Battle of the Falklands 1914

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Battle of the Falklands 1914

“We landed to bury our dead. The dignified memorial service in Port Stanley Cathedral, and the sight of four boy buglers of Invincible, with tears streaming down their cheeks, blowing the Last Post over the graves of their comrades, are imperishable memories.”

Thus wrote Lloyd Hirst who, as Assistant Paymaster in HMS Glasgow, was one of the officers who both witnessed the sinking of Rear Admiral Cradock’s cruisers, HMS Good Hope and HMS Monmouth, off Coronel on 1 November 1914 and was involved in the destruction of Cradock’s nemesis, Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee’s East Asiatic Squadron, on 8 December 1914 off the Falkland Islands.

The Admiralty acted quickly to avenge Cradock’s defeat, to restore the Royal Navy’s prestige and to protect the trade routes. The instruction was clear: “... essential recover control. First Sea Lord requires Invincible and Inflexible for this purpose”, read the telegram to Jellicoe on 5 November, “Sturdee goes C.-in-C. South Atlantic and Pacific”.

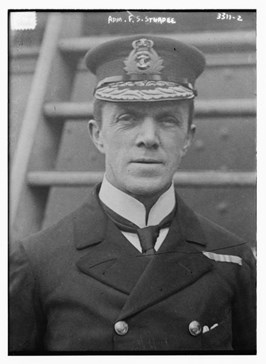

Above: Vice Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee

Vice Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee’s force, which arrived at the Falkland Islands on 7 December, comprised the battle cruisers Invincible and Inflexible, the armoured cruisers Carnarvon, Cornwall and Kent and the light cruisers Bristol and Glasgow. It was the speed and the 12-inch guns of the battle cruisers which made this force deadly to von Spee’s two armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and three light cruisers Dresden, Leipzig and Nurnberg.

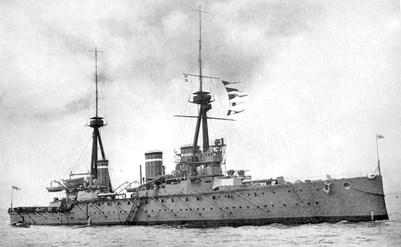

HMS Invincible – Vice Admiral Sturdee’s flagship

SMS Scharnhorst – Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee’s flagship

On 7 December Sturdee did not know the whereabouts of the Germans and there was the prospect of having to round the Horn in search of them with every chance of missing them amongst the islands and inlets of the west coast. Uncertainty about von Spee’s location was swept away on the morning of 8 December by a signal from the Sapper Hill observation post reporting the approach of two men o’ war. The danger for Sturdee’s ships was that they might be caught coaling in the confines of the harbour, without room to exploit the range and power of their 12-inch guns, but that danger was averted when, at 9.19 a. m., the old battleship Canopus, grounded to improve her gunnery and directed by an observation station ashore, opened fire with two salvoes from her 12-inch guns. Not expecting such a reception the Germans turned away and the chase began. Only bad weather to the south could save von Spee but 8 December was an unusually fine day with a calm sea.

'Invincible and Inflexible steaming out of Port Stanley in Chase'- the start of the Battle of the Falkland Islands, 8 December 1914. (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird Collection)

Sturdee’s squadron proceeded to sea at 10 a.m. and just before 1 p.m. the battle cruisers opened fire at the nearest targets, two light cruisers, at about 16,000 yards. At about 1.20 p.m. the battle cruisers engaged the German armoured cruisers and Inflexible noted two hits at between 14,000 and 12,000 yards. Invincible received her first hit from a German shell at 1.45 p.m.

At about 2 p.m. the range increased, the firing ceased and the Germans made off to the south in search of bad weather. After another chase the battle cruisers opened fire again at ranges from 16,000 to 12,000 yards and this part of the action continued for about an hour.

Battle of the Falkland Islands, 1914 by William Lionel Wyllie

Soon after 4 p.m. Scharnhorst, listing heavily and on fire, sank. The battle cruisers shifted fire to Gneisenau at 14,000 to 10,000 yards. Funnel smoke from the battle cruisers and Gneisenau’s irregular course made shooting difficult for the battle cruisers but between 4.45 p.m. and 5.30 p.m. Gneisenau was seen to be hit many times and at about 6 p.m. she heeled over and sank. Captain Beamish, of Invincible, recorded that a total of 108 officers and men were picked up, of whom fourteen died and were buried the next day.

Sturdee’s slowest ship, Carnarvon, had watched the battle cruisers race ahead and engage von Spee but just before Scharnhorst succumbed Carnarvon was close enough to open fire on her. At 4.44 p.m. Carnarvon opened fire at Gneisenau and continued in action for about an hour.

On the British battle cruisers there was just one fatal casualty. Inflexible’s log records: “Departed this life:- Neil Livingstone AB. RFR. Killed in Action”.

Neil Livingstone, one of the crew of the 4-inch guns, was sheltering behind X turret when the main derrick was struck by an 8.2-inch shell from the Scharnhorst. Either a piece of that shell or a piece of the derrick struck him a huge blow in the centre of his back and drove in the spinal column probably puncturing an aorta, according to Inflexible’s Fleet Surgeon. Livingstone was carried below but soon afterwards expired. He was buried at sea.

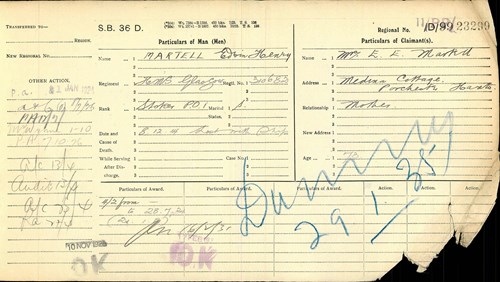

When the German light cruisers separated from von Spee Cornwall increased speed to 22¾ knots and, in company with Glasgow, gave chase to Leipzig. Glasgow engaged Leipzig at about 3 p.m. with six-inch gunfire and about an hour later was able to open fire with her 4-inch guns. Each time Leipzig turned to bring her broadside to bear on her pursuers she lost a little of her lead and gradually Cornwall was able to overhaul her and, at 4.17 p.m., bring her battery of nine six-inch guns into action at 10,500 yards. Observers on Cornwall saw Leipzig on fire fore and aft and at 7.16 p.m. Cornwall ceased fire. Because Leipzig had not struck her colours and because of the fear that she might launch torpedoes Glasgow and Cornwall opened fire again at 7.55 p.m. and finally ceased at 8.11 p.m. From 9 p.m., for over an hour, boats from both ships searched for survivors. There were eighteen. Leipzig sank at 9.23 p.m. Cornwall suffered no casualties in the action. Glasgow’s log recorded the loss of Edwin Martell “killed in action”. Martell received a fatal head wound. He was standing at the foot of the foremast when a 4.1-inch shell exploded against the mast just below the foretop.

Above: The Pension Ledger of Martell, from the WFA's Pension Record Archive

Glasgow also suffered seven wounded, one dangerously so. The latter, Maurice Bridger, died at Lisbon from meningitis on 27 January 1915 and was buried at sea that day. He was on board S.S. Orita whilst on passage home.

Kent had no fast light cruiser to help her chase Nurnberg. Success was accomplished partly by the strenuous efforts of her engine room staff in raising her speed to 25 knots and partly by the bursting of two of Nurnberg’s boilers. Once under the guns of Kent there was little hope for the unarmoured Nurnberg, although she did hit Kent thirty-eight times as the range decreased from 11,000 yards to 3,000 yards. One of those hits nearly caused the destruction of Kent. A 4.1 inch shell entered one of Kent’s 6-inch casemates setting fire to charges. In the words of Surgeon Thomas Dixon “Sergeant Mayes did an act here which I hope will get him the V.C.”. Mayes threw the flaming charge away from others in the passage and closed the watertight doors. In this way he saved a severe fire and explosion which might have led to the destruction of Kent. He was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. At 6.36 p.m. Kent ceased fire. Another shell from Nurnberg caused Kent to open fire again nine minutes later and, as there was no further response from Nurnberg, to finally cease fire at 6.57 p. m. Nurnberg sank at 7.25 p.m. Kent’s boats picked up eleven men, of whom four died of exposure. Kent’s casualties, mostly from the casemate fire, were the heaviest of any British ship in this action. Kent’s Fleet Surgeon recorded the fate of his eight shipmates who were killed in action or died later of their wounds.

“HMS Kent – A3 Casemate”

Samuel Kelly was in the stoker’s bath room at about 6 p.m. when a 4.1-inch shell, which failed to explode, penetrated Kent’s side and shot both his legs away below the knees. He fell, sustaining a scalp wound. He died of shock at 9 p.m. that night.

Walter Kind was in A3 casemate. He suffered severe burns. Once his burns had been dressed he was able to take some beef tea and brandy. However, he succumbed to his injuries at about 3 p.m. on 9 December.

Arthur Titheridge, a gunlayer in A3 casemate, suffered severe burns. Dressings were applied and morphia administered but he died from extreme shock at 11.40 p.m. that night.

Walter Wood, a cartridge handler in A3 casemate, was killed in the casemate fire. He was found with elbows flexed and hands facing inwards as if he had been carrying a cartridge. Fleet Surgeon Edward Pickthorn surmised that Wood had been killed by lyddite fumes.

Walter Young, one of the Boatswain’s rigging party, was wounded in the back, at about 5.50 p.m., by a large splinter of metal. After initial treatment he was taken to the Sick Bay where he died of shock at about 9.30 p.m.

George Duckett, one of the ambulance party in A3 casemate, was badly burned. He made his own way to the sick bay where his wounds were dressed more than once and morphia administered. He took some beef tea and brandy, and survived until 9.55 p.m. on 9 December.

George Snow suffered severe burns in A3 casemate but he appeared to make progress as a result of treatment and was transferred to Port Stanley hospital on 13 December where he died of his injuries on 20 December.

Tom Spence was badly burned in A3 casemate. After treatment he appeared to have partially recovered from the shock and was transferred to the hospital at Port Stanley. However, he died there on Christmas Eve, 1914.

The supply ships which accompanied von Spee’s force at some distance were sunk, with no loss of life on either side, by the light cruiser Bristol and the armed merchant cruiser Macedonia.

By the time Leipzig had been dealt with, Dresden, faster than her consorts, had disappeared into the bad weather which was beginning to appear on the southern horizon. There was no chance that day of even the swift Glasgow catching her.

“Thus in a summary and complete manner”, wrote Assistant Paymaster Lloyd Hirst, “was Coronel avenged”.

The 1914 Battle of the Falkland Islands Memorial

Article by David Seymour