The Somme Film - Some Notes Gun Fire

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Somme Film - Some Notes Gun Fire

[This article first appeared in the Yorkshire Branch journal ‘Gun Fire’ Book 1 1985 pp9 - 15. The entire series of 59 editions published between 1985 and 2004 has been digitised by The Western Front Association and is available to members via their Member Login. A list of all articles across the 59 editions is available by clicking on the icon below which is captioned 'Gun Fire - Full Contents listing'. Additional images have been added to illustrate this article.].

First World War buffs will have awaited Channel 4's second instalment of the Flashback series with great anticipation - and they will have been disappointed. It was given a great build-up in the TV Times (1) and See (4), (2) and in the former readers were told that 'for the first time' it was to be revealed 'that some scenes' in the Battle of the Somme film 'were faked'.

This is preposterous, particularly when it is born in mind that in the list of credits appeared the name of Kevin Brownlow, who in The War, the West and the Wilderness (1978) identified an eye witness of the making of the famous attack scenes at a trench mortar school well behind the lines. It has frequently been mentioned in print that these scenes were faked; the give-away being the lack of equipment carried by the men involved.

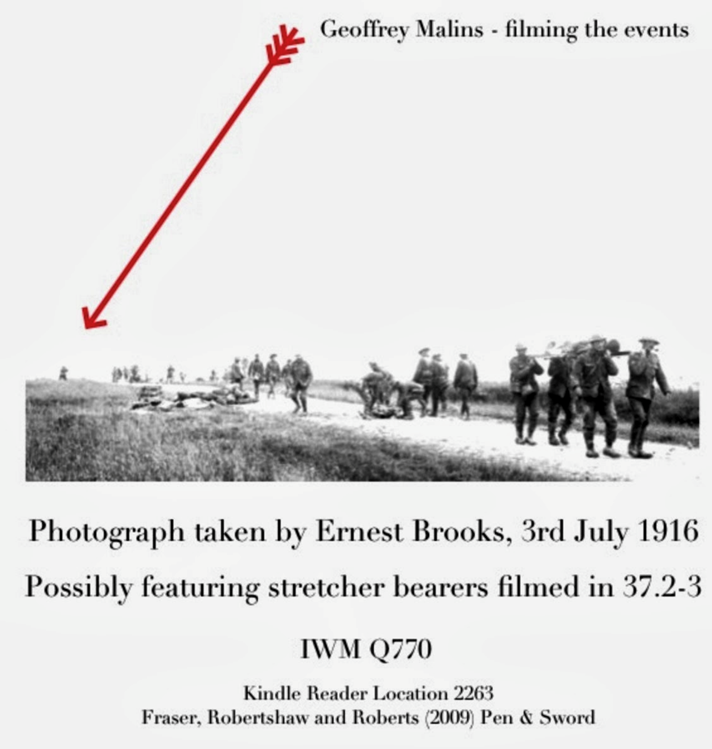

Another pointer to the fact that the scenes of the attack were faked comes from internal evidence in the film itself. Geoffrey Malins was the only cameraman on the 29th Division's front and he filmed the explosion of the Hawthorn mine from a sap in front of the line. (He draws a map of his position in his absurd biography.) (3) How then could he have filmed those men going over the top from behind, just ten minutes later? (4)

When were the dramatic shots of the men going over first recognised as being faked?

Certainly 60 years before the Flashback programme. In May 1922 a number of very distinguished soldiers looked at the film and damned the famous sequence (though one pronounced that the surroundings of the mine explosion did 'not appear genuine'). (5) But some of the people who saw it in 1916 must have realised that the men of 1 July did not go over as Malins showed. In September 1916, for example, Bioscope recorded that the film had been seen by 700 officer cadets from the 10th Officer Cadet Battalion, and by wounded soldiers at Huddersfield. (6) Surely these, or some of them, spotted that something was amiss. But is there any evidence that they did? There was rigid press censorship, of course, and adverse comments on the film would surely have been suppressed, yet there are snippets of information which suggests that the word might have been going round that all was not genuine. The Nation, for example, while enthusing about the film, spent some time on the question of "takes", which' it said, were 'easily detected' and presumably not present in Malin's work. (7) Shortly after the war The Record New Illustrated Weekly said that when the film was 'first shown ... many people, "unable to believe their eyes", had a strong feeling that these pictures were "fakes" -that is, doctored up with smoke-clouds, etc., in nice soft places well behind the lines, such as Army Schools, etc.'. (8) and when the film first came out the Sphere carried a conversation said to have been heard in the underground, which recorded some scepticism. (9)

"Seen these war pictures?"

"The Somme films? Yes, they're good".

"Are they faked?"

"No-o-o; they couldn't fake 'em. You see 'em. Why one of our fellers knows the very bit of trench ... you see 'em fall ... No, they're all right".

It is interesting to note that The Sphere chose the very piece of the film which was faked to prove it a true account, and certainly those scenes are the ones which are the most memorable, proving perhaps, as D. W. Griffiths realised with Hearts of the World, that the real thing is less dramatic (or more difficult to film) than the recreated. The Battle of the Somme was the limit of realism, and the 'great moment in the film', recorded one provincial critic, 'is the morning of advance. It is here that the casualty list in all its grim reality is seen. From the first line of trenches we see our men climb the 8ft parapet which takes them into the open, with sudden death as the reward of their impetuous bravery'. (10) A York paper similarly singled out the attack sequences for special mention ' ... the gallant soldiers are seen to swarm over the parapet. Two or three are seen to fall victims of the German fire within the first two or three yards. It is all so real that its very reality comes as a shock to the person who does not know the fearful toll which war demands'. (11) The 'pictures are at times just bearably real', wrote another critic, who also spoke of the film as being 'weirdly realistic'. (12) It was 'the real thing at last' recorded the Manchester Guardian, (13) and, when it was first shown in Manchester, 'There were cheers when the men first went over the parapet, but they died down to silence before the vision of the still, lifeless figure slipping back into the trench and the bodies just beyond the parapet'. (14) There 'is nothing more stirring than the sight of the infantry rushing over the parapet to the attack, some of them falling even before they have cleared our wire' said the Times. (15) After singling out the same sequence the Illustrated London News, on 26 August, said the film contained 'the most wonderful'. scenes ever 'thrown upon a screen'.

So impressed were the public with the Somme film that Conan Doyle and others campaigned for the cameramen's names to 'be flashed upon the screen'. (16) Eventually Malins and R. B. McDowell were named, and the Times wrote that Malins filmed 'the leap from the trenches' on 1 July 'and other stirring pictures from such exposed positions that he had to be called away' (17) A myth was started.

But were all those initial doubts lulled? Surely not, but there is little to prove so, beyond, perhaps, the kind of remarks made by the Yorkshire Evening Press about the second of the Somme films, The Battle of the Ancre. The Press deliberately told its readers to note that the new film contained 'nothing in the nature of "fake" or "made-up" scenes, having actually been taken on the battlefield'. (18) This is negative evidence, surely, but it could well be an indication that Malins' fake had been spotted. It must have been.

What else is doubtful in the Somme film?

There is a document at the Imperial War Museum analysing the 'shot sheet' and 'dope sheet' of the film and suggesting parts which are doubtful. In addition to these there may be others. The shot of the trench mortars being fired for example. (A still from the sequence is produced in M. Middlebrook, The First Day on the Somme (1971).) Is this genuine? Could Malins (who said he took it on 29 June) have taken the film from the depths of a dug-out with his equipment; and surely the soldier firing the gun would have been wearing a steel helmet?

Just before the famous attack scenes (which incidentally were re-used in the film Forgotten Men) there are shots of 'A Lancashire battalion awaiting instructions fixing bayonets and passing through communications trench to the front line'. Stills from the sequence (or a shot of the incident taken by a still cameraman) are frequently used as illustrations, and the I.WM. document says that they are 1st Lancashire Fusiliers 'filmed by Malins on 1st July at about 6.30 a.m. from the "White City" position about fifty yards behind the front line at Beaumont Hamel'. This accords with Malins' account of 1 July, but not with that of a survivor. George Ashurst was in the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers, and in a MS autobiography described that particular sequence being filmed well before 1 July.

During the daytime we played cards in the dug-out getting quite used to the awful din. It was while having a game of cards one day that we were requested to go out into the trench and be Photographed, presumably just fixing bayonets ready to go over the top. It was only a few minutes of a job and we soon obliged, especially as the Photographer, or War Correspondent, or whatever he was, promised us a tot of rum and a packet of cigarettes for our trouble. Anyhow it certainly was the last Photo a lot of those gallant lads ever had taken.

Is Mr. Ashurst correct? He does not mention a movie cameraman, but did Malins have the time to take the shots earlier than 1 July? Mr Bob Grundy, of Ashton-in-Makerfield, has written an article about Mr. Ashurst and the famous photograph. Perhaps he will provide the answers to these queries.

Whatever its shortcomings, the Somme film is a remarkable historical record

It is this fact which might be responsible for many writers giving its maker (or at least Malins) more than his fair due. Lyn Macdonald in The Roses of No Man's Land tells her readers that 'In the early morning of 1 July 1916, . . . Geoffrey Mallen (sic) took his cinematographic camera into an assembly trench behind Hunter's Lane ... and filmed some soldiers of the 16th Battalion; The Middlesex Regiment ... as they waited to go over the top'. Now the soldiers Malins filmed were the 1st Lancashire Fusiliers, as has been shown, but Miss Macdonald goes on with her story as follows.' ... at ... Minden Post ... Geoffrey Mallen set up his cine-camera a little later in the day .... and filmed a queue of walking wounded, waiting four deep for attention'. ( 19) Now Minden Post was south east of Carnoy, straddling the road from Fricourt to Maricourt, a direct distance of some eight miles from where Malins was at 7.30 am, and to get there would surely have been a superhuman feat on 1 July. Where did Miss Macdonald get her story from? She appears to have followed one of the aforementioned I. W. M. documents which credited some of the Minden Post Sequences to Mal ins and the rest to McDowell (Filmed by Malins at Malins Post on 1st or 2nd July'.) But can this be so? Malins filmed the troops in the sunken road and the mine going up, then gave the impression that he shot the attack we know to be faked, (20) stayed to see several waves of troops go over, then filmed wounded returning and a rescue in No Man's Land. Later he took pictures of the 'ROLL-CALL AFTER THE FIGHT - the roll call of Seaforth Highlanders (and he used a still from the sequence in How I Filmed the War). 'I stayed in the trenches', presumably the original trenches, 'until the following day' he wrote 21) Had he been in Minden Post he would surely have mentioned it. S. D. Badsey, however, in an extremely well researched MS article about the first Somme film, wrote that 'It seems about noon', on 1 July, Mal ins 'motored down to join McDowell at the Minden Post dressing station, where they filmed the wounded of both sides'. (22) Perhaps Dr. Badsey drew this from what he himself called the I.W.M.'s 'suspect but possibly accurate dope sheet of the film' (23) but, as has just been seen, Malins' own account said he was nowhere near Minden Post. According to that (or my interpretation of it) he stayed near Beaumont Hamel then, on 2 July, went to Becourt Wood. He returned to England on the 3rd. (24) 'Thinking that the films I had obtained should be given to the public as quickly as possible, I suggested to G. H. Q that I should return to England without delay ... I returned to London the next day', he wrote.

If Malins got from Beaumont Hamel to Minden Post on 1 July, as Miss Macdonald said, he achieved a miracle - but it must be clear that, whatever his files said, he did not. A writer of the 1930s, however, perhaps influenced by existing stories of redoubtable journeys and brave acts, credited him with other superhuman feats. He 'was absolutely fearless', according to this source, 'and many of his films were actually taken running with the troops in action, with an Aeroscope camera, and their vivid actuality most certainly justified the taking of this very unusual risk.'(25) What film the author had in mind it is impossible to say .

There is a very interesting reminiscence which seems to be about the Somme film, which may illustrate how memory can play tricks on soldiers talking or writing about the war - and not very long after the event on this occasion. In a book published in 1917 F. Palmer described his experiences on the Somme. He was directly opposite Beaumont Hamel on 1 July, so would have seen the Hawthorn mine go up, and might well have seen Malins at work. (26) After describing the battle he wrote this. 'I saw only one incident of any harshness of captor to a prisoner. A big German ran against the wounded arm of a Briton, who winced with pain and gave the German a punch in a very human fashion with his right arm'. (27) This reads very much like a description of an incident in the first Somme film which is well known and follows the caption 'British wounded and nerve-shattered German prisoners arriving. Officer giving drink, and Tommies offering cigarettes to German prisoners'. (28) But this is one of the sequences definitely filmed at Minden Post and Palmer could not have seen it. If the incident he recalled is the same one, he must have thought he saw it after seeing the film.

There is a terrible temptation for writers who have challenged a piece of work and shown it to be unreliable to nevertheless use parts of it when it suits their case - and I am well aware that, having attacked How I Filmed the War, I have accepted Malins' account of where he was on 1 July. I have done this because (a) there are pieces of film which definitely fix him at certain places at certain times (6.30 am and 7.20 am for example) on that awful day, and (b) because I believe his self-glorifying and clear reluctance to give any credit to anyone else would have made certain that he wrote about that journey to Minden Post had he undertaken it. But the book is patently unreliable, and just how unreliable might perhaps be demonstrated by drawing attention to one of its illustrations. On page 123 there is a photograph which the caption says is of the author in a shell hole actually filming the British bombardment of the German lines before 1 July. 'I GOT INTO THIS POSITION DURING THE NIGHT PREVIOUS. IT WAS HERE THAT I EARNED THE SOUBRIQUET "MALINS OF NO MAN'S LAND'", Malins wrote, yet his text described him taking what are presumably these shots from 'a spot called "Lanwick Street".' There, he said, he went in daytime, and there he had to 'push away several sandbags which interfered with my view on the parapet', and prepared his camera 'by clothing it in an old piece of sacking'. (29) There is no parapet in the still, and no covering on the camera - and to make the whole thing even more unbelievable Malins is wearing only a cloth cap. In all probability the shot was taken at that same trench mortar school where the attack scenes were made. It has the same slap happy appearance.

The still just mentioned is reproduced in one of the volumes of I Was There, (30) though without Malins' sensational caption. There is another publicity photograph of him, immaculately dressed and 'polished in the actual fighting line' in The Pageant of the Century (no date) page 327. It may well have been 'the actual fighting line' at some stage, but the war had moved very far away when this photograph was taken.

That parts of the Somme film were faked has been long known, so it is both surprising and annoying to read of it still being accepted at Malins' valuation of it, as in the following extract from a book by a lady called Ann Purser. In Looking Back at Popular Entertainment 1901 - 1939 (Wakefield 1978), a book written in a familiar, 'jokey', intensely annoying style she tells her reader about Malins' epic. But had she seen it? It seems not. Except for a few shots of gunners firing in bad conditions all the action takes place in fine weather, and tanks, of course, are simply not there. 'Long feature films about the war were made', she wrote,

and the most famous was The Battle of the Somme, shot in July 1916. Can you imagine the effect on those left at home, with no nightly Television or radio news broadcasts, and with newspaper reports that often selected only the good news? Here was a film of their sons and husbands actually fighting in the mud, tanks crawling along across battlefields and troops being killed. Not everyone approved.

- S. J. Gilheany, 'How Armageddon First Came to the Screen', Yorkshire T. V. Times 1 - 7 October 1983

- See 4 No. 4, Autumn 1983

- G. Malins, How I Filmed the War (1920)

- The sequence is frequently reproduced, for example in J. Ellis, EyeDeep in Hell. Life in the Trenches 1914-1918 (1977)

- Lt. Col. H. C. Fergusson

- Bioscope 14 and 28 September 1916

- The Nation 26 August 1916

- The Record New Illustrated Weekly 31 January 1920

- The Sphere 23 September 1916

- Hull Daily News 29 August 1916

- Yorkshire Evening Press 25 August 1916

- Hull Daily Mail 25 August 1916

- Manchester Guardian 11 August 1916

- Ibid 29 August 1916

- Times 11 August 1916

- Ibid 4 September 1916

- Ibid 5 September 1916

- Yorkshire Evening Press 30 January 1917

- L. Macdonald, The Roses of No Man's Land (1980) p. 160

- Malins op.cit.p.163

- Ibid p.171

- S. D. Badsey, 'Filming the Somme. An Episode in British Propaganda During the First World War'. p.13

- Ibid fn. 32

- Malins, op,cit.p. 171 and 176

- L. Warren, The Film Game (1937)

- F. Palmer, With the New Army on the Somme (1917) p. 63

- Ibid p.88

- Middlebrook, op.cit. uses a still of the incident

- Malins, op.cit. pp. 130-31. My italics

- J. Hammerton, editor, The Great War ... I Was There (no date) Vol. l .p.673.

A.J.Peacock