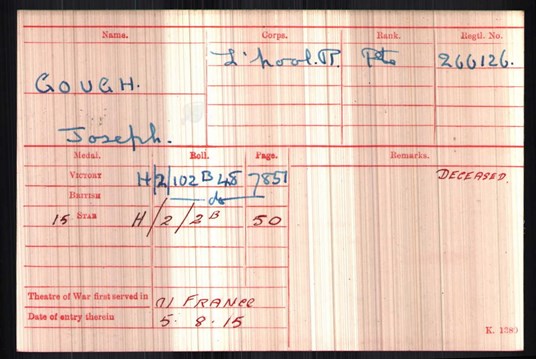

A Liverpool Lad at Ypres Pte Joseph Gough KIA 31 July 1917

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Liverpool Lad at Ypres Pte Joseph Gough KIA 31 July 1917

“The Valley of the Shadow, 31 July 1917.

Down in the valley the Steenbeek flows, A brook you may cross with an easy stride,

In death’s own valley between the rows of stunted willows om either side.

You may cross in the sunshine without a care, with a brow that is fanned by the summer’s breath,

Though you cross with a laugh, yet pause with a prayer, for this is the Vale of the Shadow of death.

Major E.G.Hoare. O.C. 9 King’s (Liverpool) Battalion during the operation.

Joseph Gough (photo below) was born in 1898, the second eldest of five sons of Matthew and Elizabeth Gough of 33 Helena Street, Walton.

Above: the family home in Walton.

A devout family, the children attended the St. Francis de Sales Church and Catholic Junior School. Unfortunately, Matthew Gough died in 1905 leaving Elizabeth a widow with five children to bring up, so she took in ironing to make ends meet, and later worked in the laundry at Walton hospital.

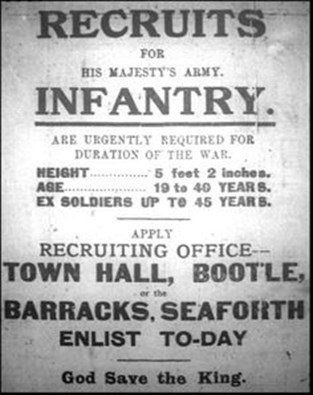

Before war was declared in 1914, William the eldest son (age 19) enlisted in the Territorial Forces on 4 March and was posted to the 1/7 King’s (Liverpool) Regiment as Pte. 1915 Gough. In August of that year recruiting posters soon appeared, and it may well have been the one pictured that Joseph saw before enlisting in Bootle.

Above: Bootle Enlistment poster

As soon as they left school the two eldest boys William and Joseph had found work locally. William as a florist’s errand boy and Joseph in the Union Cold Storage Co. in Williamson Square. These incomes were vital in helping to support the family and their widowed mother.

Above: Joseph’s workplace

However, both brothers left their civilian employment once war was declared and Joseph followed in his brother’s footsteps enlisting at 99 Park Street, Bootle at the Drill Hall of the 1/7 King’s who were part of Liverpool Brigade, West Lancashire Division.

Above: King’s Liverpool cap badge

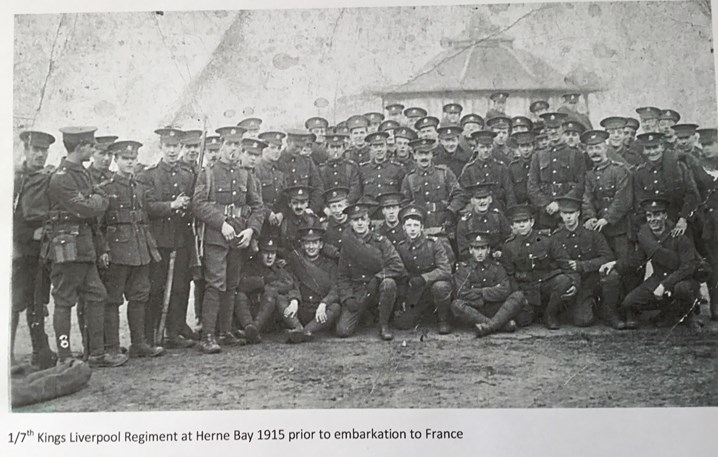

In March 1915 the battalion landed at Le Havre and transferred to 6 Brigade, 2 Division, and William’s Medal index card shows he was amongst the men who arrived on the 7 March. Prior to this they were in camp near Canterbury, but had some leisure time between parades and route marches to visit nearby seaside towns, as shown in the next picture.

Above: Men of the 1/7 Battalion at Herne Bay prior to departure for France

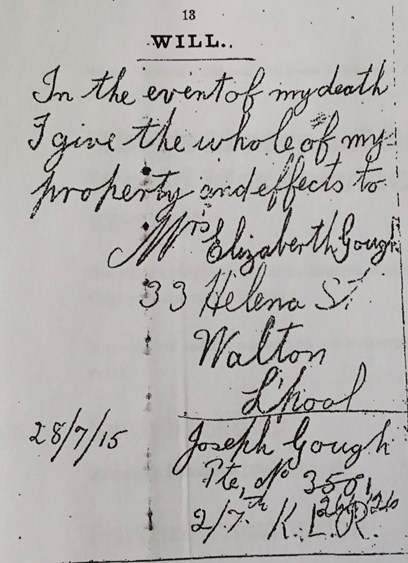

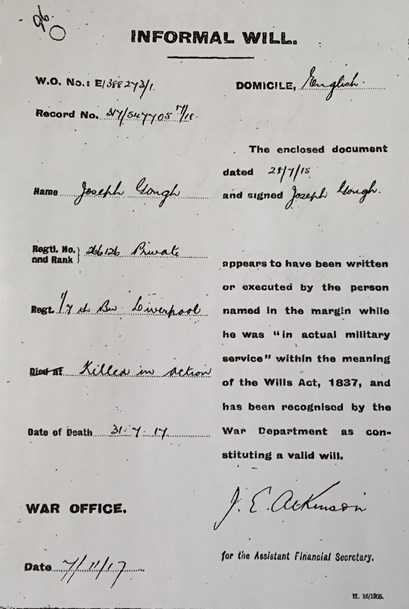

In every soldiers’s pay book, AB64, there was a page on which he could make his Will which would be extracted in the event of his death and sent to the War Office. We have an example of this with Joseph’s Will and the accompanying War Office form shown in the next two photos.

Before telling Joseph’s story in full, it is worth mentioning what happened to his elder brother William. Having landed in France in March 1915, the battalion were sent to the Bethune area where they remained for the rest of that year. They moved in and out of the line at Annequin, Noeux-les-Mines, Cuinchy and Essars, and the War Diary gives an insight into the conditions they experienced. After a dry summer, the trenches quickly deteriorated and became a morass in places. The Adjutant noted on 12 November 1915 – “Trenches waterlogged”. The following day he states – “ Trench waders proved a boon to everyone.” A timely arrival of some vital kit.

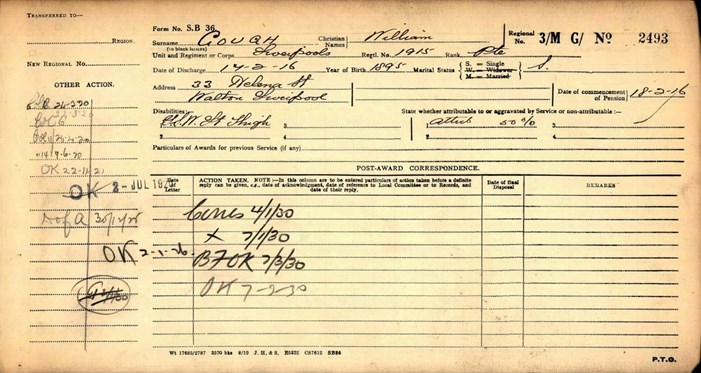

February 1916 saw the battalion move out of the Bethune sector to relieve the French 81 régiment d'infanterie at Marboeuf, south west of Arras, on 16 February. A day later the entry in the War Diary states – “Nothing unusual in Front Line. 3 men wounded accidentally by a box of bombs exploding” One of these men was William Gough. He was awarded a 50% War Pension for a wound to his left thigh, and was invalided out of the Army receiving a Silver War badge number 99456. He continued to live in Liverpool until his death in 1966 age 71.

Above: William Gough’s Pension Ledger

Joseph Gough arrived in France on 5 August 1915,served alongside his brother for six months, and had twenty one months in total of service overseas. Billeted in Essars, the Battalion underwent a constant programme of training, and provided working parties at Pont Fixe, Windy Corner and Cambrin. The following month saw 108 NCO’s and men attached to 176 Company, Royal Engineers for mining purposes. They were employed at Orchard Trench/Redoubt and Duck’s Bill mines, and undoubtedly a bathing parade and change of underclothing was welcomed at that stage. Additional working parties were also found for Moat House Redoubt and the Lavender Lane Sidings.

On the 24 September the battalion took up position in the trenches and several working parties were detached to other battalions. On the following day the 1/7 King’s took part in operations covering the left flank of 5th Brigade, and this was the first time Joseph would have experienced actual combat. Until they left the trenches in early October the King’s suffered very light casualties, and continued to provide working parties day and night on wiring, carrying, and burial duties.

The War Diary shows a rather routine month for October and November 1915, with mention of “Baths for men” on 24 at the Collège des Jeunes Filles in Bethune, which has only just recently been demolished. On moving to Beuvry, four officers and 110 men were attached to the 180th Mining Coy. R.E., and further parties of up to 300 men went to Cambrin. Additionally, motor buses were used to move 150 men to work on trenches at Windy Corner.

In December the Battalion entrained at Lillers for Saleux ,near Amiens, where they went into billets at Briquemesnil. The War Diary indicates they were only in that area for a short time with the following entries:-

“7th -Battalion cleaning up their Billets.

8th - “ “ “ “ “ and also the Village.”

Was this an effort to keep the entente cordiale, or perhaps the place required a makeover?

January 1916 saw the 1/7 King’s training at in the Warlus area, with new drafts arriving from England. Mention is made of firing on Ranges, and in February they were inspected by Lord Derby. It was during this month that William Gough was injured, and evacuated back home. Weather conditions in early 1916 were extremely bad in the Arras area, and the men experienced bitter cold with a lot of snow.

Above: 1/7 King’s in a communication trench, summer 1916, a marked contrast to earlier that year.

The War Diary for March to June 1916 is missing, but on the 1 July at the start of the Somme fighting the King’s were in bivouacs near Fricourt. The months of training, drills, and sheer hard work were shortly to be tested when they spent five days in the notorious front line trenches at Guillemont in August. From their position in support trenches at Tailles Bois the 1/7 moved up the relieve the 1/5 King’s on the night of 8 August. However, the attack floundered through poor organization, and a special report outlining the circumstances was sent to H.Q. 165 Infantry Brigade. An excerpt speaks volumes about the failures involved.

“A” Company, owing to the uncertainty of the guides, and the fact that the trench they were supposed to jump off from did not exist, as shewn on the map, found themselves at Zero in the open, without any idea of where their objective was, and dug themselves in a shallow half-dug trench about 100 yards to the rear of Shute Trench, and as it afterwards turned out, almost opposite their objective. “B” Company (in which Joseph served), misled by their guides, got to their position just at Zero, which position had to be reached over the open. They were completely out of touch with the right attacking Company (A). They were seen by the enemy and suffered some casualties getting there. “C” Company and Bombers attempted to attain their objective but owing to a lack of accurate knowledge of the ground and the position of the enemy were repulsed. “D” Company were in reserve.

During the morning of the 9th we obtained touch with all Companies but “B”, who were in a strong position in front and no Communication Trench back. During the day all positions were consolidated.

On the night of the 9th “A” Company commenced to join up to Shute’s Trench. “B” Company sent out a party for water, but this party owing to the loss of direction, failed to get back to their Company. An attempt was made to relieve a Machine Gun which was in the vicinity of “B” as the Gun was without water and ammunition. This also failed for the same reason. During the night our Barrier was heavily shelled and for a short period the best part of the Garrison were withdrawn into adjoining trenches until the shelling finished, when they returned to the Barrier and commenced repairing the damage done.

One the morning of the 10th Capt. Owens and the Machine Gun were relieved.

One the same night (10/11th) “A” Company assisted by half a Company of Pioneers, dug a trench across to “B” Company, which was completed on the following night. On the same night “B” Company were revictualled, but received no water till the following night.”

To compound this situation friendly fire by our Artillery caused casualties, as noted by Col. Shute of 1/5th King’s who wrote, “ there was much confusion as to the locality of our troops”. “B” Company were actually cut off for two days, and their true position only found with the help of an aerial photograph and a magnifying glass. A post-action report after Guillemont by Gen. Sir Hugh Jeudwine, emphasized the need for accurate maps and operational orders to be available down to NCO level, trenches properly located with clear notice boards, and the importance of reconnaissance and clear communications.

September 1916 found the 1/7 King’s manning trenches in the Delville Wood – High Wood sector, and on 25 September they attacked and gained Sunken Road and Factory Corner at Guedecourt. Over five days they lost 43 killed, 197 wounded, 3 wounded-shell shock, and 21 men missing. However, their actions on the Somme helped establish a thorough understanding of what was required for a successful attack.

The period October to December saw the 1/7 moving to Brandhoek by rail and road before going into support at Ypres. When out of the line they provided cable burying parties, then relieved the 1/9 King’s, but overall it was a very quiet time for them. Unfortunately, they did not have their Christmas dinner until the 1st. January 1917, and then moved to Proven, assisting Royal Engineers with railway construction all month. Between February and April more training alternated with manning the left sub-sector support trenches at Railway Wood.

On 5 May they were in the line when a camouflet was blown at 4.20am by the enemy. The same day one of the officers was killed by a German sniper, but the War Diary records very few casualties at that time. On the 18th. May the 1/7 King’s were relieved by the 10th.Liverpool Scottish and were moved by rail to Poperinghe and were billeted in the Hopstore. After another rail journey to Watten, more training extending into the middle of June took place before they arrived at Derby Camp.

As the time grew closer to the opening of Third Ypres, most of July was spent at the Ranges and battle practice area at Moringhem, east of St. Omer.. The War Diary of the 1/9 King’s who were also there at that time gives an idea of events:-

During our stay in this village "practice in the attack" was carried out under Brigade arrangements, each Battn operating on the front that was to be allotted to it in the attack. A Special Training Area was allotted to the Brigade for the Practice Attacks, this area being marked clearly with Tape & Notice Boards, indicating the objectives that the Brigade would be allotted during the actual attack. These practices were very instructive, and practically every man in the Battnwas fully acquainted with the Area, and with what would be expected of him, during the actual "show". The whole Battn was very keen and in very high spirits as to the "show" being a huge success

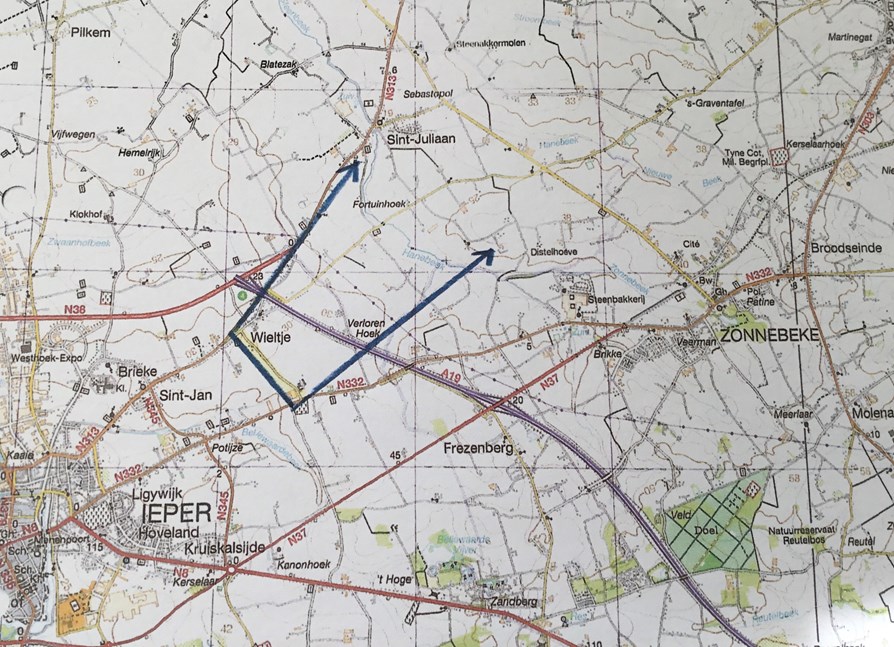

On 26 July, 1/7 King’s manned trenches in the Potijze sector for three days, before moving into assembly positions for the upcoming operations.

Above: Map of area between blue lines over which 1/7 King’s advanced.

Operations Order number 93 issued by the C.O 1/7 King’s on 26 July, Lt.Col. C.K. Potter, ran to six foolscap pages outlining their part in the attack on the Frezenberg Line through Pommern Redoubt ending in the consolidation of the Black Line towards St. Julien.B Coy. had map references D.19a.60.02 to D19a.45.40 as their first objective, then advancing to get in touch with D Coy. Reading through the order illustrates that every attack aspect was covered thoroughly, but some of the appendices show in contrast the “housekeeping” side of things.

“Appendix 3.

Water, Tea etc. The extra water bottle filled with Tea on X Day will be carried in the Pack.

Breakfast will be made in the Y Day area late in the evening and carried up in Thermos cans.

Water to fill No. 1 Water Bottle will be supplied from the Water Cart on Y Day and night.

The Quartermaster will send Cocoa up with Y Day Rations

The attention of all ranks is drawn to the necessity of returning Empty Petrol Tins; unless this is done the supply of water cannot be guaranteed.”

The Q.M.’s cocoa sounds more appealing than petrol tasting water.

On the night of 30 July troops were instructed to move in sections at 50 yards distance , with all movement east of Junction Road, (today’s Zonnebeeksweg N332) to be completed by 9.30pm.Joseph’s “B” Company had been billeted in the Ramparts at Ypres, so had to file past the Battalion dump at Potijze on their way to Oxford Road assembly point, deposit surplus kit and collect any stores to be carried, ensuring that they crossed Junction Road at 8.15pm.

Above: The junction of Wieltjestraat and Zonnebeekseweg, site of Oxford Road and Warwick Trenches where B Company waited on the night of 30 July 1917.

Once the attack commenced the Battalion had to leave Warwick and Oxford trenches in order to pass over the Blue line at Zero plus 1 hour 15 minutes, and B Coy. formed the third and fourth waves on the left. In lessons learned from the Somme, men had to move in lines at twenty paces distant, with waves moving at one hundred yards apart. At 2.30am. hot cocoa and rum was served, then at Zero plus thirty minutes i.e. 4:20am.the Battalion left the assembly trenches.

Above: A map showing German strongpoints 31 July 1917

For the first phase of the battle H.Q. was at Warwick Farm, where a rebuilt farm stands today. As the day progressed H.Q. moved subsequently to Uhlan Farm and finally to Pommern Farm. Preparation notes stated that six tanks were to be made available, but heavy rain and churned up ground from artillery fire made their effectiveness questionable. As the attack commenced troops were instructed not to wait for tank support. The narrative of operations clearly gives a picture of B Coy’s part in the action.

“On the left, B Coy., after passing through heavy shell and MG fire, crossed the Hanebeke by bridges, and entered Pommern Castle on either flank at 06:06am. Pigeon message was sent off at once. The dugouts and trenches were mopped up and connection obtained with 9th King’s on left and 15 Division on right, who were some way back to the right rear. A party under 2nd Lt. Leach was pushed out to construct a strong point on Hill 35, and came under severe MG fire. The strong point was established on the N.W. side of the ridge. A light field gun was captured en route to the positions on Hill 35 and enemy were caught by Lewis Gun fire when retiring.

The remainder of B Coy. proceeded to consolidate the position in Pommern Castle, Capt. Heaton taking up his main position on the West side of the castle. When A Coy arrived followed by D Coy., he took command of the whole force and was untiring in the work of strengthening and consolidating the position. Two supporting posts were pushed out about 150 yards East of main defensive position and occupied at night. By day, an advanced post was maintained at S.E. point of Pommern Castle with telephonic communication to main trench.”

Capt. Heaton’s actions at this stage demonstrated good local decision making, but casualties had been heavy and reserve stretcher bearers had to be sent for. Some 400 men from other units were utilised, with eight men per stretcher necessary at times. The weather conditions had deteriorated making trenches impassable in places, and bearers were forced to carry in the open picking their way round shell holes. B Coy. had consolidated their objective at the Pommern trench system, but at a proportionally higher rate of casualties that the other Companies. No firm evidence is held as to where Joseph was killed, but the Pommern area saw the fiercest German responses.

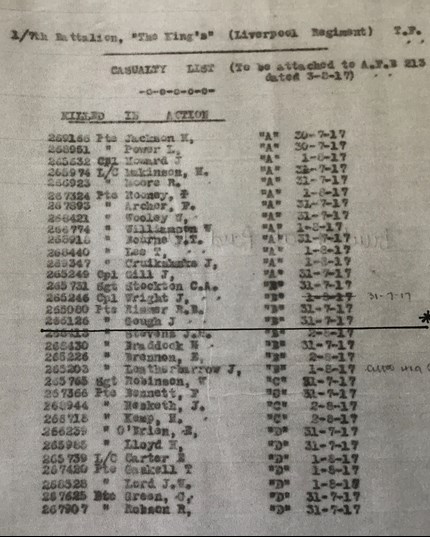

The War Diary gives a full list of Battalion casualties, with 32 killed in action, 137 wounded and 23 missing on 31 July.

Above: Casualty list showing Joseph’s name.

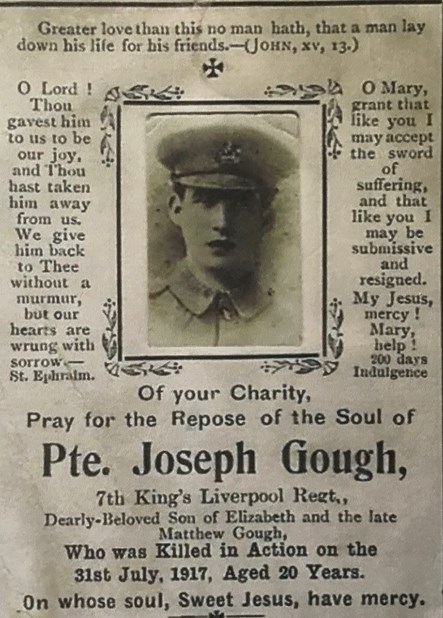

The 1/7 King’s had met and held their objectives, and it was said the 31 July was the Battalion’s finest hour. They held the position taken until 3 August when they were relieved by a battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers. Newspapers in the Liverpool area published headlines praising the actions of “ Local Troops which would be read about with considerable pride and interest “. However, the Liverpool Echo of 17 August 1917 carried the following article:- “ Walton Private killed. Mrs. Gough of 33 Helena Street, Walton has received official notice of her second son, Private Joseph Gough, the King’s Liverpool Regiment. He was killed in action on July 31. He was in his 20th. Year. Before joining the Army he was in the employment of the Union Cold Storage engine department in Williamson Square.”

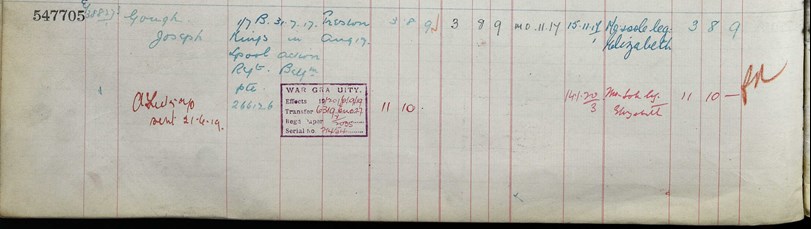

Above: Joseph’s effects shown in the Army register

Above: Joseph’s Medal Index card.

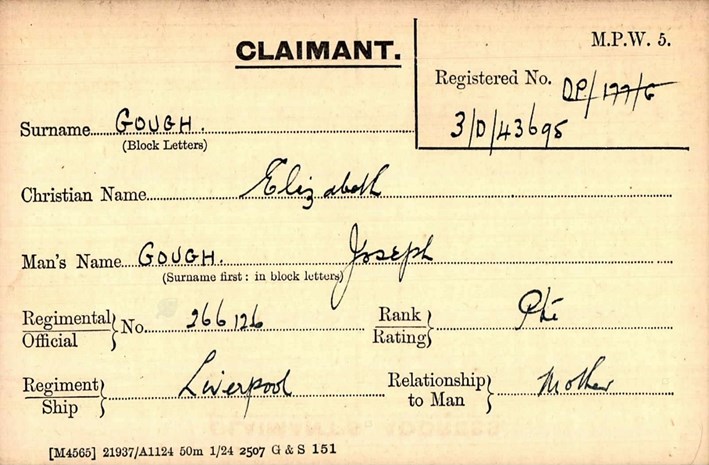

Above: Joseph’s Pension card

Above: Joseph’s Memorial card

Joseph’s family have never forgotten him, and were keen to find out more about his Army service with the 1/7 King’s Liverpool Regiment. They had never been to see where he fought, and only knew he was commemorated on the Menin Gate. Like so many others, the nature of the fighting and the terrain prevented many bodies being recovered in the Ypres area. The 1/7 King’s Liverpool are commemorated on panels 4 and 6, and Joseph’s name is engraved at the very top of panel 6. This on the immediate right hand side as you enter from the town. A scheduled trip to Ypres provided the opportunity to cover the ground fought over on 31 July specific to Joseph’s regiment, and give a copy of the research to his great-niece. This was taken on a visit back in Liverpool and shared with Joseph’s family there.

Above: Last Post Ceremony, Menin Gate

Above: A poppy for Joseph

Article by Dora Ringland