The Real Winslow Boy

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Real Winslow Boy

In 1946, Terence Rattigan wrote the play ‘The Winslow Boy’ – a story of a father’s fight to clear his son’s name of a charge of stealing a 5 shilling postal order whilst a cadet at the Royal Naval College at Osborne. It would later become a film in 1999.

Above: the first edition of the play, published by Hamish Hamilton and a publicity poster for the 1999 film.

The events were far from fiction, however, as they broadly mirrored the circumstances of that of George Archer-Shee, who had been accused of a similar offence in 1908.

George Archer-Shee was born on 6 May 1895, the son of Martin Archer-Shee and his wife, Helen. His father was George attended Stonyhurst College in Lancashire before becoming a cadet at the Naval College at Osborne on the Isle of Wight in January 1908.

Above: The Stable Block at Osborne House, the main building of the former College

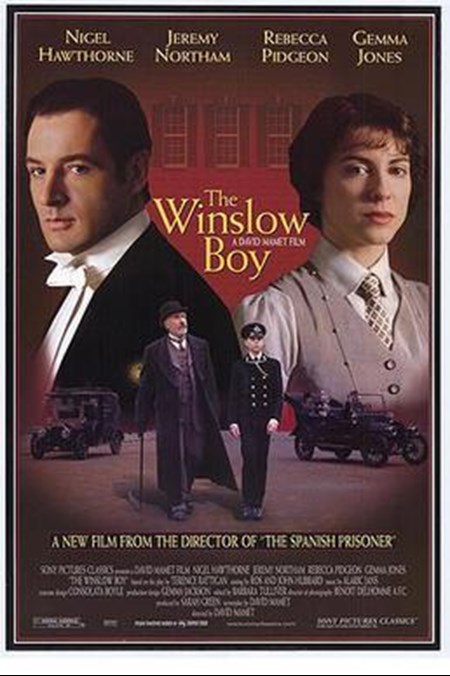

Above: George Archer-Shee as a Naval Cadet, pictured with his father.

But by October 1908, George would be dismissed from the college on the grounds that he had stolen and cashed a postal order from another Cadet – Terence H. Back. George had indeed visited the post office that day to purchase a postal order for 15 shillings and sixpence. The postmistress said only two cadets had come in that day and she was adamant that the boy who purchased the postal order also cashed the postal order for 5 shillings.

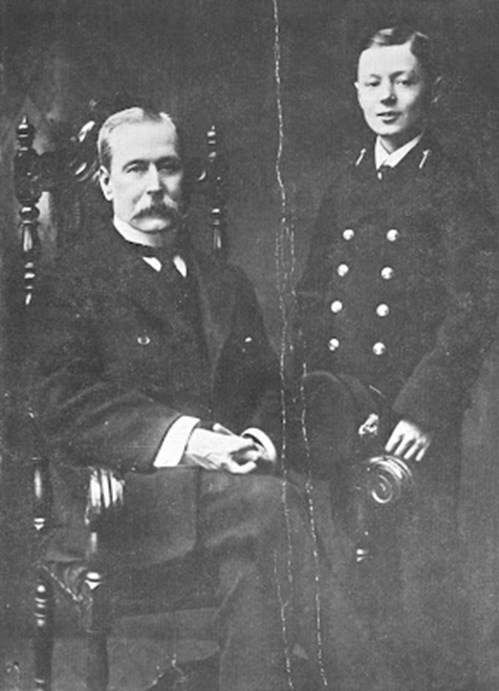

George vehemently denied the accusation but within a matter of days he was dismissed from the college. His father, hitherto unaware of these events, received a letter to this effect and immediately withdrew George from the college. George returned to Stonyhurst College to complete his education.

Above: the text of the letter sent to George’s father. Daily Mirror – 27 July 1910

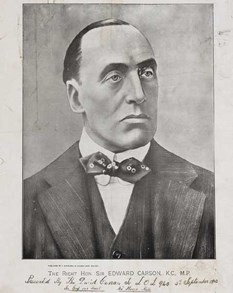

His father refused to believe that his son was guilty of the allegation. His response to the Admiralty’s letter was to indicate ‘Nothing can make me believe him guilty of this charge’. George’s half-brother, Major Martin Archer-Shee, was also firmly in support of George. Martin became the Member of Parliament for the constituency of Finsbury in February 1910, having retired from the Army some years earlier. He would play an important role in obtaining the services of Sir Edward Carson in a Petition of Rights case (Archer-Shee v The King) in July 1910.The Crown was represented by the Solicitor-General, Sir Isaac Rufus.

Above: Major Martin Archer-Shee MP, George’s half- brother, pictured in the Daily Mirror on 9 March 1910.

Above: Sir Edward Carson and Sir Rufus Isaacs, later Lord Reading.

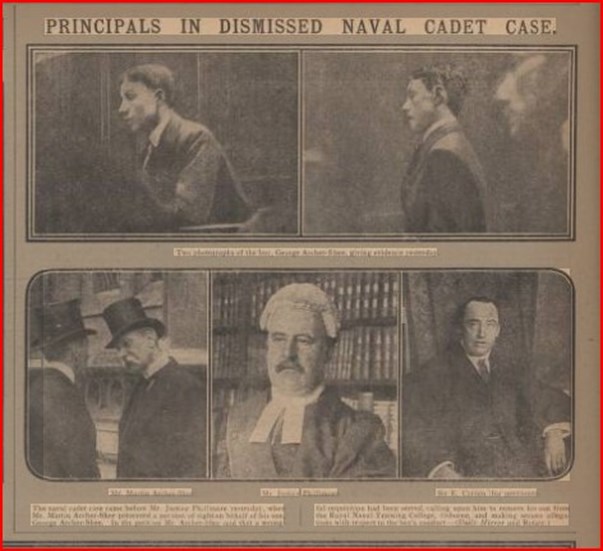

The Petition of Rights trial took place before Mr Justice Phillimore in late July 1910. The court room was packed – with several Cadets from Osborne College and, as one newspaper would remark, ‘many fashionably dressed ladies’ in attendance in the courtroom. [1] Many column inches of newsprint would be devoted to the case over the 4 day trial. Such was the interest in the case that by the third day, Sir Edward Carson indicated that he was feeling severely unwell due to the heated and close atmosphere within the court. Mr Justice Phillimore was sympathetic and indicated that the gangways in the court room should be kept clear.

Above: a Daily Mirror picture of the principals in the case.

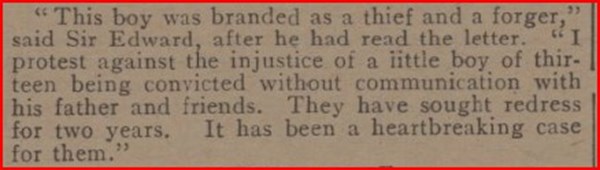

Sir Edward Carson’s case essentially focused on the stigma that the Admiralty’s action had placed on George.

Above: an excerpt from a Daily Mirror report of the trial on 27 July 1910.

Over the next days of the trial, the key players in the events that took place in 1908 were examined and cross examined, with detailed press reports of their statements. George gave evidence on the first and second day of the trial.

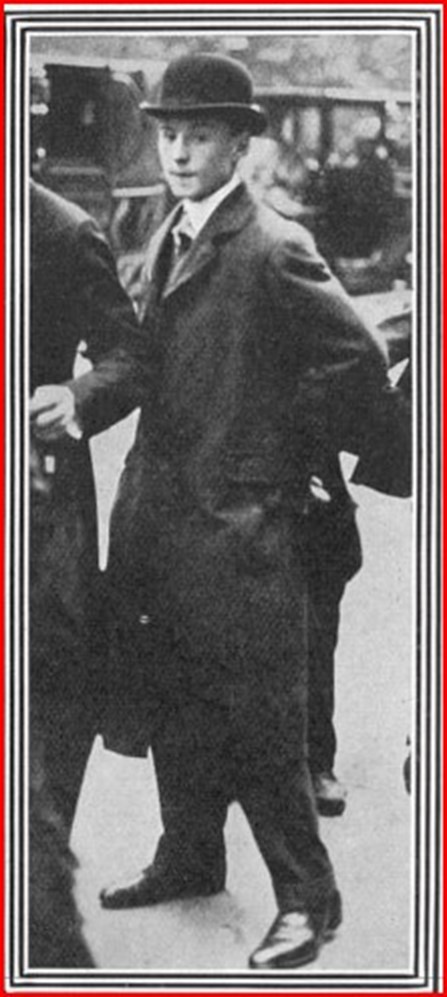

Above: George Archer-Shee attending the trial, pictured in The Tatler 3 August 1910

Much of the Admiralty’s decision on George’s future at Osborne had rested on two key points – firstly, the statement from the postmistress that the boy who bought the postal order also cashed one and secondly, that the handwriting on the cashed postal order was stated by a handwriting expert to be George’s.

Miss Tucker, the postmistress was called as a witness by the Crown and then cross examined by Sir Edward Carson.

“So conclusive was Sir Edward's cross-examination that it seemed it must be the end of the case. The Solicitor-General, in his address to the jury, had relied on the single issue that the cadet who bought the order for 15s. 6d. cashed the one for 5s. The only testimony that this was so, was that of the postmistress, and the cross-examination left little, if any, support for her opinion on this point”. [2]

It was expected that at some point the handwriting expert would be called by the Crown, but after hearing other evidence on the third day of the trial, the Court adjourned for the day. On the morning of the fourth day of the trial, the case came to an abrupt conclusion when the Solicitor-General indicated that he now accepted that George Archer-Shee was innocent of the charges against him.

Above: George Archer-Shee, described as looking ‘radiant’, pictured with his mother, sister and a family friend in Hyde Park following the trial – Daily Mirror 30 July 1910.

Although there were initial reports that George would be reinstated as a Cadet, the Admiralty refused to do so and George continued his education at Stonyhurst. His vindication generated many headlines, with press reports calling for compensation. The question of compensation to the family also came up in Parliament. A later judicial review did take place, with the family being awarded £4,120 to cover their costs and £3,000 compensation (a sum equivalent to £740,000 in 2020 terms).

George’s father died on 27 March 1913. Two months later, George was gazetted 2nd Lt in the Special Reserve in the 3rd South Staffordshire Regiment in May 1913. On 13 December 1913, he set sail for New York from Liverpool to work in a Wall Street firm. His departure was just a week after his sister Helen’s death from meningitis at the age of 14 years.

George returned to England just after the outbreak of war on 15 August 1914 and was attached as Lieutenant to the 1st Battalion of the South Staffs, arriving in Zeebrugge with the Battalion on 7 October 1914. He was reported wounded and missing on 31 October 1914 near Ypres. His mother placed advertisements in newspapers seeking any information but by May 1915, it was reported that ‘no hope was entertained’.

As his grave was never located, he is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres.

Above: Lt George Archer-Shee. Photo - © IWM HU 112949

A press report of George’s death included words from his Commanding Officer, Colonel Ovens:

“He was a most promising young officer, and in the short time that he was in the 1st Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment he earned the love and respect of both officers and men, and by his bravery and example contributed largely to the success of the battalion in the action near Ypres”. [3]

Above: The Menin Gate Memorial (image CWGC 2022)

Article by Jill Stewart, Hon. Secretary, The Western Front Association

References:

[1] The Globe - 26 July 1910

[2] University of Pennsylvania Law Review - June 1939

[3] Gloucester Journal – 8 May 1915