports at the time talked of the track of a torpedo being seen just before the explosion, but recent dives on the wreck have revealed chains which almost certainly indicate that mines tethered to the bed of the sea, probably laid by German submarine U-73, caused the explosion. Regrettably, diver Carl Spencer died whilst investigating the wreck in 2009.

Being so close to the shore as indicated here, Britannic is relatively near the surface – at less than 400 feet which is less than half her overall length.

The wreck of the Britannic lying on the sea bed off Kea. Image courtesy of Britannic wiki

Britannic was the largest vessel to sink during the Great War; there was no catastrophic loss of life, unlike with the Lusitania, and no deliberate targeting of a Hospital Ship was evident (although the concept of a torpedo attack remained a possibility for many decades). As a result the story of the Britannic is now largely forgotten.

Listed below, for the first time, is a list of all those who perished in HMHS Britannic.

The Britannic Roll of Honour

Royal Army Medical Corps

Captain John Cropper, Aged 51, Son of Edward and Theodosia Cropper of Fearnhead, Great Crosby; Husband of Anne Cropper of Mount Ballan, Chepstow, Monmouthshire. Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece.

Serjeant William Sharpe, Aged 39, Son of Elizabeth Norah and the late John Sharpe. Served in the South African Campaign. Buried at Syra New British Cemetery but also Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece

Private Arthur Binks, Buried at Piraeus Naval and Consular Cemetery

Private George James Bostock, Aged 23, Son of William and Elizabeth Bostock of Nottingham. Husband of Ada Bostock of Sneinton Dale, Nottingham. Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece.

Private Henry Freebury, Aged 31. Son of Mrs C Freebury of Clarence Cottages, Misterton; Husband of Miriam Bilton (formerly Freebury) of High Street, Misterton, Doncaster. Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece.

Private Thomas Jones, Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece.

Private George William King, Aged 24, Son of Herbert and Sarah King of 21 Greenbank Avenue, New Brighton, Cheshire. Wounded in France in 1916. Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece.

Private Leonard Smith, Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece.

Private William Stone, Aged 23. Son of Harry and Polly Stone, of 17 Dudley Street, Walsall, Staffs. Husband of Anna Wilks (formerly Stone). Commemorated on the Mikra Memorial, Greece.

Mercantile Marine

Trimmer Robert Charles Babey, Aged 24, Son of the late Robert Charles Babey and of Elizabeth Babey, of Hook Lane, Warsash, Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Fireman Joseph Brown, Aged 41, Buried at Piraeus Naval and Consular Cemetery

Butcher 4th Class Thomas Archibald Crawford, Aged 27. Son of Elizabeth Jane Crawford, of 1 Argo Road, Waterloo, Liverpool, and the late Thomas Archibald Crawford. Born at Higher Tranmere. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Trimmer Arthur Dennis, Aged 20 Son of Arthur and Emily Dennis, of Mansbridge Cottages, Swathling, Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Fireman Frank Jospeh Earley, Aged 47. Son of Catherine and the late William Earley; husband of Mary Ann Earley, of 6 Lower Back of Walls, Southampton. Born at Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

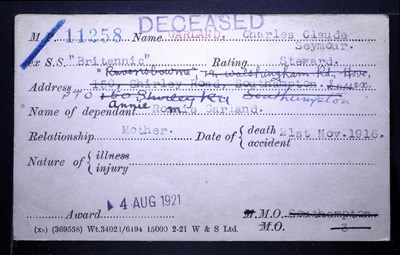

Steward Charles Garland, Aged 33 Son of Annie Romie Garland, of 150 Shirley Road, Southampton, and the late Alfred Garland. Born at Bristol. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Scullion Leonard George, Aged 15, Son of Thomas and Catherine Elizabeth George (nee Groves), of 15 Compton Walk, Southampton. Born at Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

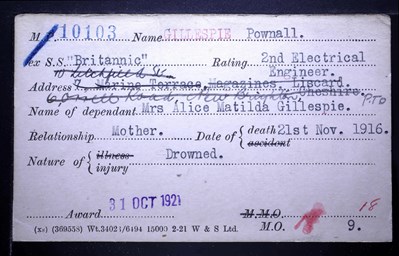

Second Electrician Pownall Gillespie, Aged 34. Son of Alice Matilda Gillespie (nee Griffiths), of 7 Marine Terrace, Liscard, Cheshire, and the late William Gillespie. Born at Liverpool. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Fireman George William Godwin, Aged 28. Son of James and the late Ellen Godwin; husband of Charlotte Dorothy Madeline Godwin (nee Woods), of 90 Belvoir Valley, Southampton. Born in Dorset. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Seaman G Honeycott, Buried at Piraeus Naval and Consular Cemetery

Second Baker Walter Jenkins, Aged 39. Son of the late William and Margaret Jenkins; husband of Edith Jenkins (nee Bates), of 260 Commercial Road, Liverpool. Born at Egremont, Cheshire. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Assistant Cook Thomas McDonald, Aged 24 (Served as TAYLOR). Son of Mary Taylor (formerly McDonald), of 5 Macqueen Street, St. Oswald Street, Liverpool. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Fireman John George McFeat, Aged 27, Son of Jane and the late Mr. McFeat; husband of Ellen Louisa McFeat (nee Lewis), of 19 Bevois Street, Southampton. Born at Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Trimmer Charles Phillips, Aged 23. Buried at Piraeus Naval and Consular Cemetery

Fireman George Bradbury Philps, Aged 41. Son of Harriett and the late Edward Philps; husband of Emily Louisa Philps (nee Rose), of 4 Roman Street, Southampton. Born at Alton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Steward James Patrick Rice, Aged 22, Son of James and Margaret Rice, of 13 Denbigh Street, Bootle, Lancashire. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

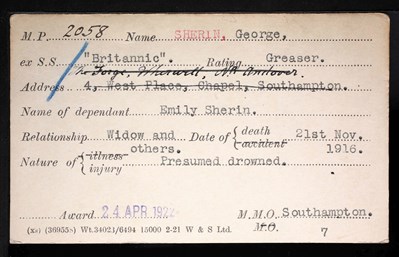

Greaser George Sherin, Aged 42. Son of the late Joseph and Caroline Sherin; husband of Emily Sherin (nee Pearce), of 4 West Place, Chapel Road, Southampton. Born at Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Fireman William Smith, Aged 29. Born in London. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Steward Henry James Toogood, Aged 48. Son of the late James and Henrietta Toogood; husband of Caroline Toogood (formerly Ramsey, nee Davis), of 19 Chantry Road, Southampton. Born at Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

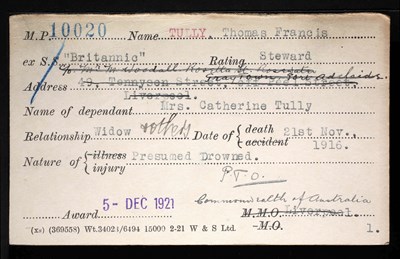

Steward Thomas Francis Tully, Aged 38. Son of the late Mr and Mrs James Tully; husband of Catherine Tully (nee Woodall), of 49 Tennyson Street, Peel Road, Bootle, Lancashire. Born at Roscommon. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

Trimmer Percival White, Aged 18. Son of James Albert and Nellie Elizabeth Mary White, of 28 College Street, St. James, Southampton. Commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial

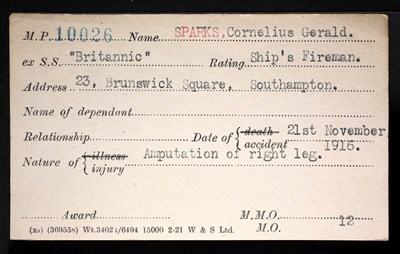

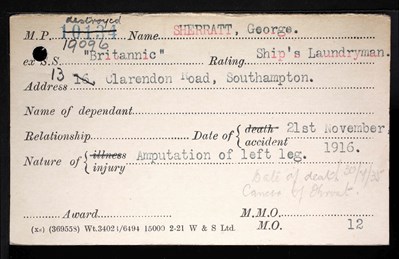

Using the WFA's Pension Record Archive we can find a little more about some of these men

Additionally, the records of some men who survived can be found. Here are just two examples:

Cemeteries and Memorials

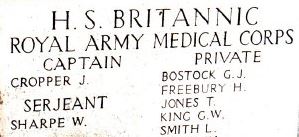

Within Mikra British Cemetery stands The Mikra Memorial which commemorates nearly 500 individuals who died on five ships which were lost in the Mediterranean.

Above: A section of the Mikra Memorial.

This panel of the Mikra Memorial lists men of the RAMC who were lost when the Britannic sank, and who have no known graves.

The Piraeus Naval and Consular Cemetery contains just twenty three First World War burials, the earliest of these being three men lost from the Britannic from the Mercantile Marine and one RAMC private.

The Tower Hill Memorial in London commemorates nearly 36,000 men and women of the Merchant Navy and fishing fleets who died in the two world wars and who have no known grave. Of the total commemorated 12,000 are First World War casualties, including eighteen Mercantile Marine sailors who were lost on the Britannic.

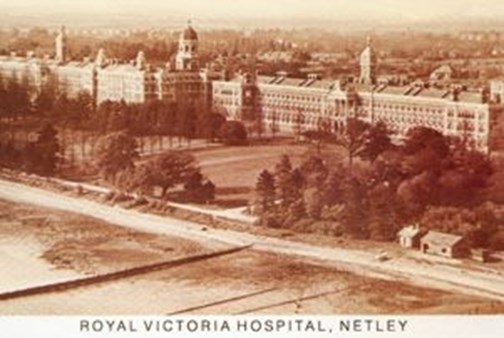

On the outskirts of Southampton stands Netley Military Cemetery which was in the grounds of the Royal Victorian Hospital. It was this hospital that received many of Britannic’s patients who were returned to the UK after her trips to the Eastern Mediterranean.

Part of Netley Military Cemetery. Image courtesy of Hamble Interactive

The Hospital was first used in 1863, and during the war was expanded to accommodate 2,500 patients. Used extensively in the Second World War, it fell into disuse in the 1950’s and was destroyed by fire in 1966, all that now remains is the Chapel

The Hospital chapel, now a visitors centre.

Article by David Tattersfield,

Development Trustee, The Western Front Association