The Shot At Dawn Memorial

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Shot At Dawn Memorial

In May 2001 HRH the Duchess of Kent officially opened the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, Staffordshire, after a seven-year fundraising campaign in which many members of the WFA had been highly active.

Some 150 acres of land had been gifted for the project at this time and more than 40,000 trees planted. In addition, a visitor centre and Millennium Chapel had been completed.

A month later another official dedication took place on the site, as the new Shot At Dawn Memorial was unveiled.

The question of military executions for cowardice, desertion and less common offences such as mutiny, treason and murder, had been passionately debated throughout the Great War and raised repeatedly in the Houses of Parliament.

The unveiling of this new memorial was timely for supporters of the then highly active Shot At Dawn campaign group, which sought posthumous pardons for the majority of the executed men.

The unveiling of the Shot At Dawn statue by Mrs Gertrude Harris

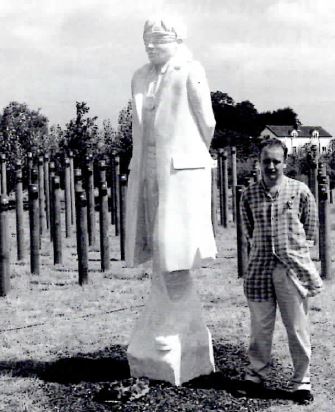

Sculptor Andy DeComyn with his memorial at the unveiling ceremony.

A close up of the memorial based on Private Herbert Burden.

A more recent picture of the memorial with the rows of wooden stakes each representing a man.

The British government had, to that point, continually ruled out retrospective pardons, although it did recommend that war memorials, and other records, include the names of executed men. This was to change in 2006, when it was announced that pardons would be granted.

One of the leaders of the campaign that forced the government’s hand was Mrs Gertrude Harris, who was the daughter of Private Harry Farr, executed for cowardice on 18 October 1916. It was Gertrude who unveiled the Shot At Dawn statue at the Arboretum, and she spoke movingly to some of those present about having been just three-years-old when her dad was executed. She would not learn about the true nature of his death until she was 40, because of the shame that she says her mother had been forced to feel.

Private Farr had fought at Neuve Chapelle and the Battle of the Somme, but on four separate occasions during these periods of 1915 and 1916 he had reported sick with nerves. During his worst spell he spent five months in hospital with symptoms that appear to have been consistent with the diagnosis of "shellshock". Harry then returned to action with the West Yorkshire Regiment but was court-martialled after refusing to go back in the trenches in September 1916, having asked to return to camp after saying he could not stand the noise of the artillery. None of his medical history appears to have been given to the court martial and he was found guilty in October 1916 of "misbehaving before the enemy in such a manner as to show cowardice".

Private Harry Farr, the father of Gertrude Harris.

Harry was put before a firing squad the next morning, aged 25, where he refused a blindfold - preferring to look his firing squad in the eye. The Army chaplain at the execution sent Harry's widow a message saying "a finer soldier never lived".

When the news of the pardon came through, his daughter, then aged 93, said: "I am so relieved that this ordeal is now over and I can be content knowing that my father's memory is intact. I have always argued that my father's refusal to rejoin the frontline, described in the court martial as resulting from cowardice, was in fact the result of shellshock, and I believe that many other soldiers suffered from this, not just my father."

Of course, one of the main points of contention about a blanket pardon had been that not all of the cases were so clear and that generalisation was dangerous. Indeed, the Shot At Dawn campaign had itself not sought a pardon for all, accepting that some of those executed were serious repeat military or criminal offenders, and even murderers.

Interestingly, those found guilty of crimes such as murder are not commemorated by name at the striking memorial at the Arboretum, which was funded mainly by individual donations.

Response to the memorial was positive from the outset. It features at its centre a figure created by Andy DeComyn, a Birmingham-based sculptor, which stands at over eight-feet. The figure has his hands tied behind his back and is blindfolded, whilst around his neck hangs an aiming-disk centred on his chest. In front of the figure are six conifers representing the firing-squad and behind are 306 wooden stakes each with the name, age, regiment, rank and date of death of an executed British or Commonwealth soldier.

The main figure is based on Private Herbert Burden who, at 16, added two years to his age in order to enlist in the Northumberland Fusiliers. He deserted at Ypres after his unit suffered huge losses and was court-martialled on 2nd July 1915 and executed on 21st July at the age of 17. Despite his age, he was undefended at his trial and, because of his battalion's heavy casualties, no character witnesses were provided.

Article by Dr Martin Purdy