The Munitionette’s First Heavy Shell. The Struggle to produce Munitions 1915 to 1918 by John Hughes-Wilson

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Munitionette’s First Heavy Shell. The Struggle to produce Munitions 1915 to 1918 by John Hughes-Wilson

If, in modern warfare, fuel is the blood of victory, then munitions – in all their varied forms – are the muscles and sinews. This raw truth was first understood as the First World War deteriorated into a crude slogging match dominated by guns, shells, machines and the power of industrial output to support soldiers on the battlefield. The Germans even had a name for it, the Materialschlacht – the battle of production. Britain was ill–prepared.

With the exception of the recent naval arms race, the Treasury’s thinking had always been to deliver the minimal equipment at the cheapest price, and soldiers in 1914–15 paid the price. Part of the problem also lay with the War Office, whose pre–war policy had been to procure light battlefield artillery at the expense of heavy guns. So Britain not only had a shortage of heavy artillery for the siege warfare that evolved in the trenches, but also had no stockpile of ammunition. Worse, there was no manufacturing base to produce shells quickly. It took a crisis, a new Ministry of Munitions (headed by David Lloyd George) and the imposition of state control to turn things around.

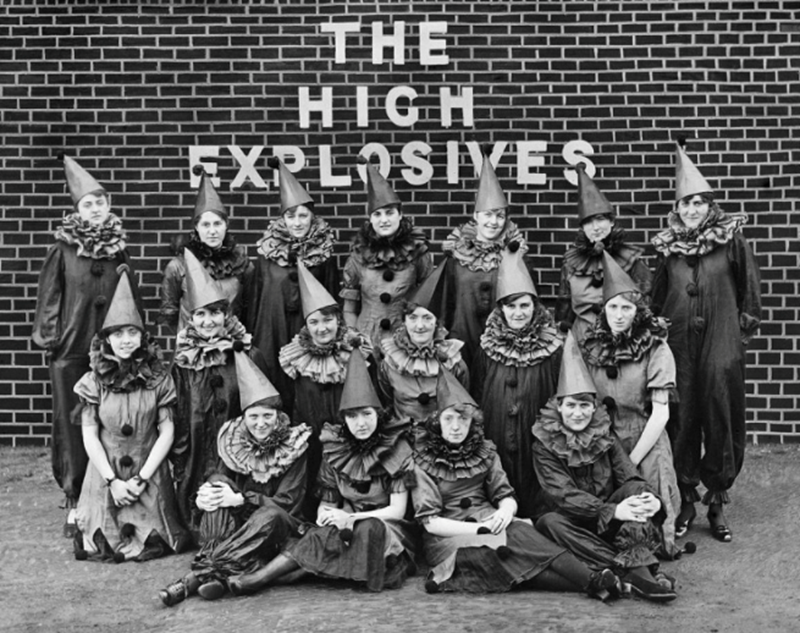

This 8–inch High Explosive shell was the first ever made by women in Britain during the war. As such, it was not sent to be hurled at the enemy but instead preserved for the collections of the Women’s Work Committee at the nascent War Museum. It was manufactured in Liverpool, which, on 4 June 1915, David Lloyd George visited to initiate a regional munitions campaign. Within weeks, shells were being made at two Liverpool Corporation–owned sites. The Cunard Steam Shipping Company, owners of the recently torpedoed Lusitania, also offered a warehouse in Bootle and the building was quickly adapted. Soon, the Cunard National Shell Factory was making 4.5–inch and 6–inch High Explosive shells, and from September the heavier 8–inch shells, too.

Over three–quarters of the 1,000 employees at the factory were women, ‘mostly drawn from middle class homes, and the majority had not previously been engaged in Factory work’ as noted in the factory’s History. They worked all the lathes, and the Cunard factory became the first to make 6–inch and 8–inch shells entirely by female labour. This shell was initially displayed at a temporary exhibition at Burlington House in January 1918 and has remained on show ever since, a testament to the immense national effort made by over 900,000 British women in the munitions industries to keep the guns firing.

In 1914, the War Office’s Army Ordnance Department – which in peacetime had war hasty contracts were issued to the existing domestic arms manufacturers and to American companies. Unfortunately, most of the early ammunition contracts were for shrapnel shells, which had given good service in the open veldt of South Africa but which proved useless for cutting barbed wire effectively or for blowing up enemy dugouts on the Western Front. The War Office ordered millions of them.

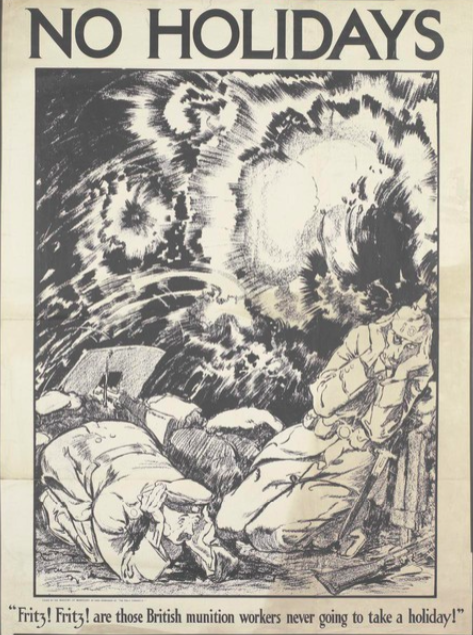

Three key factors now hampered a rapid expansion of the British armaments industry: a shortage of key raw materials, including chemicals; a paucity of the specialist armaments factories, which were already at full capacity; and a fragmented railway distribution network of over a hundred competing companies (which had at least been placed under overall government direction by September 1914). The result was that the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was seriously short of shells in spring 1915. The BEF’s Sir John French was bitter. After the disappointment of Neuve Chapelle on 10 March 1915 and especially the failure at Aubers Ridge on 9 May the same year, French briefed Lieutenant Colonel Charles Repington, military correspondent of the Times, in detail.

He even showed him confidential military documents. The Times described the BEF’s shortage of shells in graphic detail: ‘We had not sufficient high explosives to lower the enemy’s parapets to the ground ... The want of an unlimited supply of high explosives was a fatal bar to our success’. Ironically, the brief hurricane bombardment necessitated by the shell shortage had contributed to the preliminary success of Neuve Chapelle. But it was one thing to make a positive tactical choice, and quite another to be in a position of having no alternative. Thus, a ‘shell scandal’ broke out as an angry public demanded action.

This crisis, compounded by the failure of the Gallipoli landings, effectively brought down Asquith’s Liberal government. David Lloyd George – a vociferous critic of alleged War Office profligacy in peacetime – now berated the Ordnance Department for its dilatoriness and sloth. Under pressure, Asquith formed a new Coalition government, and the War Office lost responsibility for munitions as Lloyd George was appointed to head the new Ministry of Munitions in May 1915. He soon found out the truth. British industry lacked the high–quality modern machine tools and the specialist semi–automatic forging machines needed for shell manufacture, had no chemical industry big enough for the mass manufacture of explosives, and possessed few companies able to manufacture precision fuses. He addressed these with his characteristic energy, helped by the passage of the Munitions of War Act in July 1915, which brought munitions production under state control.

Lloyd George recognised that Britain’s whole economy needed to be geared for war. The state now took over direction, with munitions the key industrial priority. An Imperial Munitions Board was set up to ensure that supplies and factories in Britain and Canada were organised to provide adequate shells and other war material for the duration.

A huge munitions plant, officially named ‘His Majesty’s Factory’, was built near Gretna, on the English–Scottish border outside Carlisle, and by mid–1916 was in production. A large bureaucracy developed to administer the vast state effort. For months to come the shells supplied still reflected orders placed by the old War Office, but during the latter part of 1916 the speed and volume of manufacture was transformed by these changes.

The Ministry of Munitions was staffed by experienced businessmen able to coordinate the needs of big business with those of the state and reach a compromise on price and profit. Government agents bought essential supplies from abroad and then controlled their distribution in order to prevent speculative price rises and profiteering. The government controlled all dealings in metals as well as coal.

All over the country factories were converted to munitions production, and machines and skills were adapted to military use. In Birmingham’s jewellery quarter skilled craftsmen turned to making hand grenades; pen manufacturers found themselves producing cartridge clips.

The efficient production of munitions required a consistent, ample and stable workforce. ‘Treasury agreements’ had been reached with 35 unions, which, among other things, sought to prohibit strikes and lockouts, created means for arbitrating disputes and allowed for the so–called ‘dilution’ of labour – the replacement of ‘skilled men’ who had enlisted with ‘semi–skilled’ or ‘unskilled men’ and (even!) with women. These measures were then incorporated into the Munitions of War Act, along with restrictions on the movement of labour, which made it hard for workers in vital industries to change jobs.

The government’s centralisation of control was thus paralleled in the enhanced status of trades unions and their leaderships, who now carried a raft of responsibilities as partners in the war economy. They were initially opposed to the introduction of women workers, whose wages never reached parity with men’s, but the facts spoke for themselves. By mid–1917, women dominated fuse production, overcoming a backlog of 25 million fuses. But the general shortage of labour also gave unions considerable muscle, as the law of supply and demand drove wages up to unprecedented levels. Skilled machine operators could command £3 and 10 shillings a week at a time when a private soldier’s basic pay was 7 shillings a week. Unsurprisingly, trades union membership doubled during the war, reaching 4.5 million in 1918.

Rising food prices, rising rents and other factors provided reasons for disgruntlement and fuel for militancy, and (the laws notwithstanding) Britain lost 27 million days in strikes – more than four times the number in Germany. By the end of the war, though, it was clear that the overriding need for munitions had been met. At war’s end, the Ministry of Munitions had a staff nationwide of 65,000, employing some 3 million workers in over 20,000 factories, including 250 government controlled ones (143 of them state–owned).

In 1914, British factories produced 300 machine guns; in 1918, they made over 120,000. In 1917, the 76 million shells produced that year was over 150 times the quantity made in 1914. And by the end, many thousands of the new war machines – tanks and aircraft – had rolled off the production lines. As the Germans ruefully acknowledged, they had lost the Materialschlacht.

This article first appeared in Stand To! No.100 June 2014 Centenary Edition as part of the series ‘The First World War in 100 Objects’ by John Hughes-Wilson. The entire digital archive of Stand To! is available to Western Front Association members via your member login. Additional photographs from the Imperial War Museum and Historic England Archives have been added.

Interesting Links :

BBC World War One at Home. Cunard Shell Works, Merseyside. Pioneering Womens’ Wartime Work.