The Original Long Distance Bombers of the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Original Long Distance Bombers of the First World War

Most of us are familiar with the RAF bombing campaigns of the Second World War, but few are aware that such cities as Cologne, Frankfurt, Mannheim and Stuttgart had already been targeted two decades earlier during the First World War.

The reward for building an organisation like The Western Front Association on a foundation of reputable research is that it attracts items like the one that appeared on ‘The Independent Force’ in the Bulletin of June 1999 byAndrew Whitmarsh of the RAF Museum, Hendon.

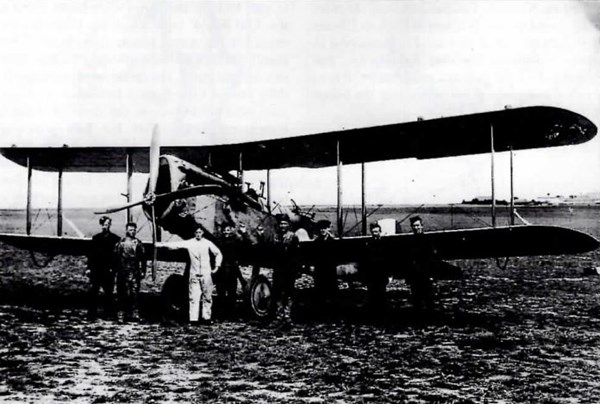

Above: A De Havilland DH4 with ground crew which was part of the Independent Force day bombing squadron. (picture courtesy of the RAF Museum)

What follows is an abridged version of the article…

'Strategic bombing, which at the time of the Great War was generally known as long distance bombing, seeks to engage the enemy away from the battlefield - for example by attacking his means of military production or the morale of his citizens. It is therefore independent of Army and Navy operations, hence the origin of the name the ‘Independent Force’.

'The dropping of projectiles and explosives from flying machines had been prohibited by as early as 1899 at the Hague Convention. Once the Great War had begun, it was the Germans who initially made most use of strategic bombing, with attacks on Great Britain first from Zeppelin airships and later from Gotha aircraft. These attacks caused considerable panic, and sometimes serious casualties: the Gotha raid of 13th June 1917 killed and wounded 594 Londoners.'

Above: Deadly Zeppelin attacks on London pushed the political will for counter-attacks.

“It was five months after this attack that Admiral Mark Kerr of the Air Board warned that,‘…the country who first strikes with its big bombing squadrons of hundreds of machines at the enemy's vital spots, will win the war’.

“It was in this kind of atmosphere that, in the second half of 1917, plans were drawn up for making British bombing raids into Germany. This was not to be the first sustained British strategic bombing campaign of the war: in co-operation with the French, from October 1916, the bombers of 3 Wing of the Royal Naval Air Service had begun making raids against German cities. These operations were opposed by the Royal Flying Corps and War Office, who believed that the aircraft could be put to better use in direct support of British troops, and in April 1917 they were withdrawn.

“The Zeppelin and Gotha raids on the United Kingdom placed increasing political pressure on the military to strike back. In October 1917 therefore, 41 Wing RFC was set up to bomb Germany from the Nancy region.”

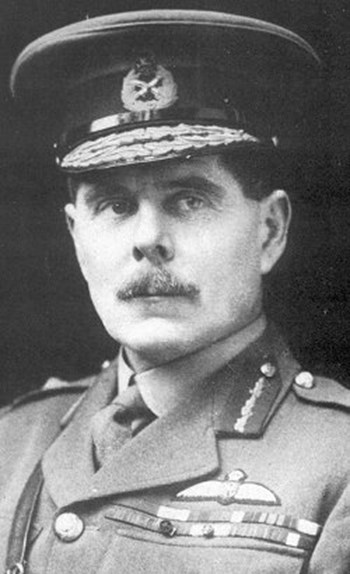

Later renamed 8 Brigade, from June 1918 until the end of the war it was known as the Independent Force or Independent Air Force and would expand from three squadrons to nine. One reason for its renaming was the appointment on 6th June 1918 of its new commander, Major General Sir Hugh Trenchard, who had been commander of the RFC in France for most of the war and was now operating with a freer remit. Never a great advocate of long-distance bombing, he would record in his diary that he thought the process was being driven by politicians.

Above: Major General Sir Hugh Trenchard

“Despite the urgency surrounding the formation of this bombing force at the end of 1917, there was some confusion as to exactly what it should do. Opinions varied among politicians, Air Ministry planners and the airmen themselves. Some, including the Air Ministry planners, argued that the German war effort could be crippled by bombing a small number of key German industrial facilities. At the opposite extreme, others (including Trenchard) believed that the physical damage caused by British bombs was less important than the strain attacks inflicted on German morale and efficiency.

“During Trenchard's first month in command, the Independent Force dropped less than one quarter of its bombs on the primary and secondary targets (chemical factories and iron/steel works) allocated by the Air Ministry. Over the whole of its period of operations, the majority of bombs were dropped on targets which were not approved by the Air Ministry.”

Above: An FE2b of 100 Squadron ready for a night raid. (picture courtesy of the RAF Museum)

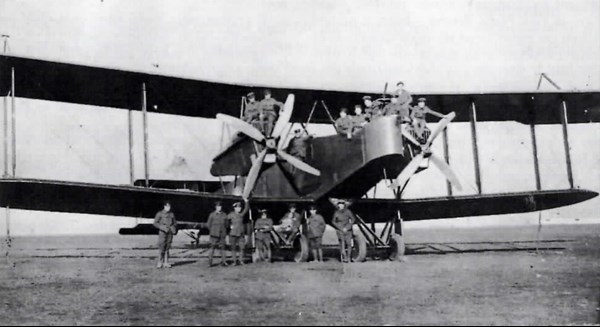

Above: Airmen of 216 Squadron with a Handley Page 0/400 night bomber in 1917. (picture courtesy of the RAF Museum)

A variety of aircraft were used, with the main requirement for night bombers being their flight range and ability to carry a weight of incendiaries. In the case of day bombers, they needed to be better equipped to defend themselves against enemy fighters. The night bombers operated individually, with the main danger coming from anti-aircraft guns aided by searchlights and networks of barrage balloons, whilst the daytime bombers flew in formations.

'Initially the obsolete FE2b was used at night, but the main night bomber of the war was the Handley Page 0/400, which had three crew and could spend eight hours in the air. Yet even this could carry only one-seventh of the bombload of a Second World War Avro Lancaster bomber.'

By the end of the war, the 0/400 was in service with five Independent Force squadrons and the other four used two-seater de Havilland day bombers.

Above: A German anti-aircraft team prepares for action.

Venturing far over enemy lines there was little chance of nursing an aircraft home if a problem occurred, and casualties were heavy - especially amongst day bombing squadrons. In September 1918, for example, 75 per cent of the force’s 122 aircraft were lost or inoperable.

'In addition to the hazards of enemy action, aircrew also had their environment to contend with. Despite being provided with heated clothing and rudimentary oxygen apparatus, the crew often suffered from the cold and from oxygen deprivation due to the height at which they flew. The lighter bombs sometimes compacted rather than exploding if they hit a solid structure; navigational instruments were unreliable; bombsights were ineffective; and bombs were often dropped purely by estimation -from altitudes of 14,000 feet or more!

'Targets were identified courtesy of intelligence obtained from behind German lines, such as newspapers, enemy prisoners of war or deserters, repatriated Allied prisoners, and Allied agents. After the war, RAF inspectors visited bombed towns to measure the success of the campaign. The inspectors found that British bombs had frequently missed intended targets. Yet even if little damage was caused directly to the enemy war industry, the bombing impeded it in other ways. The Germans constructed an expensive defence network: such as fighter aircraft, anti-aircraft guns and searchlights in addition to an air-raid detection system, dummy factories, shelters for workers and so on. The psychological strain and delays to factory production due to alerts could be considerable.

'German casualties caused by Independent Force raids are not known for certain. However, the Independent Force should not be dismissed as insignificant - had the war continued into 1919, it would have been joined by French, Italian and American bombing squadrons as well as fighter escort squadrons. Even after 11th November 1918, two V/1500s stood ready to conduct ‘special demonstrations’ over Berlin in case the Germans abandoned the Armistice.'

Original research Andrew Whitmarsh. Edited Dr Martin Purdy