‘Two years in the making. Ten minutes in the destroying’ – A Sheffield soldier at the heart of ‘Covenant with Death’.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- ‘Two years in the making. Ten minutes in the destroying’ – A Sheffield soldier at the heart of ‘Covenant with Death’.

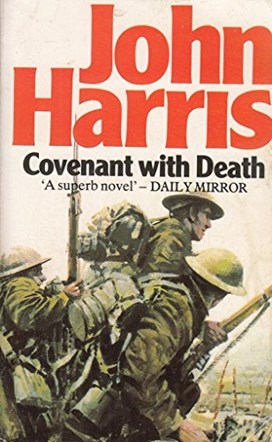

John Harris’s 1961 book, ‘Covenant with Death’, is a well-known ‘fictionary’ account of the Sheffield City Battalion, taking it from formation to catastrophe at Serre on 1 July 1916.

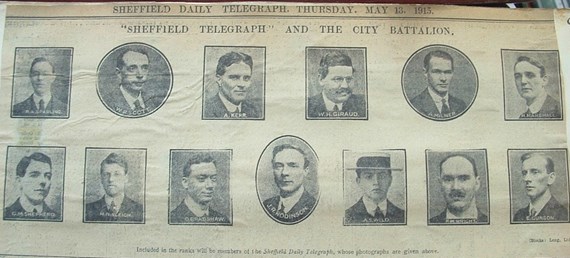

Harris (1916-1991), a Rotherham-born journalist, cartoonist and fiction writer (his list of publications is lengthy), worked for the Sheffield Telegraph both before and after the Second World War. Harris interviewed battalion survivors, but one such was a close colleague. The book’s central character, Mark Fenner, whilst naturally a composite, is partly based on his fellow reporter Jesse Richard ‘Roddy’ Rodinson – a matter handed down within the family with pride.

Above: An image from the Sheffield Telegraph (from May 1915). Rodinson is pictured in the centre of the lower row of images.

Harris would have met Rodinson in the mid-30s, and it seems highly likely that it was Roddy who galvanised Harris’s interest in the City Battalion and probably enabled his contacts. We do not know who else Harris spoke to, but the publisher of ‘Long Shadows Over Sheffield’ (2014) wrote of his grandfather, Harold Hickson, that: ‘The only person Harold ever confided in was author John Harris’. The Telegraph published the June 1916 diary of Lt J. L. Middleton in two issues in 1937 - it might be guessed that Harris was behind this.

‘Roddy’ Rodinson

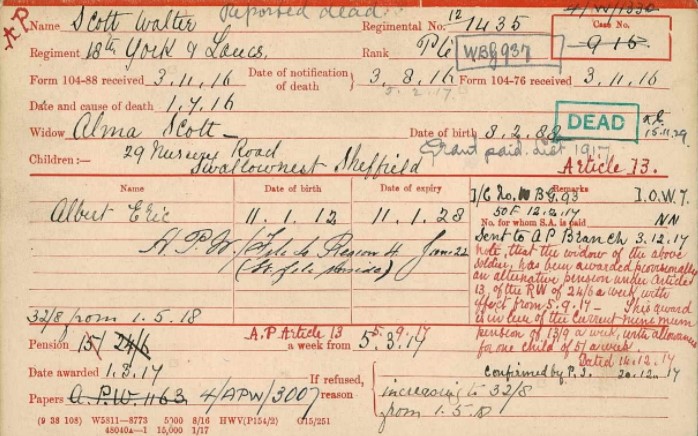

Born the son of Richard and Eliza Rodinson in Skipton in 1884, Roddy was working as a photographer’s shop assistant at the age of 17, and by 1911 was a ‘press photographic artist’, working for the Sheffield Daily Telegraph. Mark ‘Fen’ Fenner is ‘a reporter on the Post at the time’. Roddy enlisted on 11 September 1914 (Private 12/1033, 12th Battalion York & Lancaster Regiment) – ‘Covenant’ describes a group of journalists enlisting together. Roddy refers to two such; Sergeant R. A. Sparling, a Telegraph reporter, who later wrote a history of the unit; and Private W. R. Scott, another, who was killed on 1 July 1916. Scott is likely ‘Locky’ of ‘Covenant’.

Above: Although stating '18th' battalion, this is the Pension Record Card for Walter Scott of the 12th (Sheffield City) Battalion Y&L Regiment

We can track Roddy’s experiences through his two small pocket diaries – whose transcription is held by the York & Lancaster Regiment Archives, Rotherham. ‘Covenant’ spends many pages on the battalion’s initial training at ‘Blackmires’ (Redmires, on the moors on the western edge of Sheffield). Roddy’s diary begins on 31 December 1914: ‘Had a good night in camp. Sang Old Lang Syne for the officers at Redmires’. Like many soldiers prior to active service, he married his sweetheart, Mabel Witheford, on 13 May 1915 – on 28 April he wrote: ‘Saw the Colonel. Got permission for marriage.’ ‘Covenant’ leaves Mark Fenner perhaps regretful that he had not proposed to his ladyfriend, Helen, prior to the battalion leaving for Suez. Joy was followed by sorrow for Roddy. When the unit moved to Salisbury Plain, his mother fell ill and died. He fretted for two days before being given permission to return home. Just prior to departure, the unit was sent to Larkhill for its musketry course – ‘the most miserable camp we have struck so far’, Roddy complained.

Egypt

The unit was first sent to Egypt, departing on SS Nestor on 21 December 1915. Roddy recorded: ‘Set sail from Devonport at 11.30 am under escort of 2 gunboats who left us at 10 pm’ – an uneventful voyage, the major excitement one day out was fellow reporter Scott losing his cap overboard whilst on submarine guard. On Christmas Eve all ‘were singing Xmas carols for hours after turning in. Rather a jolly time’. The singing was repeated on New Year’s Eve, on which day Roddy ‘sighted a boat being chased by a submarine’. They arrived at Port Said on 2 January. ‘Covenant’ devotes only six pages to Egypt, implying general boredom. Sent to the Tineh Pass, Roddy described hot days, windy and dusty, but freezing nights.

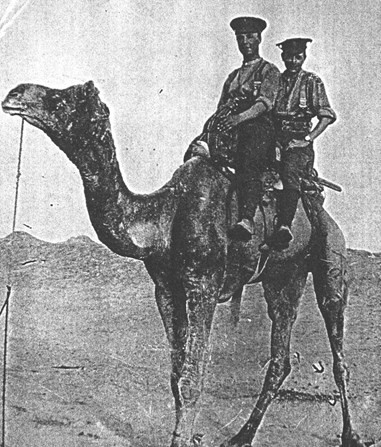

Amidst guard duty, rowing across the canal, fatigues and putting in telegraph poles, Roddy was lucky enough to be taken up by Second-Lieutenant A. J. Beal (killed on 1 July 1916). Another camera enthusiast, Beal first had Roddy developing films, then acting as assistant in the field. On 1 March he was ‘Out with Mr Beal and the camera. We took the prisoners, then the flying machine, mosque, and Indian transport’. The following day Roddy had the precious camera himself: ‘I took a group of the tent boys, also the SBs. Also took a group near the camels.’ He and Scott rode a camel themselves that day. Neither would have envisaged the possibility that exactly four months later Scott would be dead and Roddy out of the war. Eight days later they set sail for their ‘covenant with death’ on the Somme.

Roddy & Scott – 2 March 1916

France

Roddy found the marching to the Somme hard – on 27 March he described ‘a 13 mile march to Vignacourt, a most cruel march,’; and the following day a similar 14 mile march to Beauquesnes – “Took me all my time to stick it’. ‘Covenant’ describes these ordeals for Mark Fenner in detail. Roddy went into the front line on the Somme for the first time on the night of 1/2 April – ‘Burnt all my letters before leaving’. Fen describes his kit ‘down to the essentials, even dumping my spare shirt and socks’. Roddy noted ‘a bad strafing do at 6.30 to 7’, Fen describing how ‘the racket was tremendous’. On the 4th Roddy wrote: ‘Rat Street all day on sentry. At tea time I was making tea when a shell came & just about buried me and the fire”. Fen describes how ‘the mortar exploded on the parapet behind me’ and ‘flung me the rest of the way round the corner’.

On 30 April, Roddy ‘received my stripe, Lance-Corporal unpaid’. Fen is given two stripes at this point (and soon advanced to Lance-Sergeant). On 5 May Roddy was opening up some old French trenches, and recorded how: ‘We even dug up bodies of French soldiers’. Fen, on the same task, describes how ‘the French had left indications of their indifference about in the corpses that were buried too near the surface’.

Although Harris appears to follow Roddy’s diary (to which he must have had access), closely at this point, much of Roddy’s time was spent labouring. Harris, as fiction writer, makes life more exciting for Fen with a trench raid, and even a spell of (improbable) home leave. The reality for Roddy was more mundane – fatigue after fatigue, not to mention three periods of several days illness, which Fen is never burdened with. Roddy, like Fen, was not spared the death of comrades. On 26 May he recorded: ‘On working party in Rob Roy. When we got working the Germans turned their machine-guns on us & killed F. Walker and wounded Ed Robinson, then the Germans shelled us off the top. An awful night’. Walker was a Sheffield fish and poultry dealer; Robinson would be killed on 1 July.

1 July 1916 - Serre

Roddy went into the trenches in Matthew Copse on 15 June. Between then and 1 July, much of his life comprised fatigues once more – Harris clearly recognised that such did not match the climax to his novel. Like Roddy, Mark Fenner was in D Company. Whereas Fen makes it into the German front line at Serre, Roddy’s experience was the following: ‘Stood in assembly trenches from 3.15 under very heavy bombardment until 7.29 when the great advance commenced. I only went 300 yards when I got hit in foot & head, so made my way back which took me 6 hours to get back to Staff Copse, where I got my wounds dressed. Had a sleep then made my way back to Euston Dump. Arrived there at 11 p.m.’ D Company (with B) were in the third & fourth waves.

Gibson & Oldfield, in ‘Sheffield City Battalion’, note that ‘Because Rob Roy had been destroyed, these two waves had begun their advance much further back than originally planned. The fourth wave had 500 yards to go even before it crossed the British front line’, having at least 4 trenches to cross. If Roddy’s estimate of 300 yards is correct, it is very likely that he was wounded behind the British front line, Gibson & Oldfield describing 50% casualties before this geographic point. The unit’s casualty rate was 66%, with 513 dead, wounded or missing, and a further 75 slightly wounded. From ‘D’ Company, 16 were killed in action, 7 died of wounds, 56 were wounded and 42 were missing. Whether anyone came back from the German front line to give Harris his account of the fighting there is unknown.

Hospitalisation

Roddy arrived in Manchester on 6 July, sent to Nell Lane Military Hospital, West Didsbury. His wife visited two days later when he was still in bed.

Above: Nell Lane Military Hospital today.

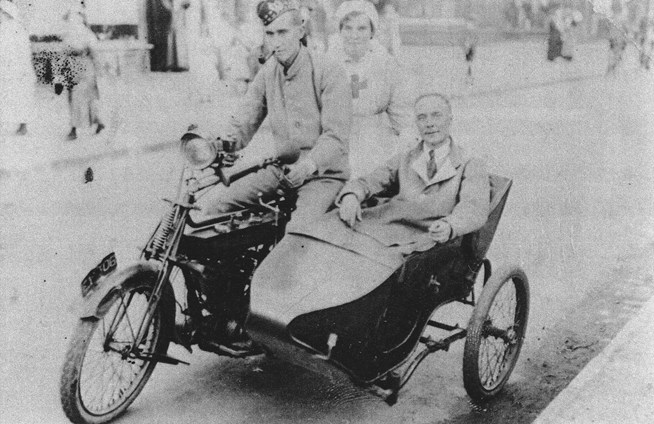

It was the 24th before he ventured out: ‘Out of hospital by 2.30. Went with the two Miss McWilliams for a row on the lake in Platts Park. Had tea out & returned to hospital at 8.45.’ On the 8th of August he was sent to Paddock House, Osbaldthistle, a convalescent hospital, but by 4 September was back in barracks at Pontefract. On 22 September 1916, after three medical boards, he was discharged from the Army.

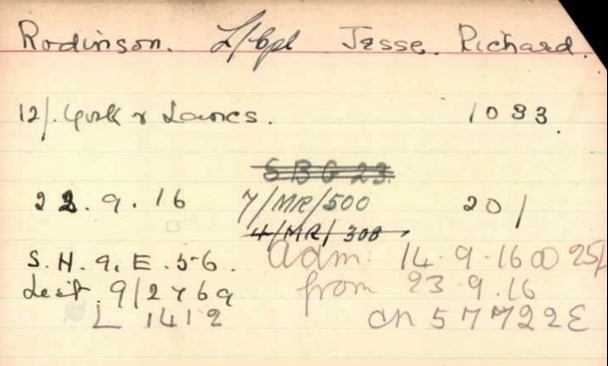

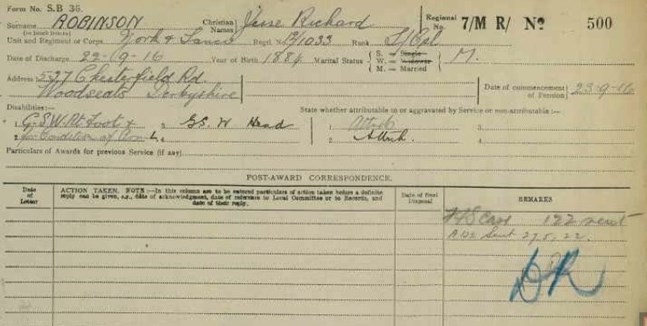

Above: The Pension Card and Ledger showing his wounds (the ledger mis-spells his name as Robinson but his regimental number is correctly detailed.

A life beyond the City Battalion

Roddy’s Western Front war may not have been quite as exciting as Mark Fenner’s, but John Harris had to drive his novel towards its dramatic climax. Unlike Roddy, Fen emerges from the Serre maelstrom uninjured – like Roddy, a number of his friends are dead. Following discharge, Roddy returned to photography for the Sheffield Telegraph, thus encountering John Harris. He was, allegedly, the first photographer to use a wide-angle lens to cover a football match. He died in 1974, his wife Mabel having died in 1969. The couple had one daughter. A sight problem meant that she was never able to read her father’s minutely written diaries. The ability to enlarge the font of the writer’s transcription meant that, at the age of 94, she could read her father’s account of his service for the first time.

Peter Hodgkinson is the author of a number of books on the First World War, and lived in Sheffield for 20 years. It was in Tunbridge Wells that he met Alistair Caisley, a solicitor, who, as Roddy’s great-nephew, held his diaries. The photographs are within his copyright. On 1 July 2016 Alastair was at Thiepval, and described Roddy’s experiences of exactly 100 years before on the BBC1 coverage of the centenary that day.