The Sinking of the RMS Falaba, 28 March 1915.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Sinking of the RMS Falaba, 28 March 1915.

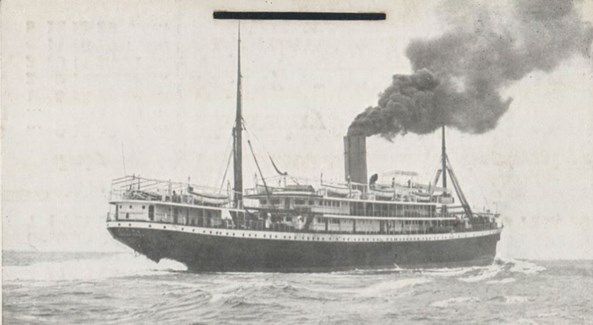

The RMS Falaba was sunk by a German submarine on 28 March 1915. This incident, and that of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania some weeks later, nearly brought the USA into the war in 1915.

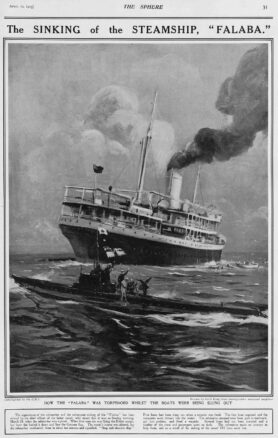

Above: The passenger steamer Falaba, sunk 28 March 1915, with the loss of 104 lives. Many were West African crewmen. Source: State Library of Victoria, Australia.

Whilst the sinking of the Lusitania is well known, the sinking of the Falaba, some 38 miles to the west of the Smalls, Pembrokeshire, on her way from Liverpool to Sierra Leone is almost forgotten today. The sinking resulted in the loss of an US citizen called Leon Thrasher, hence the reason this is sometimes remembered as ‘The Thrasher incident’.

Warning was given by the submarine U-28 commanded by Freiherr Georg-Gunther von Forstner (1882-1940) for the crew of 95 and 147 passengers to take to the boats, but before they could do so a torpedo was fired, and the vessel sank almost immediately.

A total of 104 passengers and crew were killed in the explosion, by drowning or from hypothermia caused by freezing cold seas. The RMS Falaba was the first unarmed passenger ship to be attacked in the war, and in the days following newspapers from around the world published reports of the horrific scenes and harrowing witness accounts from an inquest held in Milford Haven.

Above: The Evening Star (Washington DC) 31 March 1915.

Above: New York Tribune 31 March 1915

Above: An artist's impression of the sinking of the SS Falaba.

The Falaba was a passenger and cargo ship of 4,806 tons, built in 1906. When the Falaba set sail on 27 March 1915 she carried a crew of 95 and 147 passengers plus a cargo estimated at £50,000 (over £5 million today). The cargo included 13 tons of cartridges and gunpowder so in that sense was a legitimate target.

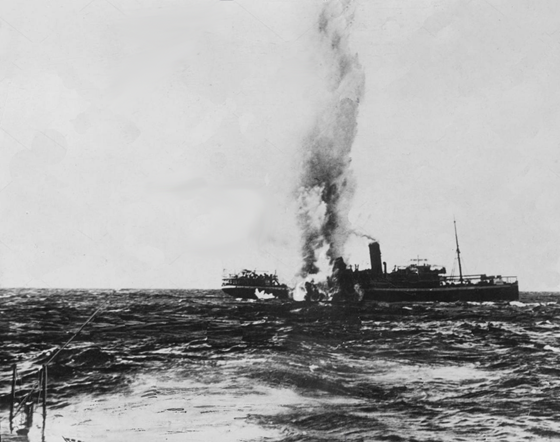

At 11.40 on the morning of 28 March 1915 as she was steaming 38 miles west of the Smalls lighthouse off the Pembrokeshire coast a submarine was sighted. The German admiralty had declared the waters around the British Isles a war zone on 4 February 1915.

The submarine U-28 had sunk the passenger ship Aguila the previous day with the loss of eight lives. Captain Davis of the Falaba tried to outrun the submarine but he soon realised he could not outpace her. Two distress wireless messages were sent and the Falaba stopped engines. The U-boat captain Forstner ordered the Falaba ‘s Captain to abandon the ship prior to setting about the sinking of the cargo vessel.

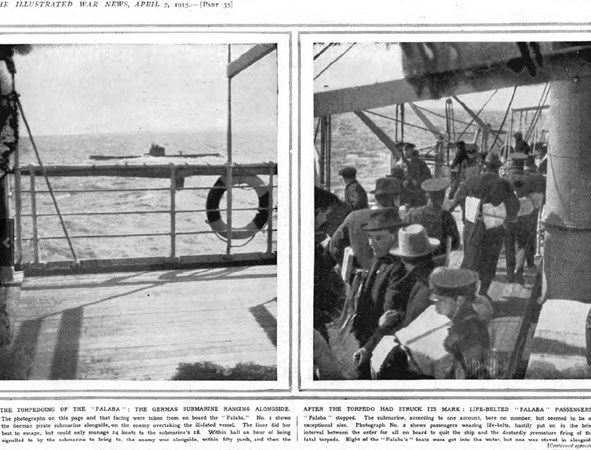

Above: "The Torpedoing of the 'Falaba'." The Illustrated War News 35 (7 Apr 1915): 42-3.

The Illustrated War News took up the story with the following:

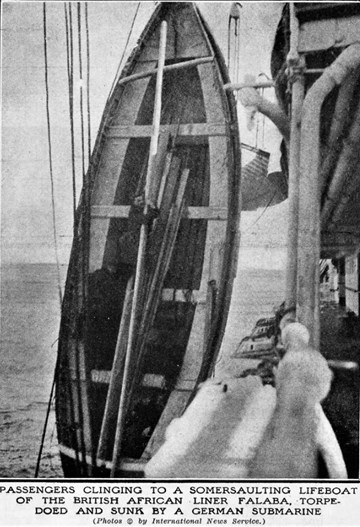

The photographs on this page and that facing were taken from on board the "Falaba." No. 1 shows the German pirate submarine alongside, on the enemy overtaking the ill-fated vessel. The liner did her best to escape, but could only manage 14 knots to he submarine's 18. Within half an hour of being signalled to by the submarine to bring to, the enemy was alongside, within fifty yards, and then the "Falaba" stopped. The submarine, according to one account, bore no number, but seemed to be of exceptional size. Photograph No. 2 shows passengers wearing life-belts, hastily put on in the brief interval between the order for all on board to quit ship and the dastardly premature firing of the fatal torpedo. Eight of the "Falaba's" boats were got into the water, but one was staved in alongside the steamer, all in it being thrown into the water, while another was being lowered when the submarine's torpedo struck the liner's hull directly underneath, capsizing the boat, and throwing its occupants into the sea. Had the ten minutes' grace named by the commander of he submarine been given, all the boats might have been launched safely and no lives been lost. Photographs Nos. 3 and 4 show the capsized boats and some of the people clinging to their keels, while others are struggling for life in the water. Several of the survivors declared, on landing and the coroner's inquest, that the Germany on the submarine's deck, with inhuman callousness, mocked and jeered at the drowning.

Unfortunately the evacuation that followed was chaotic and disorganised – not surprising perhaps as the Falaba had been told they had just five minutes to undertake the evacuation.

Above: Photo by International News Service. The New York times. [New-York N.Y] (New York, NY) 18 Apr. 1915, p. 3. Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Only four lifeboats had been successfully launched before the torpedo struck. The Falaba sank bow first in only eight minutes and 104 people, 53 of them crew members, died either in the explosion or to the effects of the freezing cold waters. The crew of the U-boat were accused of laughing and mocking the efforts of those in the water as they struggled to survive.

Above: Image of the torpedo striking the Falaba

Sergeant Hubert Blair, of the Royal Army Medical Corps, was among the passengers. Speaking to a Daily Mail reporter the day after the attack, he said:

“The captain ordered us into the boats. About 20 men got into the first boat, but directly that it touched the water, it capsized and men were thrown into the sea. Three other boats got off. The last was touching the water when the submarine fired a torpedo at us. It struck right under my boat, which was blown to pieces. Then the Falaba went down, head first, in less than five minutes. All the while, the submarine was standing by and watching us struggle in the water. They didn’t make the slightest attempt to help us, but the crew, or some of them, gathered on deck and laughed and jeered at us. All at once the sub submerged and disappeared. She was a large submarine, quite the largest I have seen.”

Above: Artists impression from The Sphere

The trawler Eileen Emma saved 116 people from the Falaba including 40 from the water. Sadly, six of these died shortly afterwards. The drifter Wenlock rescued another eight survivors of whom two died later. The survivors and victims were taken into Milford Haven.

One of the victims was Leon C. Thrasher, a 31-year old mining engineer from Massachusetts, the first United States citizen to be killed in this first period of unrestricted U-boat warfare. Thrasher's remains washed ashore on Ireland's coast on July 11, 1915, after it had been in the water for 106 days. Initially, authorities mistook him for a RMS Lusitania victim and designated him Body No. 248

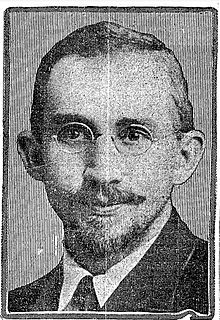

Above: Leon Chester Thrasher who died on RMS Falaba

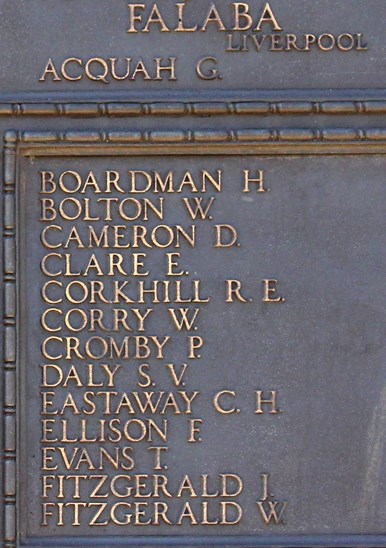

Funerals were held at Milford Haven as the bodies of the victims, including Captain Davis, were repatriated from the railway station to their respective families across the country. The only one who was interred locally was John Myers a young Nigerian coal trimmer, who was buried at Milford Haven cemetery on 1 April 1915 in a ceremony conducted by the Rev F. T. Oswell. His name appears with others who were drowned in this incident on the Tower Hill memorial in London.

Above: A panel from the Tower Hill Memorial

Above: The southern face of the Tower Hill Memorial

Another survivor was Jabez Massaquoi. Jabez was the grandson of a Liberian tribal chief. After abandoning ship, he caught sight of a “raft” floating in the water – which may have been little more than floating debris – and kicked towards it. He grabbed hold and hauled himself out of the freezing water. But then he caught sight of two Red Cross nurses, who were beginning to lose their fight against the ocean. The heavy skirts of their uniforms were slowly dragging them down.

Jabez plunged back into the water and swam over to them, he managed to pull them both to the raft and helped them climb on board. Speaking to The Stoke Sentinel in 1967, Jabez said:

“The nurses insisted I was given the same treatment as themselves and when we finally got back to London, the local authorities looked after me very well and appreciated what I had done. I was cared for and did not have to go to sea for three months.”

Above: Jabez Massaquoi, pictured with his wife Lillian in 1967. (Stoke Sentinel)

The incident caused the US President Wilson to speculate that international law had been violated, and the later sinking of the Lusitania prompted the Americans to send a diplomatic note to the Germans asking for an apology and reparations for both ships. The note included a warning that the US would take "any necessary act in sustaining the rights of its citizens or in safeguarding the sacred duties of international law".

However, after persistent requests by US Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, documents detailing witness statements from the sinking of Falaba offered proof that the captain of U-28 gave adequate warnings and time for Falaba to offload passengers. Instead, the crew of Falaba had used that time to radio the position of the submarine to nearby armed British patrol ships. As the warship approached, the submarine fired at the last minute and detonated nearly thirteen tons of contraband high explosives in Falaba's cargo.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

There is a copy of the British inquiry into the sinking of the RMS Falaba via this link Report on the Falaba