The Quest for Grandad’s photo: Pte James Cooper, 1st. Bn. Essex Regiment

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Quest for Grandad’s photo: Pte James Cooper, 1st. Bn. Essex Regiment

'The grassy slopes that crown the cliffs are carpeted with flowers. The azure sky is cloudless and the air is fragrant with the scent of wild thyme. In front, a smiling valley studded with cypress and olive and patches of young corn, the ground rises gently to the village of Krithia standing amidst clumps of mulberry and oak. On the left, a mile out into the Aegean, a few warships lie motionless, like giants asleep, their gaunt outlines mirrored in a satin sea: while behind them, in the tender haze of the horizon, is the delicately pencilled outline of snow-capped Samothrace. Only high on the shoulder of Achi Baba – the goal of the British troops – a field of scarlet poppies intrudes a restless note. Yet in half an hour that peaceful landscape will again be overrun by waves of flashing bayonets, and these are the last moments of hundreds of precious lives.'

Captain Cecil Aspinall.

Until the last sentence Capt. Aspinall describes a lyrical scene worthy of recording in a photograph. With current technology, it is difficult to imagine a time when families did not own a camera. Often the only link we have to those who served in the Great War is a faded photograph, taken individually or with a group of fellow conscripts proudly wearing their new uniforms. These were commonly taken in a photographers' studio, rather stiffly posed in front of a backcloth, to be treasured as a keepsake by the soldier’s family. Although the Vest Pocket Kodak (VPK) camera was developed in 1912 and helped popularise the taking of pictures by private individuals, at £1.10s.0d. the VPK was still often beyond the means of working class families. Many cameras found their way to theatres of war, but by mid-1915 the War Office prohibited anything other than ‘official’ recording of the conflict.

Documents for this article were shared with the author by James Cooper’s family, in the hope of finding a photo of Grandad. A picture of him has not been traced to date, despite an extensive search in records for his brief army service, and many other sources. Ian Hook, curator of the Essex Regiment Museum for over 28 years, summed up the situation succinctly, 'some regiments were manned by poets and photographers, but the Essex Regiment was not one of these.'

James was born in Bocking, Essex in 1877, the son of Samuel and Hannah Cooper who owned a store in Manor Street, Braintree. Further along the same street was the school James attended, which now houses Braintree Museum. In 1900 he married Alice Willis and by the 1911 Census he was earning a living as a carpenter. Unfortunately no Attestation papers survive, but two family history sites show his place of enlistment as Camberwell, presumably at the Town Hall. As that was some distance from James’ home at Leigh on Sea, Essex, it has always been assumed that he was journeying to wherever work was available, as he had four young children to support by 1914.

After Lord Kitchener’s appeal for men to join up when three quarters of a million volunteered, it was not until the Military Service Act of May 1916 that terms were extended to include married men.

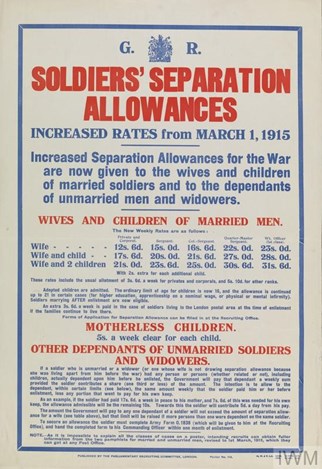

Above: Poster of Soldier’s Separation Allowances. (IWM)

The poster may have influenced James’ decision to enlist, while others looked on it as something of an adventure and a chance to escape from everyday life. Whether through patriotism, or a spur of the moment impulse, we will never know why James signed up. The allowances may have made life temporarily easier for Alice Cooper and her children, but the situation changed dramatically in August 1915.

After passing the regulation tests, James was posted to the 3 Special Reserve of the Essex Regiment for basic training lasting three months. The Reserve was formerly part of a Militia unit which was mobilised at the outbreak of war to supply men to the Regular battalions. 1 Battalion, Essex Regiment had been stationed in Mauritius and only returned to the UK in December 1914. By January 1915 they moved to Oxfordshire for two months further training. Banbury Museum has a copy of Kevin Northover’s book which gives an account of the regiment there, unfortunately with no photographs.

“The first to arrive in Banbury were the 1 Battalion of the Essex Regiment. They had returned home to England in December and detrained at the L&NWR railway station in Banbury on the afternoon of Monday January 18, 1915. The soldiers were greeted by a large crowd and flags were hung from business premises and private houses along the route to the town. This large column was taken through the town by the Territorial Band to the Horsefair, where they were dispersed and led to their billets by Scouts … most of the men were billeted in the centre of the town … a second train of troops arrived later … the battalion consisted of 899 men and 25 officers and their headquarters were established at the Drill Hall, Crouch Street. During their short stay in the town the Regiments (also 4 Battalion Worcestershires) continued training in the countryside around Banbury and were generally very popular with the locals, and many romances and friendships were formed with the men. They departed from the town on Friday 4 March. When the Gallipoli operation began and the casualty lists appeared in the Banbury Guardian they had a special tragic significance for the people of Banbury.”

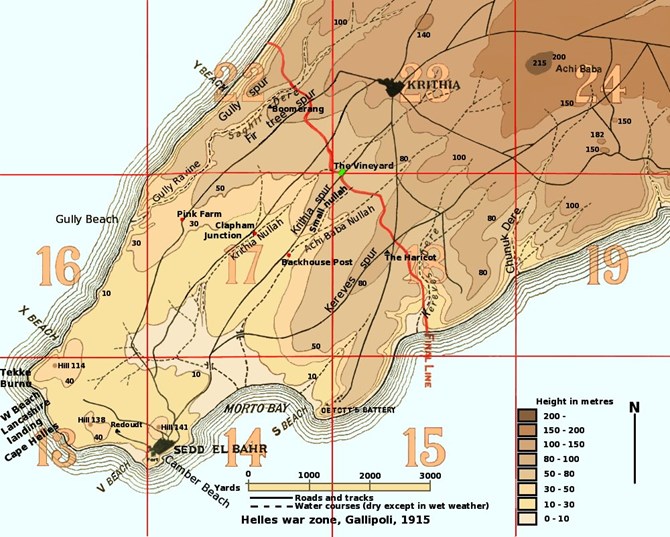

Above: Map of Helles area actions, 1915

By March 21, 1915 the 1 Bn. Essex which were part of 88 Brigade, 29 Division, and known as the Incomparable Division, were ordered to “Take no action in the Dardanelles until 29 Division arrives.” Initially under the command of Maj-Gen Aylmer Hunter-Weston, it fought throughout the Gallipoli Campaign, sustaining around 34,000 casualties there , with 12 Victoria Crosses awarded. As part of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force it made the first landing on the Peninsula in April 1915, and did not leave until January 1916.

Above: 1/Essex landing on W Beach.

From the time 1 Essex established their positions at the end of April, the War Diary shows a constant war of attrition taking place daily with attack and counter attack. Ground was lost and then regained, despite poor artillery cover and inadequate communications. Heavy bombardment by Naval guns were not always effective in helping prevent costly and futile attacks resulting only in deadlock. In Arthur Behrend’s book Make Me A Soldier, an artillery observation officer reveals that 'my battery is horribly short of shells.' Artillery in general was in short supply at Gallipoli, especially howitzers, which may have given more positive results as their high trajectory was ideal for the terrain. He paints a different portrait of operational catering involving some Essex officers, clearly not suffering from the ubiquitous fly covered food. 'A case of luxuries from Fortnum & Mason had just been sent up from the Essex mess. Fat Portuguese sardines lying lusciously in pure olive oil were supported by tins of Irish butter and of Devonshire cream.' Chicken in aspic was also included, but the meal was cut short by our Navy bombarding Turkish trenches one hundred yards away from their dugout. They were showered with bits of tree, trench and Turk which possibly curbed everyone’s appetite.

Combinations of daily shell fire, machine guns and snipers caused many casualties, and no matter how many repairs were made, cables reburied and new saps dug, the Essex men faced a relentless onslaught. Lt. John Hughes Allen (1 Essex) wrote a letter home saying,

'The Turks did not reach us and failed to take our trench, however they entrenched themselves not far from us. I thought we should counter-charge them. If we had done it early I believe we should have driven them out, but as the afternoon waned the men became utterly exhausted. You see, they have had an unexampled strain. In France you have two days in the trenches and then a relief; our men had been here for twelve, and for the last three days we have been digging or fighting continuously. The rifle fire of the enemy is worse than in France; the shell-fire not so bad, and we have nothing like the comforts they have there – no parcels or letters or unshelled bases to retire to. We have no sleep to speak of, and our men are utterly done up/'

By the end of May 1 Essex had dug new trenches eastward, up to and including Fir Tree Wood, which they occupied alongside the 5 Royal Scots. Torrential rain added misery to the scene and caused widespread flooding along the line, but the Essex men were relieved on 30 May and went into reserve.

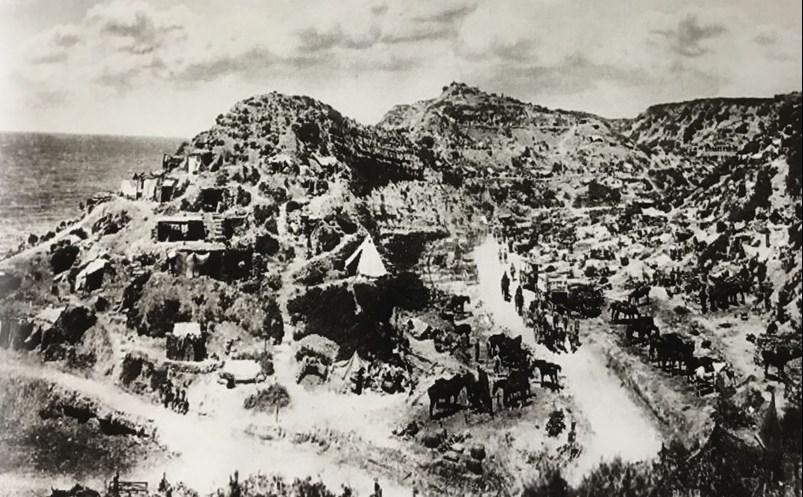

The assimilation scheme saw three companies of Inniskilling Fusiliers reinforcing the line held by 1 Essex when they returned to front line duties in early June. The advance trenches had suffered heavily from enfilading machine gun fire, and the Turks were seen extending trenches they had retaken in front of Krithia. On 9 June the battalion retired to Gully Beach for a rest, digging themselves into the cliffs for cover. (War Diary notes a draft of 5 officers and 236 other ranks joined at this stage.)

Above: Gully Beach and ravine.

After two days at rest, 1 Essex relieved 4 Royal Scots Fusiliers in a move which took over six hours to complete due to blocked communication trenches. On June 15 the enemy were reported to be moving at night towards the Essex held part of the line, and a determined attack followed, but was repulsed. For the next ten days the War Diary reveals nothing of note, with men engaged on improving communications and digging fatigues. On 28 June 1 Essex were ordered to move into fire and support trenches to cooperate with the 1/5 Royal Scots in assaulting position H.12. Considerable delays were caused by blocked trenches, and communication lines holding the wounded, mixed with men of 156 Brigade coming back. Any alternative routes were found impassable due to accurate enemy snipers. Two more attempts were made with the loss of four officers and seventy two other ranks killed or wounded. There was just 300 yards between the lines.

July proved to be a quieter month for 1 Essex with a two week’s rest on the island of Lemnos. They returned to Gully Beach on 28 July, but unfortunately the War Diary pages up to 6 August are completely missing.

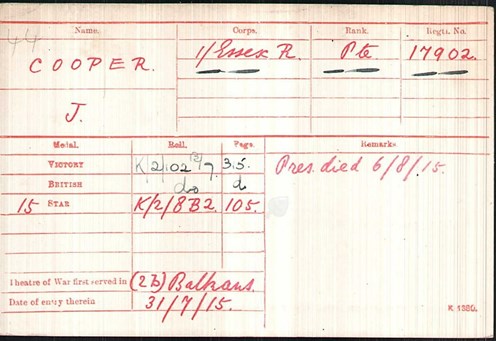

Above: James Cooper's Medal Index card

The Medal Index card shows an entry date into the Balkans’ theatre of operations as 31/07/1915. The only mention of any new additions to the battalion post departure from the U.K. in March 1915, are the 236 other ranks’ arrival on 9 June. As only officer additions are noted individually by name, we will never be sure when James Cooper arrived. It seems that he was only present for one week before he died if the medal card date is accurate. Another possibility is that he came out from England with the June draft, but was sick, and remained on Lemnos for treatment.

The 88 Brigade consisting of the Worcesters, Hants, and Essex with Royal Scots in reserve, were ordered to carry out a diversionary holding attack towards Krithia, over a front of over one thousand yards. 1 Essex War Diary gives the following account:-

'6 Aug. 2:30pm. The bombardment of enemy trenches commenced with heavy artillery being followed later by the Field Artillery which increased to intensity. 3:30pm. At the same moment that our Artillery commenced the bombardment the Turks commenced shelling our trenches with shrapnel, causing a certain number of casualties. They also shelled reserve trenches with High Explosive and Shrapnel. 3:50pm. The Infantry advanced, the Turks at once pouring in heavy shrapnel fire as they got out of the trenches. The battalion advanced in two lines, W Coy. on left. Z in centre. Y on right. X Coy. in reserve. Companies finding their own Supports.

The first trench was taken with little difficulty, then they came under very heavy rifle fire, and were still under heavy shrapnel fire. The Companies were now so weak that, on the Turks’ counter-attacking with bombs and bayonets, they were too weak to hold the captured trenches and were driven back.

Part of X Company were sent to reinforce and a small portion of captured trench was held by W Company during the night under Capt. Bowen assisted by some details of other companies. This was a very difficult position, being exposed on three sides to the enemy’s fire. At daybreak the battalion was withdrawn from the trenches and moved to Gully Beach. Casualties were very heavy. Officers killed 6, missing 8. Other ranks killed 44, wounded 202, missing 173.'

After possibly his first and only experience of action, James Cooper was posted as missing when a roll call was taken on Gully Beach the following day

Although the battle for Krithia Vineyard was over, a different type of struggle began for Alice Cooper and her family of five. Her youngest son had been born in March 1915, and the eldest child was only thirteen. According to Royal Army Pay Corps instructions regarding soldiers missing in action, a period of some months would elapse so that appropriate enquiries could be made before a formal presumption of death. For ordinary families, the loss of army pay made their financial situation more precarious.

Army Council Instruction 17 states, 'The general rule is that pay should be credited up to the actual date of death where this is definitely ascertained, but where that date is not known pay can only be credited to a date four weeks after that on which the next of kin was notified that the soldier was missing. The guiding principle is that a man is entitled to pay while he is alive and no longer.'

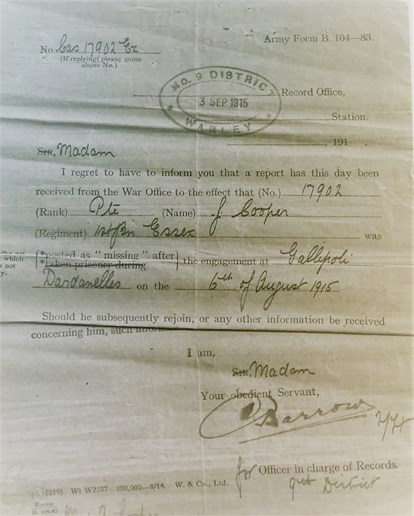

The first information received by Alice was dated 3 September 1915, from Essex Regiment Records, advising that her husband had been posted as missing on 6 August 1915.

Above: Army Form B.104-83 of 3/9/1915

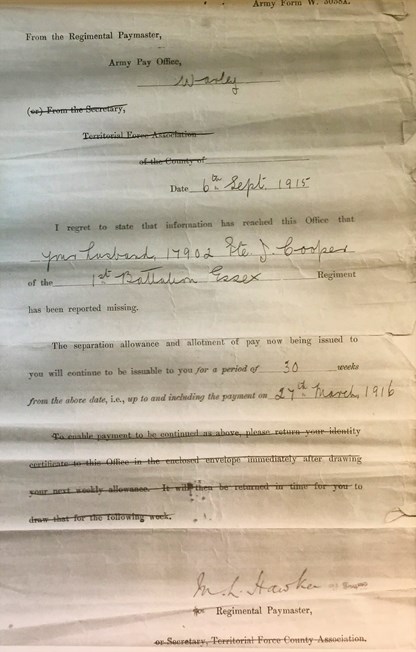

On 6 September a form from the Army Pay Office was sent to Alice advising she would still receive a separation allowance for thirty weeks until 27 March 1916. This allowed further time for enquiries to be made about a man who was missing, before the allowance was turned into a widow’s pension.

Above: Army Pay Office form W.3038A of 6/9/1915

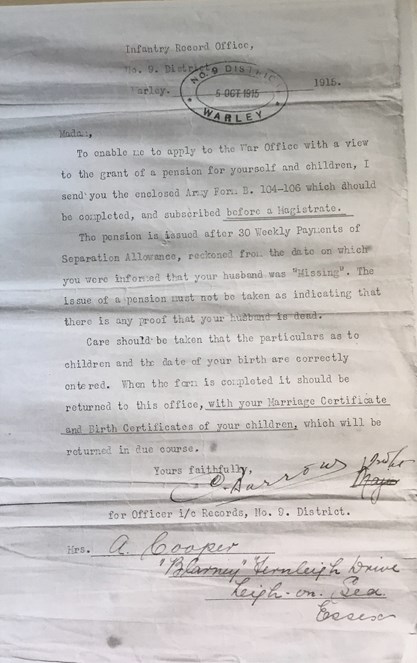

The sheer number of forms issued by various Army departments for just one soldier must have overwhelmed many next of kin, especially those with literacy issues. However, Alice was clearly able to deal with the documents and requests for marriage and birth certificates in a timely manner, and not discouraged by the process.

Above: Letter accompanying Army Form B.104-106 Request for a Pension.

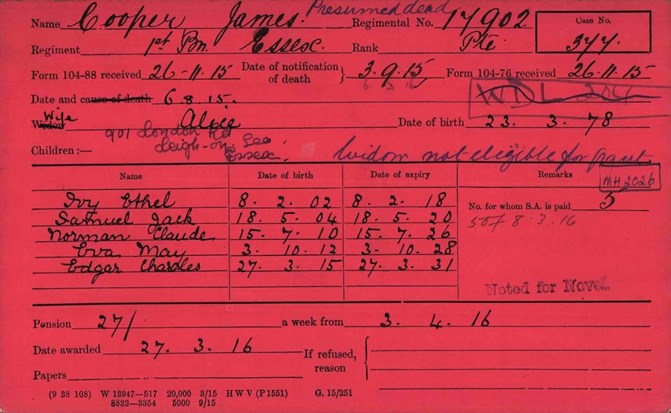

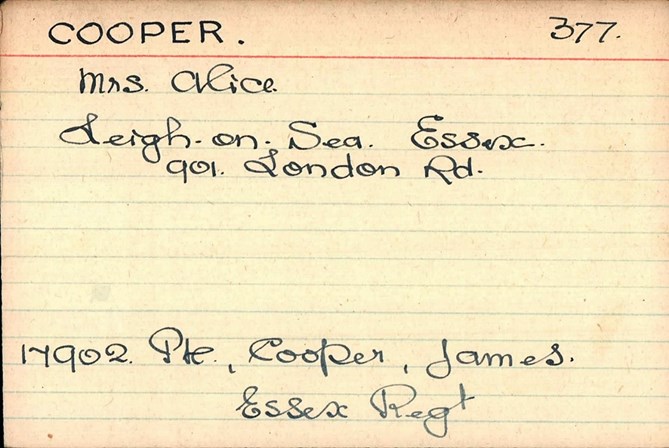

James Cooper now became case number 377 for Pension purposes, but remained Casualty 17902 Essex for Army Records. The red index card, used for dependents of men who were missing, shows ‘presumed dead’ at the top, and widow scored out with ‘wife’ by her name. A payment of twenty seven shillings per week was authorised with effect from 3 April 1916.

Above: Pension card and index card

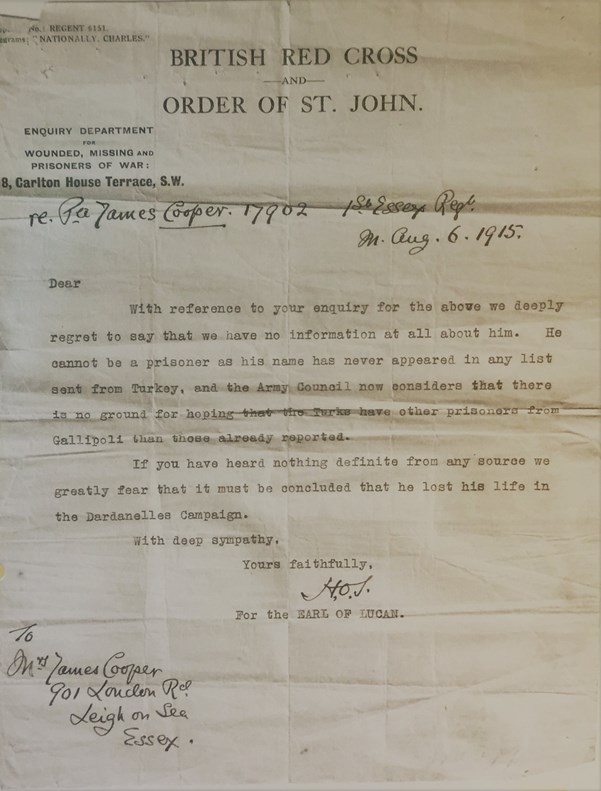

We have evidence that Alice Cooper wrote on two further occasions to the Essex Regiment Records office. She was informed in April 1916 that no further news had been received so therefore James had to remain on the Missing List. In November 1916 the Army suggested contacting the British Red Cross Society. Their response is shown in the image below, and concludes that he was unlikely to be a prisoner of war over a year on.

Above: British Red Cross Society letter.

Andrea Hetherington’s book ‘British Widows of the First World War’ highlights in particular the issues faced by those who had received the B104-83 Army notification that their husband was considered Missing.

'The letter to wives of missing men twenty six weeks after their disappearance, turning their separation allowance into a widow’s pension, was equally ambiguous, stating that the change of payment ‘must not be taken as indicating that there is any proof of the death of your husband’. Not only did this encourage families to believe the prisoner of war dream, but it also encouraged them to seek information through ‘unofficial’ channels, leaving them open to misinformation and fraudsters.'

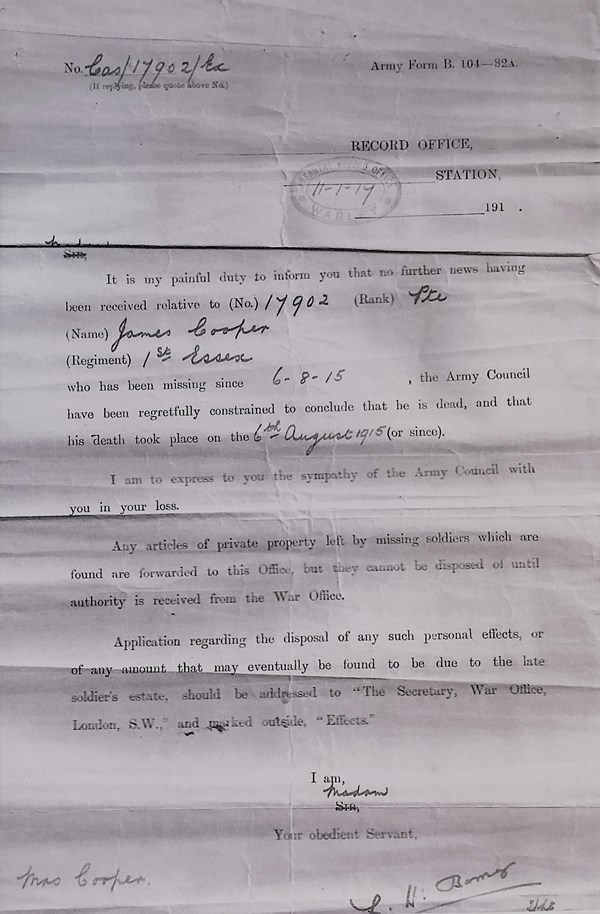

In January 1917 a letter declared James Cooper officially dead, bringing an end to seventeen months of uncertainty.

Above: Notification James now regarded as dead.

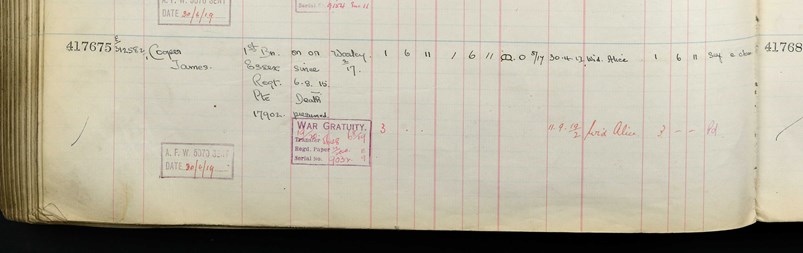

Above: Soldier’s Effects register entry

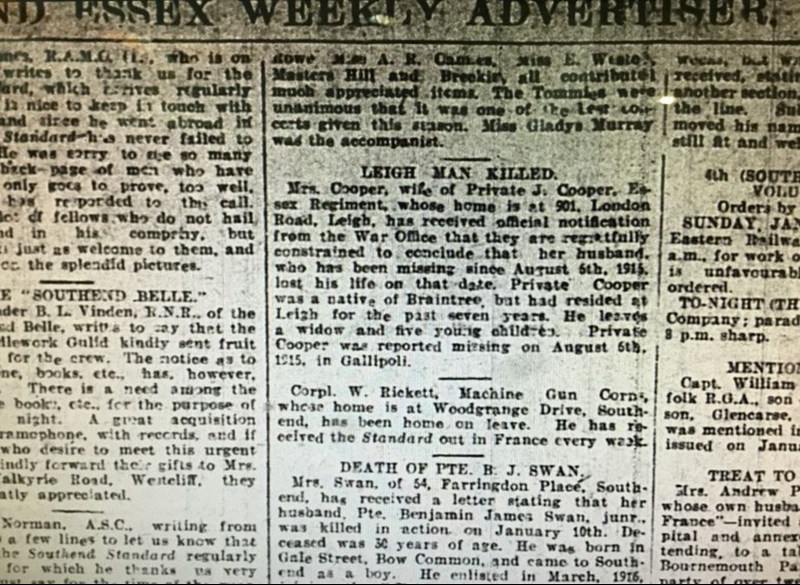

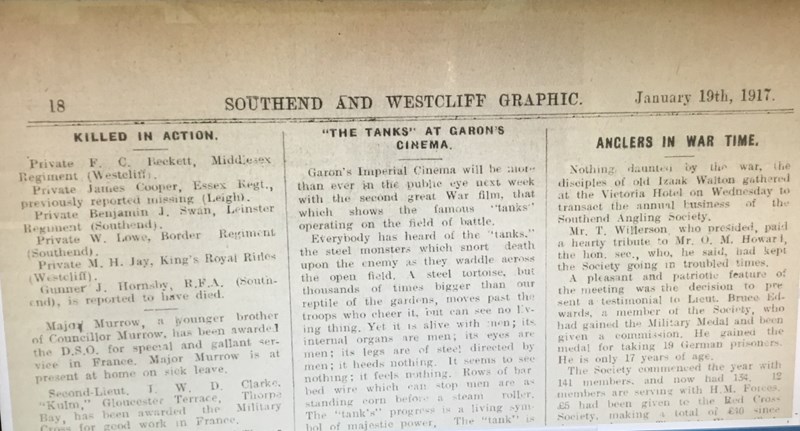

On the 18 January 1917 an Effects form 100c. was issued by the War Office, and the Register showed a sum of £1.6s.11d. was due to the family. Additionally, two local newspapers, the Essex Weekly Advertiser and the Southend & Westcliff Graphic of 19 January 1917, now listed James in obituaries but with no photograph. As it was common for notifications to show a picture, this would seem to confirm that the family did not have one to use.

Above: Local paper obituaries

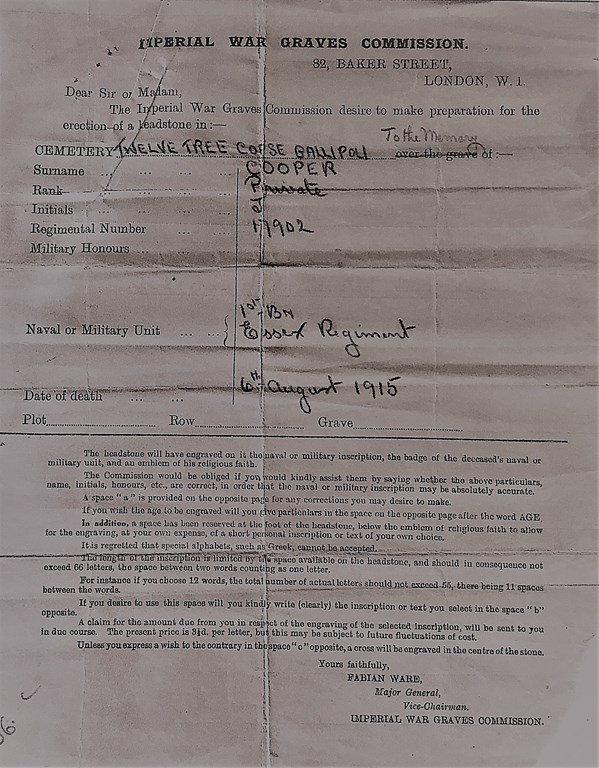

Above: IWGC letter regarding memorial stone.

With five children to raise Alice Cooper was not able to do full time work but did take in washing to earn money. Like many other women of that time she had to bear the responsibility alone, and never remarried. Looking at the documents over one hundred years later still brings home the sense of loss the family experienced. James’s second eldest son recalled he was in bed when he last saw his father, who gave him a small bag of aniseed balls and said “ "Goodbye, son, I'm off to fight in the war".

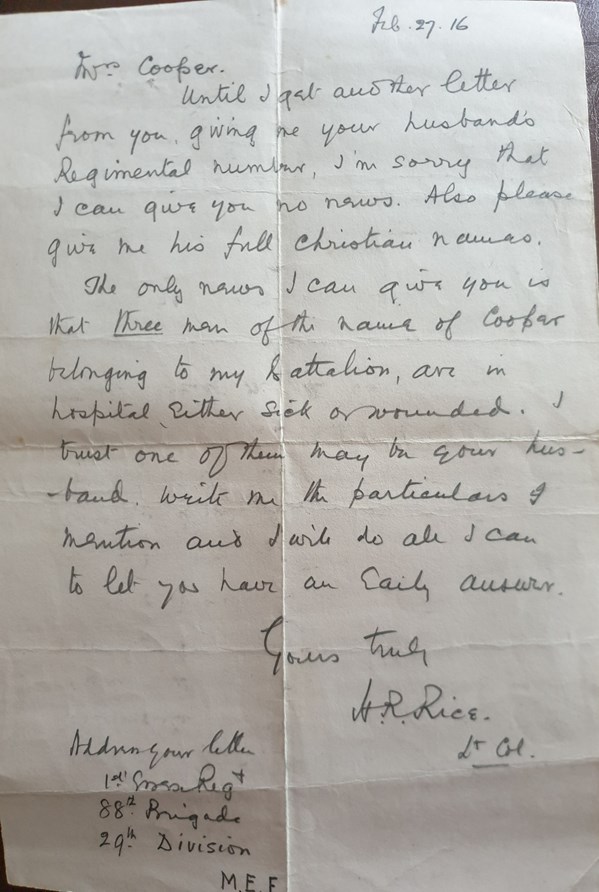

Dissatisfied with replies from the Army concerning information about her husband, Alice wrote to Lt. Col H Rice, 1Essex CO at Gallipoli. He gave a kindly reply asking for more details, promising an early response. He had three men in his battalion with the surname Cooper who were in hospital, and hoped one might have been James.

Above: Lt. Col Rice's letter

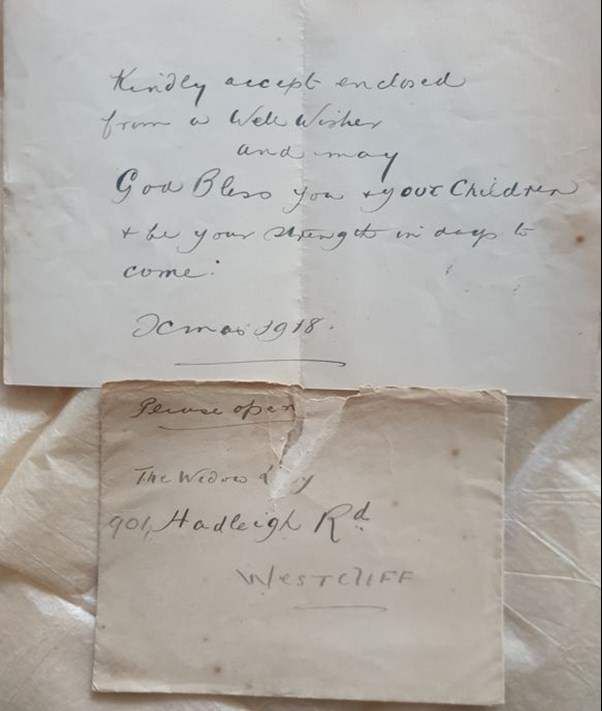

Christmas time must have been particularly stressful, with a fixed income and little money for presents. In December 1918 an envelope was pushed through the letterbox by a well-wisher. The donor was never discovered, but must have been someone who lived close by and knew of the widow and her five children.

Above: Anonymous letter and envelope Christmas 1918.

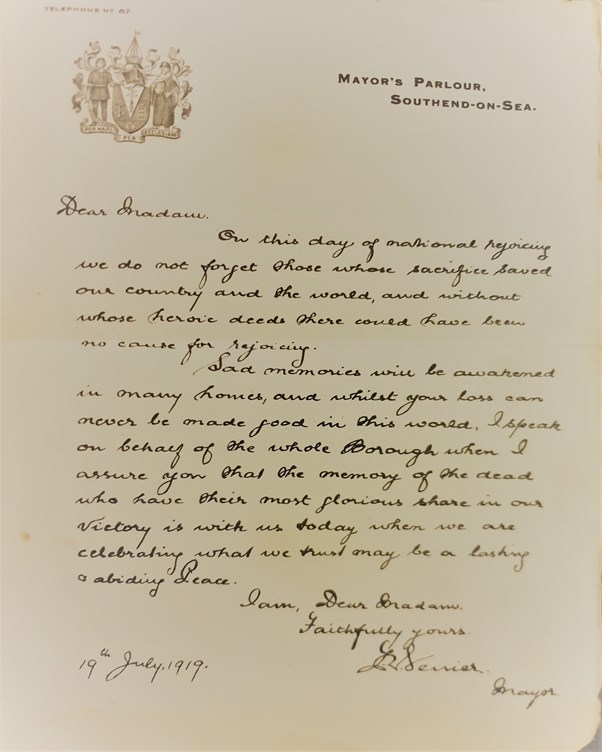

The final document that Alice Cooper kept was a letter from the Mayor of Southend-on-Sea sent in July 1919. While Victory celebrations were being held in many countries it was acknowledged that not all residents had cause for rejoicing.

Above: Mayor’s letter July 1919

None of James Cooper’s family have ever travelled to Gallipoli to see where he died and is commemorated in Twelve Tree Copse CWGC cemetery.

'The Cemetery was made after the Armistice when graves were brought in from isolated sites and small burial grounds on the battlefields of April-August 1915 and December 1915.

There are now 3,360 First World War servicemen buried or commemorated in the cemetery including 141 officers and men of the 1 Essex who died on 6 August 1915.'

Above: James Cooper’s memorial stone B16

Three years ago The Western Front Association Essex branch visited the cemetery during a battlefield tour, and kindly placed the poppy cross by his memorial stone. Despite a great deal of help and advice from other WFA members, online sites, authors, museums, photo archives, county records offices, to date no photograph of Grandad has been found. In the knowledge that unknown Great War documents are still being discovered, pictures of 1 Essex soldiers may still come to light. The search continues.

Article by Dora Ringland