Tolkien’s “bitter winnowing” and the War Memorial at St. Augustine’s Church, Edgbaston

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Tolkien’s “bitter winnowing” and the War Memorial at St. Augustine’s Church, Edgbaston

The war memorial at St. Augustine’s of Hippo - parish church of Edgbaston, Birmingham – is intriguing for several reasons. Firstly, one of those listed on it was a school-friend of celebrated local author, J.R.R. Tolkien. The other men inscribed on the monument also provide a revealing snap-shot of the socio-economic character of the district, at the time of the Great War. When it was unveiled, in 1921, Edgbaston was the largest parish in the city, with a “rising population.”[i] Finally, the elaborate process by which this unusual memorial came into existence was recorded in a parochial minute book, now held in the archives at Birmingham’s Central Library, Centenary Square.

Above: View of St. Augustine’s church from the west.

Above: View of the church and war memorial from St. Augustine’s Road, Edgbaston.

Sir John Barnsley

The St. Augustine’s memorial was officially unveiled on the evening of 28 July 1921, by Brigadier-General Sir John Barnsley (1858-1926)- one of Birmingham’s “best known and highly respected public men.”[ii] He was head of Messrs. John Barnsley & Sons, the construction firm that built the city’s Council House, Art Gallery and - in 1925 - the Hall of Memory. However, it was for “services” to the Territorial movement that Sir John was knighted, on 26 June 1914.[iii] When war broke out, he seized the initiative and raised three New Army battalions for the Royal Warwickshire Regiment (RWR): the 14th, 15th and 16th battalions.[iv] Sir John’s crucial role in thus creating the ‘Birmingham Pals’ led to him being described as the city’s “chief recruiting officer.”[v]

Above: ‘First Church Parade of the 14th Battalion the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, under the command of Colonel Sir John Barnsley.’[vi] Sir John, with his dark moustache, can be seen immediately following the police bass-drummer.

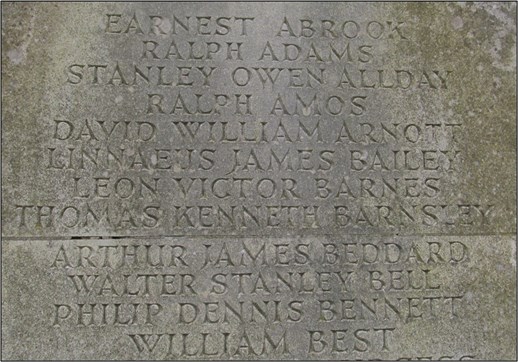

At the unveiling ceremony, Sir John told the large crowd that men from their parish had fought “to save all mankind from a vast conspiracy against the liberty of the world.” For this, he continued, “we had paid a great and precious price… the blood of our sons.”[vii] In his case, these comments were quite literally true, for the eighth name listed on the St. Augustine’s memorial was that of his own son: Thomas Kenneth –‘Tea-Cake’– Barnsley, school-friend of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien.

Who was ‘Tea-Cake’ Barnsley?

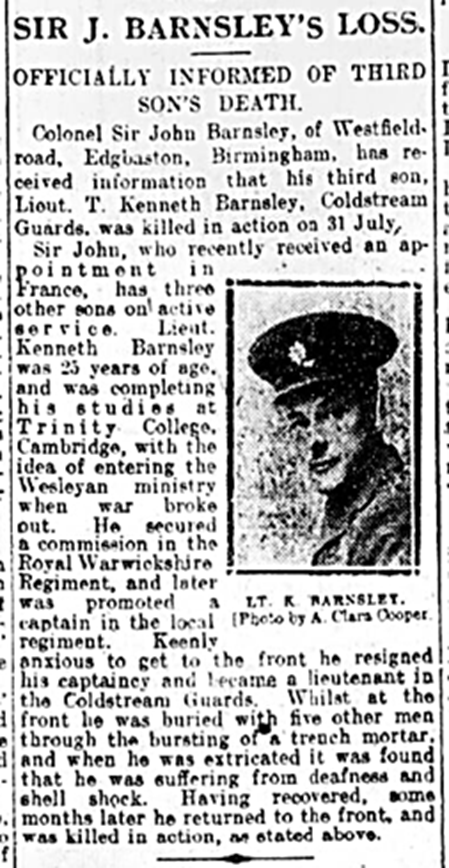

T.K. Barnsley (1891-1917) met Tolkien when they attended King Edward VI’s School (1908-11); then situated in New Street, Birmingham. ‘Tea-Cake’ - as Barnsley was promptly nick-named - became a peripheral member of the famous coterie of school-chums known as the ‘Tea Club and Barrovian Society’ (TCBS). The four most prominent members of this select band were Robert Q. Gilson, Geoffrey B. Smith, Christopher L. Wiseman, and Tolkien himself. However, other pupils were TCBS ‘casuals’, such as Ralph Payton and the “unflappably light-hearted” ‘Tea-Cake’, who dominated the group with his “brilliant wit”.[viii] After leaving school, Barnsley studied History at Trinity College, Cambridge, with the ultimate intention of entering the Wesleyan ministry. However, his graduation coincided with the outbreak of the Great War and he became one of his father’s first officer recruits to the 14/RWR. Barnsley received his commission on 1 October 1914 and was soon promoted to Captain’s rank. However, he was so “anxious” to get to the Western Fronthe resigned his captaincy in August 1915, and transferred into the Coldstream Guards, as a Second Lieutenant.[ix]Once in France, Barnsley was blown up and buried by a trench mortar, at Beaumont Hamel, in August 1916. Miraculously, he escaped serious injury, beyond a perforated eardrum and shell shock.[x]

Above: Thomas Kenneth - ‘Tea-Cake’ – Barnsley, in the uniform of the Coldstream Guards.

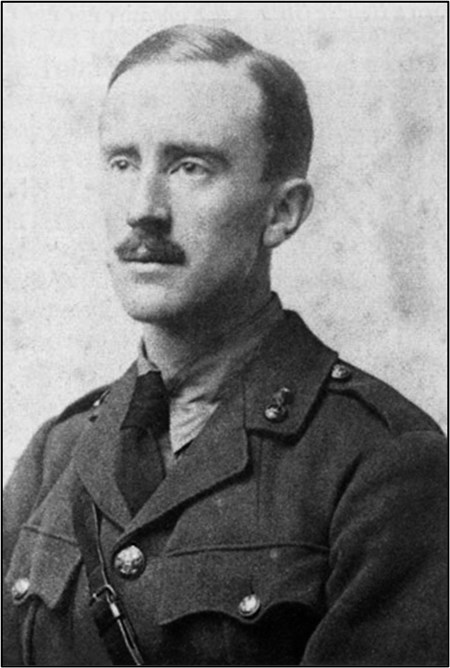

Above: J.R.R. Tolkien

It was whilst recovering at a military hospital, in his home town, that ‘Tea Cake ’conceivably met Tolkien for the last time. On 9 November 1916, a case of trench fever meant his old school-friend was also invalided home; to the 1st Southern General Hospital, at Birmingham University.[xi] Tolkien had also served on the Somme - with 11/Lancashire Fusiliers–and, prior to falling ill, taken part in the Battle of the Ancre Heights.[xii] Later writers have struggled to accept Tolkien’s assertion that the swamp-like conditions he witnessed, near the Zollern Redoubt and Mouquet Farm, did not inspire the “darker passages” in ‘The Lord of the Rings’.[xiii] However, he did eventually concede the “landscape” of the Dead Marshes, and “approach to the Morannon,” possibly owed “something” to the Somme battlefield.[xiv]

“They went slowly in single file: Gollum, Sam and Frodo…the hobbits soon found that what had looked like one vast fen was really an endless network of pools, and soft mires, and winding half-strangled water-courses. Among these a cunning eye and foot could tread a wandering path…Cold clammy winter still held sway in this forsaken country…They walked slowly, stooping, keeping close in line…it grew difficult to find the firmer places where feet could tread without sinking into the gurgling mud…”[xv]

It is tantalising to speculate whether ‘Tea-Cake’ and Tolkien actually met in late 1916, and exchanged their own experiences of the Somme. If such a reunion ever took place, no record of it exists. Tolkien was to spend the rest of his military career in the UK, whereas Barnsley returned to the Western Front and attained Captain’s rank, in the 1/Coldstream Guards. He was killed at Pilkem Ridge, on 31 July 1917,during the opening phase of the Third Battle of Ypres. The “wise-cracking”[xvi]‘Tea Cake’ Barnsley was buried in Canada Farm Cemetery, the former site of a British army dressing station, five miles north-west of Ypres.[xvii]

Above: The death of Lt. T.K. Barnsley, reported in the Birmingham Gazette, 8 August 1917.

A “bitter winnowing”

Although Tolkien always claimed the Great War provided no direct inspiration for the plot of ‘The Lord of the Rings’, the war had a devastating effect on his close circle of friends.[xviii] Along with ‘Tea Cake’ Barnsley, other members of the TCBS who died included key figures, Rob Gilson and Geoffrey Smith. Lt. Gilson (11/Suffolk Regt.) died on the Somme, on 1 July, and Lt. Smith (19/Lancashire Fusiliers) was killed south-west of Arras, on 3 December 1916. On a wider front – proportionally - the Great War “cut a deeper swathe” through the ranks of similar - middle-class - men than any other social group in the country.[xix] John Garth has been claimed one-in-five former pupils of public and grammar schools died in the war, and of the 1,403 ‘Old Edwardian’s’ who enlisted, 243 perished (17%).[xx] As Edgbaston –home to the “city elite” –was a district that provided many officers for the British army, it experienced a particularly high mortality-rate. This is demonstrated by an analysis of the Great War losses listed on the St. Augustine’s memorial. It has been possible to establish the military records of 76 of the 78 men recorded, of whom forty-one were officers (54%), and thirty-five Other Ranks (46%). It was in Tolkien’s letter to Geoffrey Smith, dated 12 August 1916 - commenting on Gilson’s death - that he referred to the war as a “bitter winnowing” of the TCBS.[xxi] However, this tragic metaphor accurately describes the Great War’s impact on the entire British middle-class; as exemplified by the St. Augustine’s memorial.

Above: The first twelve names on the St. Augustine’s memorial, with ‘Tea-Cake’ Barnsley the eighth one listed.

The Process of Erecting a War Memorial

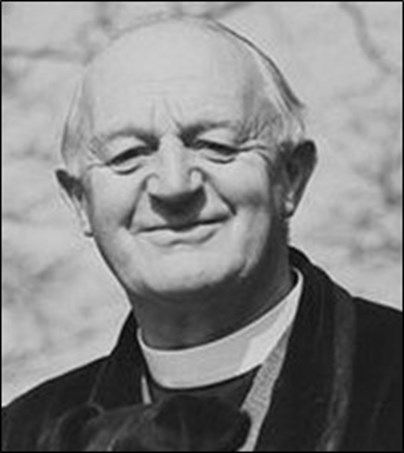

The following account is largely based on the minutes of the ‘St. Augustine’s Parochial War Memorial Committee’. The sequence of events that culminated in its unveiling began with an informal meeting, on Tuesday, 25 November 1919.[xxii] This was chaired by the vicar, Rev. Rosslyn Bruce (1871-1956) - a “devoted but unconventional parish priest”[xxiii] – and included other elders of the parish. On this occasion, key objectives for the proposed memorial were recorded. Firstly, that “it should include the names of all the fallen from the parish and subscriptions accepted from all denominations.” It was also agreed a letter should “be delivered to every house in the parish inviting support for the scheme and asking for names of the fallen.” Members of this informal group also arranged to contact leading figures in the other local religious denominations, namely: Archbishop McIntyre (Roman Catholics); Sir John Barnsley (Wesleyans); Mr Brindley (Congregationalists); Mr C.A. Vince (Baptists) and Mr Spiers (Jewish community). The final decision made was that the “price and design should not be limited… and …eminent artists asked to submit designs. ”Following this initial meeting, Rev. Bruce visited every home in the area and his appeal for donations encountered “no refusals”.[xxiv]

Above: the Rev. Rosslyn Bruce.

Above: Photograph from the Birmingham Gazette, 21 July 1917

The War Memorial Competition

On 6 March 1920, the formal election of the War Memorial Committee took place, and its fourteen man team now included: Rev. Bruce, Messrs Lowe, Keay, Lunt, Holroyd, Turner, Pearson, Brindley, Spiers, Vince, Hill, Wain, Ledsam and Murray. At this first official session, the committee agreed to approach Sir Whitworth Wallis (1855-1927) to act as judge of all designs submitted in the memorial competition. Sir Whitworth was curator of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; a post he had held since 1885.[xxv] Mr Keay also suggested the names of four artists who could be approached to submit designs: Mr Morcom, Mr Hatton, The Birmingham Guild and Lady Scott. The Birmingham Guild of Handicraft was an Arts and Crafts association of local artists, based in Great Charles Street, Birmingham. Lady Kathleen Scott (1878-1947) was an accomplished artist as well as widow of Captain Robert Falcon Scott, the Antarctic explorer. Her notable public works included statues of her late husband, in London’s Waterloo Place, and Captain Edward Smith of R.M.S. Titanic, in Beacon Park, Lichfield. However, Kathleen Scott was also the younger sister of Rev. Bruce, vicar of St. Augustine’s, a fact that must have generated discussion at the time.[xxvi]

Above: Lady Kathleen Scott.

Above: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery: built by Messrs. John Barnsley & Sons, and where Sir Wallis Whitworth was curator, in 1920.

The new committee met again, on 15 March 1920, at 4 Manor Road, Edgbaston; home of Rev. Bruce. On this occasion “it was resolved the memorial should be without Christian symbolism, while reflecting the spirit of Christianity as generally understood.” The committee therefore re-affirmed its initial commitment to erect an inclusive monument, sensitive to the religious beliefs of everyone in the local community. This, despite the fact Mr Mendelssohn, a Jewish resident, told Rev. Bruce, “Go on vicar, have a cross if you like. We don’t mind.”[xxvii] This meeting also confirmed the four artists who would take part in the competition: Mr Morcom, Mr Hatton, Lady Scott and “a London artist, (the names of Frampton Tweed or Rhodes were mentioned).” It was also agreed to pay the unsuccessful entrants,“£10 and ten shillings”, and the successful artist, “£550.” Ultimately, the cost of the completed project was £640-19s-1d.

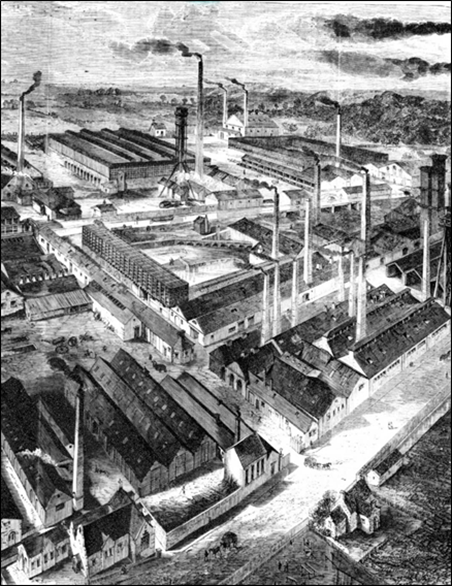

Above: Chance Brothers’ works at Oldbury produced chemicals for their glass factory at Smethwick. In the centre of this view, from 1862,are the ‘lead chambers’, where sulphuric acid was produced.[xxviii]

An interesting insight into the challenges facing monumental artists of this period was also identified at the meeting. The committee agreed the competitors must be warned about “the deleterious effect upon metal from the Oldbury Chemicals.” This was possibly a reference to the impact of pollution caused by Chance Brothers Alkali Works. This firm was based about three miles to the north-west of St. Augustine’s and known locally as, ‘The Acid Works’.[xxix] In 1920, Chance’s was the largest chemical plant in the Midlands, and its enormous chimney stacks released plumes of hydrochloric acid fumes into the atmosphere. Consequently, exterior metalwork in Birmingham suffered the corrosive effects of acid rain, and the contestants were advised to avoid including it in their final submissions. The decision, to appoint Sir Whitworth as competition judge, was also confirmed at the meeting on 15 March 1920. In a final attempt to ensure the accuracy of the memorial’s roll of honour, it was also “resolved to insert an announcement upon three successive Saturdays in the Birmingham Post” sono “names of fallen heroes” were omitted.

Announcing the winner

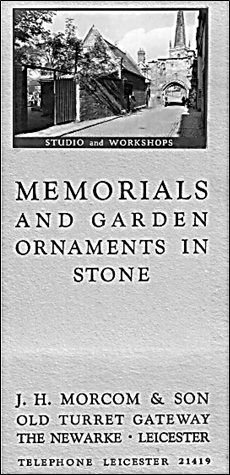

Thereafter, the memorial competition proceeded apace, and on 26 May 1920 Sir Whitworth informed Rev. Bruce he had chosen his favoured design. The wording of his letter suggests the selection process was managed with some degree of secrecy, and the actual names of competitors withheld from the judge. This subterfuge may have been due to Rev. Bruce’s well-known connection to Lady Scott. Sir Whitworth wrote, “after considerable deliberation I have decided to award the commission to ‘Turret’, subject to an interview with the artist.” ‘Turret’ was clearly an alias. Three days later, on 29 May 1920, a meeting of the committee was convened, “Turret’s envelope opened…and found to be the design put forward by Mr J.H. Morcom, The Newarke, Leicester.”

Above: This leaflet, produced in 1938, perhaps explains Morcom’s choice of alias in 1920.[xxx]

The Committee voted to accept Sir Whitworth’s verdict and thanked him for his expert guidance in selecting the winning entry. Then, “the other designs were inspected and admiration expressed,“ along with some, “not submitted for competition.” Sadly, the names of most unsuccessful candidates were never recorded, nor Sir Whitworth’s critical comments. However, Lady Scott’s entrywas possibly deemed inappropriate, ortoo unusual, compared with the many other war memorials then being unveiled. According to her niece, her failed submission languished in the corner of Rev. Bruce’s study for many months afterwards. It was a plaster model of a “naked youth, with one hand raised”, and dressed only in a skimpy loin cloth![xxxi]

Above: J.H. Morcom –seated front row with arms folded – and his workforce, in 1919.[xxxii]

Joseph Herbert Morcom

Joseph Herbert Morcom ARCA (1871-1942) had initially trained as a sculptor in stone with Norbury Paterson and Co. in Liverpool. He also studied at the Liverpool School of Architecture and Applied Art and was appointed modelling master at Leicester School of Art, in 1910.[xxxiii] Like many contemporary craftsmen, Morcom continued teaching whilst also working as a professional in his own field. In 1914 he bought a company of stonemasons and monumental sculptors called Pearson and Shipley, based at The Newarke, in Leicester. By the time Morcom’s entry was selected for the St Augustine’s war memorial, he had already created monuments elsewhere; notably the ‘temporary’ memorial in Leicester’s Town Hall Square, that was eventually demolished in 1954.[xxxiv] Nine months after his appointment at St. Augustine’s, Morcom contacted Rev. Bruce with a detailed drawing of the memorial and a final list of names to be checked before inscription. On 18 February 1921, Morcom indicated that the whole project would be finished “by the end of April” that year.

Unveiling the War Memorial, 1921

In the event, the final stages of the project took a little longer, and it was not until 13 July 1921 that Morcom personally supervised the raising of the monument. Two days later, the Church Council met on site to confirm the final arrangements for the unveiling and dedication ceremony. On 26 July, a set of railings were delivered and placed around the memorial, but these are no longer present. Then, on the evening of Thursday 28 July – the seventh anniversary of the start of the Great War - the St Augustine’s war memorial was formerly unveiled by Sir John Barnsley. The Birmingham Gazette called it a “plain, yet handsome, structure of white Portland stone,”[xxxv] whilst the Birmingham Post commented on the fact the memorial contained no “symbol of religious faith,” as it commemorated “the heroism of men of all creeds.”[xxxvi] Rev. Bruce’s daughter, Verily, described it as “a simple pillar, topped by a rosebud-like flame”, which was both a testimony “to the dead and the human charity of the living.”[xxxvii] Sadly, a century of acid rain and weathering has eroded the definition of the memorial’s original stonework, especially its four angels.

For Sir John Barnsley, the unveiling must have been a moment of intense private emotion, as well as one of immense civic pride. Following his address, the monument was formally dedicated by Rev. Bruce; the vital overseer of the whole process of planning, designing and erecting this inclusive tribute to all the “fallen heroes” of the parish.[xxxviii] The story of the St. Augustine’s memorial has revealed fascinating evidence about the people of Edgbaston, and their social attitudes, at the time of the Great War.

Above: Various views of the memorial. These show the effects of a century of weathering, especially on the four angels at the top.

I would like to express special thanks to Liz Palmer, Library of Birmingham, for her help in finding the Minutes of the St. Augustine’s War Memorial Committee.

Article by Quintin Watt

References

[i] Verily Anderson, Last of the Eccentrics – The Life of Rosslyn Bruce (London: Hodder & Stoughton,1972), p.211

[ii] Evening Despatch, 20 January 1926

[iii] Alan Tucker, On the Trail of the Great War, Birmingham: 1914-1918 (Studley: Brewin Books, 2014), p.75

[iv] J.P. Lethbridge, Birmingham in the First World War (Birmingham: Newgate Press, 1993), p.7

[v] Tucker, On the Trail of the Great War, p.76

[vi] R.H. Brazier and E. Sandford, Birmingham and the Great War, 1914-1919 (Birmingham: Cornish Brothers,1921), p.64

[vii] Birmingham Post, 29 July 1921

[viii] John Garth, Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle Earth, 2011, p.7

[ix] Birmingham Gazette, 8 August 1917

[x] Garth, Tolkien and the Great War, p.206

[xi] Daniel Grotta-Kurska, J.R.R. Tolkien: Architect of Middle Earth (Philadelphia: Running Press, 1976), p.51

[xii] Garth, Tolkien and the Great War, pp.194-199

[xiii] Grotta-Kurska, J.R.R. Tolkien: Architect of Middle Earth, p.46

[xiv] Humphrey Carpenter, Ed., The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (London: Harper Collins, 2006 [1981] ), p.303

[xv] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Part Two: The Two Towers (London: HarperCollins, 2012 [1954] ), pp.626-7

[xvi] Garth, Tolkien and the Great War, p.250

[xvii] The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, online database, accessed 2015.

[xviii] Carpenter, Ed., The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, p.303

[xix] Garth, Tolkien and the Great War, p.9

[xx] Tucker, On the Trail of the Great War, p.59

[xxi] Carpenter, Ed., The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, p.9

[xxii] Minutes of the St. Augustine’s Parochial War Memorial Committee, 1919-21, EP 87/5/5/1, Birmingham Library and Archives, Centenary Square

[xxiii] Birmingham Post, 25 January 1956

[xxiv] Anderson, TheLast of the Eccentrics, p.241

[xxv] The Dictionary of National Biography, 2013

[xxvi] Anderson, The Last of the Eccentrics, p.242

[xxvii] Anderson, The Last of the Eccentrics, p.242

[xxviii] Terry Daniels, Oldbury, Langley & Warley: Britain in old Photographs (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2002), p.18

[xxix] James Frederick Chance, A History of the Firm of Chance Brothers & Co., Glass and Alkali Manufacturers, 1919.

[xxx] Alan McWhirr, Joseph Herbert Morcom Sculptor (1871-1942) (University of Leicester pdf: le.ac.uk/lahs/downloads/2006

[xxxi] Anderson, The Last of the Eccentrics, p.242

[xxxii] Alan McWhirr, Joseph Herbert Morcom Sculptor (1871-1942) (University of Leicester pdf: le.ac.uk/lahs/downloads/2006

[xxxiii] 'Joseph Herbert Morcom ARCA', Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011

[xxxiv] Matthew Richardson, Leicester in the Great War, 2014, p. 112

[xxxv] Birmingham Gazette, 29 July 1921

[xxxvi] Birmingham Post, 29 July 1921

[xxxvii] Anderson, The Last of the Eccentrics, p.242

[xxxviii] Birmingham Gazette, 29 July 1921